King Wu of Zhou

| King Wu of Zhou 周武王 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

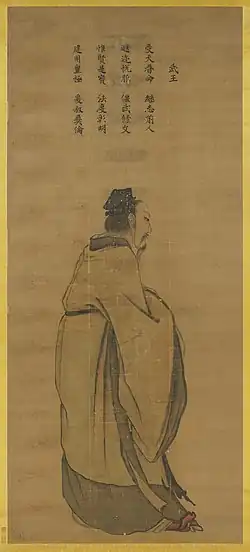

Depiction of King Wu by Ma Lin | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Elder of the Predynastic Zhou | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 1050–1046 BCE | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | King Wen of Zhou | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| King of the Zhou dynasty | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 1046–1043 BCE | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | King Zhou of Shang (Shang dynasty) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | King Cheng of Zhou | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | Ji Fa (姬發) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 1043 BCE Haojing, Western Zhou | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse | Yi Jiang | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Issue | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| House | Ji | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dynasty | Zhou | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Father | King Wen of Zhou | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mother | Tai Si | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 周武王 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Martial King of Zhou | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 姬發 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 姬发 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

King Wu of Zhou (died c. 1043 BC), personal name Ji Fa, was the founding king of the Chinese Zhou dynasty. The chronology of his reign is disputed but is generally thought to have begun around 1046 BC and ended with his death three years later.[1]

King Wu was the second son of the Zhou elder Ji Chang (posthumously titled King Wen) and Tai Si. In most accounts, his older brother Bo Yikao was said to have predeceased his father, typically at the hands of King Zhou of Shang, the last king of the Shang dynasty. In the Book of Rites, however, it is assumed that his inheritance represented an older tradition among the Zhou of passing over the eldest son.[2] (Fa's grandfather Jili had likewise inherited Zhou despite having two older brothers.)

Upon his succession, Fa worked with his father-in-law Jiang Ziya to accomplish an unfinished task: overthrowing the Shang dynasty. During the ninth year of his reign, Fa marched down the Yellow River to the Mengjin ford and met with more than 800 elders.[3] He constructed an ancestral tablet with his father's posthumous name as King Wen and placed it on a chariot in the middle of the host; considering the timing unpropitious, though, he did not yet attack Shang. Around 1046 BC by current estimates, King Wu took advantage of Shang disunity to launch an attack along with many neighboring elders. The Battle of Muye destroyed Shang's forces and King Zhou set his palace on fire, dying within.

King Wu followed his victory by moving his court from Feng to nearby Hao, leaving the older settlement to serve as a site for ancestral temples and gardens. He granted many 'feudal' states to his 16 younger brothers and to clans allied by marriage, but his death soon after ascension provoked several rebellions against his young heir King Cheng and the regent Ji Dan, even from three of his brothers.

A burial mound at Zhouling in Xianyang Prefecture, Shaanxi, was once thought to be King Wu's tomb. It was fitted with a headstone bearing Wu's name under the Qing dynasty. Modern archeology has since concluded that the tomb is not old enough to be from the Zhou dynasty and is more likely to be that of a Han dynasty royal. The true location of King Wu's tomb remains unknown but it is likely to be in the area of modern Xianyang and Xi'an.

King Wu is considered one of the great heroes of China, together with the mythical Yellow Emperor and the legendary Yu the Great.

Family

Queens:

- Yi Jiang, of the Lü lineage of the Jiang clan of Qi (邑姜 姜姓 呂氏), the first daughter of the Great Duke of Qi; the mother of Song and Yu

Sons:

- Prince Song (王子誦; 1060–1020 BC), ruled as King Cheng of Zhou from 1042 to 1021 BC

- Second son, ruled as the Monarch of Yu (邘), the ancestor of the surname Yu (于)

- Third son, Prince Yu (王子虞), ruled as the Marquis of Tang from 1042 BC

- A son who ruled as the Marquis of Ying (應)

- A son who ruled as the Marquis of Han

Daughters:

- First daughter, Da Ji (大姬)

- Married Duke Hu of Chen (1071–986 BC)

- Youngest daughter, personal name Lan (蘭)

- Married Duke Yǐ of Qi (d. 933 BC)

See also

References

- ^ These dates are those of the People's Republic of China's official Xia–Shang–Zhou Chronology Project, although they remain controversial.

- ^ Book of Rites, Tan Gong I, 1. Accessed 4 Nov 2012.

- ^ Sima, Yi. Records of the Grand Historian.