Jules Liégeois

Jules Liégeois | |

|---|---|

Jules Liégeois (1891) | |

| Born | Jules Joseph Liégeois 30 November 1833 Damvillers, France |

| Died | 14 August 1908 (aged 74) Bains-les-Bains, France |

| Occupation(s) | Jurist; university professor; psychologist |

| Known for | Administrative law; Political economy; Member of Nancy School; Hypnotic suggestion; Hypnotism and crime |

| Spouse | Hélène Marie Henriette Peiffer |

| Children | 2 |

| Awards | Knight of the Legion of Honour |

| Hypnosis |

|---|

Jules Joseph Liégeois (30 November 1833 — 14 August 1908), Knight of the Legion of Honour ("Chevalier de l'Ordre de la Légion d'Honneur"), and the Professor of administrative law at the University of Nancy for forty years, was a universally respected French jurist who was also widely known as an important foundation member, promoter, and defender of the Nancy School of Hypnosis — some would even say "the founder" of the School, not "just a participant" (Touzeil-Divina, 2024a).

In addition to his numerous influential publications on administrative law and the relationship between economics and the law, he was internationally recognized for the significance, scope, and systematic nature of his critical and innovative personal investigations into natural/spontaneous somnambulism, hypnotism, and hypnotic suggestion in the wider medico-legal domain. He "was the first forensic scientist to scientifically address the medical question of hypnotism",[1] and "was the leading researcher in the nineteenth century into the possibilities of the abuse of hypnosis for the purposes of crime",[2] not only in the sense of crimes committed upon a hypnotized subject, and those committed by a hypnotized subject, but also in the sense of the hypnotized subject subsequently having no memory of either circumstance.

Family

The son of Joseph-Martin Liégeois (1797-1854), a forester, and Anne-Rosalie Liégeois (1810-1890), née Tabutiaux, Jules Joseph Liégeois was born at Damvillers, Meuse, France on 30 November 1833.[3][4]

He married Hélène Marie Henriette Peiffer (1842-1935) in Nancy on 25 September 1867; they had two children: Marie Marguerite Liégeois (1868-1897), who married the linguist and philologist Ferdinand Brunot in 1891, and Jules Albert Liégeois (1875-1930), who went on to become an examining magistrate in Évreux.[4]

Academic career

His first employment was in various administrative roles — first, in the Meuse Departmen, at Bar-le-Duc (1851 to 1854), and then in the Meurthe Department, at Nancy (1854 to 1863) — and it was not until he was in his late 20s that he began formal legal studies at Strasbourg (there was no University in Nancy at that time).[4]

Having successfully submitted his Bachelor degree dissertation, Du prêt à intérêt en droit romain et en droit français ('Interest-bearing loans in Roman law and French law'), at the University of Strasbourg's Faculty of Law and Political Science in 1861, he went on to defend his doctoral dissertation, Essai sur l'histoire et la legislation de l'usure ('Essay on the History and Legislation of Usury'), at Strasbourg in 1863.[4]

Personally appointed directly by Victor Duruy, the Minister of Public Education (1863-1869), in October 1865,[4] he served as professor of administrative law (as distinct from civil and criminal law) at Nancy University from the University's re-establishment in 1865 until his retirement in 1904, when he became an honorary professor.

He published widely upon important matters of public and administrative law — including two important works (1873b, 1882b), jointly written with Louis Pierre Cabantous (1812-1872), Professor of Administrative Law, and Dean of the Faculty, at Aix-Marseille University — and on political economy and the relationship between economics and public law, many of which displayed the influence of the economic theories of Frédéric Bastiat:[4] e.g. 1858; 1861; 1863; 1865; 1867; 1873a; 1873b; 1873c; 1877; 1878; 1879; 1881a; 1881b; 1882a; 1882b; 1882c; 1883, and 1890a.[5]

The two French "Schools" of hypnotism (1882—1892)

It is significant that neither the "Salpêtrière School" (a.k.a. the "Paris School"), or "Hysteria School", nor the "Nancy School", or "Suggestion School",[6] as they are widely known, were "Schools" in the classical sense; neither, for instance, had an undisputed "master". However, as Mathieu Touzeil-Divina (2024a) observes, whilst the members of each group displayed as many differences of approach between themselves as points of agreement (that is, apart from their agreed-upon views on hypnotism and suggestion, and their opposition to the views of Charcot and the Salpêtrière School), it is still useful to speak of the two groups as competing "schools of thought", on the basis that the members of each group shared entirely different geographic, thematic, and chronological linkages from those that were shared by the members of the other group.

Peter (2024, p. 6) draws attention to the fact that, despite all of the subject-centred research conducted by a wide range of researchers with a wide range of theoretical orientations and disciplinary allegiances in the last 150 years into "[what] has always been regarded as a hallmark of hypnosis" — namely, "a non-judgemental, involuntary acceptance of suggestions", which, "[when] seen as a negative characteristic" is "a loss of control"[7] — the question of "whether such a suggestive-hypnotically induced loss of control is also possible in normal everyday life, [and] whether the hypnotized person is then helplessly at the mercy of the hypnotist" has never been unequivocally settled.[8][9]

"Hypnotism" and "hypnosis"

There is no objective evidence of any kind that the various allusions made by either of the Schools to "hypnotism" and "hypnosis" were, in fact, speaking of the same psychological circumstances and physiological arrangements; and, so, the two may well have been "talking past each other", rather than engaging in an actual dispute.[10]

"Suggestion School of Hypnosis" at Nancy

- "Hypnotism, like natural sleep, exalts the imagination, and makes the brain more susceptible to suggestion. ... It is a physiological law, that sleep puts the brain into such a psychical condition that the imagination accepts and recognizes as real the impressions transmitted to it. To provoke this special psychical condition by means of hypnotism, and to cultivate the suggestibility thus artificially increased with the aim of cure or relief, this is the role of psychotherapeutics." — Hippolyte Bernheim (1888, emphasis in original).[11]

Inspired by the theories and practices of the Nancy physician, former animal magnetist, and medical hypnotist, Ambroise-Auguste Liébeault (1823–1904),[12] the "Suggestion School" held that "hypnosis" was a state similar to sleep, and that it was produced by suggestion.

The first to associate himself with the experiments, principles, and practices of Liébeault was Liégeois, from the Nancy University's faculty of Law, "who had learned of Liébeault's practices by chance, and whose scientific curiosity had led him there",[13] then, a little later, came the initially sceptical Prof. Hippolyte Bernheim (1840–1919), the Nancy University's neurologist and physician, who had also learned of Liébeault's practices by chance,[13] and, finally, initially persuaded by Bernheim, came Prof. Henri-Étienne Beaunis (1830–1921),[13] who had held the chair of Physiology at Nancy University ever since the University had moved from Strasbourg to Nancy in 1872.[14][15]

In addition to their extensive personal experience of the successful hypnotization of a wide range of subjects in a wide range of circumstances — for instance, by 1897, Bernheim had already hypnotized "several hundred people", and Liébeault "[had] hypnotized more than six thousand persons during the [preceding] twenty-five years" (Bernheim, 1889, p. 90) — and their practical and theoretical studies of the phenomena of hypnotism and hypnotic suggestion in general, the members of the Nancy School also investigated the medical and legal aspects of their application:[16] with Berheim concentrating on their therapeutic aspects, Liégeois on their (civil and criminal) legal aspects, and Beaunis on their physiological and psychological aspects.[17][18]

"Hysteria School of Hypnosis" at the Salpêtrière, Paris

.tiff.jpg)

produced by a tuning fork's sound (Iconography of the Salpêtrière).[19]

- "At the very outset my studies dealt with hysterical women, and ever since I have always employed hysterical subjects.[21] ... [and] I have chosen rather to deal almost always with the female sex, because females are more sensitive and more manageable than males in the hypnotic state." — Jean-Martin Charcot (January 1890).[22]

- "[Unlike Liébeault and Bernheim] Charcot never personally hypnotized any subject. The younger physicians worked with the subjects, and Charcot used them as demonstration subjects after they had learned what was expected of them and had seen other subjects perform. They were unwittingly trained by the physicians and by each other." — Frank Pattie (1967).[23]

- "One point that to me appears to be established by incontestable observations, is that the persons, whether men or women, who are susceptible of hypnotization, are nervous creatures, capable of becoming hysterical, if not actually hysterical at the beginning of the experiments. ... The training of the subjects is no easy thing and takes time; and besides, fit subjects are by no means so plentiful as some authors would have us believe." — Jean-Martin Charcot (April 1890).[24]

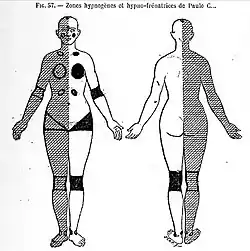

The "Hysteria School", or "Salpêtrière School", was centred on the theories and practices of Jean-Martin Charcot, a neurologist at the Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital in Paris, that were delivered upon a small, limited number of the female "hysteria" inpatients of the Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital — as "hysteria" was understood at the time[25][26] — which held, given its experimental subjects were all "hysteria" patients, perhaps mistaking correlation for causation, that "hypnosis" was a pathological state similar to hysteria.[27] The means of induction employed by Charcot's assistants included Braid's upwards and inwards squint, as well as wide range of auditory and tactile stimuli:[28]

- "[In relation to the means of hypnotization] Charcot's school at La Salpetiere has modified the Braid method, by placing pieces of glass close to the bridge of the nose, by which procedure the convergency of the eyes is increased and sleep comes more rapidly. A blow on a gong or a pressure on some "hypnogenic or hysterogenic" zone — such as an ovary, the top of the head, etc. (see: The "zones" of Albert Pitres) — or the app[r]oaching of a magnet will act on hysterical women." — Fredrik Johan Björnström (1887).[29]

Liégeois, hypnotism and suggestion

- "In this initial period ... Liégeois [rather than Bernheim] was the early worker, the most steadfast, the most militant, the most convinced [by Liébeault's work and "new method"]. He brought to the common cause the support of his moral authority, his character, his robust and active faith, which never wavered for a moment, and thanks to him, criminal legislation had to recognize and would increasingly deal with the phenomena of hypnotism and suggestion." — Henri-Étienne Beaunis (1909).[30]

- "Professor Liégeois's career ... is well known. I will confine myself to proclaiming, once again, that he was a true initiator. He was, in fact, the first to address the study of the relationship between hypnotism and law and jurisprudence. His studies were pushed so far in this direction that his name dominates the entire forensic study of hypnotism. It was in this capacity that he was called to the first international congress on hypnotism, in 1889, through his position as vice-president, to represent the legal experts. At the second congress, in 1900, he shared this honour with Mr. [Edmond] Melcot, Attorney General at the Court of Cassation ... [Admired for] his courage, energy, generosity, firmness in his carefully considered opinions, and consistency in his friendships ... his name will remain, in the history of hypnotism and psychology, indissolubly linked to that of Liébeault, with whom he was a faithful collaborator and to whom he brought, until the end, the comfort of his friendship." — Edgar Bérillion (1910).[31]

Despite being neither medical practitioner nor neurologist,[32] Liégeois was far better known than Bernheim, or Beaunis, or Liébeault at the time of his five (April/May 1884) lectures to the French Academy of Moral and Political Sciences on hypnotism, suggestion, and crime, and their subsequent publication (Liégeois, 1884). He was also becoming increasingly recognized as a significant French authority on hypnotism and hypnotic suggestion;[33] for instance, by August 1884 Le Monde illustré was referring to Liégeois as "the esteemed hypnotizing professor" ("L'estimable professeur hypnotisant").[34]

Suggestion

Although Liégeois' initial experiments reflected his academic interest in the legal parallels between hypnotism and natural/spontaneous (i.e., rather than "mesmeric" or "artificially induced") somnambulism,[35] his major work over an extended period involved a thorough investigation into the principles and practices responsible for a far wider range of applications of "suggestion" — both 'waking' suggestion and 'hypnotic' suggestion[36] — than their medical and/or therapeutic applications alone (i.e., Benheim's "suggestive therapeutics");[37] and, in particular, in addition to his interest in the phenomena produced by "suggestion", he was also interested in the nature, form, and content of the "suggestions" made.

Liégeois conducted experiments in which subjects displayed responses to suggestions made at a distance in time (1886e) and at a distance in space (1886b, 1886c). He confirmed (1886e) the existence of what Berhheim described as les suggestions post hypnotiques à longue échéance ('post-hypnotic suggestions to be realised after a long interval'),[38] when one of his subjects demonstrated a suggested result precisely 365 days (as demanded by Liégeois) after the relevant hypnotic suggestion had been delivered.[39] He also demonstrated that subjects could be hypnotised, and would respond to suggestions delivered to them over the telephone: and, in his report (1886b, p. 142; 1886c, p. 24), Liégeois supposed that a similar outcome might be achieved by a phonograph recording.[40][41]

Hallucinations

French alienist Jacques-Joseph Moreau's (1845) Du Hachisch et de l'aliénation mentale, which spoke of the hallucinations induced by drugs (e.g., opium, hashish) in otherwise "normal" people, had begun to shift disciplinary consciousness away from the view that, "because hallucination was a verifiable feature of the behaviour of the insane, the phenomenon must in itself be pathological" (Finn, 2017, p. 22), towards one that accepted that a capacity to experience hallucination was a feature of an entirely normal "existence intérieure" ('inner/subjective existence') and an entirely normal "vie intrà-cérébrale" ('intracerebral life'):[42]

- "The hallucination ... encompasses all of the faculties of the mind; its only limits are those that nature has placed upon the activity of mental functions. In other words, all mental abilities can be hallucinated, and not just certain abilities, such as those connected with the perception, for example, of sounds or images." — Jacques-Joseph Moreau (1845).[43]

Liégeois devoted an entire chapter of his 1889 work to the experiences of himself and others in relation to those hallucinations induced by hypnotic suggestion;[44] namely, both:

- (a) "hallucinations positives", perception of some thing as being present in the absence of any related external stimulus; and

- (b) "hallucinations négatives", perception of some thing as absent in the presence of a specific, related external stimulus (i.e., the rationale behind the modern processes of hypnotic pain management).

Liégeois, hypnotism and crime

As an academic and jurist Liégeois was interested in "the subject of personality modification and its implications in law" (Marchetti, 2015, p. 81) and, in particular, the legal questions raised in relation to "culpability", for instance, in the case of M. Emile X—,[45] as it had been observed by Adrien Proust (father of Marcel Proust) the Inspector-General of the French Government Sanitary Service, and had been reported in the French press, "as to the possibility of anyone exercising such an influence over another person as to make him or her irresponsible for the acts committed under that influence, even though those acts may be crimes".[45] Liégeois was especially interested in the extent to which it was possible that (otherwise innocent) subjects could be induced, by means of hypnotic suggestion, to commit crimes, thefts, and even murders. Gauld (1992, p.497) characterizes these events as "hypnotic crimes": namely, crimes wherein the hypnotic subject was both the "victim" and the "agent" of the crime — with the suggestion-delivering operator, rather than the suggestion-complying subject, being the actual "criminal".[46][47][48][49]

- "[In the mid-1880s, in addition to concerns relating to the possibility] of rape under hypnotic sleep[50] ... another type of moral concern associated with hypnotism was gaining public attention abroad: the possibility of inciting people under hypnosis to commit criminal acts. It was Jules Liégeois, the French lawyer associated with the Nancy School of hypnotism, who in 1884 first pointed to this danger in a report for the French Academy of Moral and Political Sciences."[51] — Kaat Wils (2017).[52]

- "It is possible to suggest to a subject in a state of somnambulism fixed ideas, irresistible impulses, which he will obey on awaking with mathematical precision. The subject may be induced to write down promises, recognitions of debt, admissions and confessions, by which he may be grievously wronged. If arms are given to him, he may also be induced to commit any crime which is prompted by the experimenter. ... These facts show that the hypnotic subject may become the instrument of a terrible crime, the more terrible since, immediately after the act is accomplished, all may be forgotten — the crime, the impulse, and its instigator." — Alfred Binet and Charles Féré (1888).[53]

Liégeois' own experiments, relating to both serious and petty crimes, which employed a wide range of suggested "mock" activities involving fake weapons, fake poisons, etc. — i.e., "crimes expérimentaux" ('experimental crimes'), or "crimes de laboratoire" ('laboratory crimes), in place of "crimes véritable" ('real crimes')[54] — was work for which he was much admired by the experimental psychologist, Joseph Delbœuf (e.g., Delbœuf, 1892),[55] and much denigrated by Charcot's associate, Georges Gilles de la Tourette (e.g., Gilles de la Tourette, 1891b).[56] However, as Bogousslavsky, Walusinski & Veyrunes (2009, pp. 197-198) observe, Gilles de la Tourette's criticism was somewhat unfair: not only had Gilles de la Tourette (some time earlier) personally conducted similar "hypnotic murder" experiments involving fake pistols and mock poisons at the Salpêtrière, but he had also reported them in detail in his 1887 work.[57]

Notwithstanding the obvious fact that individuals, subjected to extended processes of incremental suggestion, can be induced to self-harm (e.g, Peoples Temple suicides in Guyana in 1978, Heaven's Gate suicides in California in 1997, etc.) or coerced to commit a crime, most advocates of "hypnotic crimes" also recognize that the successful demonstration of an "experimental crime" is not, in and of itself, sufficient proof of the existence of an analogous "real crime"; for instance:

- "It may be set down as an axiom in experimental hypnotism that no laboratory experiment conducted for the purpose of ascertaining whether suggestion can be successfully employed to induce an hypnotic subject to perpetrate a crime is of any evidential value whatever.

When a subject is hypnotized for that purpose he knows that he is among friends. He knows that they are law-abiding citizens who will take care that no harm shall result from the experiments about to be made. He generally knows that he is expected to carry out all suggestions that are made to him. He is very probably aware that he is expected to demonstrate the truth of the proposition that a criminal hypnotist can compel his subject to commit crime. Like all hypnotic subjects he is anxious to win applause — to create astonishment. In short, he knows that he is the central figure in a comedy or farce which is about to be played in the interests of "science", and he feels that he is the "scientist". The inevitable consequence is that he resolves to carry out every suggestion of the hypnotist, knowing that no harm can possibly result." — Thomson Jay Hudson, LL.D., Ph.D., (1895, emphasis in original)[58][59][60]

- "It may be set down as an axiom in experimental hypnotism that no laboratory experiment conducted for the purpose of ascertaining whether suggestion can be successfully employed to induce an hypnotic subject to perpetrate a crime is of any evidential value whatever.

Liégeois' investigations culminated in his (1889a) magnum opus, "On suggestion and somnambulism in their relation to jurisprudence and legal medicine" — based upon the experience and observations he had accumulated since his earlier, five full-session presentation to the Académie des Sciences Morales et Politiques in April and May 1884 (Liégeois, 1884) — which concentrated in great detail upon the legal implications of hypnotism, hypnotic phenomena, and hypnotic suggestion, arguing that, in cases of hypnotic crime, only the person who gave the suggestions was guilty and must be prosecuted and punished, whilst the (irresponsible) hypnotised person should be acquitted on the grounds that they were nothing more than "a simple instrument", just like the pistol that contains a bullet, or a vase that contains poison:[61] however, as Laurence & Perry (1988) observe, it must be stressed that those within the Nancy School "did not believe that everyone could fall victim of criminal suggestion", and held the view that "only deeply hypnotizable subjects ... were generally at risk".[62][63]

Gabrielle Bompard

In December 1890, Michel Eyraud, aged 47, and Gabrielle Bompard, aged 21, were jointly tried in Paris for the (July 1899) murder of Toussaint-Augustin Gouffé.[65][66][67][68] Eyraud guilt had soon been established; and, so, the remainder of the trial was entirely concerned with the part played by Bompard. Maitre Henri-Robert, Bompard's advocate, argued that she had been hypnotized by Eyraud, her co-accused; and therefore, as Eyraud's involuntary accomplice, she could not be held responsible for Gouffé’s murder:[69]

Prosecution

The two expert witnesses for the prosecution, Paul Brouardel, the eminent professor of forensics at the Faculté de Médecine de Paris, and Gilbert Ballet, Charcot's chef de clinique ('clinical head') at the Salpêtrière, gave evidence that, in their view, any such thing was impossible; and in an extensive (later) discussion of the matter, Georges Gilles de La Tourette, a former pupil of Brouardel and close associate of Charcot, published an extensive account of the matter (i.e., 1891a, and 1891b), "which denied all possibility of a violent act under hypnosis and by suggestion" (Walusinski, 2011, p. 76).[73]

Defence

Called upon as an expert witness for Bompard's defence as a representative of the Nancy School,[74] Liégeois produced extensive details of the numerous experiments that had satisfied both himself and his Nancy colleagues that crimes could be committed by (innocent) subjects under the influence of hypnotic suggestion. Noting that ever since 1888, in relation to the "theories of Nancy", Bernheim had theorised "from the physiological point of view", whilst he (Liégeois) had theorised from the "moral and judicial sense",[75] Liégeois delivered a four-hour (uninterrupted) opinion as an expert witness:

- "Dr. Liégeois of Nancy gave evidence at great length regarding the hypnotic theory put forward by Bompard and her counsel. He stated that he and his colleague, Dr. Bernheim, found that in a state of profound hypnotism there was a complete absence of will in the subject, and that any suggestion made by the hypnotiser passes into the subject and inspires him or her to action. He gave instances of hypnotic subjects being excited to commit thefts, to fire a pistol at a friend, &c. As regards the present case, he thought there was reason to believe that Bompard might have acted under hypnotic suggestion. The fact of her having passed the whole night near the body of a man who had been murdered suggested that she was under some secret influence. In view of the proofs given that she was readily hypnotisable, and his conviction that it was possible for Eyraud to have hypnotised her to act as his accomplice, he thought the jury could not ignore this theory." — The Lancet, 3 January 1891.[70]

In his address to the court, Liégeois stated that his numerous experiments had satisfied both Bernheim and himself that, "in a state of profound somnambulism or hypnotism there is a complete absence of will in the subject, and that any suggestion by the hypnotiser passes into the subject, and inspires him or her to actions".[76] On the grounds that "he considered it possible that she might have received suggestions of which she did not retain any recollection when she was awake", Liégeois complained that he had been refused pre-trial access to Bompard, hoping to hypnotize her "to see to what degree she was open to hypnotic suggestion" and, also, "in order to revive her recollection of the facts which occurred at the moment of the commission of the crime".[76]

Verdict

Although found guilty, Bompard was not sentenced to death, but was sentenced to 20 years in prison with hard labour, due to what were considered to be "extenuating circumstances".[70] Her accomplice, Eyraud, found "Guilty without extenuating circumstances",[77] was executed by guillotine on 3 February 1891.[78] Bompard was released from prison ten years later, in January 1901, "on account of her good conduct while in prison";[79][80] and, three years later, in June 1903, she was pardoned.[81]

Demonstration of hypnotic influence (1903)

In late 1903, at the request of her 1889 trial advocate, Maitre Henri-Robert, Liégeois conducted various experiments upon Gabrielle Bompard "in order to prove that she had committed the, crime while under the hypnotic influence of Eyraud, a theory [that Henri-Robert had] advanced unsuccessfully at the trial".[82] As result of his experiments, "an officer of the Department of Justice, who was present at the seance ... [said that he was convinced that in] the case of Gabrielle Bompard [there was a] genuine hypnotic irresponsibility of crime".[83]

- "Professor Liegeois ... [who] says that he has never met with so easy a [hypnotic] subject ... is convinced [from his experiments] that the woman was compelled to participate in the crime while under hypnotic influence ... [and] that there was a gross miscarriage of justice in condemning such a person for acts for which she was wholly irresponsible, and [he] intends reporting the results of his investigations to the Academy of Medicine." — Press report from London, 11 December 1903.[82]

Death

Jules Liégeois died when "he was run over and killed by a motor car before the eyes of his wife, with whom he was walking on a quiet country road"[84] in the thermal spa town of Bains-les-Bains on 14 August 1908.[85][86][87]

Recognition

Liégeois was highly regarded in his lifetime for his contributions to public and administrative law, and to political economy; and, despite not being a medical practitioner, he was widely respected for the rigorous nature of the investigations he conducted into the theory, practice, applications, and efficacy of hypnotic suggestion in general, and for the expert opinions he published on hypnotism and crime in particular.

- 1863: admitted as an Associate Member of the Académie de Stanislas on 23 January 1863.[88]

- 1874: admitted as a Full Member of the Académie de Stanislas on 27 March 1874.[88]

- 1881: admitted as a Full Member of the Society of Comparative Legislation in May 1881.[89]

- 1881-1882: served as President of the Académie de Stanislas.[90]

- 1886: made a Corresponding Member of the Society for Psychical Research.[91]

- 1889: appointed Vice-President of the First International Congress of Experimental and Therapeutic Hypnotism, in Paris, in August 1889.[92]

- c.1890: made an Honorary Member of the Gesellschaft Für Psychologische Forschung ('Society for Psychological Research').[93]

- 1897: appointed Honorary President of the International Congress of Neurology, Psychiatry, Medical Electricity, and Hypnology, in Brussels, in 1897.[94]

- 1899: made a Corresponding Member of the Académie des Sciences Morales et Politiques, the organization to which he had made a significant presentation in 1884.[86]

- 1900: appointed Vice-President of the Second International Congress of Experimental and Therapeutic Hypnotism, in Paris, in August 1900.[95]

- 1904: made a Chevalier (Knight) of the Légion d'honneur (Legion of Honour), by decree, on 26 July 1904.[96]

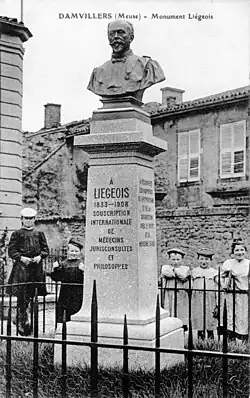

.jpg)

ion. Unveiled on 22 August 1909.

Memorials

- Bains-les-Bains (1909): A bronze bust of Jules Liégeois, created by the Nancy ceramist and sculptor Ernest Bussière (1863-1913) — a member of the other "Nancy School", the École de Nancy founded by the Art Nouveau artist and designer Émile Gallé — was erected on a granite pedestal designed by the architect Louis-Ernest Mougenot (1862-1929),[97] and was unveiled on 22 August 1909, in the park of the thermal establishment at which Liégeois had been a regular spa guest.[98][97] The monument was raised by international subscription.[99][100]

- As well as Liégeois's widow and son, the unveiling was attended by Professor Gaston Floquet of the Science Faculty at Nancy University and Vice-President of its Council; Dr. Auguste Mathieu, Director of the thermal spa; Dr. Faivre d'Arcier, of the spa's medical staff; and Professor Edgar Bérillon of l’École de Psychologie in Paris.[97] A last minute change in the date of the unveiling meant that a number of those who intended to be there were unable to attend.[101]

- Several of those who were able to attend also made speeches:[102]

Professor Gaston Floquet, from Nancy's Science Faculty.[103]

Dr. Albert van Renterghem (1845-1939), of Amsterdam, President of the monument's International Subscription Committee.[104]

Prof. Henri-Étienne Beaunis, the Nancy colleague of Liégeois.[105]

Louis Monal, President of the spa's Administrative Council.[106]

Professor Edgar Bérillon, of l’École de Psychologie.[107]

Albert Bonjean (1858-1939), an Advocate from Verviers, Belgium, Secretary to the monument's International Subscription Committee.[108]

Prof. Hippolyte Bernheim, the Nancy colleague of Liégeois.[109] - The inscription on the front of the pedestal, "À Liegeois 1833—1908 Souscription Internationale de Medecins Jurisconsultes et Philosophes", indicates that the international subscriptions had come from the medical, legal, and philosophical professions.[110] The inscription on the left-hand side of the pedestal reads "Fut un des fondateurs de l'Ecole Nancy Hypnotisme" ('Was one of the founders of the Nancy School of Hypnotism').

- Damvillers (1909). A bronze bust of Jules Liégeois, also by Bussière, was erected upon a granite pedestal in the public square of Damvillers, and unveiled on 24 October 1909. Also raised by international subscription.[111][112][99]

- The same inscription on the front of the pedestal, "À Liegeois 1833—1908 Souscription Internationale de Medecins Jurisconsultes et Philosophes", as that at Bains-les-Bains. The inscription on the right-hand side of the pedestal reads "À découvert les rapports de l'hypnotisme et de la suggestion avec le droit et la médecine légale" ('Discovered the connections between hypnotism and suggestion and law and forensic medicine').

- The bronze bust was removed and melted down by the Germans during their First World War occupation of Damvillers. A replica cast iron bust was re-installed in Danvillers in 1997.[113]

- Nancy (1909): A plaster version of the same bust, by Bussière, is on display in the reception rooms of the Faculty of Law at Nancy University.[114]

See also

- Actus reus – In criminal law, the "guilty act"

- Agency (philosophy) – Capacity of an actor to act in a given environment

- American Law Institute Model Penal Code Rule (ALI rule) – Guideline governing legal pleas of insanity

- Automatism (law) – Legal defence; the criminal was unaware of their actions during the crime

- Henri-Étienne Beaunis – French physiologist, psychologist, and founding member of the Nancy School of Hypnosis

- Hippolyte Bernheim – French physician, neurologist, and founding member of the Nancy School of Hypnosis

- Brainwashing – Systematic coercive persuasion

- Causality – How one process influences another

- Candy Jones – American fashion model and radio host (1925–1990)

- Confabulation – Recall of fabricated, misinterpreted or distorted memories

- Credulity – Willingness or ability to believe that a statement is true

- Culpability – Degree to which one is morally or legally responsible for a crime

- Durham rule – Guideline governing legal pleas of insanity

- Forensic psychology – Using psychological science to help answer legal questions

- Hypnosis – State of increased suggestibility

- Ideomotor phenomenon – Concept in hypnosis and psychological research

- Invasion of the Body Snatchers – 1956 horror film directed by Don Siegel

- Ambroise-Auguste Liébeault – French physician and founding member of the Nancy School of Hypnosis

- M'Naghten rules – Guideline governing legal pleas of insanity

- Mass suicide – Groups of people killing themselves together

- Medical jurisprudence – Branch of science and medicine

- Memory erasure – Selective artificial removal of memories or associations from the mind

- Mens rea – In criminal law, the "guilty mind"

- MKUltra – CIA program involving illegal experimentation on human test subjects (1953–1973)

- The Nancy School of Hypnosis – French school of psychotherapy from 1866

- Posthypnotic amnesia – Inability in hypnotic subjects to recall events that took place while under hypnosis

- R v Burgess (1991) – 1991 English legal appeal

- The Salpêtrière School of Hypnosis – French school of psychotherapy from 1882

- Somnambulism – Sleeping phenomenon combined with wakefulness

- Source misattribution – Misidentification during memory recall

- Suggestibility – Inclination to accept the suggestions of others

- Suggestion – Psychological process of guiding a person

- The Manchurian Candidate – 1959 novel by Richard Condon

Notes

- ^ Guilhermet (1909), p. 18: "Liégeois fut le premier légiste à s’étre occupé scientifiquement de la question médicale de l’hypnotisme".

- ^ Temple, 1989, p. 331.

- ^ Biographies Meusiennes (1912), p. CIII.

- ^ a b c d e f Touzeil-Divina (2024a).

- ^ Vapereau (1893).

- ^ The designation "Suggestion School" was given because those at Nancy felt that "hypnosis" was a product of "suggestion", in contrast to those at the Salpêtrière School, who felt it was a pathological condition, analogous to "hysteria"; in fact, both "Schools" were equally interested in what is known as "hypnotic suggestion".

- ^ The hypnotized subject's experience of involuntariness, or automatism (an essential feature of a subject's rated "hypnotizability"), indicates a loss of "control" — in that they have transferred the agency of their actions to another individual, the operator (Peter, 2024, p. 8).

- ^ See, for instance: Liégeois, 1884; Liégeois, 1889a; Liégeois, 1889b; Brodie-Innes, 1891; Gilles de la Tourette, 1891a; Gilles de la Tourette, 1891b; Delbœuf, 1892; Liégeois, 1898a; Barber, 1961; Murray, 1965; Orne & Evans, 1965; and Marchetti, 2015.

- ^ Unlike the case of mesmerism — where, almost without exception, every operator's manual speaks of the ideal spiritual, mental, moral, and physical "qualifications" of the mesmeric operator (e.g., Esdaile, 1846, pp. 11-14; Barth, 1850, pp. 83-86; Buckland, 1851, pp. 46-51; Davey, 1862, pp. 1-6; Coates, 1890, pp. 41-48; Randall, 1904, pp. 13-26, etc.) — Peters (2024) also notes that, despite the extensive research conducted into theoretical and practical variables of hypnotism over the last 150 years, "the therapist variable [of] "hypnotization ability", i.e., the ability to induce hypnosis convincingly and to work with explicit hypnotic phenomena, has not yet been researched at all" (p. 9).

- ^ Further, in relation to Braid's "hypnotism": "It has been a basic assumption of modern (i.e., twentieth century) hypnotism that it is founded on the same phenomenology it historically evolved from. Such differences as exist between older versions of hypnotism and newer ones being reduced largely to a matter of interpretation of the facts. That there are common elements is not in question, but that there is full identity in questionable and basically untestable" (Weitzenhoffer, 2000, p. 3; emphasis added).

- ^ Bernheim (1888), pp. 286-287; translation taken from Bernheim (1889), p. 203.

- ^ See: Carrer (2002).

- ^ a b c See Berheim's remarks at the 1909 unveiling of the Liégeois monument in Bains-les-Bains ("Homage", 1909), in which he spoke of Liégeois, himself, and Beaunis establishing the "triple control" of Liébeault's "new doctrine": namely, the "therapeutic, legal, and physiological control".

- ^ Nicolase & Ferrand (2002), p. 1.

- ^ Beaunis published his first work on the physiology of the brain and physiological psychology in 1884 (Beaunis, 1884).

He published a summary of his hypnotism-centred research within the Nancy group in 1886 (Beaunis, 1886). He believed that hypnotism offered a valuable experimental method for philosophers, the value of which was equal to that of vivisection to the physiologist ("L'hypnotisme constitue, en effet, ... une véritable méthode expérimentale; elle sera pour le philosophe ce que la vivisection est pour le physiologiste" (Beaunis, 1886, p. 115). - ^ See, for instance, "The Nancy School 1882-1892", at Gauld (1992, pp. 319-362); and also Klein (2010).

- ^ Nicolas & Ferrand (2002), p. 2.

- ^ According to Serge Nicolas, who had access to parts of Beaunis' Mémoires, Beaunis had stressed "that Liebault, Bernheim, Liegeois, and himself agreed on only two points. The first point concerned the unreality of the phenomenon described by Jean-Martin Charcot (1825-1893) and the school of the Salpêtrière. This phenomenon was due only to unconscious suggestion. The second point concerned the great powers of suggestion and its use in therapeutics. They disagreed on all other points." (Nicolas & Ferrand, 2002, p. 2).

- ^ Plate XX, facing page 204 in Bourneville and Regnard (1880).

- ^ Pitres (1891), p. 499.

- ^ "It seems plain that, however valuable such studies may be from a pathological point of view, they can have little to do with the normal conditions of hypnosis, and we think that more than due importance has been attached to them" (Vincent, 1897, p. 94).

- ^ Charcot (1890a), p. 36.

- ^ Pattie (1967), p. 36.

- ^ Charcot (1890b), pp. 160, 163.

- ^ Gordon, et al. (1984).

- ^ Bogousslavsky (2020).

- ^ According to George Owen (1971, p. 211) at the time of his death (1893), Charcot was preparing to retract his view, in favour of the Nancy position.

- ^ See: Pesic (2022), and Raz (2023).

- ^ Björnström (1887), p. 16.

- ^ The remarks of Henri-Étienne Beaunis, one of the four "founders" of the Nancy School, at the 1909 unveiling of the Liégeois monument in Bains-les-Bains (Beaunis (1909), p. 70).

- ^ The remarks of Edgar Bérillion, in his address to the Tenth Opening Ceremony of L'Ecole de psychologie in Paris on 10 January 1910 (Bérillion, 1910, pp.229-230).

- ^ The issue of Liégeois' "outlier" non-medical profession was constantly raised in the ad hominem attacks made over the years by those seeking to belittle his research, theories, and influence.

For instance, Georges Gilles de la Tourette, in his response to Liégeois' presentation to the First International Congress of Experimental and Therapeutic Hypnotism (Liégeois, 1889b) on the dangers of criminal suggestions, expressed his disappointment (Bérillion, 1889, p. 264) that Liégeois, a Professor of Law, had not confined his presentation to the legal issues of the relationship between hypnotism and jurisprudence/forensic medicine, and had chosen, instead, to speak of a wide range of medical and physiological aspects of hypnotism. - ^ "Professor Beaunis said of [Liégeois] that of all the authors who have investigated hypnotic phenomena none has drawn a picture of such extraordinary clearness and exactitude." (Tuckey (1909), p. 31.

- ^ "Courrier de Paris" ('Paris Courier'), Le Monde illustré, (16 August 1884), p. 98.

- ^ For an historical account of sleepwalking and the law, see Umanath, et al. (2011): and, in relation to on-going (21st-century) legal issues, see "sleep" and "legal automatism", "sleepwalking" as a legal defense, and, for instance Regina v Burgess 1991.

- ^ That is, the directives delivered by an operator to a "hypnotized" subject. This is quite different from Benheim's major research question: that of "suggested hypnosis" — the question of whether or not the "hypnosis" produced by Bernheim's dormez, dormez, dormez induction, was "suggested", rather than (as was the case of James Braid's upwards and inwards squint induced "hypnotism") being due to a Cartesian-reflex.

- ^ Effects of Mesmerism: Hypnotism and Crime: Remarkable Experiments Made by a French Scientist: An Important Problem in Medical Jurisprudence — Tests Applied to a French Lady and a Soldier — Result of the Experiments, The Nepean Times, (Saturday, 19 January 1889), p. 2.

- ^ Namely, those suggestions which are (i) intended "to produce a particular effect at a designated later hour", (ii) have "no influence before the appointed hour", (iii) nor "after it had expired" (Barrows, 1896, pp. 22-23).

- ^ For details of similar experiments by others, see Newbold (1896).

- ^ In a similar vein, four years later, during a series of demonstrations of hypnotic anæsthesia (in one case involving the removal of 16 teeth) to a group of medical and dental men at Leeds in March 1890, the Scots surgeon John Milne Bramwell demonstrated the induction of hypnotism and the delivery of suggestion by letter (Anon, 1890a; Anon, 1890b).

- ^ In his presentation to the Second International Congress of Experimental and Therapeutic Hypnosis of 1900, the Paris physician Hippolyte Baraduc reported his wax-cylinder-phonographic-recording-alone induction of hypnosis, and his successful use of wax-cylinder-phonographic-recorded-suggestions-alone in the treatment of a dozen different patients, in his efforts to test the "intrinsic value" (la valeur intrinsèque) of suggestion in itself, by eliminating any "question" of the possible longer-term influence of a relationship being created between the hypnotic-subject (le suggestionné) and the hypnotic-operator (le suggestionneur) — and, thus, testing the form and content of the suggestive sequence delivered in this fashion (Baraduc, 1902).

- ^ Moreau, 1845,p. 168.

- ^ Moreau, 1845, p. 168 (trans. from Moreau, 1973, pp.84-85).

- ^ "Les Effets Pychologiques: Les hallucinations — L'amnésie" ('Pychological Effects: Hallucinations — Amnesia') (Liégeois, 1889a, pp. 307-354).

- ^ a b Story of "Double Existence", The Queenslander, (Saturday, 3 May 1890), p. 851.

- ^ In relation to the issue of "the hypnotized as an offender and [as] an accused", neurologist Joseph Grasset observed that "at such times his responsibility is palliated, or annihilated, and should be transferred to the hypnotist." (Grasset, 1910, p. 70; emphasis added to original).

- ^ In relation to Liégeois (1889), Leaf's positive (contemporaneous) review concluded that "no student of hypnotism can afford to neglect this important work" (Leaf, Walter (1889), "Professor Liégeois on Suggestion and Somnambulism in Relation to Jurisprudence", Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research, Vol.6, Supplement, (July 1889), pp. 222-224).

- ^ For a summary of the wide range of early investigations into the possible influence of hypnotism and crime see Gauld (1992), pp.494-503; also Innes (1890).

- ^ See, also, Bell (1898) for a wide range of US medico-legal opinions at the time, including those addressing the question of whether hypnotism and hypnotic suggestion could be accepted as an objective scientific (let alone legal) fact.

- ^ Wherein the hypnotized, physically unable-to-respond, sexually assaulted individual was the "victim" of a criminal act (i.e., the site of the "crime"), rather than being the "perpetrator" of a criminal act, such as shooting, that they performed upon another (i.e., the agent of the "crime").

- ^ Namely, Liégeois (1884): Liégeois' five full-session presentations, "On hypnotic suggestion in its relation to civil and criminal law", made to to the Académie des Sciences Morales et Politiques, on 5, 9, and 26 April, and 3 and 10 May 1884.

- ^ Wils (2017), pp 181-182.

- ^ Binet and Féré (1888), p. 372.

- ^ For more contemporaneous discussions on these medico-legal issues of experimental vs. real crimes, see: Hudson, 1895a (Hudson was both a lawyer and a proficient and experienced hypnotist); Howard, 1895; Hudson, 1895b; Bell, 1898; and Sudduth, 1898.

- ^ According to Delbœuf, who had visited Liégeois at Nancy and observed his experiments at first hand, no-one could have conducted the experiments better than Liégeois had; however, Delbœuf also noted that Liégeois' experiments possessed the "irremediable flaw" (tort irrémédiable) of being "necessarily simulated" (d'être forcément simulées).

- ^ Touzeil-Divina (2024b).

- ^ Namely, having hysteria patient "E. H..." use a ruler to "shoot" and kill one of the hospital's interns, Mr. "B...", and having hysteria patient Marie "Blanche" Wittman "poison" Mr. "G...": at "Les suggestions dites Criminelles" ('The so-called Criminal Suggestions') at (1887, pp.129-136).

- ^ Hudson (1895a), p. 108.

- ^ The same view, derived from his own empirical experience, was expressed by Martin Orne, almost seventy years later:

"[Given that] the laboratory hypnotist is generally known by the subject to be a reputable investigator who will undoubtedly ensure the safety of all involved despite the appearance of the situation ... [and, given that] volunteer subjects are often motivated to tolerate dangerous and stressful situations for the sake of advancing scientific knowledge ... no situation which is perceived by the subject to be a scientific experiment can validly test the question of the possibility of hypnotically inducing antisocial behavior." (Orne, 1960, p. 133.] - ^ A contemporary of Liégeois and Hudson, the Braid scholar and experienced hypnotherapeutic practitioner, John Milne Bramwell, noted that, whilst "automatism, cannot be regarded as the essential characteristic of the hypnotic state", and despite the fact that he (Bramwell) "[had] never seen a single hypnotic somnambule who did not both possess and exercise the power of resisting suggestions contrary to his moral sense", he could "conceive the possibility that, under certain circumstances, hurtful suggestions might be made with success", "if a subject believed that hypnosis was a condition of helpless automatism, and that the operator could make him do whatever he liked, harm might result, not through the operator's power, but in consequence of the subject's self-suggestions." (1903, p.425, emphasis added to original).

- ^ Liégeois, 1889, §.157, pp. 129-130.

- ^ Laurence & Perry (1988), p. 225; emphasis in original.

- ^ Beyond the same sorts of medico-legal issues that were being addressed by the French courts (c.1850s) centred on the practice of "animal magnetism" by those outside the medical community — viz., "magnetism as an illegal practice of medicine, magnetism as fraud, and the potential abuse of magnetism to commit criminal acts" (Laurence & Perry, 1988, p. 156) — for a more detailed understanding of the legal issues connected with other aspects of the modern practice of hypnotism and suggestion (and "experimental crimes") in relation to not only crimes committed upon hypnotized subjects (e.g., Temple, 1989, pp.254-274), and those committed by hypnotized subjects (e.g., Temple, 1989, pp.148-253), but also to the wider ("malpractice/malfeasance") medico-legal issues relating to the hypnotism-centred creation of false memories per medium of "recovered-memory therapy", "past life regression", "Satanic Ritual abuse", etc., as well as the issues of the veracity of hypnotism-assisted witness testimony (see: Diamond, 1980), and the extent to which hypnotism may or may not be a productive forensic tool, see Laurence & Perry (1988) passim, Scheflin & Shapiro (1989) passim, and Temple (1989), pp.147-357.

- ^ Penal Code of France (1819), p. 14.

- ^ The Eyraud-Bompard Trial: Conviction of Gouffe's Murderers: The Story of a Strange Crime, The (Adelaide) Express and Telegraph, (Saturday, 31 January 1891), p. 2.

- ^ Sims, 1921.

- ^ Hardy, 1950.

- ^ Irving (1918).

- ^ In a similar case, Thomas Patten was murdered by his farmhand, Thomas E. McDonald, in Winfield, Kansas on 5 May 1894. Anderson Gray — who had hypnotised McDonald, and compelled McDonald per medium of hypnotic suggestion to murder Patten — was found guilty, and McDonald was acquitted (Appealed: Hypnotic Case will go to Supreme Court, The Hutchison (Kansas) News, 31 December 1894, p. 1). Gray unsuccessfully appealed, and was sentenced to death for instigating Patten's murder (see: "Hypnotism not a Factor"; "Post-Hypnotic Responsibility"; and Ladd (1902)). In January 1897, Edmund N. Morrill, the Governor of Kansas, pardoned Gray (see: "Pardoned a Hypnotist").

- ^ a b c The Eyraud-Bompard Trial in France, The Lancet, Vol.1, No.3514, (3 January 1891), pp. 35-37.

- ^ As Marchetti (2015) observes: "Among legal scholars, the idea of the existence of different psychological forces which were not controlled by a person, whether healthy or ill, could not be easily accepted. Medicine and law were only able to speak the same language if they made reference to an identical view of the human being." (p. 88)

- ^ Moreover, as Marchetti (2015) also observes: "the discovery of a new unconscious dimension in the psychological activity in human beings inevitably collided with the view of a person who is able to determine his own actions with consciousness, to whom law, in its punitive claim, had always made reference." (p. 89)

- ^ In 1893, three years after Bompard's trial, Gilles de la Tourette himself was really shot in the neck three times by Rose Kamper-Lecoq, his former patient, who claimed that she acted under the influence of hypnosis that had been induced, against her will, by one of his colleagues.

- ^ Liégeois' on-going emphasis on both himself and Bernheim holding the same opinions is easily explained: Liégeois was a substitute for Bernheim, who could not attend because he had a broken leg (Bogousslavsky, Walusinski & Veyrunes, 2009, p. 197).

- ^ The Gouffe Murder Trial, The Brisbane Courier, (Wednesday, 4 February 1891), p. 7.

- ^ a b "The Gouffe Murder Trial", The Queenslander, (Saturday, 14 February 1891), pp. 325—326.

- ^ "Hypnotism and Murder".

- ^ Romance of Crime: The Last French Murder: History of a Guillotined Man, The (Sydney) Evening News, (Saturday, 7 February 1891), p. 3.

- ^ French Cause Celebre: The Murder of Gouffe: Gabrielle Bompard Released, The Argus, (Monday, 21 January 1901), p. 5.

- ^ Fortunate Murderess: Release from Gaol, The (Brisbane) Telegraph, (Saturday, 9 February 1901), p. 7.

- ^ French Tragedy: A Pardon Granted, The West Australian, (Wednesday, 10 June 1903), p.7.

- ^ a b "Detection by Hypnotism: A Murder Rehearsed", The (Adelaide) Advertiser, (Wednesday, 13 January 1904), p. 6.

- ^ The Story of an Hypnotic Crime, The (Perth) Daily News, (Tuesday, 5 July 1904), p. 6.

- ^ Tuckey (1909), p. 31.

- ^ Obituary: Death of Professor Liégeois, Journal of the American Medical Association, Vol.51, No.11, (12 September 1908), p. 929.

- ^ a b de Foville (1908).

- ^ Guilhermet (1909).

- ^ a b "Membres Titulaires", Mémoires de l'Académie de Stanislas (1878), Vol.4, No.9 (1879), p. 443.

- ^ "Séance du 11 Mai 1881" ('Meeting of 11 May 1881'), Bulletin de la Société de législation comparée,Vol.17, No.6, (June 1881), p. 394.

- ^ "Liste des présidents de de l'Académie de Stanislas", academie-stanislas.org.

- ^ "New Members and Associates: Corresponding Members", Journal of the Society for Psychical Research, Vol.2, No.34, (November 1886), p. 441.

- ^ Bérillion (1889), p. 6.

- ^ Sommer (2013), p. 33.

- ^ "Présidents d'Honneur", p.15, in Crocq Jean (1898), Congrès International de Neurologie, de Psychiatrie, d'Electricité Médicale et d'Hypnologie: Premiére Session tenue a Bruxelles du 14 au 21 Septembre 1897: Fascicule I: Rapports, Paris: Félix Alcan.

- ^ "Vice-présidents", p. 22 in Bérillon, Edgar and Farez, Paul (1902), Deuxième congrès international de l'hypnotisme expérimental et thérapeutic tenu à Paris du 12 au 18 Août 1902 (sic), Paris: Revue de L'hypnotisme, 1902.

- ^ Légion d'honneur Registration no.69,280, Archives Nationales: Ministère de la culture - Base Léonore.

- ^ a b c "Inauguration" (1909a), p. 65.

- ^ "Monuments aux Grands Hommes: Monument à Jules Liégeois – Bains-les-Bains" ('Monuments to Great Men: Monument to Jules Liégeois – Bains-les-Bains'), e-monumen.net.

- ^ a b Bérillion (1910).

- ^ For a list of the French and foreign scholars that formed the International Subscription Committee, see: "Bulletin", Revue de l'Hypnotisme et de la Psychologie Physiologique, Vol.24, No.1, (July 1909), p. 1.

- ^ Those unable to attend included Charles Adam (1857-1940), the Rector of Nancy University; Dr. Jules Voisin (1844-1920), the President of the Société d'hypnologie et de psychologie, who, in 1890, as Prison doctor, had hypnotised Gabrielle Bompard; Profs. Paul Magnin, Paul Faraz, and Henry Lemesle of l’École de Psychologie; and Dr. Witry, of Trèves-sur-Moselle, and Dr Stavros Constantine Damoglou, of Cairo, Corresponding Professors of l’École de Psychologie ("Inauguration", 1909a, p. 65).

- ^ "Inauguration", 1909a; "Homage", 1909.

- ^ Floquet (1909).

- ^ van Renterghem (1909).

- ^ Beaunis (1909).

- ^ Monal (1909).

- ^ Bérillion (1909).

- ^ Bonjean (1909a); he was also a researcher of hypnotism, suggestion, hypnotism and crime (Bonjean, 1909b).

- ^ "Homage" (1909).

- ^ See, for instance, the Polish equivalent of the French Jurisconsulte at Legal advisor (Poland)).

- ^ Monument to Professor Liégeois, Journal of the American Medical Association, Vol.53, No.21, (29 November 1909), p. 1754.

- ^ "Inauguration" (1909b).

- ^ "Monuments aux Grands Hommes: Monument à Jules Liégeois – Damvillers (remplacé)" ('Monuments to Great Men: Monument to Jules Liégeois – Damvillers (replaced)'), e-monumen.net.

- ^ For a photograph of the bust see Touzeil-Divina (2024a).

References

Jules Liégeois

- 1858: De la Liberté de l'intérêt ('On the Freedom of Interest'), Nancy: Grimblot.

- 1861: Du Prêt à intérêt, en droit romain et en droit français ('Interest-bearing loans in Roman law and French law'), Nancy: A. Lepage.

- 1863: Essai sur l'histoire et la legislation de l'usure ('Essay on the History and Legislation of Usury'), Paris: August Durand., Paris: August Durand.

- 1865: Des Rapports de l'économie politique avec le droit public et administratif ('On the Relationship of Political Economy with Public and Administrative Law'), Paris: A. Marescq aîné.

- 1867: Des Attributions des conseils généraux, ou Explication pratique de la loi du 18 juillet 1866: Seconde édition, augmentée d'un Appendice contenant la circulaire de M. le ministre de l'Intérieur du 29 juillet 1867 ('Powers of the General Councils, or Practical Explanation of the Law of July 18, 1866: Second Edition, augmented by an Appendix containing the circular of the Minister of the Interior of July 29, 1867'), Nancy: N. Collin.

- 1873a: "Origines et théories économiques de l’Association internationale des travailleurs (Nancy, 14 Decembre 1871)" ('Origins and economic theories of the International Workingmen's Association'), Mémoires de l'Académie de Stanislas (1872), Vol.4, No.5 (1873), pp. 1-55.

- 1873b: (with Louis Cabantous) Répétitions écrites sur le droit administratif: contenant l'exposé des principes généraux, leurs motifs et la solution des questions théoriques (Cinquième édition), ('Written Reviews on Administrative Law: Containing the Statement of General Principles, Their Reasons and the Solution of Theoretical Questions (Fifth Edition)'), Paris: A. Marescq Ainé.

- 1873c: De l'organisation départementale; ou, Commentaire de la loi du 10 août 1871 sur l'organisation et les attributions des conseils généraux et des commissions départementales, ('On the departmental organization; or, Commentary on the law of August 10, 1871 on the organization and attributions of the general councils and departmental commissions'), Paris: A. Marescq Ainé.

- 1877: "La Monnaie et le billet de banque (Séance Publique du 24 mai 1877)" ('Money and the Banknote (Public Session of May 24, 1877)'), Mémoires de l'Académie de Stanislas (1876), Vol.4, No.9 (1877), pp. XXXVII-LIX.

- 1878: Le Code civil et les droits des époux en matière de succession ('The Civil Code and the rights of spouses in matters of inheritance'), Paris: Berger-Levrault et Cie.

- 1879: Le Code civil et les droits des époux en matière de succession ('The Civil Code and the rights of spouses in matters of inheritance'), Mémoires de l'Académie de Stanislas (1878), Vol.4, No.11 (1879), pp. 95-130.

- 1881a: "Projet de création d’une caisse de prévoyance des fonctionnaires civils" ('Project for the Creation of a Civil Servants' Provident Fund'), Revue Générale d’Administration (Janvier-Avril 1881), Vol.7, (1 January 1881), pp. 5-25.

- 1881b: Le Tarif des douanes et le prix du blé ('The Customs Tariff and the Price of Wheat'), Nancy: Imprimerie Berger-Levrault et Cie.

- 1882a: "La Question Monétaire, ses Origines et son État actuel", ('The Monetary Question, its Origins and its Current State', Mémoires de l'Académie de Stanislas (1881), Vol.4, No.14 (1882), pp. 168-203.

- 1882b: "Le Tarif des douanes et le prix du blé" ('The Customs Tariff and the Price of Wheat'), Mémoires de l'Académie de Stanislas (1881), Vol.4, No.14 (1882), pp. 204-243.

- 1882c: (with Louis Cabantous) Répétitions écrites sur le droit administratif: contenant l'exposé des principes généraux, leurs motifs et la solution des questions théoriques (Sixième édition), ('Written Reviews on Administrative Law: Containing the Statement of General Principles, Their Reasons and the Solution of Theoretical Questions (Sixth Edition)'), Paris: A. Marescq Ainé.

- 1883: ("Au nom du Groupe de Nancy, Le President, Jules Liégeois, Nancy, le 20 mai 1883") "Lettre adressée à M. le Président du Conseil, Ministre de l’Instruction publique et des Beaux-Arts, à propos du projet de modification de la loi militaire" ('Letter Addressed to the President of the Council, Minister of Public Instruction and Fine Arts, Regarding the Draft Amendment to Military Law'), Revue Internationale de l'Enseignement Publiée par la Société de l'Enseignement supérieur ; 1883, Vol.5, pp. 666-672.

- 1884: De la suggestion hypnotique dans ses rapports avec le droit civil et le droit criminel: Mémoire lu à l'Académie des sciences morales et politiques (séances des 5, 19, 26 avril, 3 et 10 mai 1884) ('On hypnotic suggestion in its relation to civil and criminal law: Dissertation read to the Academy of Moral and Political Sciences (sessions of April 5, 19, 26, May 3 and 10, 1884)'), Paris: Alphonse Picard.

- 1886a: "Note: Vésication par suggestion hypnotique" ('Blistering by hypnotic suggestion'), Mémoires de l'Académie de Stanislas (1885), Vol.5, No.3 (1886), pp. 126-132.

- 1886b: "Note: Hypnotisme Téléphonique: Suggestions a grande distance" ('Telephonic hypnotism: Long distance suggestions'), Mémoires de l'Académie de Stanislas (1885), Vol.5, No.3 (1886), pp. 133-142.

- 1886c: "Hypnotisme Téléphonique — Suggestions a grande distance" ('Telephonic hypnotism — Long distance suggestions'), Revue de l'Hypnotisme Expérimental & Thérapeutique, Vol.1, No.1, (July 1886), pp. 19-24.

- 1886d: "De l'hypnotisme au point de vue médico-légal" ('Hypnotism from a medico-legal point of view'), Journal des Débats Politiques et Littéraires, 24 August 1886.

- 1886e: "Une suggestion à 365 jours" ('A 365-day suggestion'), Journal des Débats Politiques et Littéraires, 1 November 1886.

- 1888a: "De la Suggestion et du Somnabulisme dans leurs Rapports avec Jurisprudence et la Médecine Légale" ('On Suggestion and Somnabulism in their Relations with Jurisprudence and Legal Medicine'), Revue de l'Hypnotisme et de la Psychologie Physiologique, Vol.2, No.12, (June 1888), pp. 356-359.

- 1888b: "Des expertises médico-légales en matière d'hypnotisme: Recherche de l'auteur d'une suggestion criminelle" ('Medico-legal examinations in hypnotism: search for the author of a criminal suggestion'), Revue de l'hypnotisme et de la Psychologie Physiologique, Vol.3, No.1, (July 1888), pp. 3-8.

- 1888c: "Un nouvel état psychologique" ('A new psychological state'), Revue de l'Hypnotisme et de la Psychologie Physiologique, Vol.3, No.2, (August 1888), pp. 33-49.

- 1889a: De la Suggestion et du Somnambulisme dans leurs Rapports avec la Jurisprudence et la Médecine Légale ('On Suggestion and Somnambulism in their Relations with Jurisprudence and Legal Medicine'), Paris: Octave Doin.

- 1889b: "Rapports de la Suggestion et du Somnambulisme avec la Jurisprudence et la Médecine Légale — La responsabilité dans les états hypnotiques" ('Relationships between Suggestion and Somnambulism and Jurisprudence and Forensic Medicine — Responsibility in Hypnotic States"'), pp 244-278 in Bérillion, Edgar (ed.), Premier Congrès International de l’Hypnotisme Expérimental et Thérapeutique: Tenu à l'Hôtel-Dieu de Paris, du 8 au 12 Août 1889 ('First International Congress of Experimental and Therapeutic Hypnotism: Held at the Hôtel-Dieu in Paris, from August 8 to 12, 1889'), Paris: Octave Doin.

- 1890a: "Les coalitions de producteurs, les accaparements de stocks et l'article 419 du code pénal" ('Producer coalitions, stock hoarding and Article 419 of the Penal Code'), Mémoires de l'Académie de Stanislas (1889), Vol.5, No.7 (1890), pp. 394-438.

- 1890b: "J. Delbœuf. Le magnétisme animal. A propos d'une visite à l'École de Nancy (Book Review), Revue Philosophique de la France et de l'Étranger, Vol.29, (March 1890), pp. 314-319. JSTOR 41075212

- 1892a: "Hypnotisme et Criminalité" ('Hypnotism and Crime'), Revue Philosophique de la France et de l'Étranger, Vol.33, (January—June 1892), pp. 233-272. JSTOR 41075390

- 1892b: "L’Hypnotisme, la défense nationale et la société civile" ('Hypnotism, National Defence and Civil Society'), Revue de l'hypnotisme et de la Psychologie Physiologique (1891-1892), Vol.6, (1892), pp. 298-304.

- 1893: "Der Fall Chambige vor dem Schwurgerichtshof in Constantine (Algier) 1888. Eine Studie zur criminellen Psychologie" ('The Chambige Case before the Assize Court in Constantine (Algiers) 1888. A Study in Criminal Psychology'), Zeitschrift für Hypnotismus, Suggestionstherapie, Suggestionslehre und verwandte psychologische Forschungen, Vol 1, No.6, (April 1893), pp. 212-216, Vol 1, No.7, (April 1893), pp. 234-238.

- 1894: "L’affaire Chambige (étude de psychologie criminelle)" ('The Chambige Affair (study of criminal psychology)'), Revue de l'Hypnotisme et de la Psychologie Physiologique, Vol.8, No.8, (February 1894), pp. 234-240.

- 1897: "La question des suggestions criminelles: ses origines — son état actuel" ('The Question of Criminal Suggestions: Its Origins — Its Current State'), Revue de l'Hypnotisme et de la Psychologie Physiologique, Vol.12, No.4, (October 1897), pp. 97-104.

- 1898a: "L'hypnotisme et les Suggestions Criminelles" ('Hypnotism and Criminal Suggestion'), Reports: Congrès International de Neurologie, de Psychiatrie, d'Electricité médicale & d'Hypnologie (Première Session: Tenue a Bruxelles du 14 Au au 21 Septembre 1897), Fas.1, (17 Septembre 1897), pp.191-224.

- 1898b: "La question des suggestions criminelles: ses origines — son état actuel" ('The Question of Criminal Suggestions: Its Origins — Its Current State'), Journal de Neurologie, Vol.3, No.2, pp 22-49.

- 1898c: "Les suggestions hypnotiques criminelles: dangers et remedies" ('Criminal Hypnotic Suggestions: Dangers and Remedies'), Revue de l'Hypnotisme et de la Psychologie Physiologique, Vol.12, No.7, (January 1898), pp. 203-211; No.8, (February 1898), pp. 236-243; No.9, (March 1898), pp. 273-279; No.10, (April 1898), pp. 311-318.

Others

- Anon (1890a), "Demonstration of Hypnotism as an Anæsthetic during the Performance of Dental and Surgical Operations", The Lancet, Vol.135, No.3475, (5 April 1890), pp. 771-772.

- Anon (1890b), "Hypnotism as an Anæsthetic in Surgery", The British Medical Journal, No.1528, (12 April 1890), pp. 849-850.

- Baraduc, Hippolyte (1902), "La Suggestion Phonographique" ('Phonographic Suggestion', delivered to the Sixth Session of the Congress, 17 August 1900), pp. 231-233 in Bérillon, Edgar and Farez, Paul (1902), Deuxième congrès international de l'hypnotisme expérimental et thérapeutic tenu à Paris du 12 au 18 Août 1902 (sic), Paris: Revue de L'hypnotisme, 1902.

- Barber, Theodore X. (1961), "Antisocial and Criminal Acts induced by "Hypnosis": A Review of Experimental and Clinical Findings". Archives of General Psychiatry, Vol.5, No.3, (September 1961), pp. 301-312. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710150083013

- Barrows, Charles Mason (1896), "Suggestion Without Hypnotism: An Account of Experiments in Preventing or Suppressing Pain", Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research, Vol.12, No.30, pp. 21-44.

- Barth, George H. (1850), The Mesmerist's Manual of Phenomena and Practice: With Directions for Applying Mesmerism to the Cure of Diseases, and the Methods of Producing Mesmeric Phenomena, London: H. Baillière.

- Beaunis, Henri-Étienne (1884), Recherches expérimentales sur les conditions de l'activité cérébrale et sur la physiologie des nerfs ('Experimental research on the conditions of brain activity and on the physiology of nerves'), Paris: J.-B. Baillière et Fils.

- Beaunis, Henri-Étienne (1886), Le somnambulisme provoqué: études physiologiques et psychologiques ('Induced Somnambulism: Physiological and Psychological studies'), Paris: J.-B. Baillière et fils.

- Beaunis, Henri-Étienne (1909), "Inauguration du monument du professeur Liégeois, à Bains-les-Bains: Discours de M. le Dr. Beaunis" (Inauguration of the Monument to Professor Liégeois at Bains-les-Bains: Speech by Dr. Beaunis'), Revue de l'Hypnotisme et de la Psychologie Physiologique, Vol.24, No.3, (September 1909), pp. 69-70.

- Bell, Clark (1898), "Hypnotism in the Criminal Courts", pp 183-194 in Bulletin of the Medico-Legal Congress, held at the Federal Building in the city of New York, September 4th, 5th, and 6th, 1895, New York: The Medico-Legal Journal.

- Bérillion, Edgar (ed.) (1889), Premier Congrès International de l’Hypnotisme Expérimental et Thérapeutique: Tenu à l'Hôtel-Dieu de Paris, du 8 au 12 Août 1889 ('First International Congress of Experimental and Therapeutic Hypnotism: Held at the Hôtel-Dieu in Paris, from August 8 to 12, 1889'), Paris: Edgar Doin.

- Bérillion, Edgar (1909), "Inauguration du monument du professeur Liégeois, à Bains-les-Bains: Discours de M. le Dr. Bérillion" (Inauguration of the Monument to Professor Liégeois at Bains-les-Bains: Speech by Dr. Bérillion'), Revue de l'Hypnotisme et de la Psychologie Physiologique, Vol.24, No.4, (October 1909), pp. 97-99.

- Bérillion, Edgar (1910), "Réception du buste du Inauguration du professeur Liégeois, de Nancy" (Reception at the Inauguration of the Bust of Professor Liégeois of Nancy'), Revue de l'Hypnotisme et de la Psychologie Physiologique, Vol.24, No.8, (February 1910), pp. 228-230. (Bérillion's address to the Tenth Opening Ceremony of L'Ecole de psychologie in Paris on 10 January 1910.)

- Bernheim, Hippolyte (1888), De la Suggestion et de son Application à la Thérapeutique, Deuxième édition, ('On Suggestion and its Application to Therapeutics, Second Edition'), Paris: Octave Doin.

- Bernheim, Hippolyte (Herter, C.A. trans.) (1889), Suggestive Therapeutics: A Treatise on the Nature and Uses of Hypnotism (De la Suggestion et de son Application à la Thérapeutique, Deuxième édition, 1888), New York, NY: G.P. Putnam's Sons.

- Bernheim, Hippolyte (1891), "Hypnotisme et Suggestion: doctrine de la Salpêtrière et doctrine de Nancy" ('Hypnotism and Suggestion: Doctrine of the Salpêtrière and doctrine of Nancy'), Le Temps (Supplement), (29 January 1891), pp. 1-2.

- Bernheim, Hippolyte (1897), L'hypnotisme et la suggestion dans leurs rapports avec la médecine légale ('Hypnotism and Suggestion in their Relation to Forensic Medicine'), Nancy: A. Crépin-Leblond.

- Binet, Alfred & Féré, Charles (1888), Animal Magnetism, New York: D. Appleton and Company.

- "Biographies Meusiennes: Le professeur Liégeois" ('Meuse Biographies: Professor Liégeois'), Bulletin Mensuel de la Société des lettres, sciences et arts de Bar-le-Duc, (1912), pp. CIII-CVI.

- Björnström, Fredrik (1887), Hypnotism: Its History and Present Development, New York : Humboldt Publishing Co.

- Bogousslavsky, Julien (2020), "The Mysteries of Hysteria: A Historical Perspective", International Review of Psychiatry, Vol.32, No.5-6, (August 2020), pp. 437-450. doi:10.1080/09540261.2020.1772731

- Bogousslavsky, Julien & Walusinski, Olivier (2010), "Gilles de la Tourette's criminal women: The many faces of fin de siècle hypnotism", Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery, Vol.112, No.7, (September 2010), pp. 549–551. doi:10.1016/j.clineuro.2010.03.008 PMID 20413214

- Bogousslavsky, Julien, Walusinski, Olivier & Veyrunes, Denis (2009), "Crime, Hysteria and Belle Époque Hypnotism: The Path Traced by Jean-Martin Charcot and Georges Gilles de la Tourette", European Neurology, Vol62, No.4e, (September 2009), pp. 193–199.

- Boirac, Émile (de Kerlor, Wilhem, trans.) (1918), The Psychology of the Future ("L'avenir des sciences psychiques"), London, Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co.

- Bonjean, Albert (1909a), "Inauguration du monument du professeur Liégeois, à Bains-les-Bains: Discours de M. Albert Bonjean" (Inauguration of the Monument to Professor Liégeois at Bains-les-Bains: Speech by Mons. Albert Bonjean'), Revue de l'Hypnotisme et de la Psychologie Physiologique, Vol.24, No.4, (October 1909), pp. 99-102.

- Bonjean, Albert (1909b), L'hypnotisme: ses rapports avec le droit, et la thérapeutique, la suggestion mentale ('"Hypnotism: Its Relationship with Law, and Therapy, Mental Suggestion'), Paris: Germer Baillière & Co.

- Bourneville, Désiré-Magloire, and Regnard, Paul-Marie-Léon (1880), Iconographie photographique de la Salpêtrière (service de M. Charcot) (Volume III): 1879-1880, Paris: Bureaux de Progrès Médical.

- Bramwell, John Milne (1903), Hypnotism: Its History, Practice and Theory, Grant Richards, (London), 1903.

- Brodie-Innes, John William (1891), "Legal Aspects of Hypnotism", Vol.3, No.1, (January 1891), pp. 51-62.

- Buckland, Thomas (1851), The Hand-Book of Mesmerism, etc. (Third Edition), London: Baillière.

- Carrer, Laurent (2002), Ambroise-Auguste Liébeault: The Hypnological Legacy of a Secular Saint, College Station, Texas: Virtualbookwork.com. ISBN 1-5893-9259-0

- Charcot, Jean-Martin (1890a), "Magnetism and Hypnotism", The Forum, Vol.8, No.5, (January 1890), pp. 566-577.

- Charcot, Jean-Martin (1890b), "Hypnotism and Crime", The Forum, Vol.9, No.2, (April 1890), pp. 159-168.

- Coates, James (1890), How to Mesmerise: A Manual of Instruction in the History, Mysteries, Modes of Procedure, and Arts of Mesmerism, etc., London : W. Foulsham.

- Davey, William (1862), The Illustrated Practical Mesmerist: Curative and Scientific (Sixth Edition), London: James Burns.

- de Foville, Alfred (1908), "Paroles de M. de Foville à l’occasion du décès de M. Liégeois (Séance du 22 août 1908)" ('Words from M. de Foville on the occasion of the death of M. Liégeois (Meeting of 22 August 1908)'), Séances et travaux de l'Académie des sciences morales et politiques, Vol.70, No.170 (December 1908), pp. 522-523.

- Delbœuf, Joseph (1887), "Origine des effets curatifs de l'hypnotisme" ('Origin of the curative effects of hypnotism'), Académie Royale des Sciences, des Lettres et des Beaux-arts de Belgique, Vol.57, No.6, (June 1887), pp 773-812.

- Delbœuf, Joseph (1889), "M. Liégeois et les Suggestions Criminelles" ('M. Liégeois and Criminal Suggestions'), pp.77-115 in, Joseph Delbœuf, Le Magnétisme Animal: à propos d’une visite à l’École de Nancy ('Animal Magnetism: About a visit to the Nancy School'), Paris: Germer Baillière.

- Delbœuf, Joseph (1891), "L'opinion de M. le professeur Delbœuf", ('The Opinion of Professor Delbœuf (on the Case of Gabriell Bompard)')", Revue de l'Hypnotisme et de la Psychologie Physiologique, Vol.5, No.7, (January 1891), pp. 216-218.

- Delbœuf, Joseph (1891), "Comme quoi il n'y a pas d'hypnotisme" ('So it turns out there is no hypnotism'), Revue de l'Hypnotisme et de la Psychologie Physiologique, Vol.6, No.5, (November 1891), pp. 129-135.

- Delbœuf, Joseph (1892), "On Criminal Suggestion", The Monist, Vol.2, No.3, (April 1892), pp. 363-385.

- Diamond, Bernard L. (1980), "Inherent Problems in the Use of Pretrial Hypnosis on a Prospective Witness", California Law Review, Vol.68, No.2, (March 1980), pp.313-349. JSTOR 3479989

- Durand (de Gros), Joseph-Pierre (1895), "Suggestions Hypnotiques Criminelles: Lettre au docteur Liébeault" ('Criminal Hypnotic Suggestions: Letter to Dr. Liébeault'), Revue de l'Hypnotisme et de la Psychologie Physiologique, Vol.10, No.1, (July 1895), pp. 8-23.

- Esdaile, James (1846), Mesmerism in India, and its Practical Application in Surgery and Medicine, London: Longman, Brown, Green & Longmans.

- Finn, Michael R. (2017), Figures of the Pre-Freudian Unconscious from Flaubert to Proust, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9-781-3168-8215-3

- Floquet, Gaston (1909), "Inauguration du monument du professeur Liégeois, à Bains-les-Bains: Discours de M. le professeur Floquet" (Inauguration of the Monument to Professor Liégeois at Bains-les-Bains: Speech by Professor Floquet'), Revue de l'Hypnotisme et de la Psychologie Physiologique, Vol.24, No.3, (September 1909), pp. 65-67.

- Forel, August (1907), Hypnotism; or, Suggestion and Psychotherapy: A Study of the Psychological, Psycho-physiological and Therapeutic Aspects of Hypnotism, New York: Rebman Company.

- Gauld, Alan (1992), A History of Hypnotism, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-30675-1

- Gilles de la Tourette, Georges (1887), L'hypnotisme et les états analogues au point de vue médico-légal: les états hypnotiques et les états analogues, les suggestions criminelles, cabinets de somnambules et sociétés de magnétisme et de spiritisme, l'hypnotisme devant la loi ('Hypnotism and similar states from a forensic point of view: hypnotic states and similar states, criminal suggestions, somnambulists' practices and societies of magnetism and spiritism, hypnotism before the law'), Paris: E. Plon, Nourrit & Co.

- Gilles de la Tourette, Georges (1891a), "Correspondance: L’Epilogue d’un procès célèbre" ('The epilogue of a famous trial (Letter to the editor)'), Le Progrès Médical, Vol.13, No.7, (14 February 1891), pp. 135-136.

- Gilles de la Tourette, Georges (1891b), L'épilogue d'un procès célèbre (Affaire Eyraud-Bompard) ('The epilogue of a famous trial (Eyraud-Bompard Affair)'), Paris: Aux Bureaux du Progrès Médical.

- Goetz, Christopher G. (2004), "Medical-legal issues in Charcot’s neurologic career", Neurology, Vol.62, No.10, (May 2004), pp. 1827–1833. doi:10.1212/01.WNL.0000125300.26623.FC

- Gordon, E., Kraiuhin, C., Kelly, P. & Meares, R. (1984), "The Development of Hysteria as a Psychiatric Concept", Comprehensive Psychiatry, Vol.25, No.5, (September–October 1984), pp. 532-537. doi:10.1016/0010-440X(84)90053-1

- Grasset, Joseph (1910) (Tubeuf, René Jacques, trans.), The Marvels Beyond Science (L'occultisme hier et aujourd'hui; le merveilleux préscientifique) Being a Record of Progress made in the Reduction of Occult Phenomena to a Scientific Basis, New York: Funk & Wagnalls Company.

- Gravitz, Melvin A. (1991), "Early Theories of Hypnosis: A Clinical Perspective", pp. 19-42 in S.J. Lynn and J.W. Rhue (ed.), Theories of Hypnosis: Current Models and Perspectives, New York, NY: Guildford Press. ISBN 978-0-8986-2343-7

- Guilhermet, Georges (1909), "Eloge du professeur Liégeois (de Nancy)", ('Eulogy for Professeur Liégeois of Nancy', read to the 17 June 1909 meeting of the Société d'hypnologie et de psychologie), Revue de l'Hypnotisme et de la Psychologie Physiologique, Vol.24, No.1, (July 1909), pp. 18-23.

- Hardy, Spencer (1950), "The Hypnotised Beauty", The (Sydney) World's News, (Saturday, 4 November, pp. 1, 6, 7.

- Harris, Ruth (1985), "Murder under hypnosis", Psychological Medicine, Vol.15, No.3, (August 1985), pp. 477-505. doi:10.1017/S0033291700031366

- "Homage" (1909), "Hommage posthume à Jules Liégeois (de Nancy)" ('Posthumous Tribute to Jules Liégeois (of Nancy)'), L'Informateur des Aliénistes et des Neurologistes (Supplément mensuel de l'Encéphale), Vol.4, No.10, (25 October 1909), pp. 280-282.