Integrated coastal zone management

Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM), also known as Integrated Coastal Management (ICM) or Integrated Coastal Planning, is a coastal management decision-making process that manages all aspects of the coastal zone, including geographical and political boundaries, in an attempt to achieve sustainability. This notion was conceptualized in 1992 during the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro. The specifics regarding ICZM are outlined in the proceedings of the summit within Agenda 21, Chapter 17.[1]

Overview

Framework

Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) is a decision-making framework designed to address the diverse and region-specific environmental needs of national, regional, and local coastal zones by considering the interactions between natural, social, and economic systems in coastal areas. ICZM is applied within a clearly defined geographical area, typically characterized by overlapping jurisdictions and environmental pressures, and requires a high level of integration across sectors, stakeholders, and governance levels in order to ensure sustainable coastal development.[2]

Importance

Significance and management of coastal zones

Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) is suitable for sustainable development of coastal zones; however, it may not be adapted to all cases.[3] For example, the Sumatra earthquake and the Indian Ocean tsunami had significant impacts on the coastal environment itself and has altered perceptions of coastal hazard mitigation.[4]

Coastal zones are often characterized by diverse and productive ecosystems of great importance to human populations.[5] Coastal margins equate to only 8% of the world's surface area but provide 25% of global productivity. Approximately 70% of the world's population lives within a day's walk of the coast,[6] and two-thirds of the world's cities are coastal.[7]

Resources such as fish and minerals are in high demand among coastal dwellers for subsistence, recreation, and economic development.[8] As these resources are considered common property, they have been subjected to intensive and specific exploitation. For example, 90% of the world's fish harvest comes from within national exclusive economic zones, most of which are within sight of the shore.[6] Substantial, potentially unsustainable quantities of resources are often extracted, and the impacts of extractive activity are compounded by pollution, contributing to the cumulative degradation of these ecosystems.

Goals

For ICZM to be successful, it must adhere to sustainability principles and act upon them in an integrated fashion. A balance between environmental protection and economic/social development is paramount.[9] ICZM considers the spatial, functional, legal, policy, knowledge, and participation components of coastal management, among other items.[10] The four identified goals of ICZM are:

- Maintaining the functional integrity of coastal resource systems.

- Reducing resource-use conflicts.

- Maintaining environmental health.

- Facilitating economic development.[2]

Five-step process

- Problem and needs assessment: Issues need to be identified and quantified. This first step will require co-operation among government, local and regional non-governmental entities, and local residents.

- Plan: After the issues and problems have been identified and weighted, an effective management plan that can act as a guide for future development is developed. The plan will be specific to the area in question.

- Institutionalization of plan: Plan adoption by relevant agencies is carried out, either in the form of legally binding statutory plans, strategies, or objectives, or as non-statutory agency guidance or policy. [11]

- Implementation: The plan is put into effect through law enforcement, education, development, etc. The implementation activities are unique to their environments and can take many forms.

- Evaluation: The last phase is evaluation of the plan's implementation. The principles of sustainability mean that there is no ‘end state.’ ICZM is an ongoing process constantly readjusting the equilibrium between economic development and environmental protection. Feedback is a crucial part of the process, enabling continued effectiveness even if the situation changes.

Public participation and stakeholder involvement are essential in ICZM processes, not only from a democratic perspective but also from a technical and instrumental standpoint, to reduce decision-making conflicts.

Dimensions of coastal zone management

Defining coastal zones

Defining the coastal zone is of particular importance to the idea of ICZM. Ketchum (1972)[12] defined the area as:

The coastal zone refers to the band of dry land and the adjacent ocean space—including both the water column and the submerged land—where terrestrial processes and land uses directly influence oceanic processes and activities, and vice versa. The diverse characteristics of coastal regions, combined with the varying spatial scales of interacting systems, present considerable challenges for effective management. As dynamic environments shaped by global and local drivers, coasts are influenced by processes such as river systems, which often extend far inland and add to the complexity of coastal dynamics. These complexities complicate the delineation of hinterlands and hinder the development of coherent and effective management strategies.

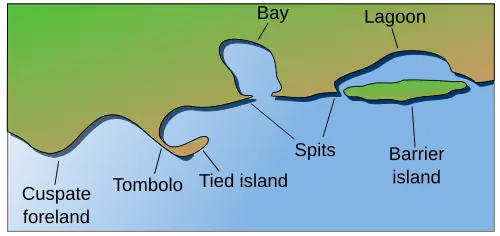

In addition to their physical characteristics, coastal zones encompass ecosystems, resources, and human activities, the latter being a primary driver of disruption to natural coastal systems. Management is further complicated by the use of administrative boundaries, which often rely on arbitrary lines that fragment the zone. This fragmented approach can result in management strategies that focus on individual sectors, such as land use or fisheries, potentially causing negative impacts in other sectors.

Finding sustainable solutions

The concept behind ICZM is sustainability. For ICZM to succeed, it must be sustainable. Sustainability entails a continuous decision-making process, so there is never an end-state, just a readjustment of the equilibrium between development and environmental protection.[13] The concept of sustainability or sustainable development came to fruition in the 1987 World Commission on Environment and Development's report, Our Common Future. It stated sustainable development is “to meet the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”[14]

Three main points:

- Economic development to improve the quality of life of people

- Environmentally appropriate development

- Equitable development[13]

Sustainability entails recognizing the right of all people to lead healthy and productive lives. It emphasizes the equitable distribution of benefits across society while safeguarding the environment through the responsible and appropriate use of natural resources.[13]

Sustainability is not defined by a fixed set of prescriptive actions but rather represents a way of thinking. Adopting this perspective fosters a long-term and holistic approach, a quality that effective Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) seeks to achieve.[11]

Finding integration and synergies

The concept of integration can be applied to a wide range of contexts; therefore, it is important to define the term specifically within the framework of coastal zone management to understand the objectives of Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM). Within ICZM, integration takes place across and between multiple levels. Five principal forms of integration are generally recognized:[13]

- Integration among sectors: A wide range of sectors operate within the coastal environment, with human activities primarily centered on economic pursuits such as tourism, fisheries, and port operations. Sectoral integration within Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) requires cooperation among these sectors, built on the recognition of shared goals related to sustainability and mutual acknowledgment of each sector’s role within the coastal area.

- Integration between land and water elements of the coastal zone: Spatial integration within Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) reflects the understanding that the coastal environment functions as an interconnected whole. The coastal zone is shaped by dynamic and interdependent processes, where changes imposed on one system or feature inevitably generate cascading effects across others. Recognizing these relationships is fundamental to achieving coherent and sustainable management outcomes.

- Integration among levels of government: Institutional integration within Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) emphasizes the need for consistency and cooperation across different levels of governance. ICZM is most effective when initiatives share a common purpose at local, regional, and national levels. The establishment of shared goals and coordinated actions enhances efficiency, reduces overlap, and minimizes confusion in planning and policymaking.

- Integration between nations: Temporal integration within Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) extends the scope of management beyond immediate or local concerns, recognizing its significance as a tool on a global scale. When goals and principles are aligned across supranational levels, large-scale and long-term challenges can be more effectively mitigated or even prevented.

- Integration among disciplines: Stakeholder integration within Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) requires the incorporation of knowledge and perspectives from a wide range of disciplines and communities. Scientific, cultural, traditional, political, and local expertise must all be recognized and valued. By embracing these diverse forms of knowledge, ICZM fosters a genuinely holistic approach to coastal management.

The term integration in a coastal management context has many horizontal and vertical aspects, which reflects the complexity of the task and proves a challenge to implement.

Constraints

Successful implementation is still a major challenge to the idea of ICZM.

Top-down and bottom-up approach

Major constraints of ICZM are mostly institutional, rather than technological.[10] The top-down approach in administrative decision-making considers problematization as a tool promoting ICZM through the idea of sustainability.[10] Community-based, or “bottom-up,” approaches in coastal management allow for the identification of problems and issues that are specific to local areas. A key advantage of this approach is that existing challenges are acknowledged on their own terms, rather than being forced to fit pre-established strategies or policies. Public consultation and participation are essential even within “top-down” approaches, as they enable the incorporation of local perspectives into broader policy frameworks. Prescriptive top-down methods have often failed to effectively address resource-use challenges in economically disadvantaged coastal communities, where perceptions and priorities may differ significantly from those in developed regions.[10] This results in another constraint to ICZM, the idea of common property.

Human factors

The coastal environment has historical and cultural connections with human activity. Its wealth of resources have provided for millennia. With regard to ICZM, legally binding management becomes difficult when coastal areas are perceived as common areas available to all.[6] Enforcing restrictions or changes to activities within the coastal zone can be challenging, as these resources are often critical to local livelihoods. The perception of the coast as common property can complicate top-down management approaches. Moreover, the concept of common property is inherently complex, and differing perceptions of ownership and use can contribute to the cumulative overexploitation of resources—the very issue that Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) aims to address.

Adoption

European Union

The European Parliament and the European Council "adopted in 2002 a recommendation on Integrated Coastal Zone Management which defines the principles sound coastal planning and management. These include the need to base planning on sound and shared knowledge, the need to take a long-term and cross-sector perspective, to pro-actively involve stakeholders and the need to take into account both the terrestrial and the marine components of the coastal zone".[15]

Iran

The development of comprehensive management plans for the optimal utilization of existing resources and potentials is a key approach for the sustainable and long-term use of natural, human, and financial assets in both developed and developing countries. The versatility and economic value of coastal resources have attracted participation from both private and governmental actors seeking to maximize profits. Consequently, the preparation and implementation of management plans to ensure the enduring and sustainable use of coastal resources have become essential.

Iran, with approximately 6,000 km of coastline along its northern and southern borders, possesses substantial economic potential in its coastal zones. Given the ecological diversity of these areas and the range of coastal activities and operators, attention to Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) is particularly significant. This importance is reinforced by legal frameworks, including the ratification of Arrangements No. 40 from the Transportation Chapter of the Third Schedule and Article No. 63 of the Fourth Economic, Social, and Cultural Schedule, along with their corresponding executive regulations, which provide formal support for ICZM implementation.

The General Directorate of Coasts and Ports Engineering within the Ports and Maritime Organization was tasked with incorporating Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) studies. The first phase of these studies commenced in spring 2003 and concluded in autumn 2006. The results of this phase were documented in a series of reports prepared by a team of national and international experts.

- 1- Project Methodology

- 2- Scrutinized scope of services related to studies

- 3- Investigation of studies' needs and project preparation and performance

- 4- Study, definition and determination of Iranian coastal zone boundaries

- 6- Investigation of International concepts, methods and experiences about Integrated Coastal Zone Management

- 7- Study and investigation of different features of Integrated Coastal Zone Management in Iran

- 8- Preparation and designation of geographic database

- 9- Purchasing and preparing basic data

The second phase of ICZM studies began in autumn 2005 and has since been completed and presented. This phase involved the work of six Iranian consultants, who, with the support of international experts, were responsible for producing eleven reports detailing the findings and outcomes of the study.[16]

Mediterranean

At the Conference of Plenipotentiaries on the ICZM Protocol, held on 20–21 January 2008 in Madrid, the ICZM Protocol was officially signed. Presided over by H.E. Ms. Cristina Narbona Ruiz, the Minister of Environment of Spain, fourteen Contracting Parties to the Barcelona Convention endorsed the Protocol: Algeria, Croatia, France, Greece, Israel, Italy, Malta, Monaco, Montenegro, Morocco, Slovenia, Spain, Syria, and Tunisia. The remaining Parties announced their intention to sign in the near future. This Protocol represents the seventh instrument adopted under the Barcelona Convention. The decision to approve the draft text and recommend it for signature at the Conference of Plenipotentiaries was made during the 15th Ordinary Meeting of the Contracting Parties, held in Almería from 15–18 January 2008. All the parties are convinced that this Protocol is a crucial milestone in the history of the Mediterranean Action Plan of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP/MAP), the first-ever Regional Seas Programme under UNEP's umbrella. It will allow the countries to better manage their coastal zones, as well as to deal with the emerging coastal environmental challenges, such as climate change.

The ICZM Protocol is a unique legal instrument in the entire international community and the Mediterranean countries are proud of this fact. The Contracting Parties expressed their willingness to share their experiences with other coastal countries worldwide. The signing of the ICZM Protocol followed six years of dedicated work by all Parties. Syria became the sixth country to ratify the Protocol, with the President of the Syrian Arab Republic issuing Legislative Decree No. 85 on 31 September 2010. Following this ratification, the ICZM Protocol officially entered into force one month later, upon Syria’s deposit of the instrument of ratification with the depositary country, Spain. In September 2012, Croatia and Morocco ratified the Protocol, bringing the total number of ratifications to nine. (Slovenia, Montenegro, Albania, Spain, France, the European Union, Syria, Croatia, and Morocco).

The Action Plan for the implementation of the ICZM Protocol 2012-2019 was adopted on the occasion of the CoP 17, held in Paris from 8 to 10 February 2012. The core purposes and objectives of this Action Plan are to implement the Protocol based on country-based planning and regional co-ordination, namely:

- Support the effective implementation of the ICZM Protocol at regional, national, and local levels, including through a Common Regional Framework for ICZM;

- Strengthen the capacities of Contracting Parties to implement the Protocol and use in an effective manner ICZM policies, instruments, tools, and processes; and

- Promote the ICZM Protocol and its implementation within the region and globally by developing synergies with relevant Conventions and Agreements.

A roadmap for the implementation of the ICZM Process, prepared by Priority Actions Programme Regional Activity Centre (PAP/RAC), is available on the Coastal Wiki platform of the PEGASO and ENCORA projects: ICZM Process.

On May 8, 2014, the Israeli Government ratified the ICZM Protocol. This Resolution (#1588) was made in accordance with Article 19(b) of the Government Rules of Procedure. The ICZM Protocol ratification by Israel brought the number of ratifications to 10.

New Zealand

New Zealand is unique as it uses sustainable management within legislation, with a high level of importance placed on the coastal environment.[5] The Resource Management Act (RMA) (1991) promoted sustainable development and mandated the preparation of a New Zealand Coastal Policy Statement (NZCPS), a national framework for coastal planning. It is the only national policy statement that was mandatory.[17] All subsequent planning must not be inconsistent with the NZCPS, making it a very important document.[5] Regional authorities are required to produce regional coastal policy plans under the RMA (1991) but they only need to include the marine environment seaward of the mean high-water mark. However, many regional councils have chosen to integrate the ‘dry’ landward area within their plans, breaking down the artificial barriers.[5] This attempt at ICZM is still in its early days, running into many legislative hurdles, and is yet to achieve a fully ecosystems-based approach. But as part of ICZM, evaluation and adoption of changes is important and ongoing changes to the NZCPS in the form of reviews is currently happening.[17] This will provide a stepping stone for future initiatives and the development of a fully integrated form of coastal management.

See also

- Coastal management, to prevent coastal erosion and creation of beach

References

- ^ "Agenda 21" (PDF).

- ^ a b THIA-ENG, C. 1993. Essential Elements of Integrated Coastal Zone Management. Ocean and Coastal Management, 21, 81-108.

- ^ Billé, Raphaël (2008-11-27). "Integrated Coastal Zone Management: four entrenched illusions". S.A.P.I.EN.S. (1.2). ISSN 1993-3800.

- ^ Kurt Fedra. 2008. Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM). Singapore: Research Publishing Services.

- ^ a b c d KAY, R. & ALDER, J. 1999. Coastal Planning and Management, London, E & FN Spon.

- ^ a b c BROWN, K., TOMPKINS, E. L. & ADGER, N. 2002. Making Waves: Integrating coastal conservation and development, London, Earthscan Publications Limited.

- ^ CROOKS, S. & TURNER, R. K. 1999. Integrated coastal management: sustaining estuarine natural resources. Advances in Ecological Research, 29, 241-289.

- ^ BERKES, F. 1989. Common property resources: Ecology and community-based sustainable development, London.

- ^ CICIN-SAIN, B. & KNECHT, R. 1998. Integrated coastal and ocean management: concepts and practices. Washington D.C.: Island Press.

- ^ a b c d IDRUS, M. R. 2009. Hard Habits to Break: Investigating Coastal Resource Utilisations and Management Systems in Sulawesi, Indonesia Doctor of Philosophy in Environmental Science, University of Canterbury.

- ^ a b MASSELINK, G. & HUGHES, M. 2003. Introduction to Coastal Processes and Geomorphology, London, Hodder Arnold.

- ^ KETCHUM, B. H. 1972. The water's edge: critical problems of the coastal zone. In: Coastal Zone Workshop, 22 May-3 June 1972 Woods Hole, Massachusetts. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- ^ a b c d CICIN-SAIN, B. 1993. Sustainable Development and Integrated Coastal Management. Ocean and Coastal Management, 21, 11-43.

- ^ WORLD, COMMISSION, ON, ENVIRONMENT, AND & DEVELOPMENT 1987. Towards Sustainable future, "Our common future". New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ "Integrated Coastal Management - Environment - European Commission".

- ^ Portal of the Iran ICZM

- ^ a b PEART, R. 2007. Beyond the Tide: Integrating the management of New Zealand's coasts, Auckland, Environmental Defence Society

External links

- European Commission Coastal Zone Policy

- ENCORA Coastal WIKI -EU Coordination Action on ICZM

- Overview ICZM courses in Europe

- Examining Best Practices in Coastal Zone Planning Lessons and Applications for British Columbia's Central Coast

- Coastal Zone Management Policy and Politics Class Archived 2009-03-24 at the Wayback Machine

- Safecoast Knowledge exchange on coastal flooding and climate change in the North Sea region

- ICZM principles Archived 2007-07-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ZonaCostera | KüstenZone | CoastalZone Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine | FrangeCôtière | KustStrook: Wiki in development with relevant and on-time information, useful for the integrated management of the coastal zones of our world. Integrated development is everybody's business!

- EUCC Marine Team: ICZM in Europe

- Coastal Zone Management Unit in Barbados

- Integrated Coastal Zone Management in Iran

- Integrated coastal zone management (ICZM) is a dynamic

- Videos