Hoplophoneus

| Hoplophoneus | |

|---|---|

| |

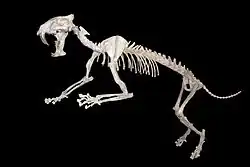

| H. primaevus skeleton, Zurich natural history museum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Family: | †Nimravidae |

| Subfamily: | †Hoplophoninae |

| Genus: | † Cope, 1874 |

| Type species | |

| Hoplophoneus primaevus Leidy, 1851

| |

| Other Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

H. occidentalis

H. primaevus

| |

Hoplophoneus (Greek: "murder" (phonos), "weapon" (hoplo)[1]) is an extinct genus of the family Nimravidae, lived in North America and Asia during the Late Eocene to Early Oligocene epochs from 35.7 to 30.5 mya, existing for approximately 5.2 million years.[2][3]

Taxonomy

H. strigidens was considered nomen dubium by Bryant in 1996.[4] In 2000, an unnamed species of Hoplophoneus within Late Eocene rocks was found in Thailand.[5]

In 2016, all North American species of Eusmilus were placed in Hoplophoneus by Paul Z. Barrett.[6] However, in 2021, Barret revised this phylogeny. His phylogenetic analysis suggests H. cerebralis, H. dakotensis, and H. sicarius were actually species of Eusmilus instead of Hoplophoneus.[3]

Description

Hoplophoneus, though not a true felid, was similar to cats in outward appearance. Hoplophoneus showed adaptations of high specialization, such as the development of its canines and mandibular flange and overall robustness of its build. The humerus of Hoplophoneus showed prominent areas for insertion of deltoid and supinatory muscles, resembling that of later barbourofelids and thylacosmilids.[7] H. primaevus is estimated to have weighed 15–19.5 kg (33–43 lb) and stood 48 cm (1 ft 7 in) at the shoulders.[8][9][7] H. occidentalis was significantly larger than H. primaevus. While Sorkin, in his 2008 study, estimated that the largest individual have weighed 160 kg (350 lb), similar to a large jaguar.[10] Other experts suggested a smaller size. Turner suggested H. occidentalis was about the size of a large leopard.[11] Based on a sample size of 8 specimens, Meachen found that the species weighed 65 kg (140 lb).[9] This species was found to have been sexually dimorphic.[12]

Paleobiology

Brain anatomy

The posterior vermis of the cerebellum was found to be straight, although the overlap of the cerebellum by the cerebrum was smaller than extant felids. It was also found that the olfactory bulbs were relatively small in Hoplophoneus.[13] Despite this, H. primaevus was found to similar encephalization quotient to cougars, and scoring higher than jaguars.[14]

Predatory behavior

Due to the presence of robust bones and large areas of muscle attachments, Meachen speculated that H. occidentalis showed specialization for large prey.[9] Lautenschlager et al. 2020 estimated the jaw gape for this species to be around 98.22°. In addition, H. oharri and H. primaveus had a jaw gape of 97° and 95° respectively. They argue due to the wide jaw gape of over 90°, combined with little bending strength values over time suggests they have an intermediate killing strategy towards large prey.[15] Including supplementary materials

However, Anderson et al. 2011 found that increased jaw gape and canine size has a great impact on small to medium sized prey, but little impact on large prey. Based on their analysis, they argue the adaptation of sabertoothed predators was killing normal sized prey faster than their nonsabertooth counterparts.[16] Elbow morphology recovered Hoplophoneus as an ambush predator.[17]

Pathology

An adult specimen of H. primaevus discovered in Badlands National Park, South Dakota, in 2010 by paleontologist Clint Boyd et al. was found to have bite marks on its skull from the teeth of another adult individual of Hoplophoneus. From examination of the wounds, it was found that the animal had been wounded by its rival's saber-teeth. Regrowth of bone around the injuries shows that the nimravid survived the attack. Similar finds also reveal that such fights were likely commonplace among nimravids and that they would often aim for the back of the skulls and eyes of their opponents.[18]

Paleoecology

H. occidentalis roamed North America from the Late Eocene to Early Oligocene from 33.4 to 31.4 mya.[3] Including supplementary materials This species was found in the Brule Formation of South Dakota. It coexisted with predators such as the contemporary species H. primaevus, entelodontidae Archaeotherium mortoni, hyaenodontinae Hyaenodon and contemporary herbivores such the extinct camel Poebrotherium wilsoni, and extinct rhino Subhyracodon.[19]

H. primaevus was the dominant cat-like predator, with its only serious competitor being the larger hyaenodonts like Hyaenodon.[20]

References

- ^ "Glossary. American Museum of Natural History". Archived from the original on 20 November 2021.

- ^ Turner, Alan. National Geographic Prehistoric Mammals. National Geographic, 2004., pp.120-121

- ^ a b c Barrett, Paul Zachary (26 October 2021). "The largest hoplophonine and a complex new hypothesis of nimravid evolution". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 21078. Bibcode:2021NatSR..1121078B. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-00521-1. PMC 8548586. PMID 34702935. S2CID 240000358.

- ^ Prothero, DR; Emry, RJ; Bryant, HN (1996). "Nimravidae". The Terrestrial Eocene-Oligocene Transition in North America. pp. 453–475.

- ^ Peigné, Stéphane; Chaimanee, Yaowalak; Jacques, J. J; Suteethorn, Varavudh; Ducrocq, Stéphane (March 2000). "New Eocene nimravid carnivoran from Thailand". Journal of Verterbrate Paleontology. 20 (1): 157–163.

- ^ Barrett PZ. (2016) Taxonomic and systematic revisions to the North American Nimravidae (Mammalia, Carnivora) PeerJ 4:e1658 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.1658

- ^ a b Turner, Alan (1997). The Big Cats and their Fossil Relatives: an illustrated guide. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-231-10228-5.

- ^ Dubied, Morgane; Solé, Floréal; Mennecart, Bastien (29 July 2019). "The cranium of Proviverra typica (Mammalia, Hyaenodonta) and its impact on hyaenodont phylogeny and endocranial evolution". Paleontology. 62 (6): 983–1001. doi:10.1111/pala.12437.

- ^ a b c Meachen, J. A. (2012). "Morphological convergence of the prey-killing arsenal of sabertooth predators". Paleobiology. 38 (1). doi:10.2307/41432156.

- ^ Sorkin, B. (2008-04-10). "A biomechanical constraint on body mass in terrestrial mammalian predators". Lethaia. 41 (4): 333–347. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.2007.00091.x.

- ^ Turner, Alan (1997). The Big Cats and their Fossil Relatives: an illustrated guide. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 234. ISBN 978-0-231-10228-5.

- ^ Turner, Alan (1997). The Big Cats and their Fossil Relatives: an illustrated guide. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-231-10228-5.

- ^ Lyras, George A.; Geer der van, Alexandra Anna; Werdelin, Lars (November 2022). "Paleoneurology of Carnivora". Paleoneurology of Amniotes, New Directions in the Study of Fossil Endocasts. pp. 681–710. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-13983-3_17.

- ^ Dubied, Morgane; Solé, Floréal; Mennecart, Bastien (29 July 2019). "The cranium of Proviverra typica (Mammalia, Hyaenodonta) and its impact on hyaenodont phylogeny and endocranial evolution". Paleontology. 62 (6): 983–1001. doi:10.1111/pala.12437.

- ^ Lautenschlager, Stephan; Figueirido, Borja; Cashmore, Daniel D.; Bendel, Eva-Maria; Stubbs, Thomas L. (2020). "Morphological convergence obscures functional diversity in sabre-toothed carnivores". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 287 (1935): 1–10. doi:10.1098/rspb.2020.1818. ISSN 1471-2954. PMC 7542828. PMID 32993469.

- ^ Andersson, K.; Norman, D.; Werdelin, L. (2011). "Sabretoothed carnivores and the killing of large prey". PLOS ONE. 6 (10): e24971. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...624971A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0024971. PMC 3198467. PMID 22039403.

- ^ Castellanos, Miguel (2024). Hunting Types in North American Eocene and Oligocene Carnivores and Implications for Nimravid Extinction (Graduate Research Thesis & Disserations)

- ^ The Dakota Badlands Used to Host Sabertoothed Pseudo-Cat Battles

- ^ PaleoBiology Database: Brule Formation

- ^ Antón, Mauricio (2013). Sabertooth. Bloomington, Indiana: University of Indiana Press. p. 48. ISBN 9780253010421.

.jpg)