Ketupat

Unopened bunch of cooked ketupat on a plate. | |

| Course | Main course |

|---|---|

| Place of origin | Maritime Southeast Asia[1][2][3][4][5] |

| Region or state | Java,[6] Sumatra,[7] Malay Peninsula,[8] Borneo,[9] Sulawesi,[10] Bali[11] |

| Serving temperature | Hot or room temperature |

| Main ingredients | Rice cooked inside of a pouch made from woven young palm leaves |

| 1 bowl of ketupat sayur has approximately 93[12] | |

Ketupat (Indonesian and Malay pronunciation: kəˈt̪upat̪̚) is a type of compressed rice cake commonly found across Maritime Southeast Asia, particularly in Indonesia, Malaysia, Brunei, Singapore, Timor-Leste and southern Thailand. It is traditionally made by filling a pouch woven from young palm leaves with rice, which is then boiled until the grains expand and form a firm, compact mass. Ketupat is typically served as an accompaniment to meat, vegetable or coconut milk-based dishes and is widely prepared for festive and ceremonial occasions. The dish is known by various regional names, including kupat (Javanese and Sundanese), tipat (Balinese), katupat (Banjar), katupa (Tetum), katupa’ (Makassarese), topat (Sasak) and katupek (Minangkabau), among others.[13]

Beyond its culinary function, ketupat holds deep symbolic and ritual significance in many communities across Southeast Asia. It is most closely associated with the Islamic celebration of Eid al-Fitr (known regionally as Lebaran or Hari Raya), during which it is often prepared in large quantities and shared among family, neighbours and guests. Beyond Islamic traditions, ketupat also appears in Balinese Hindu temple offerings, traditional healing practices and seasonal rites marking harvests and ancestral veneration. It plays a role in multiple belief systems, including Christianity and various indigenous spiritual practices.

Numerous regional variations of ketupat exist, differing in the type of rice used, wrapping materials, preparation methods and accompanying dishes. These include triangular ketupat palas, pandan-wrapped katupa' , alkaline-boiled ketupat landan and vegetable-filled ketupat jembut. Ketupat is also featured as a central ingredient in a variety of local dishes such as ketoprak, kupat tahu, ketupat sotong and ketupat kandangan.

History

Leaf-Wrapped Rice Traditions

The exact origin of ketupat is not clearly documented, and there is no definitive evidence identifying where or when the dish was first developed.[14] However, archaeological findings in Austronesian regions, including Taiwan, which is widely regarded as the ancestral homeland of Austronesian-speaking peoples, as well as the Philippines and various islands across Southeast Asia and the Pacific, have revealed Neolithic artefacts such as polished stone tools, decorated pottery and early agricultural implements. These discoveries are associated with the expansion of Austronesian culture, which included the spread of rice cultivation techniques and the use of tropical plants such as coconut and banana.[2]

Within this broader context, the practice of cooking rice wrapped in leaves appears to have deep roots in Austronesian societies. The widespread availability of coconut and palm leaves, along with the practical need for portable and self-contained meals, contributed to the development of leaf-wrapped rice cakes across the region. Ketupat is one example of this culinary tradition, which forms part of a shared cultural heritage that continues to influence food practices throughout maritime Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands.[2]

Epat and the Four-Sided Pouch: Linguistic and Regional Connections

The absence of physical archaeological evidence for early ketupat is partly due to its organic materials, which deteriorate easily over time. As a result, hypotheses about the origins of ketupat rely on indirect forms of evidence, including linguistic analysis, Austronesian material culture and regional culinary traditions found throughout Island Southeast Asia and the Pacific.[15]

Linguistic research indicates that speakers of Austronesian languages share vocabulary related to tropical plants such as coconut, banana and rice, which are central to traditional food preparation.[2][3] These lexical similarities are often associated with cooking and food-wrapping techniques using young coconut leaves, a method that underpins the preparation of ketupat and other rice cakes. This supports the idea that ketupat may have originated as part of a wider Austronesian culinary tradition.

In some Austronesian languages, the term kupat is thought to derive from epat, meaning "four", possibly in reference to the four-sided shape of the woven rice pouch. This linguistic connection suggests that the concept of wrapping rice in leaves may have developed across multiple regions or been shared through cultural exchange within the Austronesian-speaking world. The widespread use of similar terms and preparation methods reflects a common cultural heritage in which rice and leaf-wrapping hold both practical and symbolic importance.[4]

In the Philippines, leaf-wrapped rice cakes take several regional forms that reflect both cultural traditions and local ingredients. In the northern region of Ilocos, a variant known as patupat is prepared during the sugarcane harvest season. Classified as a type of suman, patupat is distinctive for its use of intricately woven palm leaf pouches filled with unsoaked glutinous rice (malagkit), which are simmered in freshly extracted sugarcane juice. Once cooked, the pouches are hung to drain over the cooking vessel. The sugar-rich liquid not only imparts a sweet flavour but also acts as a natural preservative, allowing patupat to be stored for several days.[16]

Further east, in the Mariana Islands, the Chamorro people prepare katupat, a diamond- or square-shaped rice pouch woven from coconut fronds and boiled until compact. Archaeological and linguistic evidence suggests that both rice cultivation and katupat production were established before Spanish colonisation in the seventeenth century.[17][18] Closely resembling ketupat, this tradition reflects the deep Austronesian roots of leaf-wrapped rice practices. Early Spanish records also highlight the craftsmanship of Chamorro women in weaving coconut leaves into both decorative and utilitarian items, including katupat containers.[19][20]

Beyond its role as food, katupat also holds ceremonial and symbolic significance. In Chamorro tradition, Laso Fu’a, a rock outcrop in Fouha Bay, is considered the cradle of creation for the people of the Mariana Islands, and in some accounts, for all of humankind. Chamorros have begun returning to this sacred site to offer prayers and gifts, including katupat, as a gesture of reverence and to ask permission to enter Guam.[18]

Ritual Feasting

Early written evidence of leaf-wrapped rice-based foods in Island Southeast Asia appears in the travel records of the Chinese Buddhist monk Yijing, who visited the Srivijaya realm in the seventh century. In his account of the “islands of the Southern Sea”, likely referring to parts of the Malay Archipelago, Yijing described monastic feasts during religious fast days in which hosts served rice and rice cakes on large plates made by sewing leaves together. These leaf plates were sometimes as wide as half a mat and could accommodate generous portions of food. Guests were served multiple types of dishes, with boiled rice and cakes often portioned in quantities large enough to satisfy several people, reflecting a strong tradition of communal dining.[21]

Yijing noted that these practices extended across both elite and common households, with offerings made to Buddhist monks in vessels made of bronze or sewn leaves, depending on social status. The widespread use of leaf-based containers and rice cakes in religious and communal settings reflects the longstanding role of leaf-wrapping and rice preparation in the region’s food culture.[22]

Kupatay, Kupat and Rice Rituals in Pre-Islamic Java

In ancient Java, the preparation of rice cakes wrapped in woven leaves held both cultural and ritual significance within pre-Islamic agricultural traditions.[14] Among Javanese communities, rice was not only a dietary staple but also a sacred symbol of life and prosperity, closely associated with the worship of Dewi Sri, the Javanese rice goddess of fertility and abundance. Leaf-wrapped rice offerings were likely used in rituals dedicated to Dewi Sri, expressing gratitude for successful harvests.[23][24] This practice reflects a broader pattern across Austronesian societies, where leaf-wrapped rice cakes served both practical and ceremonial purposes.

Although the term ketupat does not appear in early inscriptions, Old Javanese literary sources suggest the existence of related traditions. The Kakawin Ramayana, a Javanese epic poem composed in the 9th century during the Mataram Kingdom, contains a reference to a rice cake called kupatay, indicating the practice of wrapping rice in woven leaves was already established in Java. The term kupat also appears in later works, including the Kakawin Kresnayana (12th century, Kediri Kingdom), Kakawin Subadra Wiwaha and Kidung Sri Tanjung (14th to 15th century, Majapahit period). These references suggest that leaf-wrapped rice cakes were a longstanding element of Javanese culture prior to the widespread adoption of Hinduism, Buddhism and Islam, and that ketupat likely evolved from older Austronesian culinary and ritual practices.[25]

Ketupat in Malay Sources

Early written references to ketupat in the Malay world appear in both foreign and local sources dating to the period of the Malacca Sultanate. A Chinese–Malay vocabulary compiled between 1403 and 1511 includes the term tu pa, referring to rice cakes cooked in woven palm or coconut leaf pouches. This suggests that such rice-based dishes were already an established part of Malay culinary traditions by the early 15th century, reflecting broader Austronesian food practices.[26]

In literature, the term ketupat is first recorded in the 16th-century Hikayat Inderaputera, a courtly romance that includes ketupat among the cultural elements of aristocratic life. These sources suggest that ketupat had become an established part of both daily cuisine and cultural expression in the Malay world by the late Malacca Sultanate and early post-Malacca era.[1][27]

Religious and spiritual significance

Role in Balinese Hindu Rituals and Offerings

In Hindu-majority regions of Indonesia, particularly in Bali and parts of Java, ketupat plays an important role in religious rituals and ceremonial offerings. In Balinese Hinduism, ketupat, locally known as tipat, is included in temple offerings (banten) presented to Dewi Sri, the goddess of rice, fertility and prosperity.[23][24] During the Kuningan festival, which marks the conclusion of the Galungan celebrations, Balinese families prepare and weave tipat as part of offerings to honour ancestral spirits and celebrate the triumph of dharma over adharma.[11] The woven palm leaf and the rice within symbolise gratitude for sustenance and spiritual harmony. Following the ceremony, the tipat may also be consumed.

A key element in the Galungan and Kuningan celebrations, ketupat is typically offered alongside other symbolic foods and placed near the penjor, a tall decorated bamboo pole adorned with young palm leaves and set up outside homes and temples. These ritual practices express the importance of agriculture, ancestral reverence and balance in the cosmos, reflecting core elements of Balinese cosmology.[11]

Islamic Traditions and the Role of Ketupat during Lebaran

The tradition of preparing and consuming ketupat during Eid al-Fitr is widely observed across maritime Southeast Asia, particularly in Indonesia, Malaysia, Brunei, Singapore and southern Thailand. In these regions, ketupat has become a cultural symbol marking the conclusion of the fasting month of Ramadan. It is commonly served alongside various festive dishes during family gatherings and open house celebrations, and is considered an integral part of Eid festivities.

In Indonesia, particularly on the island of Java, ketupat holds deep religious and cultural significance, especially during Lebaran (Eid al-Fitr). Its symbolic use is widely associated with the efforts of the Wali Songo, the nine revered saints credited with spreading Islam in Java during the 15th century. Sunan Kalijaga, in particular, is traditionally believed to have introduced Bakda Ketupat, a celebration held a few days after Eid, which incorporates ketupat as a meaningful part of the festivities.[28]

The association between ketupat and Lebaran is believed to have originated in the Sultanate of Demak, one of Java’s earliest Islamic kingdoms. Sunan Bonang, another prominent Wali Songo figure, is said to have emphasised the importance of seeking forgiveness and reconciliation as part of the post-Ramadhan observance.[29] This teaching became an integral aspect of Lebaran, during which ketupat serves not only as festive food but also as a symbol of purification, humility and restored social harmony.

Ketupat in Javanese and Sundanese Spiritual Traditions

In Java, ketupat is also featured in sajen (ritual offerings) within indigenous traditions such as Kejawen and Sunda Wiwitan. It may be placed on household altars or suspended at doorways during spiritual observances to welcome ancestral spirits believed to return temporarily to the earthly realm. These practices reflect ketupat’s role not only as nourishment but also as a ritual object symbolising the connection between the material and spiritual worlds in traditional Javanese and Sundanese cosmology.[23]

Ketupat in Malay Main Teri Rituals

In Kelantan, Malaysia and Pattani, Thailand, ketupat is used in the traditional healing ritual known as Main Teri, which was historically practised by segments of the Malay community. The ritual involves music, trance, symbolic gestures and recitations by a practitioner known as the Tok Teri. It has been described as a form of psycho-spiritual healing rooted in local beliefs and cultural expressions.[30]

As part of the ceremonial setting, a pavilion (balai) is decorated with ritual offerings such as ketupat, traditional cakes like putu and fragrant flowers. Young coconut leaves are folded into ornamental shapes including ketupat and grasshoppers, then arranged around the space. These elements are believed to serve symbolic purposes or appeal to unseen spiritual entities according to local cosmology.[31]

Although once considered an important part of traditional medicine and community healing, Main Puteri has declined significantly in recent decades. This decline is due to a combination of factors including growing public access to modern healthcare, changing social attitudes and increased religious awareness. The decline has also been influenced by criticisms from Islamic scholars and religious authorities, who view certain aspects of the ritual as incompatible with Islamic teachings.[32]

Spiritual Significance among the Orang Asli

Ketupat burung is a type of decorative ketupat woven to resemble a bird, complete with a beak, wings and tail. It is traditionally made using a single coconut leaf that has been split in half and stripped of its midrib. Although it can technically be used for cooking, this form of ketupat is typically not used as a food container. Instead, ketupat burung serves a symbolic function in sewang ceremonies, which are ritual healing practices performed by some Indigenous Orang Asli communities in Malaysia. In this context, the bird-shaped ketupat is believed to carry spiritual significance within the framework of traditional healing and animistic belief systems.

Symbolism in Dayak Ceremonial Practices

Among Dayak communities in Central Kalimantan, ketupat is used in religious and ceremonial offerings as a representation of harmony between humans, nature and the spiritual realm. Its woven form, made from young coconut leaves, symbolises the complexity of life and the connection between people and their ancestors. Ketupat is commonly included in rituals such as Pakanan Batu and Manyanggar, which are conducted to honour guardian spirits of forests and rice fields, and to give thanks for bountiful harvests.[33]

Ketupat in Cina Benteng Ancestral Traditions

Among Chinese Indonesian communities, particularly the Cina Benteng of Tangerang, ketupat is sometimes included in offerings during sembahyang Imlek (Chinese New Year prayer rituals). While not traditionally part of Chinese cuisine, ketupat has been incorporated into local practice alongside items such as lepet and various traditional snacks. Its inclusion reflects the syncretic nature of Chinese Indonesian culture, where ancestral veneration often blends with regional customs and symbolic foods.[34]

Cultural traditions and celebrations

Symbolic and Decorative Use

In Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and Brunei, ketupat motifs made from colourful ribbons or plastic are commonly used as festive decorations during Hari Raya Aidilfitri. Known as ribbon ketupat, these ornamental versions are typically hung in homes, shopping centres and public spaces, often alongside oil lamps (pelita) and festive lights to create a celebratory atmosphere. While ketupat is traditionally a food item, its woven diamond-shaped form has become a widely recognised symbol of the holiday.[35]

Ketupat in Syawal Festivities

In several regions of Indonesia, the days following Idul Fitri are marked by local traditions centred on ketupat. These post-Eid celebrations, commonly referred to as kupatan, reflect a blend of Islamic observance and local cultural practices. In Lombok, the Lebaran Topat tradition is observed on the sixth day of Syawal. Rooted in the syncretic Waktu Telu tradition, the celebration includes pilgrimages to sites such as Makam Loang Baloq and Makam Bintaro, ritual activities including berseraup (ritual washing) and ngurisan (baby hair-cutting), and culminates in the Perang Topat (Ketupat battle) at Pura Lingsar, a temple shared by Muslims and Hindus. The event symbolises interreligious harmony and social purification, while ketupat serves as a symbol of community ties and spiritual reflection.[36]

In Gorontalo, a similar tradition known as Ketupat Lebaran Jaton takes place on the seventh day of Syawal. It was introduced by the Jawa-Tondano community, who migrated from Minahasa in the early 20th century. Centred in Yosonegoro village, the celebration involves communal prayers and an open-table practice in which residents provide food to anyone passing by. Folk festivities, such as horse racing and cattle contests, are also held. Although not originally native to the region, the tradition has been adopted more broadly and is regarded as a means of strengthening social ties and promoting generosity.[36]

In East Java, the village of Durenan in Trenggalek holds Kupatan Durenan on the eighth day of Syawal, coinciding with the completion of six days of the Syawal fast. The tradition is attributed to KH Imam Mahyin of Pondok Pesantren Babul Ulum, who initiated the practice in the 19th century. Households prepare ketupat in large quantities to serve guests during open house gatherings. Unlike most regions where visiting typically occurs on the first day of Idul Fitri, residents of Durenan reserve such visits for Hari Kupatan, which serves as the primary occasion for community-wide social interaction. In Lamongan, Lebaran Kupat is celebrated on 7 Syawal with the Festival Kupatan Tanjung Kodok, rooted in the teachings of Sunan Sendang Duwur. The festival features communal feasting, pawai gunungan ketupat (a procession of cone-shaped ketupat offerings), cultural performances and culinary demonstrations, aimed at preserving tradition and promoting tourism.[37]

In Central Java, the post-Eid celebration is known as Bada Kupat, during which families prepare both ketupat and lepet. In Kudus Regency, the celebration features a gunungan parade—cone-shaped offerings made from ketupat, lepet and other foods—carried in procession to the grave of Sunan Muria on Mount Muria. In Boyolali Regency, a procession of livestock decorated with ketupat forms part of the local festivities[28]

Ketupat in Lebaran and Galungan–Kuningan Celebrations

There are notable similarities between the Javanese Muslim celebration of Lebaran and the Balinese Hindu observance of the Galungan and Kuningan holy days, in which ketupat features prominently. In both traditions, families visit the graves of deceased relatives before the commencement of the religious festivities and ketupat is consumed as part of the concluding rituals. Although ketupat is widely associated today with the Muslim celebration of Eid al-Fitr in Indonesia, these parallels suggest a pre-Islamic origin rooted in indigenous cultural practices.[11]

Charitable Practices Involving Ketupat

The tradition of sedekah ketupat, which involves the offering and distribution of ketupat, is practised across various regions in Indonesia with distinct cultural and religious expressions.

In western Cilacap, particularly in the Sundanese-influenced districts of Tambaksari and Dayeuhluhur, sedekah ketupat is held during Rebo Wekasan, the final Wednesday of the Islamic month of Safar. The event is rooted in local beliefs associated with the potential misfortune of the day. Villagers hang ketupat at village borders, gather for communal prayers, and consume the ketupat together as a symbolic act of protection and gratitude. In some areas, the practice has evolved into a cultural festival featuring processions and gunungan, large decorative structures made of ketupat, while maintaining its spiritual significance.[38]

In Central Java, particularly in Dusun Gledek, Desa Podosoko, Candimulyo in Magelang Regency, sedekah ketupat takes the form of charitable distribution ahead of Lebaran. Community members, dressed in traditional sorjan attire, go from house to house delivering ketupat, rice and basic food items to underprivileged residents. Recipients are encouraged to cook the ketupat with coconut milk (toyo santen), symbolising a request for forgiveness (sedoyo lepat nyuwun pangapunten). The practice fosters social cohesion and includes both Muslim and non-Muslim participants.[39]

Mid-Ramadan Ketupat Traditions

In Betawi culture, the tradition of malam ketupat or ketupat qunut is observed during the second half of Ramadan, particularly on the 15th night or on the odd-numbered nights following the 17th of Ramadan (malam likuran). On these evenings, Betawi families prepare ketupat along with accompanying dishes such as sayur labu (gourd curry) and side dishes, which are brought to local mosques or prayer houses (musala) as communal offerings. The practice is often accompanied by the sharing of traditional snacks such as kue abug, a steamed kue filled with palm sugar and grated coconut.[40] The tradition is typically held after the tarawih prayers, followed by communal recitations of Yasin and Tahlil, and concludes with the collective meal. It serves as an expression of gratitude for having reached the midpoint or final stretch of Ramadan and as an opportunity for charity and community bonding. The ketupat, beyond its role as festive food, symbolises unity, humility and shared blessings during the holy month.[40]

In Maluku, the Muslim community in the village of Kaitetu, Leihitu subdistrict on Ambon Island observes sedekah ketupat towards the end of Lailatul Qadar during Ramadan. Each family donates ketupat in accordance with the number of household members, offering them to mosque elders (penghulu) at Masjid Wapauwe, one of the oldest mosques in the region, and at other local places of worship. The offering expresses gratitude for the leadership of Ramadan prayers and is followed by prayers for the wellbeing of the donors. One ketupat is ceremonially returned to each household and its wrapper is hung in the home as a symbolic doa tolak bala (prayer to ward off misfortune). The tradition also serves as an informal census and reflects a long-standing integration of religious and communal values. Members of the local nobility traditionally contribute agricultural produce instead of ketupat.[41]

Ketupat Lepas Tradition

Ketupat Lepas is a ritual tradition observed by the Malay community in the village of Kudung, East Lingga District, part of the Lingga Archipelago in the Riau Islands. Held annually during the month of Muharram, the tradition involves communal prayers at the mosque, attended by both men and women, followed by a shared meal prepared from food brought by each household.[42] After the prayers, participants gather at the river to ceremonially release the wrappings of ketupat into the water. This act symbolises a spiritual cleansing, letting go of misfortune and returning to a state of purity for the new year. Two types of ketupat lepas are made: the larger jantan (male), and the smaller betina (female), both representing the importance of collective responsibility in resolving communal challenges.[42]

Ketupat during Christmas and New Year Celebrations

In Palu, Central Sulawesi, ketupat is not only prepared for Islamic celebrations such as Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha, but is also commonly served by members of the local Christian community during Christmas and New Year. Seasonal vendors begin offering ketupat in the days leading up to 25 December, reflecting a regional tradition in which the dish is shared across religious communities as part of broader festive observances.[43]

Ceremonial Use of Ketupat in Symbolic Battles

One of the most distinctive ceremonial uses of ketupat in the region is found in traditional mock battles known as Perang Ketupat or ketupat wars, held in areas such as Bangka Belitung, Sanggau, Lombok and Bali. While each version differs in context and meaning, they all involve the symbolic throwing of ketupat and reflect shared values of protection, gratitude, and social harmony.

At the royal palace of Tayan in Sanggau Regency, West Kalimantan, the traditional ceremonies of Mandi Bedil and Perang Ketupat are preserved as part of the local cultural heritage. Mandi Bedil involves the ritual cleansing of royal heirlooms such as keris, swords, spears and cannons, and is believed to date back to the founding of the Tayan Kingdom under Raja Gusti Lekar. Meanwhile, Perang Ketupat is a symbolic ritual in which residents on land and those on boats in the river throw ketupat at one another as a form of communal protection against misfortune.[44]

In Bangka Belitung, the tradition known as Ruah tempilang takes place on Tempilang Beach, typically before Ramadan or during the Islamic New Year. Participants throw ketupat at one another to symbolically cleanse the community and ward off misfortune. The practice is believed to have originated in the eighteenth century as a communal response to pirate threats and foreign incursions. The event usually begins with residents welcoming guests into their homes, followed by a spirited ketupat throwing ritual signalled by a cannon blast. A miniature boat is also floated out to sea to symbolically carry away unseen forces.[45]

In Lombok, a similar tradition called Perang Topat is held at Pura Lingsar, a temple revered by both Muslims and Hindus. During the event, members of both communities toss ketupat at each other in a festive and friendly manner. The tradition symbolises peaceful coexistence and is believed to bring blessings of fertility to local agriculture.[46]

In Bali, ketupat is used in the Aci Rah Pengangon ritual, a thanksgiving ceremony to express gratitude for the year’s blessings. Ketupat are included as ritual offerings and thrown in a ceremonial gesture that aligns with local spiritual and agricultural rhythms.[47]

Ceremonial Use in Bisaya Infant Rites

Among the Bisaya people of Sabah, a distinctive variant of ketupat known as Talimbu Lapas is featured in the Adat Mencukur Jambul, a traditional infant hair-cutting ceremony. This loosely woven ketupat is filled with yellow glutinous rice and is intentionally designed to unravel easily. Following the ritual shaving of the infant’s hair, the ketupat is pulled apart to scatter the rice, a symbolic gesture signifying the fulfilment of a religious vow (nazar). The ceremony customarily concludes with the distribution of alms.[48][49]

Varieties

There are numerous regional varieties of ketupat found across Southeast Asia, prepared using either regular or glutinous rice and traditionally wrapped in woven palm leaves. While coconut palm leaves are the most commonly used materials, some local adaptations employ alternative wrappings such as nipah palm or pandan leaves. The following are some notable regional variants:

Ketupat darlamu/ tamanggung

Ketupat darlamu, also known as ketupat dalamu, is a traditional Bruneian Malay variety of ketupat. It is characterised by a seven-pointed woven casing (kelongsong) that is generally larger than typical ketupat. Its most distinctive feature is the sharply raised corners on both sides, giving it a unique shape compared to other local variants, including the similarly shaped but smaller ketupat tamanggung.[50]

Katupek bareh

Katupek bareh is a traditional variety of ketupat originating from the Minangkabau people of West Sumatra, Indonesia. It is also commonly found along the western coast of North Sumatra, particularly in the city of Sibolga. Unlike standard ketupat, which is usually boiled in water, Katupek bareh is made from white rice cooked in coconut milk, resulting in a firmer texture and a savoury, aromatic flavour. The dish is typically served with sambal kelapa (spiced grated coconut) and asam padeh ikan, a tangy and spicy fish stew. Katupek Bareh is often prepared for festive occasions, family gatherings and community events.[51]

Ketupat landan

Ketupat landan is a unique variation of ketupat traditionally made in Desa Kecitran, Banjarnegara Regency, Central Java and is typically prepared only for Eid al-Fitr. Its distinctive feature is the use of air landan, which is alkaline water extracted from the ash of burnt coconut fronds, to boil the ketupat. This gives it a dark reddish hue and a slightly salty, savoury flavour, unlike regular ketupat which is typically neutral in taste. The alkaline water not only enhances flavour but also helps preserve the ketupat for several days without refrigeration. Ketupat landan is commonly served with dishes such as opor ayam, sate or the locally favoured ayam petis, combining rich, spicy and umami notes in one meal.[52]

Ketupat daun palas

Ketupat palas, also known as ketupat daun palas, is a traditional variety of ketupat commonly found in northern and eastern Peninsular Malaysia, southern Thailand and parts of North Sumatra, particularly among Malay communities. It is made using palas (licuala) leaves instead of the more widespread young coconut leaves and is typically folded into a triangular shape. Unlike regular ketupat made with ordinary rice, ketupat palas uses glutinous rice (pulut), often partially cooked and mixed with coconut milk, pandan leaves, salt or sugar for added flavour. Once wrapped and tied tightly, it is boiled or steamed until fully cooked and is often served during festive occasions such as Hari Raya.[8]

Ketupat daun kapau

Ketupat daun kapau is a traditional variety of ketupat associated with Malay communities in Pekanbaru and the wider coastal regions of Riau, Indonesia. It is distinguished by the use of daun kapau, a type of leaf harvested from peat swamp vegetation, which gives the rice cake a clean white colour, a distinctive aroma and a longer shelf life compared to ketupat wrapped in young coconut or palm leaves. This variety is particularly popular during Eid al-Fitr, when it is prepared and sold in large quantities by local artisans, especially along Jalan Meranti near the Siak River. Although once widespread, the practice has declined due to the decreasing availability of the raw materials and a shrinking number of craftspeople skilled in weaving the traditional wrappings.[53]

Katupa'

Katupa is a type of ketupat from South Sulawesi, particularly among the Makassarese community. Unlike most ketupat, which are wrapped in young coconut leaves, katupa uses pandan leaves, giving it a darker green colour and a distinct aroma. It is typically boiled for several hours. Katupa is commonly eaten during Lebaran and is also a staple accompaniment to dishes like Coto Makassar.[10]

Ketupat jembut

Ketupat jembut is a unique variation of ketupat originating from Semarang, Central Java, traditionally associated with the Syawalan or Lebaran Ketupat celebrations held after Eid al-Fitr. Unlike regular ketupat, it is filled not only with rice but also with simple vegetables such as bean sprouts, shredded cabbage and spiced grated coconut, creating a textured surface and savoury flavour that requires no additional side dishes. The name, which literally means "pubic ketupat" in Javanese, is derived from its visual resemblance due to the inclusion of sprouts partially visible through a diagonal cut in the ketupat casing, which is made from young coconut or bamboo leaves. Believed to have originated in the 1950s in the village of Jaten Cilik by refugees from Demak, the dish was a creative response to limited food supplies during Ramadan. In later years, especially from the 2000s, the ketupat also became a medium for THR (holiday allowances), with money tucked inside and distributed to children as part of the festive tradition.[54]

Ketupat balamak

Ketupat balamak is a regional variation of ketupat from Kandangan, South Kalimantan, Indonesia. Unlike the better-known ketupat Kandangan served with coconut milk gravy and grilled snakehead fish, ketupat balamak is boiled in coconut milk with salt and served dry, typically accompanied by a variety of local sambals such as peanut sauce, sate-style sauce, sambal nagara or sambal terasi mixed with grated coconut and dried shrimp (ebi). It is especially popular during the month of Ramadan, widely sold at the Kandangan Ramadan Market and eaten with salted duck eggs. Although less commonly found at restaurants, it is regularly sold at morning markets and food stalls during festive seasons.[9]

Kupat sumpil

Kupat sumpil is a distinctive variety of ketupat from Central Java, characterised by its small triangular shape and the use of bamboo leaves instead of the more typical coconut fronds as wrapping. It is commonly served as a substitute for steamed rice and eaten with dishes such as opor ayam, sate, ketoprak or ketupat sayur. While kupat sumpil is available throughout the year in local markets such as Pasar Gladak and Pasar Pagi in Kaliwungu, Kendal, it also features prominently in local cultural traditions. The dish is often prepared and shared by the people of Kaliwungu during the weh-wehan celebration, a communal festivity held in conjunction with the commemoration of the Prophet Muhammad’s birthday (Maulid Nabi Muhammad).[55][56]

Derivative dishes

Ketupat is traditionally served by Indonesians and Malays during festive occasions, especially during Lebaran or Idul Fitri (Hari Raya Aidilfitri), often at open houses. Ketupat is commonly accompanied by dishes such as opor ayam (chicken stewed in coconut milk), chicken or beef curry, rendang, sambal goreng ati (spiced beef liver), krechek (spicy stewed buffalo or beef skin) and sayur labu Siam (chayote soup). Ketupat and its close variant lontong are also used as alternatives to plain steamed rice in dishes like gado-gado, soto, karedok and pecel.

Beyond its role as a rice substitute, ketupat has inspired a number of derivative dishes in which it serves as a central component rather than a side. These include distinctive regional preparations that incorporate local ingredients, cooking techniques and flavour profiles. The following are some notable examples:

Ketoprak

Ketoprak is a traditional vegetarian street food dish from Jakarta, Indonesia, popular among the Betawi and broader urban communities. Typically served at roadside stalls, it consists of fried tofu, rice vermicelli (bihun), bean sprouts, cucumber and steamed rice cake (lontong or ketupat), all doused in a rich, sweet-spicy peanut sauce made from ground peanuts, garlic, chili, palm sugar, salt and sweet soy sauce (kecap manis). Common garnishes include krupuk (crackers) and fried shallots, with some versions adding a boiled egg. The dish's name is sometimes explained as a Betawi acronym: ket (ketupat), to (tahu and toge) and prak (crushed), referring to its key ingredients and preparation, although another folk etymology attributes it to the clattering sound of plates associated with street vendors.[57][58]

Ketupat sotong

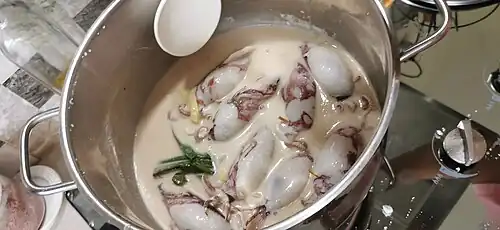

Ketupat Sotong is a traditional Malaysian dish originating from the east coast states of Terengganu and Kelantan. It consists of whole squids (sotong) stuffed with glutinous rice (pulut) and simmered in rich coconut milk. The rice is typically pre-soaked or partially cooked, sometimes mixed with coconut milk and salt, then inserted into the squid and secured before cooking. The dish is commonly served during festive occasions such as Hari Raya Aidilfitri and is known for its unique combination of textures, with tender squid encasing sticky, aromatic rice.

Regional variations reflect local taste preferences. In Terengganu, Ketupat Sotong is generally savoury, featuring a lighter coconut broth spiced with ingredients such as pandan leaves, ginger and fenugreek. In contrast, the Kelantanese version often includes palm sugar (gula melaka), resulting in a sweeter, caramel-like gravy.[59]

Ketupat kandangan

Ketupat Kandangan is a traditional dish originating from Kandangan, the capital of Hulu Sungai Selatan Regency in South Kalimantan, Indonesia. It features ketupat served with grilled fish in a rich, spiced coconut milk gravy. The dish commonly uses snakehead fish (ikan gabus), though gourami or catfish may also be substituted. The fish is first grilled to deepen its flavour before being simmered in a coconut-based sauce seasoned with aromatic spices such as cinnamon, nutmeg, cloves and cardamom.

The resulting gravy is slightly thick and fragrant, contributing to the dish’s distinctive character. Ketupat Kandangan is closely tied to the riverine culture of South Kalimantan and is often enjoyed during festive or communal gatherings. While some diners prefer the sauce poured over the ketupat, others serve the components separately.[60]

Ketupat sayur

.jpg)

One of the popular street foods in Indonesia is ketupat sayur, which literally means "vegetable ketupat." The dish consists of ketupat served in a thin, spicy coconut milk soup, typically prepared with vegetables such as labu siam (chayote) or unripe jackfruit. It is commonly garnished with cooked tofu, telur pindang (spiced boiled egg) and krupuk (crackers). When lontong is used in place of ketupat, the dish is known as lontong sayur.

Ketupat sayur is widely consumed as a breakfast dish and is particularly associated with two regional variants: the Betawi version from Jakarta and katupek sayua, the Minangkabau version from West Sumatra. The Betawi style is generally simpler, while the Padang (Minangkabau) version tends to be more elaborate, often accompanied by side dishes such as rendang, gulai or telur balado. Both variants are commonly sold by street vendors, especially in the mornings.

Kupat tahu

Ketupat is also a key ingredient in the traditional Sundanese and Javanese dish kupat tahu. The dish typically consists of ketupat, tahu goreng (fried tofu) and bean sprouts, served with a savoury peanut sauce and topped with crispy krupuk (crackers). It is a popular street food and breakfast dish across Java, with several well-known regional variations.

Notable variants include Kupat Tahu Kuningan from Kuningan Regency in West Java, Kupat Tahu Padalarang from Padalarang in West Bandung, Kupat Tahu Bandung in the city of Bandung, Kupat Tahu Bumiayu from Brebes Regency and Kupat Tahu Magelang from Magelang Regency in Central Java. Each variation may feature slight differences in sauce composition, toppings or accompaniments, reflecting local taste preferences.[61][62]

Tipat cantok

In Bali, a local variation of ketupat known as tipat cantok is a popular traditional dish. It consists of sliced ketupat served with blanched or boiled vegetables such as long beans, water spinach, bean sprouts, cucumber and fried tofu, all mixed in a savoury peanut sauce. The sauce is typically made from ground fried peanuts, garlic, chili peppers, salt and tauco (fermented soybean paste).)[63] The level of spiciness varies depending on the amount of chili used. Tipat cantok is one of the few Balinese dishes that are traditionally vegetarian. It shares similarities with Javanese pecel and the Betawi dish gado-gado, particularly in its use of peanut sauce and mixed vegetables.

Kupat glabed

Kupat glabed is a traditional dish from Tegal, Central Java, Indonesia, consisting of ketupat served with a thick yellow gravy. The name glabed derives from a local Javanese word describing a viscous, slurpy texture, aptly reflecting the dish’s rich, savoury sauce, which is thickened with maize starch to create a consistency resembling cream soup. Kupat glabed is typically topped with shredded chicken and a generous heap of kerupuk kuning, whose crumbled bits often cover the entire surface of the dish. It is commonly sold by street vendors or served at roadside stalls (warung lesehan).

Although visually similar to chicken opor, a common festive dish served during Eid, kupat glabed is distinguished by its thicker gravy and distinctive street food presentation. The dish is a local favourite in Tegal and is often eaten as a hearty evening meal. It is also frequently accompanied by side dishes such as offal satay or sate blengong (duck-goose satay).[64]

Local variations

-

Tipat Kuah, a Balinese specialty

Tipat Kuah, a Balinese specialty -

A gado-gado street stall featuring ketupat

-

Kupat sumpil, a triangular ketupat wrapped in bamboo leaves

Kupat sumpil, a triangular ketupat wrapped in bamboo leaves -

Ketupat Sotong from Terengganu

Ketupat Sotong from Terengganu -

Ketupat mie commonly found in Martapura

Ketupat mie commonly found in Martapura

Similar dishes

Variations of this practice are found across the region. In southern Thailand, a dish known as khao tom sam liap (ข้าวต้มสามเหลี่ยม), or tom bai kaphor, consists of glutinous rice steamed inside triangular-shaped palm leaf pouches. It is commonly prepared for cultural and religious festivals, including Sart Duean Sib (ancestral merit day), the Chak Phra procession and ordination ceremonies. Traditionally made with plain white or black glutinous rice, contemporary versions may include fillings such as mung beans, pork floss, sweet egg threads or bananas. Like ketupat, this dish exemplifies the adaptation of leaf-wrapping techniques to local customs and ritual contexts.[65][66]

In the Philippines, similar rice pouches are known as puso (literally "heart") and had their origins from pre-colonial animistic ritual offerings as recorded by Spanish historians. Unlike ketupat, however, they are not restricted to diamond shapes and can come in a wide variety of weaving styles (including bird and other animal forms) which still survive among various ethnic groups in the Philippines today. Ketupat are also woven differently; the leaf base and the loose leaf strands do not exit at the same point, as in most Filipino puso. Ketupat somewhat resemble the tamu pinad version among Muslim Filipinos the most, which are shaped like a flattened diamond, although they are also woven differently.

In Cambodia, a similar dish of pounded sticky rice wrapped in a pentagonal woven palm leaf is called katom (កាតំ) in Khmer. It is a non-traditional variant of num kom which uses banana leaves instead of palm.[67][68] In Indonesia, similar dish of compressed rice in leaf container includes lepet, lontong, lemper, arem-arem and bacang.

In China, there is a similar dish called lap (苙) that is a local speciality of the island of Hainan.[69] Hainanese lap is usually bigger in size than Indonesia's ketupat. Lap skin might be woven into pillow-shaped or triangular, the sticky rice is filled with pork belly. Outside China, lap can also can be found in Port Dickson in Malaysia and Singapore.[70]

See also

References

- ^ a b "Hikayat Indraputra A Malay Romance". 2024. Retrieved 23 July 2025.

- ^ a b c d "Penutur Austronesia Dan Cara Penyebarannya: Pendekatan Arkeologi, Genetik Dan Linguistik" (PDF) (in Malay). December 2017. Retrieved 23 July 2025.

- ^ a b "Bukti Penyebaran Bahasa Austronesia" (in Malay). 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2025.

- ^ a b "Makna di Balik Ketupat yang Berbentuk Persegi Empat" (in Indonesian). 1 June 2019. Retrieved 23 July 2025.

- ^ Rianti, Angelina; Novenia, Agnes E.; Christopher, Alvin; Lestari, Devi; Parassih, Elfa K. (March 2018). "Ketupat as traditional food of Indonesian culture". Journal of Ethnic Foods. 5 (1): 4–9. doi:10.1016/j.jef.2018.01.001.

- ^ "Asal usul dan simbolik di sebalik ketupat, juadah popular di hari raya" (in Malay).

- ^ "Ketupat di Medan: Sejarah, Makna dan Kuliner Khasnya" (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2 August 2025.

- ^ a b "Ketupat Palas" (in Malay). Retrieved 31 July 2025.

- ^ a b "Menu Ramadhan 1440 H, Ketupat Balamak Jadi Sajian Khas Pasar Ramadhan di HSS, Ada 4 Varian Sambelnya". banjarmasin.tribunnews.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ a b "Perbedaan Antara Ketupat Jawa dan Katupa Makassar, Catatan Nur Terbit" (in Indonesian). Retrieved 31 July 2025.

- ^ a b c d "Galungan Mirip Lebaran". Bali Post (in Indonesian). 10 October 2009. Archived from the original on 22 January 2015. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- ^ "Calories in indonesian food ketupat sayur". My Fitness Pal. Archived from the original on 3 June 2019. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- ^ "Ketupat Makanan Di Hari Raya" (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2 August 2025.

- ^ a b "Asal-usul Ketupat, Ciri Khas Saat Lebaran" (in Indonesian). 5 April 2023. Retrieved 15 June 2025.

- ^ "Prasejarah Austronesia Di Nusa Tenggara Timur" (in Indonesian). 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2025.

- ^ "Here's How a Humble Roadside Shop Makes Patupat". Retrieved 23 July 2025.

- ^ "Weaving coconut leaves into a katupat or rice pouch". 23 March 2025. Retrieved 23 July 2025.

- ^ a b "Fouha Bay: Cradle of Creation". Retrieved 23 July 2025.

- ^ Cunningham, Lawrence J. (1992). Ancient Chamorro Society. Bess Press. p. 140. ISBN 9781880188057.

- ^ Hunter-Anderson, Rosalind; Thompson, Gillian B.; Moore, Darlene R. (1995). "Rice As a Prehistoric Valuable in the Mariana Islands, Micronesia". Asian Perspectives. 34 (1): 69–89. JSTOR 42928340.

- ^ "A Record of the Buddhist Religion as Practised in India and the Malay Archipelago (A.D. 671-695)". 1896. Retrieved 23 July 2025.

- ^ "Ini kehebatan Ketupat, sejarah dan fungsinya yang ramai orang tidak tahu" (in Malay). Retrieved 23 July 2025.

- ^ a b c Setiawan, Sigit. "Akulturasi Budaya Jawa dengan Islam Melalui Ketupat". IDN Times (in Indonesian). Retrieved 29 June 2023.

- ^ a b Jay Akbar (11 August 2010). "Mengunyah Sejarah Ketupat" (in Indonesian). Historia. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- ^ Pitaloka, Dyah Ayu. "Ketupat: Jejak panjang dan filosofi di baliknya". rappler.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 23 April 2024.

- ^ "A Chinese Vocabulary of Malacca Malay Words and Phrases Collected between A. D. 1403 and 1511". 1931. Retrieved 23 July 2025.

- ^ "Soother of sorrows or seducer of morals? The Malay Hikayat Inderaputera". 2015. Retrieved 23 July 2025.

- ^ a b Panca Nugraha and Suherdjoko (5 August 2014). "Muslims celebrate Lebaran Ketupat a week after Idul Fitri". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- ^ Mahfud MD: "Sejarah Lebaran"

- ^ "Dokumentasi perubatan tradisional Main Teri" (in Malay). Retrieved 2 August 2025.

- ^ "Ritual penyembuhan penyakit dalam main peteri di Kampung Paloh, Kelantan" (PDF) (in Malay). Retrieved 2 August 2025.

- ^ "'Main Puteri' Bercanggah Dengan Islam" (in Malay). Retrieved 2 August 2025.

- ^ "Ketupat Merupakan Prasarana Ritual Keagamaan Suku Dayak Kalteng" (in Indonesian). Retrieved 31 July 2025.

- ^ "Ketupat Sayur Imlek di Tangerang dan Sejarah Singkat Cina Benteng" (in Indonesian). Retrieved 31 July 2025.

- ^ "Excited for Raya 2025? Here's Everything You Need To Know About Hari Raya Aidilfitri!". Retrieved 2 August 2025.

- ^ a b "Mengintip Tradisi Ketupat Lebaran dari 3 Daerah di Indonesia, Makan Gratis hingga Perang-perangan" (in Indonesian). Retrieved 31 July 2025.

- ^ "Semarak Festival Kupatan Meriahkan Lebaran Ketupat di Lamongan" (in Indonesian). Retrieved 31 July 2025.

- ^ "Sedekah Ketupat, Adat Masyarakat Cilacap Barat Tangkal Bahaya di Rabu Wekasan Safar" (in Indonesian). Retrieved 31 July 2025.

- ^ "Ada 'sedekah ketupat' di Magelang" (in Indonesian). Retrieved 31 July 2025.

- ^ a b "Memaknai Tradisi Ketupat Qunut di Masjid Betawi" (in Indonesian). Retrieved 31 July 2025.

- ^ "Warga Kaitetu sedekah ketupat di malam Tujuh Likur" (in Indonesian). Retrieved 31 July 2025.

- ^ a b "Tradisi Ketupat Lepas" (in Indonesian). Retrieved 31 July 2025.

- ^ "Ketupat Juga Dihidangkan saat Perayaan Natal di Palu". 25 December 2023. Retrieved 31 July 2025.

- ^ "Tradisi Mandi Bedil dan Perang Ketupat Sebagai Wujud Sanggau Berbudaya" (in Indonesian). Retrieved 31 July 2025.

- ^ "Tradisi Perang Ketupat di Babel Dipercaya Bersihkan Kampung dan Tolak Bala" (in Indonesian). Retrieved 31 July 2025.

- ^ "Perang Ketupat di Lombok Simbol Kesuburan Pertanian" (in Indonesian). Retrieved 31 July 2025.

- ^ "Mengenal Tradisi Perang Ketupat di Bali" (in Indonesian). Retrieved 31 July 2025.

- ^ "Adat Resam Dan Pantang Larang Suku Kaum Di Sabah" (in Malay). Retrieved 2 August 2025.

- ^ "Pertemuan antar Adat dan Agama dalam Upacara Talimbu Lapas dalam Masyarakat Bisaya: Studi di Kampung Mansud Sabah, Malaysia" (in Malay). Retrieved 2 August 2025.

- ^ "Ketupat Darlamu/ Tamanggung". www.kkbs.gov.bn. Retrieved 3 August 2025.

- ^ "Katupek Bareh" (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2 August 2025.

- ^ Cahyono, Budi. "Mengenal Ketupat Landan Khas Banjarnegara dan Cara Membuatnya". ayosemarang.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- ^ "Ketupat Daun Kapau, Sebuah Tradisi Warisan Leluhur di Kampung Bandar" (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2 August 2025.

- ^ "Ketupat Jembut, Kuliner Semarangan Penuh Makna Kesederhanaan". cnnindonesia.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ "Ketupat Sumpil Makanan Khas Kaliwungi Kendal" (in Indonesian). 3 March 2023. Retrieved 4 August 2025.

- ^ "Ketupat Sumpil Sudah Dikenal Sejak Zaman Sunan" (in Indonesian). 11 March 2023. Retrieved 4 August 2025.

- ^ "Ketoprak Recipe (Indonesian Vermicelli Salad With Spicy Peanut Sauce)". Retrieved 2 August 2025.

- ^ "Ketoprak / Vermicelli tofu salad and peanut dressing". Retrieved 2 August 2025.

- ^ "Ketupat Sotong" (in Malay). Retrieved 2 August 2025.

- ^ Sabandar, Switzy. "Ketupat Kandangan, Kuliner Simbol Kedekatan Masyarakat Kalsel dengan Alam". liputan6.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 4 May 2023.

- ^ Nugraha, Nalarya. "3 Kupat Tahu Enak di Bandung". pikiran-rakyat.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ Lestari, Devi Setya. "Cicipi Nikmatnya Kupat Tahu Bumiayu". okezone.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ Sri Lestari (20 January 2015). "Tipat Cantok, Kuliner Khas Bali yang Tak Membosankan". Kompas.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- ^ "Kupat Glabed, Sajian Mirip Opor Khas Tegal" (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2 August 2025.

- ^ "นร.โรงเรียนบ้านคลองขุดสืบสานวิธีทำ "ข้าวต้มสามเหลี่ยม" อาหารมงคลคนใต้" (in Thai). Retrieved 3 August 2025.

- ^ "Rice Dumplings: Thai "khao tom sam liap" versus Malay "ketupat palas"". Retrieved 3 August 2025.

- ^ Preap Kol (5 May 2008). "The Outstanding Youth Picnic". The Outstanding Youth Group of Cambodia. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- ^ Siem Pichnorak (16 July 2013). "Cambodian Rice Cakes". ASEAN-Korean Centre. Archived from the original on 20 January 2015. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- ^ "【悦食堂】仅在节庆海南笠飘香|中國報". 中國報 China Press. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ^ Roy, Big (4 November 2014). "My Encounter With The 'Lap' – Home Made, Singapore". eatwithroy. Retrieved 18 August 2020.