John Currour

John Currour was a goldsmith in Edinburgh who worked for James IV of Scotland and Margaret Tudor.[1]

An Act of Parliament of 1493 mentions that John Currour had coined some money, and the coins would be honoured.[2] Currour paid a fee of composition to the crown in 1494 to acquire a hoard of silver found in Banff.[3]

In 1503, Currour made a crown for Margaret Tudor, and Matthew Auchinleck repaired the king's crown and made buttons for their costumes. Margaret's crown was made from 83 gold coins.[4] An English herald described the crown as a "varey rich croune of gold garnished with pierrery and perlez".[5]

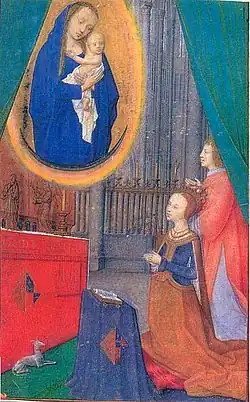

In the days after the wedding, Currour provided rings, a heart of gold, an image of the Virgin Mary, and a gold cross for Margaret Tudor. Currour also made a unicorn jewel for James IV with a pendant pearl.[6]

In January 1504, Currour provided New Year's Day gifts, mended two collars with swans, supplied pearls for gold crosses which James IV gave to Margaret, and set a stone for the English "Lady Mistress" of the queen's household. This was either "Mistress Musgrave" or Joan, Lady Guildford. James IV had given a gold chain to Lady Guildford in October,[7] and Margaret had written "Cest marguerite" in Lady Guildford's prayer book.[8] Among the New Year's Day gifts in 1507, Currour provided a gold chain given to another English courtier Eleanor Verney.[9]

Currour gilded armour for James IV in November 1511. Thomas and William Currour were also working for the king at this time. William Currour was involved in organising the pageant of the Passion in Edinburgh in 1507.[10] He made a gold heart jewel and a silver powder horn, and his wife provided a gold "chaffron" for Margaret Tudor to wear as a headdress with a "target" brooch or badge. The account specifies that both "chaffron" and "target" were for the queen's hood.[11]

Currour took ownership of a house on the Cowgate by sasine in November 1509. The Confraternity of the Holy Blood commissioned him to make a eucharistic vessel for their altar in St Giles' Cathedral in October 1512. It was to be made of silver of the fineness of an English groat.[12]

References

- ^ R. L. Mackie, King James IV of Scotland: A Brief Survey of His Life and Time, p. 103.

- ^ The Records of the Parliaments of Scotland to 1707, K.M. Brown et al eds (St Andrews, 2007-2025), A1493/5/11 Date accessed: 4 August 2025.

- ^ Thomas Dickson, Accounts of the Treasurer, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1877), p. 213.

- ^ Ian Simpson Ross, William Dunbar (Brill, 1981), p. 57: Papers Relative to the Regalia of Scotland (Edinburgh: Bannatyne Club, 1829), p. 29.

- ^ Thomas Hearne, De rebus Britannicis collectanea, 4 (London, 1774), pp. 292–293.

- ^ Lucinda H. S. Dean, Death and the Royal Succession in Scotland: Ritual, Ceremony and Power (Boydell & Brewer, 2024), p. 267: James Balfour Paul, Accounts of the Treasurer of Scotland, 1500-1504, vol. 2 (Edinburgh, 1900), pp. lxiii, 206, 217.

- ^ Accounts of the Treasurer of Scotland, 1500-1504, vol. 2 (Edinburgh, 1900), pp. 401, 412-413.

- ^ Susan Brigden, "Reading and rhyming in the Black Friars", Liber amicorum H. R. Woudhuysen: A Bibliographical Tribute (Oxford, 2024), p. 53.

- ^ Accounts of the Treasurer of Scotland, 1500-1504, vol. 3 (Edinburgh, 1901), p. 360.

- ^ David Robertson and Marguerite Wood, Castle and Town (Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd, 1928), pp. 208–209.

- ^ Accounts of the Treasurer of Scotland, 1507-1513, vol. 4 (Edinburgh, 1902), pp. 113, 196, 213.

- ^ Protocol Book of John Foular (Scottish Record Society, 1940), p. 110 no. 595, 160 no. 848.