In Toga Candida

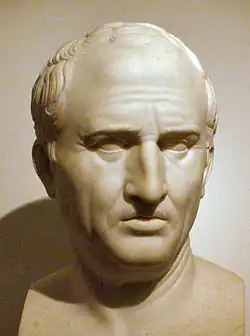

In Toga Candida was a speech given by the Roman orator Marcus Tullius Cicero in 64 BC, shortly before the election of the consuls for 63 BC. Cicero was standing in that election and used the speech to attack two rival candidates, Lucius Sergius Catilina (known in English as Catiline) and Gaius Antonius Hybrida.

The full text of the speech has been lost, but over a thousand words of it have been preserved in quotation by Asconius, who wrote a detailed commentary on the speech about a century after it was given, which has survived.[1]

Name

The conventional Latin title of the speech is Oratio in Toga Candida, lit. 'speech in a whitened garment'. The toga was a cloth robe worn by male Roman citizens on formal occasions. It was typically made of undyed wool, though magistrates were identified by a Tyrrhenian purple stripe on their toga. While a politician was actively campaigning for an election, it was traditional for their toga to be made a more brilliant white (candidus), by bleaching the wool then rubbing it with chalk. The resulting garment was known as the toga candida; this is the origin of the English word 'candidate'.[2] Therefore the title of the speech can also be translated as 'speech as a candidate'[3] or 'speech while dressed for an election'.

Political context

The politics of the Roman Republic was dominated by aristocratic families. The electoral system for the most powerful magistrates (by the centuriate assembly) favoured richer voters, who tended to support candidates from a family of nobiles – those with ancestors who had previously held the office of consul (head of state). In contrast, Cicero was a novus homo lit. 'new man', the first of his family to be elected to public office. He had risen through the series of increasingly powerful offices that formed the cursus honorum and was now standing for the position of consul.

Two consuls were elected each summer for a one-year term that began in the following January. In the early Republic the position had been monopolised by the patricians, but over the centuries laws had been put in place to limit their dominance. By the late Republic, only one of the consuls each year could be a patrician; one or two of those elected had to be plebeian.

For the consular elections of 64 BC, there were an unusually large number of candidates, with seven men standing for the two positions. Two were patricians: Catiline and Publius Sulpicius Galba. Five were plebeians: Gaius Antonius Hybrida, Cicero, Lucius Cassius Longinus, Quintus Cornificius and Gaius Licinius Sacerdos. Catiline, Galba, Hybrida and Longinus were all nobiles. In an attempt to secure their joint election, Catiline and Hybrida had formed an alliance (akin to a modern joint ticket) and were engaging in electoral bribery, backed by funds from Marcus Licinius Crassus and facilitated by Gaius Julius Caesar.

Concerned by the increasing use of bribery, the Roman Senate proposed stricter rules against it (the existing law was the Lex Acilia Calpurnia). The Senate, however, was not a legislative body, so its proposed law had to be voted on by the tribal assembly. When that assembly was held, the law was vetoed by Quintus Mucius Orestinus, one of the tribunes of the plebs, preventing it from being passed. As an explanation of his veto, Orestinus made a speech declaring that Cicero was unworthy to become consul.[4] Cicero had previously defended Orestinus in a legal case, securing his acquittal, so felt that Orestinus was obliged to support him and that his behaviour was a breach of their patron-client relationship.

The Senate debated the issue again on the day after the bill was vetoed when Cicero was called upon to speak.[4] He had prepared a speech to attack the characters of Catiline and Hybrida and the veto applied by Orestinus.[4] He avoided directly naming Crassus and Caesar, but alluded to their roles as key supporters and enablers of the bribery.

Contents

In the speech, Cicero accused Catiline and Hybrida as having met with a 'prominent citizen' (probably Crassus or Caesar) to organise bribery.[5] He calls Catiline a murderer for the latter's role in Sulla's proscriptions, particularly his execution of Marcus Marius Gratidianus and parading of Gratidianus' severed head through the city.[5] He points out that Catiline openly admitted his actions during the proscriptions, while similar actions by other supporters of Sulla had resulted in criminal convictions.[5]

Cicero also decries Catiline's rapacious governorship of Africa, pointing out that Catiline had withdrawn from a previous consular election because he was being prosecuted for extortion in Africa.[5] That case ended in Catiline being acquitted, but Cicero obliquely criticises the judge and prosecutor in the case (the latter was Catiline's friend Publius Clodius Pulcher) without naming them.[5]

Catiline is also attacked as an adulterer and for his impious prosecution of a Vestal virgin (Fabia, the sister of Cicero's wife Terentia).[5] Cicero alleges that Catiline conspired with Gnaeus Piso to murder members of the Senate, and began a separate conspiracy with a gladiator named Licinius.[5][6]

Although most of the speech is directed at Catiline, Cicero also directly attacks Hybrida and Orestinus. Like Catiline, Hybrida is criticised for his role in Sulla's regime and proscriptions.[5] Cicero describes Hybrida as a robber, as acting like a gladiator, and as having appeared as a driver in Sulla's chariot races. Gladiator and chariot driver were both considered dishonourable occupations; they were performed by slaves not Roman citizens, and certainly not senators.[5]

He argues that Orestinus was confident in Cicero's abilities when appointing him as a defence lawyer, yet now asks the Roman people not to place confidence in Cicero as consul.[5] Orestinus is accused of obstructing both the existing bribery law and the Senate's proposal to strengthen it.[5]

Aftermath

Cicero's speech was successful in persuading the conservative senators to support his candidacy over that of Catiline. With the senators came the support of their clients. In the election held a few days later, Cicero won with unanimous support from all the centuries that were called to vote[7] (voting was always halted once the outcome became inevitable). Hybrida secured the second consulship, while Catiline came third so was not elected.

The tactics were successful and he secured the consulship.[8][9]

Cicero and Hybrida reconciled before their terms as consul began, because Cicero offered Hybrida the potentially lucrative proconsulship of the province of Macedonia (which would begin at the end of their term).

Conversely, Catiline was incensed, both by the electoral rejection and Cicero's tactics of invective personal attacks. This was Catiline's second unsuccessful attempt to secure the consulship and he was left almost bankrupt by the campaign, especially the bribes. He resolved to seize power by force and began recruiting other discontented politicians to organise a coup. The resulting Catilinarian conspiracy planned to kill Cicero and Hybrida, then take control of the government using an armed force. Responding to the conspiracy would dominate Cicero's consulship, during which he delivered several further speeches attacking Catiline, known as the Catilinarian orations. Cataline fled to his rebel army and was killed in battle, while Cicero executed several of Catiline's supporters without a trial - an action which would haunt his subsequent career and lead to Cicero's exile by Clodius.

Textual transmission

A commentary on the speech was written by Asconius between 54 and 57 AD.[3] Asconius provides background on each of the candidates in the election, then quotes numerous passages of Cicero's speech, interspersing them with his own historical comments and observations.[3]

References

- ^ Petersson, Torstein (1920). Cicero: A Biography. Out of Copyright reprint Kessinger Publishing, LLC. ISBN 978-1417951864.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ "Candidate". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2012-11-07.

- ^ a b c M. G. L. Cooley, ed. (2023). "Asconius' commentary on Cicero's speech as a candidate". Cicero's Consulship Campaign (second ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 29. doi:10.1017/9781009383547.005.

- ^ a b c Jane W. Crawford; Andrew R. Dyck, eds. (2024). "In Toga Candida". Cicero, Fragmentary Speeches. Loeb Classical Library. Vol. 556. Harvard University Press. p. 178.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "The Fragments of the Speech of Cicero in His White Gown (In Toga Candida), against C. Antonius and L. Catilina, His Competitors for the Consulship. Delivered in the Senate". Translated by Barbara Saylor Rodgers. 2009. Retrieved 3 July 2025.

- ^ Shotter, David Colin Arthur (2005). The Fall Of The Roman Republic (Second ed.). New York, N.Y.: Routledge. p. 55. ISBN 0-415-31940-4.

In two places — in his own election speech (Oratio in Toga Candida) in 64 and in his Orations against Catiline in the following year — Cicero alleged that on 1 January 65, Catiline was in the Forum with a dagger ready to assassinate the incoming consuls...

- ^ Lintott, Andrew (February 2008). "Candidature and Consulship". Cicero as Evidence: A Historian's Companion. Oxford University Press. p. 129. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199216444.003.0010. ISBN 9780199216444.

Cicero was elected consul by the unanimous vote of all the centuries required to give him the necessary majority

- ^ H.H. Scullard From the Gracchi to Nero: A History of Rome 133 BC to AD 68 2010 p92 "In a speech to the Senate (Oratio in Toga Candida: candidates wore specially whitened togas) Cicero denounced his rivals and hinted that there were secret powers behind Catilinia. Thus Cicero, the novus homo, secured the consulship for 63"

- ^ Erich S. Gruen The Last Generation of the Roman Republic 1974 270 "Catilinia's early career gained impetus from nimble maneuvering and resourceful and unscrupulous tactics. Tradition registers a catalogue of perversities, several drawn from Cicero's venomous In Toga Candida and the Commentariolum Petitionis: adulterous activities, incest, sacrilege, and domestic homicide."