Inland Steel Building

| Inland Steel Building | |

|---|---|

Inland Steel Building in May 2007 | |

| General information | |

| Location | 30 W. Monroe Street[1] Chicago, Illinois |

| Coordinates | 41°52′52″N 87°37′45″W / 41.8810°N 87.6291°W |

| Construction started | 1956 |

| Opening | February 3, 1958 |

| Owner | New York Life Insurance Company |

| Height | |

| Roof | 332 feet (101.2 m)[2] |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 19 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Bruce Graham and Walter Netsch of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill |

| Developer | Inland Steel |

| Structural engineer | Skidmore, Owings & Merrill |

Inland Steel Building | |

| |

| Location | 30 W. Monroe St., Chicago, Illinois |

| Coordinates | 41°52′51″N 87°37′43″W / 41.88083°N 87.62861°W |

| Area | 0.5 acres (0.2 ha) |

| Built | 1958 |

| Architect | Skidmore, Owings & Merrill; Graham, Bruce & Walter Netsch |

| Architectural style | International Style |

| NRHP reference No. | 09000024[3] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | February 18, 2009 |

| Designated CL | October 7, 1998[4] |

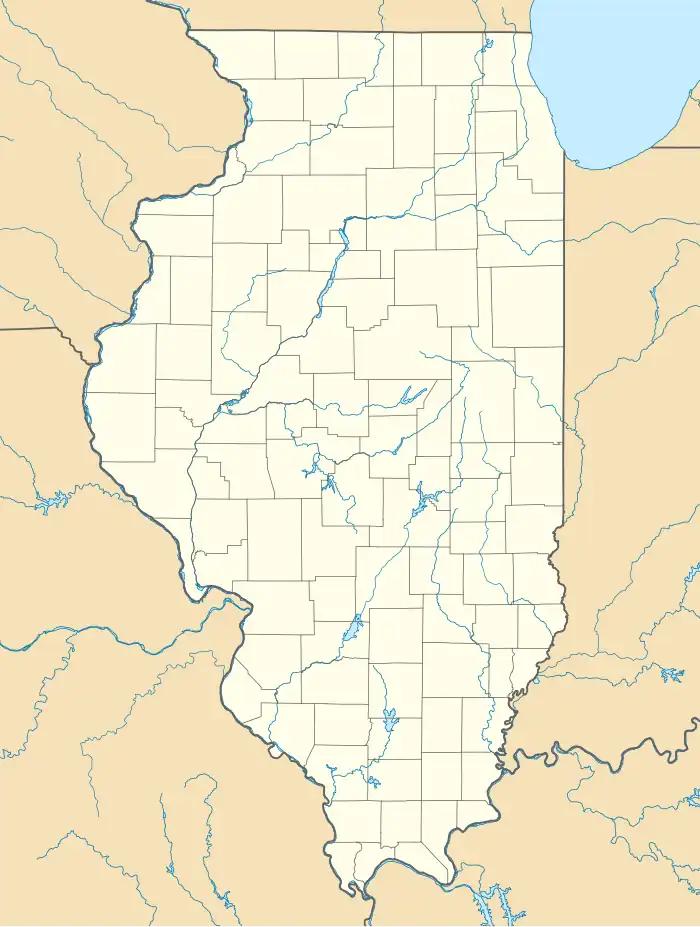

The Inland Steel Building is a 332-foot-tall (101 m) skyscraper at 30 West Monroe Street in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Constructed from 1956 to 1958, the building was designed by Bruce Graham and Walter Netsch of the architectural firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM) in the International Style. It was originally the headquarters of the Inland Steel Company and was one of the first skyscrapers to be built in the Chicago Loop since World War II. The Inland Steel Building is designated a Chicago Landmark and on the National Register of Historic Places.

Inland Steel decided to develop the building because of space constraints in its previous headquarters, the First National Bank Building. In August 1954, Inland Steel announced plans to lease a site at Monroe and Dearborn streets from the Chicago Board of Education. SOM prepared plans for the site, which were announced in March 1955, and work began in January 1956. The building was nearly fully leased before it opened on February 3, 1958. Inland Steel owned the building until the late 1980s and eventually came to occupy two-thirds of the space. After a Japanese firm briefly owned the building, JP Interests acquired it in 1989 and conducted renovations. Following another change of ownership, a syndicate that included the architect Frank Gehry bought the building in 2005 and resold it in 2007 to Capital Properties, which conducted another renovation. The New York Life Insurance Company seized ownership in 2025.

The Inland Steel Building consists of two distinct masses: a 19-story main structure at the corner of Monroe and Dearborn, and a 25-story mechanical tower to the east. The main building's facade consists of a curtain wall with green-tinted glass and stainless steel spandrel panels, columns, and mullions. The facade's columns carry the building's entire weight, allowing the majority of the spaces inside to be designed without any interior columns. The first two stories are recessed from ground level, while the upper stories were largely designed as offices with a modular floor grid and movable partitions. There was also a dining suite on the 13th floor and an executive suite on the 19th floor. The mechanical tower contains all the stairs, elevators, and mechanical ducts. Over the years, the building has received praise for its design and materials, and its architecture, while not widely copied, has influenced the design of other buildings.

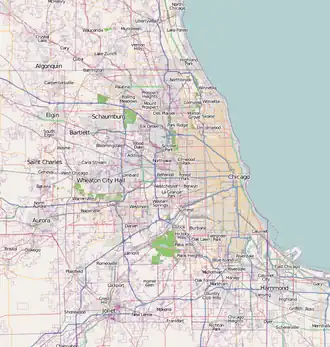

Site

The Inland Steel Building is located at 30 West Monroe Street,[5][6] at the northeast corner with Dearborn Street, in the Loop community area of Chicago, Illinois, United States.[7] The site spans about 28,000 square feet (2,600 m2),[8] measuring 120 feet (37 m) along Monroe Street to the south and 192 feet (59 m) along Dearborn Street to the west.[9][10] It occupies the southwestern corner of a city block bounded by Dearborn and Monroe streets, along with State Street to the east and Madison Street to the north. The structure shares the block with One South Dearborn to the north and the CIBC Theatre to the east.[11] When the Inland Steel Building was constructed in the late 1950s, there was another building directly abutting the north facade, but this was replaced with a plaza when One South Dearborn was built in the 2000s.[12] The building also originally shared the block with the former McVicker's Theater on Madison Street.[13]

Prior to the Inland Steel Building's construction, the entire block was owned by the Chicago Board of Education. When the region was divided into townships in the 19th century, a small amount of land in each township was reserved for school usage; the Board of Education decided to lease out the land it owned in the Loop, rather than build a school there.[14] The corner of Monroe and Dearborn contained the Crilly Building, a seven-story building[9][15] that dated from 1878 and housed the Chicago Stock Exchange.[16] The Crilly Building was an early example of a structure that partially incorporated a steel frame, making it a precursor to the early skyscraper.[17] The northern section previously had two seven-story buildings dating from 1888, which contained the Chicago Evening Journal headquarters and the Saratoga Hotel.[8][16] These were shortened to three stories with the construction of a restaurant at 27 South Dearborn Street in 1948.[16] The restaurant structure was two stories high.[17]

History

The building's namesake, the Inland Steel Company, had opened its first Chicago office at the Marquette Building in 1898.[18] The company relocated in 1904 to the First National Bank Building at Monroe and Dearborn.[18][19] By the 1950s, Inland Steel had two floors on the First National Bank Building.[18][20] The company's post–World War II growth prompted its president Clarence B. Randall to establish a committee to consider plans for expanding the offices.[18][21] At the time, the company could not lease any more space in the First National Bank Building, which was fully occupied.[18] After some consideration, the committee recommended a brand-new structure for Inland Steel's Chicago headquarters,[21][22] which would be able to accommodate the future growth of Inland Steel's office staff.[23] Leigh Block, president of Inland Steel, said: "We wanted a building we'd be proud of, one that spelled steel."[24][25]

Development

Planning

By 1954, Inland Steel was interested in erecting its own office building on the block bounded by Dearborn, Monroe, State, and Madison streets. Inland Steel wanted to lease the corner of Monroe and Dearborn from the Board of Education, but the existing leases there did not expire for 31 years.[20] That August, Inland Steel officially announced plans to lease the site and erect the building there.[26][27] The firm of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM) drew up the preliminary plans, which called for a 17-story office tower with 300,000 square feet (28,000 m2).[9] Randall told Nathaniel A. Owings, one of SOM's partners, that he wanted the building "to be like a man with immaculate English tailoring" and that the design should allude to the company's heritage.[25][28] Inland Steel offered to lease the site from the Board of Education for 99 years, initially paying $75,000 annually.[9][26] The Board of Education approved the lease that October, with the stipulation that Inland Steel pay $84,000 annually for the first 20 years and renegotiate the fee every decade afterward.[15][29] Since the site was exempt from property tax, Inland Steel initially paid no property taxes, saving $172,000 annually.[30]

In its annual report published in February 1955, Inland Steel announced that it would start constructing a 19-story skyscraper later that year.[31][32] The firm was to occupy the top seven stories and lease out the rest of the building.[33] The next month, SOM architect Walter Netsch unveiled plans for a building with a 23-story mechanical tower;[8] the plans called for the structure to be supported entirely by 14 exterior columns.[34][35] Inland Steel unveiled an architectural model of the skyscraper that month.[36][34] SOM initially contemplated constructing the building's garage at ground level but later decided to instead place the garage in the basement, freeing up the ground level for commercial tenants.[35] The architects also contemplated using black steel for the exterior columns, but decided against it, on the basis that it was too similar to Ludwig Mies van der Rohe's skyscrapers.[36] In exchange for constructing public space at ground level, Inland Steel was allowed to construct additional floor area under Chicago zoning code.[37]

The development of the Inland Steel Building coincided with the construction of several other office buildings in the Loop.[38][39] Though the Inland Steel Building was sometimes cited in the contemporary media as the Loop's first large tower in 20 years, and by extension the first post–World War II skyscraper in the area,[40][41] One Prudential Plaza (completed in 1955) held that distinction.[38][42] These conflicting claims stem from the fact that the term "The Loop" refers both to an area encircled by the Chicago "L", as well as Chicago's downtown in general. The Inland Steel Building was the first postwar building within the Chicago "L"'s loop, but One Prudential Plaza was the first such building downtown overall.[43][44] The Inland Steel Building was also cited as one of the first post–World War II buildings in Chicago to be designed in a modernist style.[45]

Construction

Inland Steel announced in August 1955 that it would clear the site.[16][40][46] That November, Turner Construction received the general contract to construct the building.[47][48] Work on the foundation began on January 10, 1956.[41][49] Inland Steel executives devised a system of steel supports and shoring to ensure that the excavations did not destabilize adjacent buildings or streets.[50] Contractors finished constructing the pilings for the foundations in early March;[51] each piling was drilled into the ground using a 12-short-ton (11-long-ton; 11 t) pile driver until it were embedded into the soil.[52] Fishbach, Moore & Morrissey were hired as the building's electrical contractors,[53] while the Badger Concrete Company of Wisconsin was hired to construct the wall panels.[54] The steel contract was awarded to a subsidiary of Inland Steel, Joseph T. Ryerson & Sons, which prefabricated the columns and girders.[50]

Inland Steel occupied the top eight stories.[10][55] Draper & Kramer—a real-estate firm that had occupied the Crilly Building, one of the three previous existing buildings on the site—was hired as the leasing agent, later occupying space in the skyscraper.[56] The first tenant to sign a lease was the Chicago Association of Commerce, which had leased the building's ground (first) and second stories in November 1955[33][57] and operated an exhibit space on these stories.[58] The Chicago Association of Commerce was initially the only ground-floor tenant, as Inland Steel did not want stores on that floor.[59] Other notable tenants who signed leases during construction included the financial firm White Weld & Co., which leased the 4th floor for use as a trading floor,[60][61] as well as SOM itself, which occupied two and a half floors.[62][63] The Toronto-Dominion Bank,[61] the New York Life Insurance Company, and the manufacturer A. O. Smith Corporation had space in the building as well.[62][63][64] These floors were initially leased out for 15-year terms, except for the 11th floor, which was leased for five years in case Inland Steel needed to expand its offices.[59]

The prefabrication of the steel frame helped speed up the construction process,[50][65] and the superstructure was topped out on November 1, 1956, when the last steel beam was installed.[66][67] A spruce tree was hoisted atop the structure to mark the occasion,[66] and a broom was placed on the final steel beam to celebrate the fact that no workers had died to date.[67] One worker was subsequently killed in June 1957 after being crushed in an elevator shaft;[68][69] this was the project's only fatal incident.[65] By that October, Draper & Kramer had leased out 98.5% of the space,[62][63] despite the fact that the rent was higher than at other office buildings in the area.[61][64] The building was substantially completed at the beginning of 1958,[70] and Inland Steel moved its Chicago offices there during the weekend of January 11–12, 1958.[19] Inland Steel's new offices covered 78,500 square feet (7,290 m2), slightly less than the company's 81,000-square-foot (7,500 m2) space at the First National Bank Building.[59][71] However, the Inland Steel Building offices actually had more usable space, since nearly one-fifth of the First National Bank space had been devoted to corridors.[59]

1950s to 1970s

.jpg)

The Inland Steel Building opened to the public on February 3, 1958.[64][72][73] White Weld & Co. became the first lessee to occupy space there.[72] Just after the building opened, one of its offices caught fire, breaking several windows;[74] another fire in 1959 caused damage to the 7th floor, but the fireproof design prevented the blaze from spreading.[75] By 1960, the building accommodated 1,200 office workers, in addition to 64 service staff.[23] In its first few decades, the Inland Steel Building was almost fully occupied, and real-estate brokers reportedly grew tired of trying to lease out the space.[43] The main building's facade was washed twice annually using a custom-made acidic mixture, but the attached mechanical tower was not washed for the first time until 1965.[76] The building was being included on architectural tours of the Loop's architecture by the early 1970s.[77]

The Board of Education, which still owned the Inland Steel Building's site, was considering selling the land by the mid-1970s.[78][79] Though Inland Steel's lease was valid through 2053, the leases for most of the other parcels on the block were covered by leases that expired in 1985.[14] The board subsequently sold the land under the building in 1979 to the First Federal Bank, which continued to lease the land to Inland Steel.[80] SOM, which had gradually expanded its offices in the Inland Steel Building to eight stories,[81] also moved out of the building in 1979.[43]

1980s to mid-2000s

The rent on the site had increased to $105,000 by the early 1980s.[82] and a leasing agent was appointed in 1985.[83] Inland Steel was considering selling the building by 1987, retaining some of the space under a leaseback arrangement. The sale was intended to save the city $16 million over 15 years.[84] A Japanese firm, Misawa Homes, acquired the building by the next year,[85] making it one of several properties in the Chicago Loop that were owned by Japanese firms.[86][87] JPS Interests, operated by local developer John P. Sweeney,[88] acquired the Inland Steel Building in 1989 and agreed to spend $3 million on renovations.[89] The project included refurbishing the cafeteria and windows, adding sprinklers and stainless-steel decorations, and conducting asbestos abatement.[43]

By the early 1990s, Inland Steel was by far the largest tenant, with two-thirds of the space.[43] During that decade, Ross Barney+Jankowski Architects leased a 17th-story space and renovated that floor into an architectural studio.[90] Other occupants included the Talman Home Federal Savings and Loan Association, the First National Bank of Chicago,[43] and the architectural firm HOK.[91][92] Inland Steel was acquired in 1998 by Ispat Steel, which continued to have offices in the building.[93] The firm downsized its offices, vacating large amounts of space,[94] and the owner at the time, St. Paul Travelers Cos., offered motorcycles to brokers who were able to lease out at least one full floor of space.[91] The Inland Steel Building's location, mechanical features, and open-plan floors made it particularly popular among architectural firms, who made up five of the building's tenants by 2000.[94] The structure was two-thirds occupied by 2002.[91]

A syndicate that included the architect Frank Gehry was considering buying the building for $50 million by 2005.[95][96] Gehry had first contemplated buying it after attending a party where he was erroneously told that the building was in disrepair. He partnered with several other men to acquire the structure; St. Paul Travelers Cos. refused to sell until they learned of Gehry's involvement.[97][98] At the time, the building was 95% occupied, with its largest tenants being Ispat and the architecture firm Gensler, though Ispat's lease was planned to expire the next year.[96] Gehry and his partners signed a contract to buy the building in July 2005,[99] and the sale was finalized the next month for $44.5 million.[100] Gehry initially wanted his partners to hire SOM to oversee a wide-ranging renovation, but they instead refurbished small sections of the building at a time; even this had to be postponed due to lower-than-expected income.[98] Gehry expressed disappointment in his partners' management of the structure,[98][101] and he said: "When you buy a landmark, you have a responsibility."[100]

Late 2000s to present

Capital Properties LP agreed to buy the building in July 2007[101] and finalized its purchase that November, paying $57.25 million.[102][103] The next year, Capital Properties announced that it would spend $40 million to renovate the building,[104] and Gehry was hired to oversee the renovation, collaborating with SOM.[98][105] By then, half the building was vacant.[98] The project was eligible for a federal tax abatement and a city tax credit.[98] The project was to include environmental-sustainability upgrades including a green roof, a new cooling system, and new sprinklers,[105][106] which the owners anticipated would allow the building to earn a LEED Platinum green building certification.[105][107] The project also involved a more energy-efficient boiler burner and LED lighting.[108] In 2010, the Chicago City Council introduced legislation to permit a $5 million tax credit for the renovation.[106] SOM completed the renovation the same year.[109]

The lobby was temporarily used as a pop-up art gallery in 2012 while the owners looked for a new tenant for the retail space.[110][111] Capital Properties obtained a $50.2 million mortgage loan for the Inland Steel Building in 2013.[112] The same year, Gehry designed a new security desk for the lobby, which was colloquially known as "Icehenge".[113][114] Capital Properties obtained another $60 million mortgage loan from the New York Life Insurance Company in 2016. The owner placed the Inland Steel Building for sale in 2019 for $88 million.[112][115] At the time, 84% of the building's space was occupied by 16 tenants, the largest of which was Oak Street Health with 26,000 square feet (2,400 m2).[112] By 2024, the building's occupancy rate had decreased to 57%[103] or 61%, and the property valuation was less than the amount owed on the loan.[116] As such, New York Life and Blackstone Inc. placed the loan for sale that May.[103][116] New York Life subsequently seized ownership of the building in January 2025.[117][118][119]

Architecture

The Inland Steel Building was designed in a modernist style,[45] particularly the International Style.[120] The design is attributed to Bruce Graham and Walter Netsch of Skidmore, Owings, & Merrill,[121][122] who were longtime rivals.[123] Netsch had drawn up the preliminary design,[121][124] while Graham was the main designer, having taken over after Netsch dropped the commission in favor of designing the Air Force Academy.[121][122] It was SOM's first major structure in downtown Chicago,[125] in addition to being either man's first major Chicago design.[126][127] Gordon Bunshaft, the head of SOM's New York office, advised Graham and Netsch on the design;[122] Metropolis Magazine wrote that the Inland Steel Building's design benefited from Bunshaft's influence.[128] Fazlur Rahman Khan of SOM was responsible for the structural design.[129] After completing the Inland Steel Building, Graham went on to design other skyscrapers in the city, such as the John Hancock Center and the Sears Tower.[95][130]

When the Inland Steel Building was finished, it was described as having included several architectural innovations.[50][131] These included steel pilings, stainless-steel curtain walls, a superstructure without exterior columns, an open plan interior design, and an underground garage.[72][131][132] The building uses 10,000 short tons (8,900 long tons; 9,100 t) of steel,[43] which is used extensively both inside and outside.[133] The use of steel was a reference to Inland Steel's presence,[1] and it also served to promote their products.[45][120][126]

Form and facade

The building's form consists of two distinct masses, namely a 19-story main structure and a 25-story mechanical tower.[10][134][135] Including the mechanical tower, the building measures 332 feet (101 m) tall.[6][136] The mechanical structure—which houses the building's utilities, stairs, and elevators[34][135]—is positioned east of the main structure.[5][6] The idea for the mechanical tower dates from Netsch's original proposal of 1955.[8] Nathaniel A. Owings, one of SOM's cofounders, said the design allowed the building to occupy only 57% of its land lot.[34] while the historian Carl W. Condit said the design split the building into "served" and "servant" spaces, much like Louis Kahn's Richards Medical Research Laboratories.[137] The Inland Steel Building was also one of the first skyscrapers in Chicago to use steel on its facade.[138] Allegheny Ludlum manufactured the building's stainless steel, and Pittsburgh Plate Glass manufactured the glass panes.[139]

Main building

.jpg)

The 1st (ground) and 2nd stories are set back from the rest of the building and have a glass facade.[6][33] On Dearborn Street, these two levels are recessed 10 feet (3.0 m) from the lot line, while on Monroe Street, these levels are recessed 20 feet (6.1 m), creating a ground-level plaza.[25] The recessed lower-story facade allowed the sidewalk outside the building, on both Dearborn and Monroe streets, to be widened.[140] The 3rd through 19th stories extend outward to the lot line, protruding above the first and second stories.[6][140] There is a soffit on the underside of the third floor; the portions of the soffit on the building's northern and southern elevations feature square light boxes.[6] Although the 1st and 2nd stories can be cleaned using standard window washing equipment, the 3rd through 19th stories must be cleaned from a scaffold that is suspended from mechanical arms on the roof.[141] The arms, in turn, run on a narrow-gauge track along the perimeter of the roof.[142]

The curtain wall measures 2 inches (51 mm) thick.[122][135][143] It consists of 1,491 glass panes,[141] which each measure 10 feet (3.0 m) tall[144] and cover about two-thirds of the facade.[135][143] As built, the facade is tinted a deep green[6][125] and is double-layered to help regulate the building's temperature during the winter and summer.[141] Netsch had originally proposed sandwiching the ducts for the building's HVAC system between the two layers of panes, but Graham's final design removed this feature.[122] Unlike in older buildings, where the windows could be opened to take advantage of natural breezes, the Inland Steel Building's windows were sealed shut because the building had an air-conditioning system.[50][141][145] When the building was completed, the curtain wall was about 15 pounds per square foot (73 kg/m2) lighter than older masonry walls,[145] and it weighed 200 short tons (180 long tons; 180 t) less than a similarly-sized wall made of structural steel.[25]

The glass curtain wall is subdivided by a grid of mullions running horizontally and vertically.[6][129] The horizontal mullions are placed 2 feet 4 inches (0.71 m) above the spandrel panels separating each floor.[6] Vertical mullions divide the building into bays measuring 5 feet 2 inches (1.57 m) wide, aligning precisely with the interior floor grid.[59][135][145] The vertical mullions double as guiderails for the window-washing scaffold.[146] Windows on different floors are separated by stainless-steel spandrel panels, with a 2-inch-thick (5.1 cm) layer of either concrete[6][135] or glass behind each panel.[143] The spandrels measure about 10 feet (3.0 m) wide and 2 feet (0.61 m) tall,[6] concealing floor slabs behind them.[145] The mullions and spandrel panels are fastened to the building's steel frame using brackets and bolts.[147] The western and eastern facades each have seven stainless steel columns placed about 25 feet 10 inches (7.87 m), or five bays, apart.[135] Each column measures 4 by 2.5 feet (1.22 by 0.76 m) across[135] and has stone concrete fireproofing.[148] Graham said of the columns' design: "You understand with those columns that it's a clear span, that there are no other columns".[126]

Mechanical tower

.jpg)

The mechanical tower is on Monroe Street and is recessed 25 feet (7.6 m) from the lot line, connected to the southern end of the main building's eastern elevation. A courtyard, also on Monroe Street, separates the main building from the mechanical tower.[6] The facade of the mechanical tower is clad entirely with metal without any window openings.[6][145][149] The metal cladding is attached to precast concrete panels measuring 5 inches (130 mm) thick.[17] Similarly to the main building, it contains vertical mullions placed 5 feet 2 inches (1.57 m) apart.[6]

Structural and mechanical features

In total, the building's frame includes more than 5,000 short tons (4,500 long tons; 4,500 t) of structural steel.[129] The building's foundation consists of 450 steel pilings, which are embedded into the muddy ground below,[52][129] extending to a depth of 85 feet (26 m).[5][24][150] The architects did not extend the pilings down to bedrock, more than 100 feet (30 m) below ground level, as the compacted mud was deemed to be sufficient to support the building's weight.[129] The pilings, the first of their type to be used in a large Chicago skyscraper,[150] support the stainless-steel columns on the western and eastern facades.[151] Because the columns support the entire weight of the building, their existence eliminated the need for interior load-bearing columns or walls.[34][35] SOM called the columns a "modern execution" of early Chicago-style buildings with steel frames.[52] Architectural Forum magazine wrote that the design was descended from early Chicago high-rises such as The Fair Store's flagship building and the Standard Building,[152] while Condit said the exterior columns were similar to those of Mies van der Rohe's S. R. Crown Hall.[137]

The columns on the western and eastern facades are connected by horizontal girders measuring about 60 feet (18 m) long,[59][135][143] twice as long as the 30-foot (9.1 m) girders commonplace at the time.[153] To accommodate these girders, each column has torque box openings, through which the floor beams are inserted.[59][148][153] Unlike older buildings where the steel members were riveted together, the girders and columns were bolted or welded to each other.[50][129] The torque boxes provided stability against wind loads and helped distribute structural loads more evenly throughout the frame.[129] The girders are covered with vermiculite plaster for fireproofing.[148] The floor slabs are cellular galvanized steel decks made by Inland Steel[55][154] and are welded to the building's horizontal floor beams.[59] All mechanical ducts such as communications and electrical wires are embedded into the steel decks,[52][55][153] which are then covered by a concrete slab and a surface finish.[55] This saved space compared to a conventional design, which would have required substantially thicker girders and higher ceilings.[153]

The first two stories, and each group of four or five floors above it, are served by separate mechanical systems.[155] The Inland Steel Building was the Loop's first major commercial building with an air-conditioning system serving the entire structure.[72][112][132] Air is supplied through grilles and diffusers in the ceiling of each story; these are spaced to avoid interfering with the interior floor grid. Each group of floors also has a separate air-outflow system, as well as a chilled water system that provides cool air during the summer.[155] The mechanical tower has two staircases, a freight elevator, and six emergency elevators,[52] in addition to bathrooms and mechanical ducts.[6][52] The two stairs technically violated the city's building code, which required high-rise buildings to have at least two emergency stairs at different locations, but SOM convinced Chicago building officials that the stairs were as far apart as possible.[61] At each floor, a hallway, measuring about 10 feet (3.0 m) long,[35] connects the mechanical tower to the rest of the building.[156] Because the mechanical tower is six stories taller than the rest of the building, the top stories include mechanical rooms.[6][72] Additional mechanical equipment is located in the building's basements.[155]

Interior

Each of the office stories measures 58 by 177 feet (18 by 54 m) across[24][43][143] and is cited as having either 10,000 square feet (930 m2)[35][154] or 10,200 square feet (950 m2) of usable space.[10][21] According to SOM, the mechanical tower freed up a full story's worth of space in the main building, which would have otherwise been used for mechanical purposes.[145] The exterior columns and mechanical tower also completely eliminated the need for interior columns in the main structure.[123][125][157] At the time, Inland Steel executives boasted that the building had the most uninterrupted floor space of any high-rise office building in the world.[132][158] Above the second story, only two of the upper floors—the 13th and 19th stories, which respectively housed a cafeteria and the Inland Steel executive suites—had any spaces with non-movable walls. The remaining stories from the 3rd to the 18th floor, all have the same open plan design.[159] Both the 13th and 19th floors have since been converted into standard offices without any of their original design features.[55] There are also three basements.[6][52]

At the request of Inland Steel CEO Leigh Block, numerous artworks were commissioned for the building.[64][160][161] Sources disagree on whether there were originally 50 paintings and seven sculptures,[161] or just over two dozen total artworks.[162] Richard Lippold and Seymour Lipton were each commissioned to design one large sculpture for the building.[163][164] Harry Bertoia had originally been hired to sculpt a piece for the main lobby, but he was replaced by Lippold.[122] Other artwork was spread across the lobby, offices, and public corridors, and all the pieces signified various aspects of industry.[161] Some of the artwork was still extant in the 1990s,[43] but only one sculpture, Lippold's Radiant I, remained in the building by 2009.[64]

Lower stories

.jpg)

The southern third of the ground (first) floor contains the lobby, which has plate-glass walls on three sides and is accessed through revolving doors to the south. There is a sign with the building's name above the revolving doors. The lobby itself has terrazzo floors and a ceiling with light boxes.[165] In the lobby is Radiant I, which is made of gold, stainless steel, and enameled copper[64][166] and is intended to symbolize Inland Steel.[71] The sculpture is suspended above a reflecting pool,[24][160][167] and a Belgian-marble wall runs behind it.[24][168] The "Icehenge" security desk, designed by Frank Gehry in 2013, weighs 7.5 short tons (6.7 long tons; 6.8 t), with a green-glass surface and a pair of 6-foot-tall (1.8 m) glass columns.[113] The lobby walls were originally clad in black marble, which was partially replaced with Bubinga wood paneling in the 1990s. There is an elevator lobby next to the main lobby, which has six elevators with stainless-steel doors, as well as Bubinga paneling, drywall decorations, and recessed lights. The northern section of the ground floor has retail space, accessed through a revolving door to the west and glass doors on the lobby's northern wall.[165]

The second floor originally had an open plan without interior columns, though it has since been subdivided with glass partitions and non-movable walls. Since the second story's floor slab is set back from the recessed facade, there is a steel handrail surrounding the second story. The second-floor ceiling was built with light boxes, similar to those on the exterior soffit, but this has been covered with a dropped ceiling.[168]

The first basement (just below ground) has a parking garage accessed from Dearborn Street, while the second and third basements below it have mechanical equipment and storage space.[6][52] The first basement is 12 feet (3.7 m) deep and is variously cited as having 60[52][153] or 72 parking spaces.[6] At the time of the building's completion, the garage was one of the first to be integrated into a large Chicago office building.[132] The second basement is 25 feet (7.6 m) deep and the third basement is 34 feet (10 m) deep.[52] The two lower basements include compressors for the building's refrigeration plant, as well as boilers for the heating plans.[153]

Offices

.jpg)

The offices are arranged in a grid of square modules measuring 5 feet 2 inches (1.57 m) on each side.[55][59][143] All private offices measured three modules deep and two to four modules wide,[154][169] while cubicles measured one module deep.[145] For the most part, the offices had movable partitions, which were made by the E. F. Hauserman Company.[154][169][170] The partitions were made of enamel steel and plate glass and were attached to aluminum posts embedded into the floor and ceiling. To give the offices a more open feeling while still providing privacy, the partition walls did not reach the ceiling.[154][171] The partitions were light enough that two workers could handle installation and disassembly,[170] and created what SOM called an "office hotel", as new tenants could simply move the partitions rather than spending large sums of money on interior fit-out.[105][107] Most of the partitions had been removed by the 2000s.[55]

The modular floor plan is mirrored in the design of the ceiling, which contains grooves measuring 2 inches (51 mm) wide; the intersections of these grooves have studs for the partition system's aluminum rods. The grooves divide the ceiling into squares measuring 5 feet (1.5 m) wide.[50][171][a] The offices feature dropped ceilings made by Celotex,[55][154] which are composed of square tiles measuring 1 foot (0.30 m) on each side.[50] The dropped ceilings feature openings for equipment like air diffusers and light boxes, which are aligned with the ceiling grid.[65][171] The steel-and-concrete floor slabs are covered with carpeting or other finishes.[55] The windows had vertical aluminum shutters,[146] as well as fabric louvers that could be tilted 130 degrees.[172]

Inland Steel's offices, which occupied the top eight stories,[21][55] were decorated in a grayscale and brownish palette, with furnishings made of natural materials such as wood and fabric.[172] The offices were furnished with two types of steel-and-teak desks, along with Danish teak chairs, sofas with steel legs, and swivel chairs.[173] Offices on other stories had a palette of primary colors against a gray background, with glass and metal finishes. Tenants' private offices had Steelcase desks with wooden desktops and storage cabinets, along with doors and chairs in shades of blue, yellow, and red.[169][171] The elevator lobby on each floor, within the mechanical tower, has a dropped ceiling and a cellular floor deck, like most of the office space. The walls of the elevator lobbies have mail chutes and, on some stories, have been painted over or covered with wallpaper.[55]

Dining floor and executive suite

The south side of the 13th floor had a kitchen surrounded by multiple executive lounges and private dining spaces, while the north side of that floor contained Inland Steel's lounge and a tenants' dining room.[159][174] The southwest corner of this floor featured the president's dining suite, with a steel-and-walnut table measuring 6 feet (1.8 m) in diameter, along with Danish-teak chairs.[159][175] The various spaces on the 13th floor were delineated by the use of different color schemes for each room.[174] Planting boxes were used to separate the dining areas and the lounges.[174][176] The 13th-story elevator lobby contained Small Tree, a sculpture by Harry Bertoia that consisted of a steel welded frame.[161]

The executive suites on the 19th floor were accessed from a central reception room.[168][172] This space had teak wall panels, charcoal carpets, and teak and steel furniture.[169][172] To the southwest and northwest were the former offices for Inland Steel's president and vice president, respectively.[168] The eastern side of the 19th floor was occupied by a board room with a 27-foot (8.2 m) table, which was so large that it had to be hoisted through the window.[168][177] The board room was the only room without draperies[177] and had sliding glass doors leading to the reception area.[163][178] All of the 19th-floor rooms had custom steel and wood furniture designed by SOM associate Davis Allen.[169] The executive floor contained Lipton's 7-foot-tall (2.1 m) sculpture Hero,[24][133][161] which stood at the end of a corridor.[163] The individual offices had paintings by artists such as Stuart Davis, Willem de Kooning, Arthur Dove, Georgia O'Keeffe, Abraham Rattner, Ben Shahn, and Hedda Sterne.[24][167][179] Inland Steel also displayed winning artworks from art competitions.[167] The company selected a variety of artworks to accommodate executives' differing artistic tastes.[179]

Impact

Reception

.jpg)

During the building's development, the historian Edgar Kaufmann Jr. wrote that the stainless-steel columns enlivened the facade without compromising the building's "unity and dignity", while the mechanical tower's courtyard helped emphasize the main building.[180] When the building was finished, architectural critics generally praised its design as innovative while also relating to Chicago's older architecture.[61] The Chicago Tribune praised the steel columns, saying they were evocative of the "spirit of unity" that Louis Sullivan had achieved with his masonry buildings.[181] Another article for the same newspaper cited it as an "example of progress" in downtown Chicago.[182] Time magazine wrote that it "goes a step or two ahead of almost every other office building in the U.S.",[24] while Architectural Forum called the structure "well-tailored" at a time when most architecture was generic.[28] The Tribune reported in 1960 that it had received numerous letters complaining about the design, although a poll of several dozen tenants found that few were critical of the design.[23]

A writer for the French newspaper Le Monde, reporting on the building in 1965, called it "the most important project erected in the center of Chicago", saying that the open-plan spaces allowed for a myriad of office configurations.[183] The AIA Guide to Chicago summarized the building as having received praise because of its "graceful proportions, the elegance of its detailing, and the sophistication of its public art".[5] In 1977, Paul Goldberger of The New York Times described the building as an "essay in glass and steel", saying that the design was a "deliberate attempt to express the difference between office space (the glass) and mechanical space (the solid)".[149] The critic Paul Gapp called the structure "a gleaming, stainless steel beauty" in 1989, in part because of its mechanical tower.[184] Blair Kamin wrote in 1998 that the Inland Steel Building's exterior "forthrightly expresses itself" despite not being as monolithic as some of Chicago's other Miesian skyscrapers,[185] and The Chronicle of Higher Education referred to the building as a paragon of modernist architecture.[186]

Thomas J. O'Gorman, in a guidebook of Chicago architecture, called the Inland Steel Building "a design triumph whose snazzy pizzazz tantalized Chicago tastes".[125] The National Park Service wrote in 2009 that the building was "an example of SOM's strong stance on the idea of total design", since all aspects of the design had been devised simultaneously, allowing for uninterrupted open-floor plans with modular offices.[50] The Commission on Chicago Landmarks called the building "one of the defining commercial high-rises of the post-World War II era of modern architecture",[1] and Thomas Leslie wrote in 2023 that the building set "a high commercial and architectural bar for projects that followed".[44] Observers also described the building as having a timeless quality[43][187] and being one of Chicago's more prominent post–World War II buildings.[45][188]

Architectural influence and exhibits

When the Inland Steel Building was being designed, it contrasted with older, elaborately decorated buildings in Chicago[112] and was likened to SOM's earlier Lever House in New York.[8][35] It was also cited as having been influenced by the architecture and principles of Mies van der Rohe,[189][190][191] and Graham explicitly stated that he had taken some design elements from Mies's work.[44] The Inland Steel Building, along with Lever House, helped popularize post–World War II modernist architecture in the United States,[192] and Paul Gapp wrote that the design "helped make the city a bastion of Miesianism".[190] In addition, the Inland Steel Building's completion inspired other architects to use stainless steel in their buildings' facades.[193] Richard Tomlinson, a partner at SOM, said in 1991 that many of his clients requested designs that retained their appearance as they aged, much like the Inland Steel Building.[43]

The design has generally not been copied verbatim, but it has influenced other structures.[43] The First Federal Savings and Loan Association annex to the north, constructed soon after the Inland Steel Building's completion, was designed to blend in with the Inland Steel Building.[194] SOM reused elements of the design in other buildings such as One Bush Plaza in San Francisco and Union Carbide Building and One Chase Manhattan Plaza in New York.[191] Chicago buildings such as Holabird & Root's 25 East Pearson Street,[195] VOA Associates's shop for the Chicago Architecture Foundation,[196] and Frank Gehry's 550 West Jackson Boulevard took inspiration from the Inland Steel Building.[197] Gehry said that he had been inspired by the Inland Steel Building as a young architect,[101] and several of Gehry's other designs, such as the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, were influenced by the architect's appreciation of the building's stainless steel.[113][127] Other designs elsewhere were also influenced by the Inland Steel Building's architecture, including Gordon Tait and G. S. Hay's CIS Tower in Manchester,[198][199] and Osborn McCutcheon's Orica House in Melbourne.[200]

During the building's development, SOM displayed drawings of the structure at the Art Institute of Chicago's Burnham Library.[201] In addition, the Art Institute displayed architectural drawings of the Inland Steel Building as part of a 1990 exhibition,[202] and the Harold Washington Library showcased an architectural model of the building in 1993.[203]

Awards and landmark designations

The Inland Steel Building received the Chicago Building Congress's 1958 award for the best new-building design in Chicagoland.[132][204] The American Institute of Architects (AIA) and Chicago Association of Commerce gave the building an award in 1958, proclaiming the Inland Steel Building the city's best new commercial building for that year.[205] The two associations also gave Lippold's sculpture a fine arts award in 1959.[206] The AIA also gave a special 25-year honor award to the Inland Steel Building in 1982, citing the integrity of its design.[207][b] An executive for the Landmarks Preservation Council of Illinois said in 1991 that the building had "long been recognized as a potential landmark" because its exterior frame adhered to the principle that form follows function.[43] The same year, SOM won a design award from the AIA after completing a new cafeteria in the building.[209]

The building was one of the first official landmarks designated in 1958 by the then-new Commission on Chicago Architectural Landmarks,[210] who in 1960 mounted a metallic plaque in front of the building.[211][212] At the time, the building had no legal protections.[157][213] When the city government conducted a survey of Chicago's buildings in 1995, it granted various levels of legal protection, but only to buildings completed before 1940.[213] The Commission on Chicago Architectural Landmarks' successor, the Commission on Chicago Landmarks, designated the Inland Steel Building as a Chicago Landmark on October 7, 1998.[1][4] A square plaque related to the 1998 landmark designation is next to the older commission's metallic plaque.[214] The building was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2009.[215][216] Architectural Record magazine described the Inland Steel Building as one of the United States' "most famous [architectural] works of the mid-20th century" that were protected as local or national landmarks.[217]

See also

References

Notes

- ^ Each 5-foot-2-inch (1.57 m) floor module corresponds to the width of a 5-foot-wide ceiling square and a 2-inch-wide groove.[50]

- ^ Not to be confused with the Twenty-five Year Award, which was awarded to the Commonwealth Building in Portland, Oregon, that year.[208]

Citations

- ^ a b c d "Inland Steel Building". City of Chicago Department of Planning and Development, Landmarks Division. 2003. Retrieved December 16, 2012.

- ^ "Inland Steel Building". Emporis Corporation. Archived from the original on December 9, 2006. Retrieved February 8, 2008.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ a b Chicago Landmarks; Individual Landmarks and Landmark Districts designated as of July 17, 2025 (PDF) (Report). Commission on Chicago Landmarks. July 17, 2025. p. 14. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 17, 2025. Retrieved August 8, 2025.

- ^ a b c d Sinkevitch, Alice; Petersen, Laurie McGovern (2004). AIA Guide to Chicago. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-15-602908-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s National Park Service 2009, p. 5.

- ^ Chu, Jeff (October 14, 2011). "Chicago Architecture Weekend Travel Guide – Take Monday Off". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on February 4, 2023. Retrieved August 14, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e Leslie 2023, p. 91.

- ^ a b c d "Loop Building is Planned by Inland Steel: Needs Lease From School Board". Chicago Daily Tribune. August 20, 1954. p. 43. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved August 7, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, Hitchcock & Danz 1963, p. 75.

- ^ "Zoning Website". City of Chicago. Archived from the original on January 25, 2025. Retrieved January 26, 2025.

- ^ Kamin, Blair (January 8, 2006). "One Fine Box". Chicago Tribune. pp. 7.1, 7.11. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 420443149. Retrieved August 9, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Negronida, Peter (October 10, 1970). "Report Bares School Board Land Income". Chicago Tribune. p. 46. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved August 11, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Washburn, Gary (February 13, 1977). "Eyes turn toward choice chunk of Loop". Chicago Tribune. p. 165. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved August 11, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Inland Steel Plans Loop Skyscraper". The Times. October 14, 1954. p. 1. Retrieved August 7, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d "Razing Starts Soon for New Inland Office". Chicago Daily Tribune. August 12, 1955. p. C7. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 179543357.

- ^ a b c Fuller, Ernest (September 18, 1955). "Inland's New Building Page in Old Story: Points Up Chicago Leadership Role". Chicago Daily Tribune. p. B11. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 179561980.

- ^ a b c d e National Park Service 2009, p. 11.

- ^ a b "Steelmaker Moving". Chicago Daily Tribune. January 10, 1958. p. 49. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved August 8, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Inland Steel, Schools Dicker on Loop Site: Corner of Dearborn, Monroe for Lease". Chicago Daily Tribune. June 10, 1954. p. 28. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved August 7, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d Architectural Forum 1958, p. 90 (PDF p. 96).

- ^ National Park Service 2009, p. 12.

- ^ a b c Schreiber, George (March 14, 1960). "Tenants Like City's Two New Skyscrapers". Chicago Tribune. p. 44. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved August 8, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Art: How to Spell Steel". Time. February 10, 1958. Retrieved August 8, 2025.

- ^ a b c d National Park Service 2009, p. 17.

- ^ a b "Inland Steel Plans $6 Million Office Building in Chicago". The Wall Street Journal. August 20, 1954. p. 5. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 132124632.

- ^ "Inland to Erect Chicago Loop Office Building". The Times. August 19, 1954. p. 2. Retrieved August 7, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Architectural Forum 1958, p. 89 (PDF p. 95).

- ^ "School Board OK's Lease to Inland Steel". Chicago Daily Tribune. October 14, 1954. p. 25. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved August 7, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ McManus, Ed (February 27, 1977). "Chicago's Loop: Who owns it?". Chicago Tribune. p. 1. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 169531165.

- ^ "Inland Steel's Loop Building to Be Started: 19 Story Structure to Cost 6 Million Inland Steel's Loop Building to Be Started". Chicago Daily Tribune. February 28, 1955. p. C5. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 178840989.

- ^ "Inland Steel to Spend Record $40 Million in Capital Outlays in 1955: Projects Include 19-Story Office Building, New Beam Mill, Steep Rock Ore Development". The Wall Street Journal. February 28, 1955. p. 10. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 132217067.

- ^ a b c Fuller, Ernest (November 5, 1955). "Inland Bldg's First, Second Floors Leased". Chicago Daily Tribune. p. 31. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved August 7, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e Fuller, Ernest (March 9, 1955). "New Inland Building to Be of Steel, Glass". Chicago Daily Tribune. p. 51. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved August 7, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f "14 Columns Will Carry New 19-Story Building". The Washington Post and Times Herald. May 22, 1955. p. T9. ISSN 0190-8286. ProQuest 148715514.

- ^ a b Leslie 2023, p. 92.

- ^ Darrow, Joy (December 14, 1967). "Attorney Requests Changes in High Rise Zoning Laws". Chicago Tribune. p. 175. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved August 11, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Kissel, Lee (July 14, 1959). "Chicago Is Getting Well Scrubbed Look". The Daily Chronicle. p. 11. Retrieved August 8, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Loop Sustains Brisk Building Pace Thru Year". Chicago Daily Tribune. January 2, 1957. p. A4. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 180037033.

- ^ a b "Inland Steel Office Building". The Wall Street Journal. August 12, 1955. p. 10. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 132193674.

- ^ a b "1st I Beam for Inland Steel Building". Chicago Daily Tribune. January 10, 1956. p. 55. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved August 8, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ National Park Service 2009, pp. 12–13.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Allen, J Linn (April 3, 1991). "It's Stainless: Inland Steel Building Proves Durable, Aesthetically and Economically". Chicago Tribune. p. G12. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 1644263812.

- ^ a b c Leslie 2023, p. 98.

- ^ a b c d O'Gorman 2003, p. 72.

- ^ "Inland Steel Plans Building". The Chicago Defender. August 20, 1955. p. 28. Retrieved August 7, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Real Estate Notes". Chicago Daily Tribune. November 19, 1955. p. 35. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved August 7, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Turner Gets Inland Contract". The New York Times. November 29, 1955. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 8, 2025.

- ^ "From the Ticker". The Tulsa Tribune. January 10, 1956. p. 32. Retrieved August 8, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j National Park Service 2009, p. 18.

- ^ "Pile Drivers Near End of Task". Chicago Daily Tribune. March 7, 1956. p. C7. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 179769838.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Inland Steel Unit Will Use New Concepts: Completion is Set for Next Fall". Chicago Daily Tribune. November 12, 1956. p. C5. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 179960223. Retrieved August 8, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Inland Steel Lets Contract for New Office Building". The Daily Calumet. June 29, 1956. p. 4. Retrieved August 8, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "1956 Proves Memorable Year for Badger Concrete Company". The Oshkosh Northwestern. December 14, 1956. p. 11. Retrieved August 8, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k National Park Service 2009, p. 7.

- ^ "Real Estate Notes". Chicago Daily Tribune. July 28, 1956. p. 35. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved August 8, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Association of Commerce to Be in Inland Building". The Times. November 11, 1955. p. 11. Retrieved August 7, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Fuller, Ernest (February 9, 1958). "Builders Are Paid a Tribute". Chicago Daily Tribune. p. A9. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 182020051.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Architectural Forum 1958, p. 92 (PDF p. 98).

- ^ "White, Weld Leases Area in New Inland Building". Chicago Daily Tribune. May 30, 1956. p. 55. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved August 8, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e Leslie 2023, p. 97.

- ^ a b c "Inland Unit 98 1/2% Filled". Chicago Daily Tribune. October 10, 1957. p. F8. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 180289440.

- ^ a b c "Inland Building 98 1/2 Per Cent Filled". The Times. October 10, 1957. p. 13. Retrieved August 8, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f National Park Service 2009, p. 20.

- ^ a b c Leslie 2023, p. 96.

- ^ a b Fuller, Ernest (November 2, 1956). "Finish Frame of Inland's Skyscraper: Towers 19 Stories in Loop". Chicago Daily Tribune. p. C7. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 179978573.

- ^ a b "New Inland Structure 'Topped Out'". The Times. November 2, 1956. p. 19. Retrieved August 8, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Worker on Loop Building Loses Life in Accident". Chicago Daily Tribune. June 8, 1957. p. 13. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 180182717.

- ^ "Chicago Worker Killed in Fall". The Times. June 9, 1957. p. 52. Retrieved August 8, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Fuller, Ernest (January 7, 1958). "Look for New Surge in Homebuilding in 1958". Chicago Daily Tribune. p. 36. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved August 8, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, Hitchcock & Danz 1963, p. 79.

- ^ a b c d e "Inland Steel Opens Door of New Building: Loop's First Tall Unit in 20 Years". Chicago Daily Tribune. February 4, 1958. p. B7. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 182088379.

- ^ "Inland Steel's Building Opens". The Belleville News-Democrat. United Press. February 3, 1958. p. 12. Retrieved August 8, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Fire Cracks 9 Windows in Inland Steel Building". Chicago Tribune. February 21, 1958. p. 59. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved August 8, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "$12,000 Damage at Inland Steel Chicago Building". The Times. United Press International. March 9, 1959. p. 16. Retrieved August 8, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "New and Old Materials Give Life to Skyscrapers". Chicago Tribune. February 20, 1966. p. 161. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved August 11, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Houston, Jack (April 30, 1972). "Tours Will Begin Tuesday: Want to Study City's Architecture? You'll Have to Stroll Thru Loop". Chicago Tribune. p. W14. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 170295322.

- ^ Lauerman, Connie (December 8, 1973). "School Board urged to sell $20 million block in Loop". Chicago Tribune. p. S1. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 170996363.

- ^ Sheppard, Nathaniel Jr. (December 4, 1979). "School Board Property May Solve Chicago Fiscal Crisis". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 22, 2020. Retrieved August 11, 2025.

- ^ O'Shea, James (December 23, 1979). "Schools' land holdings may be ace in hole: Schools' land: ace in the hole". Chicago Tribune. p. N1. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 170042223.

- ^ Butwin, David (July 31, 1977). "Chicago No. 1 on architectural parade". The News Tribune. p. 83. Retrieved August 11, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Banas, Casey (August 17, 1981). "Rents total $990,000 a year: Board owns 119 nonschool properties". Chicago Tribune. p. 15. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 172413982.

- ^ "Leasing Agent Named for Inland Building". Chicago Tribune. May 5, 1985. p. 2.D. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 290841038.

- ^ O'Connor, Matt (January 23, 1987). "Inland Steel in Black, Sees More Gains Ahead". Chicago Tribune. p. 3. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 290988098.

- ^ Ziemba, Stanley (August 14, 1988). "Chicago Realty is Picking Up Foreign Accent". Chicago Tribune. p. 1. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 282464322.

- ^ Hornung, Mark (January 4, 1988). "Japanese Money to Play Bigger Role in Real Estate". Crain's Chicago Business. Vol. 11, no. 1. p. 15. ProQuest 198370044.

- ^ Hillkirk, John (August 22, 1988). "Japanese investors hike USA holdings". USA Today. p. 05B. ProQuest 306096044. Retrieved August 11, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Megan, Graydon (December 21, 2014). "John P. Sweeney, Chicago developer, dies". Chicago Tribune. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved August 14, 2025.

- ^ Kerch, Steve (October 29, 1989). "Inland Steel Building rehab part of contract". Chicago Tribune. p. 396. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved August 9, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Richards, Kristen (September 1996). "Architects' offices: Ross Barney and Jankowski, Architects" (PDF). Interiors. Vol. 155, no. 9. pp. 136–139. ProQuest 221570815. Retrieved August 10, 2025.

- ^ a b c "HIK takes space at 30 W. Monroe street". Real Estate Chicago. Vol. 3, no. 3. April 2002. p. 8. ProQuest 216174869.

- ^ Allen, J. Linn (December 30, 1998). "Howard Street Begins to Show Signs of New Life". Chicago Tribune. p. 2. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 418733449.

- ^ "ISPAT Inland renews long-term lease at 30 W. Monroe". Real Estate Chicago. Vol. 2, no. 10. November–December 2001. p. 21. ProQuest 216169499.

- ^ a b "Landmark attracts building designers". Building Design & Construction. Vol. 41, no. 5. May 2000. p. 16. ProQuest 211016167.

- ^ a b "Gehry makes bid to purchase landmark Inland Steel Building". Building Design & Construction. Vol. 46, no. 5. May 2005. p. 7. ProQuest 211054835.

- ^ a b Corfman, Thomas A; Kamin, Blair (April 28, 2005). "Architect Gehry bidder for Inland Steel tower". Chicago Tribune. ISSN 1085-6706. Archived from the original on June 26, 2025. Retrieved August 8, 2025.

- ^ Kamin, Blair (August 20, 2005). "Gehry likes it, helps buy it". Chicago Tribune. p. 2.1. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 420446920. Archived from the original on June 26, 2025. Retrieved August 9, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f Bernstein, Fred A. (November 16, 2010). "Frank Gehry Helps Preserve Inland Steel Building in Chicago". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 4, 2024. Retrieved August 9, 2025.

- ^ Corfman, Thomas A. (July 13, 2005). "Gehry venture to buy Inland Steel building". Chicago Tribune. p. 3.3. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved August 9, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Diesenhouse, Susan (May 11, 2007). "Landmark building sale irks architect". Chicago Tribune. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved August 9, 2025.

- ^ a b c Diesenhouse, Susan (July 14, 2007). "Gehry to aid revamp after Inland Steel Building sale". Chicago Tribune. p. 2.1. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 420550520. Archived from the original on June 25, 2025. Retrieved August 9, 2025.

- ^ "$57 million Inland Steel building deal closes". Chicago Tribune. November 6, 2007. ISSN 1085-6706. Archived from the original on June 25, 2025. Retrieved August 9, 2025.

- ^ a b c Ori, Ryan (May 1, 2024). "Chicago Landmark, Mag Mile Office Tower Become Latest Options for Bargain Shoppers". CoStar. Retrieved August 10, 2025.

- ^ "Owners plans $40-million revamp of Inland Steel Building". Crain's Chicago Business. September 3, 2008. Retrieved August 9, 2025.

- ^ a b c d Seward, Aaron (June 8, 2010). "SOM Goes Retro on Inland Steel". The Architect's Newspaper. Retrieved August 14, 2025.

- ^ a b Kamin, Blair (March 10, 2010). "Inland Steel Building owners may get tax break". Chicago Tribune. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved August 10, 2025.

- ^ a b Chino, Mike (June 21, 2010). "SOM and Frank Gehry Team Up for Inland Steel Eco Renovation". Inhabitat – Green Design, Innovation, Architecture, Green Building. Archived from the original on March 21, 2023. Retrieved August 14, 2025.

- ^ "For Chicago's architectural landmarks, retrofits must balance…". Canary Media. September 16, 2020. Retrieved August 14, 2025.

- ^ "A Year of Ups and Downs". Fast Company. No. 153. March 2011. pp. 18, 20. ProQuest 856210927.

- ^ "Inland Steel building gets Loop Alliance installation". Chicago Tribune. April 4, 2012. p. 4.2. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved August 14, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Hatch, Jared (May 30, 2012). "Sawbridge Studios Opens a Pop Up Called "Idea Tree" in The Loop". Racked Chicago. Archived from the original on May 28, 2024. Retrieved August 14, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e Ecker, Danny (June 24, 2019). "New York investor puts landmark Inland Steel building up for sale". Crain's Chicago Business. Archived from the original on January 22, 2025. Retrieved August 1, 2025.

- ^ a b c Kamin, Blair (July 28, 2013). "Gehry provokes with 'Icehenge'". Chicago Tribune. p. 1.6. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 1412907140. Archived from the original on December 12, 2024. Retrieved August 9, 2025.

- ^ Bentley, Chris (June 19, 2013). "Frank Gehry's Ice Blocks Chilling Out Inside Chicago's Inland Steel Building". The Architect's Newspaper. Archived from the original on April 18, 2024. Retrieved August 9, 2025.

- ^ "Downtown office sell-off continues as investor puts Inland Steel building on the market". The Real Deal. June 24, 2019. Archived from the original on July 8, 2025. Retrieved August 1, 2025.

- ^ a b "Blackstone, New York Life list distressed downtown office buildings". The Real Deal. May 1, 2024. Archived from the original on July 27, 2025. Retrieved August 10, 2025.

- ^ Ecker, Danny (January 21, 2025). "Lender takes over landmark Loop office building". Crain's Chicago Business. Retrieved August 1, 2025.

- ^ Ori, Ryan (January 22, 2025). "Chicago tower, known as first built in Loop after Great Depression, gets handed back to lender". CoStar. Archived from the original on January 23, 2025. Retrieved August 1, 2025.

- ^ Lounsberry, Sam (January 17, 2025). "Lenders plot to refill struggling Chicago office towers after seizing from landlords". The Real Deal. Archived from the original on July 21, 2025. Retrieved August 10, 2025.

- ^ a b Hasted, Keith (August 26, 2019). Modernist Architecture: International Concepts Come to Britain. The Crowood Press. p. 282. ISBN 978-1-78500-620-3.

- ^ a b c Leslie 2023, pp. 91–92.

- ^ a b c d e f Adams, Nicholas (2019). Gordon Bunshaft and SOM: Building Corporate Modernism. Yale University Press. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-300-22747-5.

- ^ a b Kamin, Blair (March 9, 2010). "Bruce Graham dies at 84; architect of iconic Chicago skyscrapers". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 25, 2025. Retrieved August 14, 2025.

- ^ Keegan, Edward (July 6, 2007). "Illinois Pulls Walter Netsch's License Over CEUs". Architect Magazine. Vol. 96, no. 8. p. 26. ProQuest 227831361. Archived from the original on June 16, 2025. Retrieved August 10, 2025.

- ^ a b c d O'Gorman 2003, p. 74.

- ^ a b c Gilfoyle, Timothy J. (Spring 2000). "Creating a Dance: Interviews with Bruce Graham and Maria Tallchief". Chicago History. Vol. 28, no. 3. pp. 54–65. ProQuest 1313462307.

- ^ a b "Architect Walter Netsch dead at 88". Northwest Herald. Associated Press. June 17, 2008. p. 19. Retrieved August 10, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Paletta, Anthony (September 9, 2021). "You Can't Spell SOM Without Gordon Bunshaft". Metropolis. Archived from the original on May 14, 2025. Retrieved August 14, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g Leslie 2023, p. 94.

- ^ Millenson, Michael L. (December 14, 1980). "Architect Graham reshapes city skyline". Chicago Tribune. p. W_C1. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 172220688.

- ^ a b O'Gorman 2003, pp. 74–75.

- ^ a b c d e "Inland Steel Building Cited as 'Dynamic'". The Times. May 11, 1958. p. 17. Retrieved August 8, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Kaufmann 1957, p. 26.

- ^ "Chicago Loop Revitalized Under Vigorous Program". The Indianapolis Star. September 9, 1962. pp. 3.1, 3.3. Retrieved August 11, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Architectural Record 1958, p. 170 (PDF p. 142).

- ^ "Inland Steel Building". Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat – CTBUH. June 25, 2020. Archived from the original on January 13, 2025. Retrieved August 7, 2025.

- ^ a b Condit, Carl W. (January 1, 1964). "The New Architecture of Chicago". Chicago Review. Vol. 17, no. 2. p. 111. ProQuest 1301395752.

- ^ Bilitz, Walter (January 21, 1963). "Glistening Buildings Show Their Metal". Chicago Tribune. p. 47. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved August 8, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Leslie 2023, pp. 94–95.

- ^ a b O'Gorman 2003, p. 75.

- ^ a b c d Fuller, Ernest (July 28, 1957). "Inland Unit Windows Are Nonbudging Kind". Chicago Daily Tribune. p. A9. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 180250531.

- ^ "Oddly Enough, It's a Window Washing Aid". Chicago Daily Tribune. December 21, 1957. p. 25. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved August 8, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f Interiors 1958, p. 112.

- ^ "Art: How to Spell Steel". Time. February 10, 1958. Retrieved August 8, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g Leslie 2023, p. 95.

- ^ a b Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, Hitchcock & Danz 1963, p. 78.

- ^ Architectural Record 1958, p. 174 (PDF p. 146).

- ^ a b c Architectural Record 1958, p. 173 (PDF p. 145).

- ^ a b Goldberger, Paul (September 25, 1977). "A Critic's Guide to Chicago's Loop, The Birthplace of the Skyscraper". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 16, 2024. Retrieved August 7, 2025.

- ^ a b O'Gorman 2003, pp. 72, 74.

- ^ "Inland Steel Foundation Work to Begin: Drive Supporting Piles Tomorrow Inland Steel Foundation to Be Started". Chicago Daily Tribune. January 9, 1956. p. C5. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 179709872.

- ^ Architectural Forum 1958, pp. 89–90 (PDF pp. 95–96).

- ^ a b c d e f Leslie 2023, p. 93.

- ^ a b c d e f "'Totally useful' building" (PDF). Industrial Design. Vol. 5, no. 5. May 1958. p. 88.

- ^ a b c Architectural Record 1958, p. 178 (PDF p. 150).

- ^ Fuller, Ernest (March 9, 1955). "New Inland Building to Be of Steel, Glass". Chicago Daily Tribune. p. 51. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved August 7, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Sharoff, Robert (August 19, 1996). "Famous – yes; landmarks – no: Some choice buildings lack formal distinction". Crain's Chicago Business. Vol. 19, no. 34. p. SR1. ProQuest 198453679.

- ^ "Inland Steel Co. Plans Expansion: Will Double Its Flange Beam Capacity and Abandon Rail Production Shortage is Cited". The New York Times. September 6, 1957. p. 37. ISSN 0362-4331. ProQuest 114195512.

- ^ a b c National Park Service 2009, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b Interiors 1958, p. 113.

- ^ a b c d e Sullivan, Marin R. (2022). Alloys: American Sculpture and Architecture at Midcentury. Princeton University Press. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-691-23246-1.

- ^ Kaufmann 1957, pp. 22–23.

- ^ a b c Architectural Forum 1958, p. 91 (PDF p. 97).

- ^ Kaufmann 1957, p. 22.

- ^ a b National Park Service 2009, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Marter, Joan M. (2011). The Grove Encyclopedia of American Art. Oxford University Press. pp. 172–173. ISBN 978-0-19-533579-8.

- ^ a b c Millard, Nancy (July 9, 1978). "Modern Sculptures Highlight Windy City Walking Tour". The Star Press. p. 11. Retrieved August 11, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e National Park Service 2009, p. 6.

- ^ a b c d e National Park Service 2009, p. 19.

- ^ a b Leslie 2023, pp. 95–96.

- ^ a b c d Interiors 1958, p. 119.

- ^ a b c d Interiors 1958, p. 114.

- ^ Interiors 1958, p. 117.

- ^ a b c Interiors 1958, p. 121.

- ^ Interiors 1958, p. 120.

- ^ Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, Hitchcock & Danz 1963, p. 81.

- ^ a b Interiors 1958, p. 115.

- ^ Architectural Record 1958, p. 177 (PDF p. 149).

- ^ a b Kaufmann 1957, p. 27.

- ^ Kaufmann 1957, p. 25.

- ^ "Beauty in Steel". Chicago Daily Tribune. February 5, 1958. p. 16. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 182101506.

- ^ Gavin, James M. (January 4, 1960). "Billions to Be Invested Downtown". Chicago Daily Tribune. p. D10. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 182421623.

- ^ Michel, Jacques (September 2, 1965). "Architecture Et Architectes Américains: II. – L'homme Qui Donna Leur Nouveau Visage Aux Etats-Unis" [American Architecture and Architects: II. – The Man Who Gave the United States Their New Face]. Le Monde (in French). p. 8. ProQuest 2502495660.

- ^ Gapp, Paul (May 7, 1989). "An architectural tour of the Windy City". The Kansas City Star. pp. 1.I, 3.I. Retrieved August 9, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Kamin, Blair (February 6, 1998). "Masters of Understatement". Chicago Tribune. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved August 11, 2025.

- ^ Biemiller, Lawrence (February 23, 1996). "Lessons in wood and stone". The Chronicle of Higher Education. Vol. 42, no. 24. p. C5. ProQuest 214726508.

- ^ Curtis, Wayne (October 6, 2002). "Admiring Mies and Modernism, Up Close". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 25, 2024. Retrieved August 9, 2025.

- ^ Schulze, Franz; Harrington, Kevin (2003). Chicago's Famous Buildings (5th ed.). University of Chicago Press. p. 75. ISBN 0-226-74066-8..

- ^ "Windy City is Up, Up and Away..." The Dispatch. Copley News Service. September 1, 1969. p. 16. Retrieved August 11, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Gapp, Paul (September 6, 1981). "Architecture: Skidmore & Co.: A Design Giant Reshapes Chicago". Chicago Tribune. p. E14. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 172438180.

- ^ a b Sennott, R. Stephen (2004). Encyclopedia of Twentieth Century Architecture. Taylor & Francis US. p. 1212. ISBN 978-1-57958-435-1.

- ^ Cramer, Ned (March 2004). "The Bauhaus Effect". Interior Design. Vol. 75, no. 3. p. 178. ProQuest 234948863.

- ^ Kamin, Blair (March 4, 1998). "As 2 New Projects Demonstrate, Protecting Postwar-era Classics Needs to Be a Priority". Chicago Tribune. p. 1. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 418581207.

- ^ "First Federal's New Addition". Chicago Daily Tribune. August 5, 1958. p. 45. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved August 8, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Kamin, Blair (September 25, 1994). "Loyola Tower Fails to Soar; a New Academic Building Downtown Stands Aloof From the City but Shows Results of Smart Planning Inside". Chicago Tribune. pp. 13.7, 13.34. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 283904911. Retrieved August 11, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Mosher, Diana (June 2002). "Tour de force". Contract. Vol. 44, no. 6. pp. 106–108. ProQuest 223763928.

- ^ Kamin, Blair (November 18, 2001). "Building on past in West Loop". Chicago Tribune. p. 108. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved August 9, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Sale of an icon: Why the Co-operative Insurance Tower is so significant". Co-operative News. May 25, 2017. Retrieved August 7, 2025.

- ^ Macdonald, Susan; Normandin, Kyle C.; Kindred, Bob (December 8, 2015). Conservation of Modern Architecture. Routledge. p. 40. ISBN 978-1-317-70489-8.

- ^ Haigh, Gideon (September 7, 2016). "Melbourne's bold leap upwards: the inside story of Australia's first skyscraper". The Guardian. Archived from the original on October 8, 2016. Retrieved August 14, 2025.

- ^ "Architects' Display Sets Precedent". Chicago Daily Tribune. January 14, 1957. p. 70. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved August 8, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Gapp, Paul (August 5, 1990). "Scraping the sky Drawing on Chicago architects and 23 skidoo!". Chicago Tribune. p. 18. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 282987760.

- ^ Kamin, Blair (May 16, 1993). "City on the plain A new exhibit on the irresistible rise of Chicago". Chicago Tribune. p. 26. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 283509631.

- ^ "Building Achievement Award". Chicago Tribune. May 10, 1958. p. 9. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved August 8, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Fuller, Ernest (April 11, 1958). "Hails Signs of July End to Slump: Szymczak Talks at Award Fete". Chicago Daily Tribune. pp. C7. C9. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 182101963. Retrieved August 8, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Fuller, Ernest (April 15, 1959). "New Buildings Cited as Proof of City Spirit: 11 Get Awards; Urban Renewal Hailed". Chicago Daily Tribune. p. B11. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 182291683. Retrieved August 8, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Gapp, Paul (September 17, 1982). "Design awards given to city's best". Chicago Tribune. p. 44. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved August 11, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Twenty-five Year Award Recipients". American Institute of Architects. Archived from the original on June 15, 2012. Retrieved April 4, 2024.

- ^ Gapp, Paul (June 9, 1991). "Building on details Award-winning designs take tailor-made approach". Chicago Tribune. p. 3. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 283092308.

- ^ "Architectural Honors Given 9 'Landmarks'". Chicago Tribune. June 26, 1958. p. 30. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved August 8, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "38 Structures to Be Honored as Landmarks: Plaques to Be Given Owners at Fete". Chicago Daily Tribune. February 7, 1960. p. 21. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 182457224.

- ^ "Inland Steel Company Building Historical Marker". hmdb.org. Retrieved January 27, 2025.

- ^ a b Demirjian, Karoun (November 2, 2007). "Not-so-old tower named a landmark". Chicago Tribune. p. 2C.11. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 420627914. Retrieved August 11, 2025.

- ^ "Inland Steel Building Historical Marker". hmdb.org. Retrieved January 27, 2025.

- ^ Hinderer, Katie (October 19, 2009). "Inland Steel Building To Get Boutique Upgrade". GlobeSt. Retrieved July 18, 2025.

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places Adds Trio of Local Sites". The Chicagoist. March 9, 2009. Archived from the original on November 15, 2017. Retrieved July 18, 2025.

- ^ Longstreth, Richard (September 2000). "What to save? Midcentury Modernism at risk" (PDF). Architectural Record. Vol. 188, no. 9. pp. 59–61. ProQuest 222157088.

Sources

- Historic Structures Report: Inland Steel Building (PDF) (Report). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. February 18, 2009.

- "Inland's steel showcase" (PDF). Architectural Forum. Vol. 97, no. 4. April 1958.

- "Inland Steel" (PDF). Architectural Record. Vol. 123, no. 4. April 1958.

- Kaufmann, Edgar (Winter 1957). "The Inland Steel Building and Its Art". Art in America. Vol. 45, no. 4. ProQuest 1299881375.

- Leslie, Thomas (2023). Chicago Skyscrapers, 1934–1986: How Technology, Politics, Finance, and Race Reshaped the City. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-05411-2.

- "Offices" (PDF). Interiors. Vol. 118, no. 3. October 1958. pp. 112–121.

- O'Gorman, Thomas J. (2003). Chicago. Architecture in detail. PRC. ISBN 978-1-85648-668-2.

- Skidmore, Owings & Merrill; Hitchcock, Henry-Russell; Danz, Ernst-Joachim (1963). Architecture of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, 1950–1962. Frederick A. Praeger. OCLC 1333097.