Islam in Suriname

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 13,9% of the total population in 2012 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Commewijne · Nickerie · Wanica · Saramacca | |

| Religions | |

| Sunni Islam · Ahmadiya (including the Lahore Ahmadiyya Movement) · Other Muslim | |

| Languages | |

| Arabic (liturgical language) Surinamese Dutch · Surinamese-Javanese · Sarnami Hindustani | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Dutch Muslims · Guyanese Muslims · Trinidadian and Tobagonian Muslims · Jamaican Muslims · Antillian Muslims |

| Islam by country |

|---|

|

|

|

Islam is the third-largest religion in Suriname, representing 13.9% of the country's total population as of 2012, which is the highest percentage of Muslims in the Americas. The majority of Surinamese Muslims belong to the Sunni branch of Islam.

Some speculate that Muslims first came to Suriname as slaves from West Africa and then were converted to Christianity over time, even though there is little proof for these speculations. The ancestors of the actual Muslim population came to the country as indentured laborers from the British Raj and Dutch East Indies, from whom today most Muslims in Suriname are descended.

The forms of Islam in Suriname are strongly influenced by the culture of the regions of origin: South Asia (India, Pakistan and Afghanistan)[1] and Indonesia (Java). Apart from descent, most Surinamese Muslims also share the same culture and speak the same languages.

East-west divide

The first Javanese Muslims to come to Suriname built their mosques facing west as they did in Java. It was only until contact with Hindustani Muslims in the 1930s that people realized that Mecca is east of Suriname. This created a divide between Muslims who prayed to the east (wong ngadep ngetan) and west (wong ngadep ngulon). The east-worshipping Muslims were more orthodox in their religion, whereas those who worshipped to the west were Javanese and clung more to their traditional Javanese culture.[2]

Demographics

There are 75,053 Muslims in Suriname, according to the 2012 census.[4] This number is up from 66,307 Muslims in 2004. The share of Muslims of Indo-Surinamese descent decreased from 17% to 13% in the same period (-4%), mainly because of emigration to the Netherlands and declining fertility rates. The share of Muslims among Maroon people doubled from 0.1% to 0.2%.

| Year [5] | Suriname (population) | Muslim population | Share (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1964 | 324,893 | 63,809 | 19.6% |

| 1971 | 379,607 | 74,170 | 19.5% |

| 1980 | 355,240 | 69,713 | 19.6% |

| 2004 | 492,829 | 66,307 | 13.5% |

| 2012 | 541,638 | 75,053 | 13.9% |

Ethnic groups

Islam is the main religion among Javanese Surinamese people (67%) and the second largest religion among Indo-Surinamese people (13%) and multiracial people (8%).

| Islam by ethnic group as of 2012 | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnic group | Population | Muslims | % | |||||||||||||||

| Javanese Surinamese | 73,975 | 49,533 | 67.0% | |||||||||||||||

| Indo-Surinamese | 148,443 | 18,734 | 12.6% | |||||||||||||||

| Multiracial people | 72,340 | 5,471 | 7.6% | |||||||||||||||

| All Afro-Surinamese | 206,423 | 621 | 0.3% | |||||||||||||||

| Amerindians | 20,344 | 138 | 0.7% | |||||||||||||||

| Chinese Surinamese | 7,885 | 112 | 1.4% | |||||||||||||||

| White Surinamese | 1,665 | 32 | 1.9% | |||||||||||||||

| Others and indefinable | 10,561 | 412 | 3.9% | |||||||||||||||

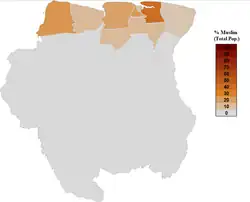

Geographical distribution

Commewijne District has the highest share of Muslims (mostly Javanese Surinamese), followed by Nickerie District and Wanica District (mostly Indo-Surinamese).

| Share of Muslims by district according to 2004 Census | |

|---|---|

| District | Percent of Muslims |

| Commewijne District | 40.4% |

| Nickerie | 22.5% |

| Wanica | 21.7% |

| Saramacca | 18.8% |

| Para | 11.3% |

| Coronie | 11.0% |

| Paramaribo | 9.4% |

| Marowijne | 6.8% |

| Brokopondo | 0.2% |

| Sipaliwini | 0.1% |

| Suriname | 13.5% |

Muslim World

Suriname (since 1996) and Guyana (since 1998) are the only countries in the Americas which are member states of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation.[6]

Notable Muslims

- Rashied Doekhi, politician

- Iding Soemita, politician

- Paul Somohardjo, politician

- Janey Tetary, indentured labourer, rebellion leader and resistance fighter

See also

- Latin American Muslims

- Latino Muslims

- Islam in Guyana

- Religion in Suriname

- Hinduism in Suriname

- Organisation of Islamic Cooperation

References

- ^ "The Afghan Muslims of Guyana and Suriname". www.guyana.org. Archived from the original on 10 April 2003. Retrieved 13 August 2025.

- ^ Hoefte, Rosemarijn (2015). "Locating Mecca: Religious and Political Discord in the Javanese Community in Pre-Independence Suriname". In Yelvington, Kevin A.; Khan, Aisha (eds.). Islam and the Americas. University Press of Florida. pp. 69–91. ISBN 978-0-8130-6013-2.

- ^ "Censusstatistieken 2004" (PDF). Algemeen Bureau voor de Statistiek. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

- ^ "Algemeen Bureau voor de Statistiek" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 January 2025.

- ^ Kettani, Houssain. "Muslim Population in the Americas: 1950 –2020". International Journal of Environmental Science and Development. 1 (2): 127–135. doi:10.18178/ijesd. eISSN 2010-0264. ISSN 2972-3698.

- ^ "Member States of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation". Archived from the original on 9 December 2013. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- "Mirza Ghulam Ahmad and the Qadiyani Sect : Imaam al-Albaanee". AbdurRahman.Org. 15 January 2014. Retrieved 15 August 2024.

Further reading

- Bal, Ellen; Kathinka Sinha-Kerkhoff (August 2005). "Muslims in Surinam and the Netherlands, and the divided homeland" (PDF). Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs. 25 (2): 193–217. doi:10.1080/13602000500350637. hdl:1871/33761. S2CID 18379751.

- Chickrie, Raymond S. (1 March 2011). "Muslims in Suriname: Facing Triumphs and Challenges in a Plural Society". Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs. 31 (1): 79–99. doi:10.1080/13602004.2011.556890. ISSN 1360-2004.

- Chitwood, Ken (2017), "Islam in Suriname", Encyclopedia of Latin American Religions, Springer, Cham, pp. 1–2, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-08956-0_266-1, ISBN 978-3-319-08956-0, retrieved 13 August 2025

- Hassankhan, Maurits S.; Vahed, Goolam; Roopnarine, Lomarsh, eds. (10 November 2016). Indentured Muslims in the Diaspora: Identity and Belonging of Minority Groups in Plural Societies (0 ed.). Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315272030-6. ISBN 978-1-315-27203-0.

- "Islam and Indian Muslims in Suriname: A Struggle for Survival". Taylor & Francis. 10 November 2016. doi:10.4324/9781315272030-6/islam-indian-muslims-suriname-struggle-survival-maurits-hassankhan. Archived from the original on 10 May 2025.

- Prins, J. (1 January 1961). "De islam in Suriname : een orientatie". New West Indian Guide / Nieuwe West-Indische Gids. 41 (1): 14–37. doi:10.1163/22134360-90002335. ISSN 2213-4360.

- McLennan, John D.; Afifi, Tracie O.; MacMillan, Harriet L.; Warriyar K.V., Vineetha (1 September 2024). "Is religious affiliation associated with parent disciplinary behavior in Suriname and Guyana". Child Abuse & Neglect. 155: 106960. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2024.106960. ISSN 0145-2134.

- Khan, Aisha (10 January 2017). Islam and the Americas. University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-0-8130-5994-5.