Jelonki, Warsaw

Jelonki | |

|---|---|

Apartment buildings at Doroszewskiego Street. | |

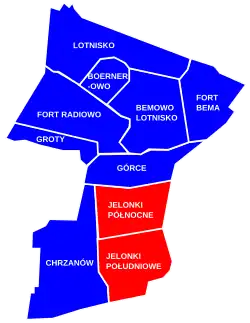

Location of Jelonki within the district of Bemowo, in accordance to the City Information System, which divides the neighbourhood into two areas, Jelonki Północne and Jelonki Południowe. | |

| Coordinates: 52°13′42″N 20°54′35″E / 52.22833°N 20.90972°E | |

| Country | |

| Voivodeship | Masovian |

| City county | Warsaw |

| District | Bemowo |

| City Information System areas | Jelonki Północne Jelonki Południowe |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Area code | +48 22 |

Jelonki is a neighbourhood in the Bemowo district of Warsaw, Poland. It is a mixed residential area with low-rise single-family neighbourhoods of Stare Jelonki, Nowy Chrzanów, and Friendship Estate, and mid- and high-rise multifamily housing estates of Górczewska, Jelonki, and Lazurowa. It includes the Górczewska Park, and features two stations of the Warsaw Metro, Bemowo and Lazurowa, as well as two railway stations, Warszawa Jelonki, and Warszawa Głowna Towarowa. The area is divided into two City Information System areas, Jelonki Północne (North Jelonki) and Jelonki Południowe (South Jelonki).

Jelonki was founded in the 19th century as a small farming community. In the 1920s, its land was partitioned, and the village was developed as a garden suburb. It was incorporated into Warsaw in 1951. In 1952, the Frienship Estate, a neighbourhood of wooden houses was built within its current boundaries, originally providing accommodation for Soviet migrant labourers, and after 1955, for university students and teachers. In the 1970s and 1980s, three large housing estates with mid- and high-rise apartment buildings were constructed, including Górczewska, Jelonki, and Lazurowa.

Toponomy

The name Jelonki is a Polish plural diminutive form of the term meaning cervus, a genus of deer which was present in the area. Historically, before 1951, the neighbourhood was also known as Jelonek, a singular diminutive form.[1]

History

Founding and development

A small farming community, later known as Jelonki, was established in the area in the 19th century, next to the village of Odolany, to the north of the Poznań Road (now Połczyńska Street).[2][3][1] The village was bought by Bogumił Schneider, a businessman, who moved to the area from Westphalia. In the second half of the century, he built his residence in the form of a brick manor house, near the current Fortuny Street. In 1902, he also built a second residence, a wooden villa at the current 59 Połczyńska Street, which stands to this day. In 1904, the village had 729 inhabitants and included 19 houses and a school.[2][1] After the purchase, the village began being known as Jelonki and Jelonek.[2][1]

In 1846, the Bogumił Schneider Brickworks and Roof Tiles Factory (Polish: Zakłady Cegielniane i Fabryka Dachówek „Bogumił Schneider”), in the area, which produced bricks, roof tiles, and ceramics.[2][1][4][5] The factory had a good reputation, being locally known for the good quality of its products. Many houses and tenements in Warsaw were built from its bricks.[2][1][6][5] It was also commissioned by the Imperial Russian Army, to provide materials for the construction of Forts II, III, and IV of the Warsaw Fortress, a series of fortifications built around the city between 1883 and 1890.[5][7] It extracted the clay for its products locally, leaving behind pits, some of which were later flooded, forming small ponds, including Jelonek and Schneider Clay Pits, which are present within the neighbourhood boundaries to the present day.[5][8][9] The factory operated until 1940, when, while under German occupation, it was ordered to be closed down.[1][5]

Around 1877, fifteen German settlers founded a hamlet of Nowy Chrzanów, located along the current Okrętowa Street.[2]

In 1927, inspired by the garden city movement, the Schneider family divided and sold a portion of their land, promoting the construction of villas and gardens in the village. They also founded a garden and a fruit tree orchard, located around their summer residence, and also drew plans of wide town streets, including Schneider Avenue, which currently forms Powstańców Śląskich Street. In 1932, the settlement had been renamed to Miasto-Ogród Jelonek (Garden Town of Jelonek).[2][1] A marketplace, known as the John III Sobieski Square, now known as the Castellan Square, was also built there.[10]

Second World War

Jelonki and Nowy Chrzanów were captured by German forces in early September 1939 during the siege of Warsaw in the Second World War. On 18 September 1939, they were recaptured in a counter-offensive by the 360th Infantry Regiment of the Polish Armed Forces, commanded by lieutenant colonel Leopold Okulicki. Their forces included four infantry companies, with heavy machine gun platoons, and one mortar platoon.[11][12] They were also supported by a artillery batteries, a platoon of 7TP light tanks, as well as a company of the Capital Battalion, with the latter being pushed back during the attacks.[12][13][14] The motorized platoon suffered heavy loses in an encounter against German Panzer 35(t) light tanks.[13] The villages were captured with severe losses suffered by the Polish infantry, and remained under Polish control until the capitulation of Warsaw on 28 September 1939.[11][12]

In 1943, Jelonki had 3,826 inhabitants.[15]

Expansion as a suburb

Since 1867, the area was part of the municipality of Blizne.[2] On 25 March 1938, a village assembly (Polish: gromada) of Jelonki, with the seat in Miasto Ogród Jelonek, was founded as a subdivision of the municipality.[16] After the war, the village also became the seat of the municipal government. In 1947, the village was connected with Warsaw, via the bus route W, between the Wola tram depot and the Castellan Square.[1]

In 1943, the Schneiders family donated 28 hectares of their land to the municipality, for the symbolic price of 1 złoty, for the development of streets, churches, schools, preschools, a town hall, and other objects. The land was donated for the symbolic price of 1 złoty. After the war, Miasto Ogród Jelonek became the seat of the municipal government. In 1947, the village was connected with Warsaw, via the bus route W, between the Wola tram depot at Młynarska Street and the Castellan Square.[1] On 14 May 1951, the area was incorporated into the city of Warsaw, becoming part of the Wola district.[17][18] On 29 December 1989, following an administrative reform in the city, it became part of the municipality of Warsaw-Wola, and on 25 March 1994, of the municipality of Warsaw-Bemowo, which, on 27 October 2002, was restructured into the city district of Bemowo.[18] In 1997, it was subdivided into ten areas of the two City Information System areas, with the neighbourhood being divided into Jelonki Południowe (South Jelonki) and Jelonki Północne (North Jelonki).[19]

In 1949, the Warszawa Główna Towarowa railway station for cargo trains was opened at to the south of Jelonki and Połczyńska Streets.[20] In 1952, the Warszawa Jelonki railway station was established near the corner of Strąkowska and Wincentego Pola Streets.[21]

In 1952, the Friendship Estate, was developed to the north of Jelonki. It provided housing for several thousand labourers from the Soviet Union, employed at the construction of the Palace of Culture and Science.[22][23] The government acquired the land from the owners via the compulsory purchase. Two types of wooden buildings were built in the neighbourhood; pavilions with suites for labourers and single-family detached houses for technicians.[23] They were shipped in prefabricated pieces to the city, and assembled on site.[24] According to some sources, a portion of the buildings were shipped from the prisoner-of-war camp Stalag I-B near Olsztynek, Poland.[25][26] The neighbourhood also included a cinema, a student club, a bathhouse, a medical clinic, a boiler room, and two pitches.[23][27] In 1952, it was connected to a sewage network, with the construction of the nearby pumping station.[28] At its peak, the neighbourhood had 4,500 inhabitants. Numerous festivals, Polish and Soviet youth meetings, and sports competitions were hosted there.[23] After the end of the construction of the Palace of Culture and Science in 1955, the neighbourhood was given by the city to the Ministry of Higher Education, which designated it for student housing for the universities in the city.[29][22] In September 1955, it was inhabited by 3,000 students, as well as teaching assistants.[22] It was connected with the rest of the city via two bus lines.[30] The student festival Jelonkalia has also begun being hosted annually.[31]

In 1958, association football club Robotniczy Klub Sportowy Świt merged with club Ludowy Klub Sportowy Lech Jelonki, which played on the pitch at Połczyńska Street. In 1960, the club again merged with Dąb Jelonki, taking over its pitch at 12 Oświatowa Street. In the following years, it was acquired by the Warsaw Gasworks, with most of the players being its employees, and renamed to Gazowniczy Klub Sportowy Świt Warszawa. Later, it became a property of PGNiG.[32][33]

In 1968, the Church of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross, belonging to the Catholic denomination, was built in Jelonki at 31 Brygadzistów Street.[34][35]

In 1974, the Wola Heating Plant was opened at 21 Połczyńska Street, as part of the city's heat network.[36]

.jpg)

Between 1974 and 1981, the housing estates of Górczewska, Jelonki, and Lazurowa, were developed to the north and around the historical low-rise houses of Jelonki. They consisted and high-rise apartment buildings, constructed in the large panel system technique. Additionally, the Górczewska Park, was developed in 1980 around the buildings of the neighbourhood of Górczewska.[2][22] In 2008 there was opened an amphitheatre.[37]

Since 1987, the Schneider Villa at 59 Połczyńska Street, houses the Warsaw Wola Pentecostal Church.[38]

In 1992, a tram line tracks were constructed alongside Górczewska, Powstańców Śląskich, and Połczyńska Streets.[39] In 1995, the Church of Mary the Mother of God, belonging to the Catholic denomination, was built was at 13 Muszlowa Street.[40]

In 2000, the Bemowo Civic Centre, which houses the district government, was opened at 70 Powstańców Śląskich Street.[41][42]

In 2006, the Bemowo Cultural Centre was opened at 18 Rozłogi Street.[43]

In 2022, the Bemowo station of the M2 line of the Warsaw Metro rapid transit underground system, was opened at the intersection of Górczewska and Powstańców Śląskich Streets.[44] Since 2022, the Lazurowa station is also being constructed in the neighbourhood, at the intersection of Górczewska and Lazurowa Streets. It is planed to be opened in 2026.[45][46]

Overview

Housing

Jelonki is a residential area with mixed low-rise single-family and mid- and high-rise multifamily housing. To the south of Czułchowska, it includes the neighbourhoods of Stare Jelonki and Nowy Chrzanów with detached and semi-detached houses.[2][1][47] They are bordered by housing estates of Lazurowa to the west of Drzeworytników Street, and Jelonki to the east of Drzeworytników and Brygadzistów Streets, as well as Górczewska to the north of Czułchowska Street, and to the east of Powstańców Śląskich Street. They are composed of mid- and high-rise apartment buildings, mostly dating to the 1970s.[2][22] To the northeast, the area also has a detached continuation of Stare Jelonki, placed between Olbrachta, Czułchowska Streets, Znana, and Powstańców Śląskich Streets, partially extending into the Wola district.[2][1][47] Additionally, the area also includes the Friendship Estate located in the northeast, between Górczewska, Olbrachta, and Powstańców Śląskich Streets. It consists of historic wooden houses, dating to 1952, which are used as student dormitories.[23][29] It also has the Bemowo Civic Centre at 70 Powstańców Śląskich Street.[48] Among other historic and notable buildings, Jelonki also includes the Schneider Villa, a wooden villa at 9 Połczyńska Street, dating to 1902, which used to be the residence of the Schneider family, which owned the settlement in the 19th and early 20th centuries.[1]

Parks and nature

.jpg)

The Górczewska Park, with an area of 20.47 ha, is the largest open green space in the neighbourhood. It is located in the centre of the housing esatate of Górczewska, between Górczewska, Powstańców Śląskich, Czułchowska, and Lazurowa Streets.[22][37] Jelonki also includes the Castellan Square, a small garden square, at the corner of Powstańców Śląskich and Strąkowska Streets.[10]

The neighbourhood also have three man-made ponds, known as Jelonek and Schneider Clay Pits. They were formed in the 20th century, from flooded clay pits.[9]

Culture and sports

The neighbourhood includes the Bemowo Cultural Centre at 18 Rozłogi Street, and an amphitheatre in Górczewska Park.[43][37] Additionally, the Friendship Estate, hosts annually the student festival Jelonkalia.[31][49] Jelonki also includes the homefield of the association football club Gazowniczy Klub Sportowy Świt Warszawa, placed at 12 Oświatowa Street, which has a capacity of 140 viewers.[50]

Transit and infrastructure

The area includes the Bemowo station of the M2 line of the Warsaw Metro rapid transit underground system, at the intersection of Górczewska and Powstańców Śląskich Street.[44] Currently, at the intersection of Górczewska and Lazurowa Street, the Lazurowa station is also being built, with plans to open in 2026.[45][46] It also has two railway stations, the Warszawa Główna Towarowa for cargo trains near Połczyńska Street, and Warszawa Jelonki for passenger trains, near the corner of Strąkowska and Wincentego Pola Streets.[20][21] The neighbourhood also includes the tracks of the tram line network, alongside Górczewska, Powstańców Śląskich and Połczyńska Streets.[39]

Jelonki also includes the Wola Heating Plant at 21 Połczyńska Street, which forms part of the city's heat network.[36]

Religion

Jelonki has two Catholic churches, the Church of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross at 31 Brygadzistów Street, and the Church of Mary the Mother of God, at 13 Muszlowa Street.[40][35][40] Additionally, it also incluces the Warsaw Wola Pentecostal Church, housed in the historic Schneider Villa, at 59 Połczyńska Street.[38]

Boundaries

Jelonki is divided into two City Information System areas, Jelonki Północne to the north, and Jelonki Południowe to the south. Their border is marked by Czułchowska Street. When combined, their boundaries are approximately determined by Górczewska Street to the north; railway line no. 509, and Dzwigowa Street to the east; around the Warszawa Główna Towarowa railway station to the south; and Szegligowska Street, and Lazurowa Street to the west.[19]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Życie przed wielką płytą, czyli skąd się wzięły Jelonki". tustolica.pl (in Polish). 25 November 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Barbara Petrozolin-Skowrońska (editor): Encyklopedia Warszawy. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, 1994, ISBN 83-01-08836-2. (in Polish)

- ^ Jelonki (1); In: Geographical Dictionary of the Kingdom of Poland, vol. 3: Haag – Kępy, Warsaw, 1882, p. 561. (In Polish)

- ^ Zakłady Cegielniane i Fabryka Dachówek "Bogumił Schneider". In: Przegląd Techniczny, 3 October 1903. (In Polish)

- ^ a b c d e Przemysław Burkiewicz: Cegły z Jelonek zbudowały Warszawę. In: Bemowo News, July 2011, p. 21. ISSN 1897-9777. (In Polish)

- ^ Zakłady Cegielniane i Fabryka Dachówek "Bogumił Schneider". In: Przegląd Techniczny, 3 October 1903. (In Polish)

- ^ Lech Królikowski: Twierdza Warszawa. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Bellona, 2002. ISBN 83-11-09356-3. (In Polish)

- ^ Barbara Petrozolin-Skowrońska (editor): Encyklopedia Warszawy. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, 1994, p. 212, ISBN 83-01-08836-2. (in Polish)

- ^ a b Łukasz Szkudlarek: Analiza powierzchniowa zlewni. Charakterystyka i ocena funkcjonowania układu hydrograficznego, ze szczególnym uwzględnieniem systemów melioracyjnych na obszarze m.st. Warszawy wraz z zaleceniami do Studium uwarunkowań i kierunków zagospodarowania przestrzennego m.st. Warszawy i planów miejscowych. Warsaw: Warsaw, 2015, p. 14. (in Polish)

- ^ a b "Wiosna zawitała na dawny rynek Jelonek". tustolica.pl (in Polish). 16 April 2015.

- ^ a b Wacław Stanisław Godzemba-Wysocki, Marian Domagała-Zamorski: Historia Kaniowszczyków, czyli dzieje 30 Pułku Piechoty Strzelców Kaniowskich. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo M. M., 2006, pp. 124–125. ISBN 83-89710-28-5. (in Polish)

- ^ a b c Ludwik Głowacki: Obrona Warszawy i Modlina na tle kampanii wrześniowej 1939. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Ministerstwa Obrony Narodowej wydanie V, 1985, pp. 236–237. ISBN 83-11-07109-8. (in Polish)

- ^ a b Dariusz Kaliński: Twierdza Warszawa. Pierwsza wielka bitwa miejska II wojny światowej. Kraków: Znak Horyzont, 2022, pp. 394–395. ISBN 978-83-240-8785-3. (in Polish)

- ^ Artur Szczepaniak: Batalion Stołeczny 1936–1939. Wielka Księga Piechoty Polskiej 1918–1939. T. 32. Warsaw: Edipresse Polska S.A., 2018, pp. 71–72. ISBN 978-83-7945-413-6. (in Polish)

- ^ Gemeinde- und Dorfverzeichnis für das Generalgouvernement Archived 2021-01-14 at the Wayback Machine. 1943.

- ^ "Warszawski Dziennik Wojewódzki : dla obszaru Województwa Warszawskiego. 1938, nr 4". jbc.bj.uj.edu.pl (in Polish).

- ^ "Rozporządzenie Rady Ministrów z dnia 5 maja 1951 r. w sprawie zmiany granic miasta stołecznego Warszawy". isap.sejm.gov.pl (in Polish).

- ^ a b Andrzej Gawryszewski: Ludność Warszawy w XX wieku. Warsaw: Instytut Geografii i Przestrzennego Zagospodarowania PAN, 2009, pp. 44–50. ISBN 978-83-61590-96-5. (in Polish)

- ^ a b "Dzielnica Bemowo". zdm.waw.pl (in Polish).

- ^ a b "Warszawa Główna Towarowa". atlaskolejowy.net (in Polish).

- ^ a b "Warszawa Jelonki". atlaskolejowy.net (in Polish).

- ^ a b c d e f Lech Chmielewski: Przewodnik warszawski. Gawęda o nowej Warszawie. Warsaw: Agencja Omnipress, Państwowe Przedsiębiorstwo Wydawnicze Rzeczpospolita, 1987. ISBN 8385028560. (in Polish)

- ^ a b c d e Jarosław Zieliński: Pałac Kultury i Nauki. Łódź: Księży Młyn, 2012, pp. 33–34. ISBN 978-83-7729-158-0. (in Polish)

- ^ Michał Krasucki: Warszawskie dziedzictwo postindustrialne. Warsaw: Fundacja Hereditas, 2011, p. 337. ISBN 978-83-931723-5-1. (in Polish)

- ^ Rafał Jabłoński: Historie warszawskie. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo TRIO, 2012, p. 218. ISBN 978-83-7436-314-3. (in Polish)

- ^ "Historia Olsztynka". olsztynek.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2018-09-16.

- ^ Jarosław Trybuś: Przewodnik po warszawskich blokowiskach. Warsaw: Museum of Warsaw Rising, p. 186. ISBN 978-83-60142-31-8. (in Polish)

- ^ Henryk Janczewski: Warszawa. Geneza i rozwój inżynierii miejskiej. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Arkady, 1971, p. 169. (in Polish)

- ^ a b Encyklopedia Warszawy. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, 1994, p. 710. ISBN 83-01-08836-2. (in Polish)

- ^ Rafał Jabłoński: Historie warszawskie. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo TRIO, 2012, p. 191. ISBN 978-83-7436-314-3. (in Polish)

- ^ a b "Kalendarz warszawski 1 IV–30 VI 1986", Kronika Warszawy, no. 69, p. 210, 1987. (in Polish)

- ^ "'Futbol dawnej Warszawy' i dzisiejszego Bemowa". tustolica.pl (in Polish). 8 May 2013.

- ^ "Koniec najstarszego klubu Bemowa? Boisko na Jelonkach sprzedane". tustolica.pl (in Polish). 22 July 2020.

- ^ Grzegorz Kalwarczyk: Przewodnik po parafiach i kościołach Archidiecezji Warszawskiej. Tom 2. Parafie warszawskie. Warsaw: Oficyna Wydawniczo-Poligraficzna Adam, 2015, p. 479. ISBN 978-83-7821-118-1. (in Polish)

- ^ a b "Warszawa. Podwyższenia Krzyża Świętego". archwwa.pl (in Polish).

- ^ a b Marian Gajewski: Urządzenia komunalne Warszawy. Zarys historyczny. Warsaw: Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, 1979, p. 175. ISBN 83-06-00089-7. (in Polish)

- ^ a b c "Michael Jackson znika z Bemowa. Władze dzielnicy zdecydowały o zmianie nazwy amfiteatru". metrowarszawa.pl (in Polish). 25 July 2019.

- ^ a b M. Kwiecień: "Zbór Warszawa Wola", Chrześcijanin, no. 11–12, 1992. (in Polish)

- ^ a b "Warszawa z nową trasą tramwajową na Powstańców Śląskich". transport-publiczny.pl (in Polish). 14 February 2015.

- ^ a b c "Warszawa. Bogurodzicy Maryi". archwwa.pl (in Polish).

- ^ Rafał Jabłoński: Historie warszawskie. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo TRIO, 2012, p. 187. ISBN 978-83-7436-314-3. (in Polish)

- ^ Przemysław Burkiewicz: "Dwie dekady samorządności", Twoje Bemowo, no. 01/2014. Warsaw: Bemowo District Office, p. 6. ISSN 1897-9777. (in Polish)

- ^ a b "Bemowskie Centrum Kultury. O nas". bemowskie.pl (in Polish). 30 October 2023.

- ^ a b "Metro jedzie na Bemowo. Dwie nowe stacje otwarte". transport-publiczny.pl (in Polish).

- ^ a b Jarosław Osowski (1 February 2023). "Budowa końcówki metra na ubogo, pytania do Trzaskowskiego bez odpowiedzi. Padł tylko jeden termin". warszawa.wyborcza.pl (in Polish).

- ^ a b Michał Mieszko Skorupka (1 February 2023). "Druga linia metra w Warszawie. Rafał Trzaskowski: Pasażerowie pojadą na Karolin w 2026 roku". warszawa.naszemiasto.pl (in Polish).

- ^ a b Studium uwarunkowań i kierunków zagospodarowania przestrzennego miasta stołecznego Warszawy ze zmianami. Warsaw: Warsaw City Council, 1 March 2018, pp. 10–14. (in Polish)

- ^ "Bemowo. Kontakt". bemowo.um.warszawa.pl (in Polish).

- ^ "Warszawskie osiedla Zatrasie i Przyjaźń będą zabytkami". dzieje.pl (in Polish). 4 November 2023.

- ^ "Gazowniczy Klub Sportowy "Świt"". bemowo.um.warszawa.pl (in Polish).