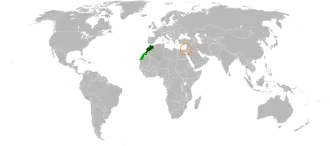

Israel–Morocco relations

| |

Morocco |

Israel |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

| Embassy of Morocco, Tel Aviv (upgrading liaison office)[1][2] | Embassy of Israel, Rabat (under construction)[3] |

The State of Israel and the Kingdom of Morocco formally established diplomatic relations in 2020,[4] when both sides signed the Israel–Morocco normalization agreement in light of the Abraham Accords.[5] While official ties had previously not existed due to the Arab–Israeli conflict, the two countries maintained a secretive bilateral relationship on a number of fronts following the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. For many years, Moroccan king Hassan II facilitated a relationship with Israeli authorities, and these ties are considered to have been instrumental in stabilizing Morocco and striking down possible anti-monarchy threats within the country.[6][7] The Israeli passport is accepted for entry into Morocco, with a visa granted on arrival.[8] With the bilateral normalization agreement in December 2020, Morocco officially recognized Israeli statehood. Almost three years later, in July 2023, Israel officially recognized Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara.[9][10][11]

History

Background

The history of Jewish communities in what is now Morocco extends approximately two millennia.[12][13]

In the early 20th century, Zionism, the movement to establish a Jewish state in Palestine, spread from Europe to Moroccan coastal cities and then spread slowly among Morocco's Jewish communities over the following decades.[14][15][16] Only after the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, however, was there notable Zionist emigration from Morocco.[14] The migration of Moroccan Jews to Israel had significant support from external Zionist organizations, including the Jewish Agency, Mossad Le'Aliyah, and the American Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS), and there were a number of initiatives to facilitate this migration, including the Caisse d’Aide aux Immigrants Marocains or Cadima (Hebrew: קדימה, 'forward'; 1949–1956),[17] Operation Yachin (Hebrew: מבצע יכין; 1961–1964),[18] and ha-Misgeret (המסגרת 'The Framework'; 1956–1964).[19] By the end of the 20th century, roughly two thirds of Moroccan Jews migrated to Israel and only a small fraction of the Moroccan Jewish community remained in Morocco.[14][18]

Period between the establishment of the State of Israel and Moroccan independence (1948–1956)

1948 Palestine War and the establishment of the State of Israel

The global Zionist movement had not been very interested in the Jews of Morocco until the establishment of the State of Israel in Palestine in 1948.[20] Only from then was there significant Zionist emigration from Morocco.[20] From 1947–1949 the Jewish Agency organized emigration, though it was illegal; prospective migrants caught attempting to cross the border into Algeria would be sent back.[20] Clandestine migration through Algeria during the Palestine war led to the 1948 anti-Jewish riots in Oujda and Jerada in June.[21]

Shay Hazkani writes that about 20,000 Moroccan Jews migrated to Israel in 1948–49, and there was a manifested desire to leave Israel and return to Morocco due to Ashkenazi racism, and that this urge was most apparent among the 645–1600 North Africans (most of whom were Moroccan) who fought in the Israeli military in the 1948 Palestine War.[22] Based on their personal letters that were intercepted by the Israeli military postal censorship bureau, 70% of them wanted to return to their country of origin and warned their families not to come to Israel.[22] Among those who weren't in the military, 60% were actively trying to return to their countries and 90% were urging their families not to come to Israel.[22]

Cadima and Seleqseya

From 1949 to 1956, Cadima, a migration apparatus administered by Jewish Agency and Mossad Le'Aliyah agents sent from Israel, organized the migration of over 60,000 Moroccan Jews to Israel. Jewish emigration increased significantly in the period before Moroccan independence in 1956.

In 1951, Israel applied restrictions the migration of poor Moroccan Jews through a criterion known as seleqṣeya (Hebrew: סלקציה[23]) that included a strict medical examination and privileged healthy young people and families with a breadwinner.[24]

Reign of Hassan II (1961–1999)

Under Hassan II's reign, the topic of Israel remained highly controversial within Morocco, leading to all contacts and negotiations with the Israeli state being conducted clandestinely and away from public scrutiny.

ha-Misgeret 'The Framework'

In 1955, the Mossad, especially David Ben-Gurion and Isser Harel, established ha-Misgeret (המסגרת 'The Framework'), a clandestine, underground Zionist militia and organization in Morocco headed by Shlomo Havilio ('Louis').[25][26] Its agents were European and Israeli Jews, and it served as Mossad's base in Morocco.[25] An 'Ulpan' kindergarten for teaching Hebrew in Casablanca established in 1954 by Yehudit Galili, an envoy of the Jewish Agency, would serve as a hiding place for weapons of ha-Misgeret.[27] Galili herself would join and serve ha-Misgeret as a spy and recruiter.[27] After Moroccan independence in 1956, through an agreement between Isser Harel of the Mossad and Shlomo Zalman Shragai of the Jewish Agency, the two organizations would organize the clandestine migration of Moroccan Jews by land and by sea.[25]

Operation Yachin (1961–1964)

From 1961 to 1964, almost 90,000 Moroccan Jews were migrated to Israel in Operation Yachin, an Israeli-led initiative in which the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society paid King Hassan II a sum per capita for each Moroccan Jew who migrated to Israel.[18]

1965 Arab League Summit

In the 1965 Arab League Summit in Casablanca, Hassan II allegedly invited Israeli spies from Shin Bet and Mossad to spy on the other Arab leaders' activities, thus was instrumental in causing the Arabs' defeat to Israel in the 1967 Six-Day War.[28]

In contrast, during the Yom Kippur War, Morocco supported the Arab coalition by sending an expeditionary force of 5,500 men to the Golan and the Sinai.[29]

During 1980s, Hassan II attempted to break the deadlock to recognize Israel by meeting with Israeli prime minister Shimon Peres in Rabat in 1986, but was met with backlash and protests from the Arab League and Moroccans alike, forcing Hassan II to withdraw his attempt.[30] Nonetheless, Hassan II maintained a bond with Peres, and Peres voiced his condolences when Hassan II died in 1999.[31] According to The New York Times some diplomats said [32] the Moroccan king's initiative to meet Mr. Peres, was the product of several factors. One factor, they said, was that King Hassan was increasingly frustrated by the lack of progress in the Middle East peace process, which has been stalemated. Even more important, diplomats said, was King Hassan's unsuccessful efforts to convene an Arab summit meeting here, despite months of maneuvering and overtures to ''moderate'' Arab leaders.

Reign of Mohammed VI (1999–present)

.jpg)

Like late Hassan II, his son King Mohammed VI of Morocco, whose reign began in 1999, maintained unofficial relations with Israel. Mohammed VI's advisor, André Azoulay, is an instrumental Jewish Moroccan who facilitated the growth of Morocco in both economic and political terms.[33]

Morocco also attempted to solve the Israeli–Palestinian conflict by dispatching another Jewish aide close to Israel, Sam Ben Shitrit, to solve the conflict and make peace between the two.[34]

The two countries established low-level diplomatic relations during the 1990s following Israel's interim peace accords with the Palestinian Authority. Until the early 2000s, Morocco operated a liaison office in Tel Aviv and Israel one in Rabat, until they both were closed during the Second Intifada.[35][36][37] The two countries have maintained informal ties since then, with an estimated 50,000 Israelis traveling to Morocco each year on trips to learn about the Jewish community and retrace their family histories.[38]

Due to the growing anti-Iranian sentiment on both sides, as both countries have problems with the Iranian regime led by conservative Islamists, Morocco and Israel have sought to make their ties closer. Both countries participated in the US-led February 2019 Warsaw Conference, aimed to be anti-Iranian.[39]

In January 2020, Morocco received three Israeli drones as part of a $48 million arms deal.[40]

Israel–Morocco normalization agreement

.jpg)

Morocco recognizes Israeli sovereignty

In September 2020, U.S. president Donald Trump announced he was seeking direct flights between Rabat and Tel Aviv.[41]

On 10 December 2020, Donald Trump announced that Israel and Morocco had agreed to establish full diplomatic relations.[5] Morocco then communicated to Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu its recognition of Israel.[4] As part of the agreement, the United States agreed to recognize Morocco's Annexation of Western Sahara while urging the parties to "negotiate a mutually acceptable solution" using Morocco's autonomy plan as the only framework. Joint Declaration of the Kingdom of Morocco, the United States of America and the State of Israel was signed on 22 December 2020.[42]

On 22 December, El Al launched the first direct commercial flight between Israel and Morocco following the normalization agreement. Senior advisor to the U.S. president Jared Kushner and Israel's national security advisor Meir Ben-Shabbat were among the high-level officials on board the flight.[43]

On 25 July 2021, two Israeli carriers launched direct commercial flights to Marrakesh from Tel Aviv.[44] On 11 August 2021, Morocco and Israel signed three accords on political consultations, aviation and culture.[45] In November 2021, Morocco and Israel signed a defense agreement.[46]

Israeli president Isaac Herzog and King Mohammed VI began a correspondence after the normalization of relations. Herzog sent King Mohammed a letter during Foreign Minister Yair Lapid’s visit to Morocco, and the King replied in August 2021 with a letter in which he wrote: “I am convinced that we shall make this momentum sustainable in order to promote the prospects of peace for all peoples in the region.”[47] Herzog also sent condolences to King Mohammed after the tragic death of the little boy Rayan, who died after falling down a well, prompting a high-profile rescue effort.[48]

In 2022, Israel and Morocco agreed to cooperate on sustainable agriculture, and aimed to boost ties in tech.[49][50][51] The following year, the two countries agreed to cooperate on desalination and food security projects,[52] signed an MOU to collaborate on aeronautics and Artificial intelligence,[53] aimed to boost bilateral cooperation in the fields of innovation and scientific research,[54] and aimed for closer military and cybersecurity ties.[55][56]

On May 29, 2023, Miri Regev visited Morocco in an official capacity as the Israeli Transport Minister, marking the first trip by an Israeli Transport Minister to the North African nation.[57] Regev's trip had a personal dimension as her father was born in Morocco, and she planned to light a candle at her late grandfather’s grave in tribute to her Moroccan heritage.[58] The visit drew controversy from several political parties, such as the Democratic Federation of Leftists (FGD), the Party of Progress and Socialism (PPS), and the Justice and Development Party (PJD), due to their opposition to normalizing relations with Israel.[59] During her visit, Regev met her Moroccan counterpart, Mohammed Abdeljalil, the Minister of Transport and Logistics. They signed three agreements focused on transport cooperation, including mutual recognition of driving licenses, fostering direct maritime transport, and enhancing collaboration on road safety measures and innovation.[60]

Israel recognizes Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara

On July 17, 2023, Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu recognized Morocco's sovereignty over the Western Sahara in a letter to King Mohammed VI.[61] Netanyahu stated that Israel's decision would be applied in all relevant governmental actions and communicated to the United Nations, regional and international organizations, and all countries with which Israel has diplomatic relations. He also expressed a favorable consideration for opening a consulate in the city of Dakhla, located in the Western Sahara.[62][63]

In September 2023, it was announced that in a historic first, the head of Morocco's Senate, Enaam Mayara, would visit the Israeli Knesset on September 7.[64]

Gaza war

On 6 April 2025, tens of thousands of Moroccans participated in one of the largest demonstrations in Rabat in months, protesting against Israel’s ongoing military campaign in Gaza and expressing strong opposition to U.S. support for the war. The protestors condemned the normalization of Israel–Morocco relations, established under the 2020 Abraham Accords, and criticized recent proposals by U.S. officials to forcibly relocate Palestinians as part of Gaza’s reconstruction. Public anger in Morocco has intensified amid rising Palestinian casualties and widespread displacement.[65]

Moroccan Jewish community

Jews have a long historical presence in Morocco, where they are presently the largest Jewish community in the Arab world. The Moroccan government has tolerated its Jewish community, even after the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, facilitating the secret tie between Israel and Morocco. Moroccan-organized Jewish emigration to Israel continued while the kingdom still managed to maintain strong ties with the Israeli government through its remaining Jews.[66] Moroccan mellahs (Jewish Quarters) also exist in some cities.

Morocco is the only Arab nation to have a Jewish museum, which has been praised by Moroccans and Jewish communities alike. A large community of Moroccan Jews live around the world.[67]

Post-normalization relationship

Military rapprochement

In July 2022, it was the first time that the Chief of the Israeli Army, Aviv Kochavi, made an official visit to Morocco, strengthening their strategic and military alliance.[68]

In June 2023, Israel participated for the first time in the African Lion military manoeuvres. According to the Israeli military spokesperson, "A delegation of 12 soldiers and officers from the Golani Reconnaissance Battalion left Israel on Sunday to take part in the African Lion 2023 manoeuvres, which are taking place in Morocco".[69] However, the previous year, the Israeli army participated in African Lion as international military observers, which means that its soldiers did not take part in the exercises.[70]

Official visits

On June 7, 2023, Amir Ohana (himself of Moroccan origin), the leader of the Israeli parliament affiliated with Likud (a right-wing party), made the first official visit to the Moroccan parliament, marking a historic milestone as the first visit to a Muslim country.[71] This visit took place on a symbolic date, referring to the Six-Day War, also known as the Naksa. However, there were also protests held to express opposition to this visit.[72]

See also

References

- ^ "Morocco to upgrade its Israel liaison office to embassy status". i24NEWS. July 17, 2023. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- ^ Kasraoui, Safaa (July 18, 2023). "Morocco Considers Opening of Embassy in Israel". Morocco World News. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- ^ El Atti, Basma (February 27, 2023). "Israel starts construction work of new embassy in Rabat". The New Arab. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- ^ a b "Trump announces Morocco and Israel will normalize relations". Arab News. December 10, 2020.

- ^ a b "Israel, Morocco agree to normalize relations in latest U.S.-brokered deal". reuters.com. September 11, 2020. Retrieved December 10, 2020.

- ^ "The two faces of King Hassan II". The Independent. July 25, 1999.

- ^ "A look at Israel's decades-long covert intelligence ties with Morocco". The Times of Israel. Retrieved December 4, 2022.

- ^ Mhajne, Anwar (October 31, 2018). "What it's like to travel the world as a Palestinian on an Israeli passport". Quartz.

- ^ "Israel recognises Western Sahara as part of Morocco". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- ^ "Israel recognizes Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara". AP News. July 17, 2023. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- ^ Eljechtimi, Ahmed (July 17, 2023). "Israel recognises Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara". Reuters. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- ^ Zafrani, Haïm; Zafrani, Haïm (1998). Deux mille ans de vie juive au Maroc: histoire et culture, religion et magie. Paris : [Casablanca]: Maisonneuve & Larose ; Eddif. ISBN 978-2-7068-1330-6.

- ^ Gottreich, Emily (2020). Jewish Morocco: A History from Pre-Islamic to Postcolonial Times. I.B. Tauris. doi:10.5040/9781838603601. ISBN 978-1-78076-849-6.

- ^ a b c Laskier, Michael M. (1983). "The Evolution of Zionist Activity in the Jewish Communities of Morocco, Tunisia and Algeria: 1897–1947". Studies in Zionism. 4 (2): 205–236. doi:10.1080/13531048308575844 – via Taylor & Francis Online.

- ^ Yehuda, Zvi (September 1985). "The place of Aliyah in Moroccan Jewry's conception of Zionism". Studies in Zionism. 6 (2): 199–210. doi:10.1080/13531048508575881. ISSN 0334-1771.

- ^ Baida, Jamaa (1989). "الصهيونية والمغرب" [Zionism and Morocco]. معلمة المغرب [Ma'lamat al-Maghrib] (in Arabic). pp. 5572–5574.

- ^ Cadima (Morocco), Walter de Gruyter GmbH, doi:10.1163/1878-9781_ejiw_sim_0004780, retrieved August 18, 2025

- ^ a b c Laskier, Michael M. (March 1, 1985). "Zionism and the Jewish communities of Morocco: 1956–1962". Studies in Zionism. 6: 119–138. doi:10.1080/13531048508575875. ISSN 0334-1771.

- ^ Laskier, Michael M. (1990). "Developments in the Jewish Communities of Morocco 1956-76". Middle Eastern Studies. 26 (4): 465–505. doi:10.1080/00263209008700832. ISSN 0026-3206. JSTOR 4283394.

- ^ a b c Laskier, Michael M. (March 1, 1985). "Zionism and the Jewish communities of Morocco: 1956–1962". Studies in Zionism. 6: 119–138. doi:10.1080/13531048508575875. ISSN 0334-1771.

- ^ Gottreich, Emily (2020). Jewish Morocco: A History from Pre-Islamic to Postcolonial Times. I.B. Tauris. doi:10.5040/9781838603601.ch-006. ISBN 978-1-78076-849-6.

- ^ a b c Hazkani, Shay (March 2023). ""Our Cruel Polish Brothers": Moroccan Jews between Casablanca and Wadi Salib, 1956–59". Jewish Social Studies. 28 (2): 41–74. doi:10.2979/jewisocistud.28.2.02. ISSN 1527-2028.

- ^ מלכה, חיים (1998). הסלקציה: הסלקציה וההפליה בעלייתם וקליטתם של יהודי מרוקו וצפון-אפריקה בשנים 1948-1956 (in Hebrew). ח. מלכה.

- ^ "Seleqṣeya". referenceworks. doi:10.1163/1878-9781_ejiw_sim_0019550. Retrieved September 9, 2024.

- ^ a b c Laskier, Michael M. (1990). "Developments in the Jewish Communities of Morocco 1956-76". Middle Eastern Studies. 26 (4): 465–505. doi:10.1080/00263209008700832. ISSN 0026-3206. JSTOR 4283394.

- ^ Aderet, Ofer. "The Mossad operative who formed the Jewish underground in North Africa". Haaretz.com. Archived from the original on July 14, 2024. Retrieved January 14, 2025.

- ^ a b ברם, שיר אהרון (May 11, 2023). "The Kindergarten That Became the Mossad HQ in Morocco". The Librarians. Retrieved January 14, 2025.

- ^ Bergman, Ronen (October 15, 2016). "Mossad listened in on Arab states' preparations for Six-Day War". Ynetnews. Archived from the original on March 4, 2021. Retrieved May 20, 2021.

- ^ Touchard, Laurent. "Guerre du Kippour : quand le Maroc et l'Algérie se battaient côte à côte". Jeune Afrique. Retrieved December 4, 2022.

- ^ Miller, Judith (July 23, 1986). "Peres and Hassan in Talks; Syria Breaks Moroccan Ties". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 11, 2020. Retrieved March 27, 2019.

- ^ Gregory, Joseph R. (July 24, 1999). "Hassan II of Morocco Dies at 70; A Monarch Oriented to the West". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 10, 2020. Retrieved March 27, 2019.

- ^ Miller, Judith (July 23, 1986). "Peres and Hassan in Talks; Syria Breaks Moroccan Ties". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 11, 2020. Retrieved March 27, 2019.

- ^ News, Morocco World (October 16, 2017). "André Azoulay: Audrey Azoulay 'Deservedly' Won UNESCO Chief Vote". Archived from the original on March 27, 2019. Retrieved March 27, 2019.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Wootliff, Raoul. "'Morocco's king dispatches Jewish aide to push Israeli-Palestinian talks'". www.timesofisrael.com. Archived from the original on September 22, 2020. Retrieved February 3, 2020.

- ^ "His Majesty King Mohammed VI had a phone call with the President of The United States Mr. Donald Trump". Moroccan Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Retrieved December 6, 2022.

- ^ "Moroccan team in Israel to set up liaison office: source". Al-Arabiya. December 28, 2020. Retrieved December 6, 2022.

- ^ "Morocco's envoy arrives in Israel to reopen liaison office". The Times of Israel. Retrieved December 6, 2022.

- ^ "Israel, Morocco agree to normalise relations in US-brokered deal". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on December 18, 2020. Retrieved December 19, 2020.

- ^ Koundouno, Tamba François (February 18, 2019). "Spotlight on Rumored Morocco-Israel Normalization after Alleged Secret Meeting". Archived from the original on March 27, 2019. Retrieved March 27, 2019.

- ^ "Rabat dispose enfin de ses drones israéliens". Intelligence Online (in French). January 29, 2020. Archived from the original on February 2, 2020. Retrieved February 3, 2020.

- ^ "After UAE and Bahrain deals, Trump said aiming for direct Israel-Morocco flights". Times of Israel. September 12, 2020. Archived from the original on October 8, 2020. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- ^ "Joint-Declaration-US-Morocco-Israel" (PDF). www.state.gov.

- ^ "First Israel-Morocco Direct Commercial Flight Takes Off". Barron's. December 22, 2020. Archived from the original on January 9, 2021. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ "Israeli airlines start direct flights to Morocco after improved ties". Reuters. July 25, 2021. Archived from the original on July 26, 2021. Retrieved July 26, 2021.

- ^ "Morocco, Israel Sign Cooperation Agreements". Asharq Al-Awsat. August 12, 2021. Archived from the original on August 13, 2021. Retrieved August 13, 2021.

- ^ Ari Gross, Judah (November 24, 2021). "In Morocco, Gantz signs Israel's first-ever defense MOU with an Arab country". The Times of Israel. Retrieved November 25, 2021.

- ^ "Moroccan King writes Herzog, hopes relations bring regional peace". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com. August 20, 2021. Retrieved August 17, 2022.

- ^ "President sends condolences to Moroccan king on death of boy Rayan in well". www.timesofisrael.com. Retrieved August 17, 2022.

- ^ "Morocco & Israel to step up cooperation in smart & green farming – The North Africa Post". Retrieved August 23, 2023.

- ^ "i24NEWS". www.i24news.tv. Retrieved August 23, 2023.

- ^ Atalayar (February 15, 2022). "Morocco and Israel strengthen cooperation in smart agriculture". Atalayar. Retrieved August 23, 2023.

- ^ Staff, The Media Line (April 30, 2023). "Morocco, Israel Collaborate on Water, Food Security Projects Amid Political Tensions". The Media Line. Retrieved August 23, 2023.

- ^ "Israel, Morocco sign MoU to build AI and Aeronautics innovation center". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com. May 23, 2023. Retrieved August 23, 2023.

- ^ "Morocco, Israel seek closer cooperation in scientific research". www.aa.com.tr. Retrieved August 23, 2023.

- ^ "Israel boosting military ties with Morocco in fields of cybersecurity, intelligence". www.aapeaceinstitute.org. Retrieved August 23, 2023.

- ^ Solomon, Ariel Ben (January 18, 2023). "Israel and Morocco bolster cybersecurity and intel ties". JNS.org. Retrieved August 23, 2023.

- ^ "Miri Regev Makes Historic Visit to Morocco". The Moroccan Times. May 3, 2023. Retrieved June 3, 2023.

- ^ "Miri Regev Connects with Moroccan Roots During Historic Visit". The Moroccan Times. May 3, 2023. Retrieved June 3, 2023.

- ^ "Miri Regev's Controversial Visit to Morocco". The Moroccan Times. May 3, 2023. Retrieved June 3, 2023.

- ^ "Historic Agreements Signed During Miri Regev's Visit to Morocco". The Moroccan Times. May 3, 2023. Retrieved June 3, 2023.

- ^ "Israel recognizes Moroccan sovereignty over Sahara". HESPRESS English - Morocco News. July 17, 2023. Retrieved July 19, 2023.

- ^ Eljechtimi, Ahmed (July 17, 2023). "Israel recognises Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara". Reuters. Retrieved July 17, 2023.

- ^ Kasraoui, Safaa. "Israel Officially Recognizes Morocco's Sovereignty Over Western Sahara". moroccoworldnews. Retrieved July 19, 2023.

- ^ Keller-Lynn, Carrie. "In first, head of Moroccan senate to make official visit to Knesset on Thursday". www.timesofisrael.com. Retrieved September 5, 2023.

- ^ "Mass protests in Morocco against Israel's war in Gaza and US support". Al Jazeera. Retrieved April 9, 2025.

- ^ "Return To Morocco - PalestineRemix". interactive.aljazeera.com. Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on November 30, 2020. Retrieved February 3, 2020.

- ^ Cohen, Alecia (November 5, 2016). "Museum of Moroccan Judaism (Jewish Museum) in Casablanca". Archived from the original on March 27, 2019. Retrieved March 27, 2019.

- ^ "Israeli army chief lands in Morocco for first visit as ties normalise". France 24. July 19, 2022. Retrieved June 10, 2023.

- ^ Rabat, Basma El Atti ــ (June 6, 2023). "Israeli soldiers join African Lion military drill in Morocco". Newarab. Retrieved June 10, 2023.

- ^ "Israel joins African military exercises in Morocco". Middle East Monitor. June 6, 2023. Retrieved June 10, 2023.

- ^ "Première visite au Maroc d'Amir Ohana, président de la Knesset – Jeune Afrique". JeuneAfrique.com (in French). June 6, 2023. Retrieved June 10, 2023.

- ^ AfricaNews (June 8, 2023). "Maroc : manifestation contre la visite du chef du Parlement israélien". Africanews (in French). Retrieved June 10, 2023.