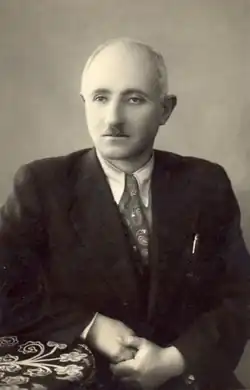

Hasan Urangi

Hasan Urangi | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1910 Tabriz, East Azerbaijan Province, Iran |

| Occupation(s) | politician, public figure |

| In office 12 december 1945 – 12 december 1946 | |

Hasan Urangi or Hasan Orangi (born 1910, date of death unknown) was a politician who served as Minister of Health in the Azerbaijan People's Government.

Following the collapse of the Azerbaijan People's Government, Urangi was arrested. No reliable information is available regarding his subsequent life.

Biography

Hasan Urangi was born in 1910 in Tabriz.[1] In May 1945, he was among the members of a delegation from Southern Azerbaijan invited to Baku to mark the 25th anniversary of the establishment of Soviet power in Azerbaijan[2][3][4]

On November 20, 1945, the Azerbaijan People's Congress began its work at the Ark Theatre in Tabriz.[5][6][7] Urangi participated in the Congress as a delegate.[8] Following the establishment of the National Government of Azerbaijan on 12 December 1945,[9] he was appointed Minister of Health in the newly formed government.[10][11][12][13][14]

During Urangi’s tenure as Minister of Health, 35 hospitals, polyclinics, and outpatient clinics were constructed, and 38 medical stations were established in villages. The number of hospital beds increased to 800, while the number of doctors rose to 200.[15] A medical faculty and a three-year medical technical school were opened at Tabriz University to train nurses.[16] In addition, 5–6 month training courses were launched to prepare mid-level medical staff, and by the time the National Government collapsed, 120 medical workers had completed these courses.[15] While the Iranian government had allocated 32,000 tomans for healthcare in Azerbaijan in 1945, more than 5 million tomans were allocated during the period of the National Government of Azerbaijan.[15]

On 5 December 1946, Shah’s troops advancing toward Miyaneh were halted by fedai forces under the command of Ghulam Yahya.[17][18] In response, residents from various regions of Azerbaijan appealed to the National Government for arms to resist the Shah’s forces.[19] Subsequently, under the leadership of Mir Jafar Pishevari, a Defense Committee was established.[20][21] Its first actions were to declare martial law in Tabriz and to form volunteer units known as Babak.[19][22][23] In the initial phase, these units numbered about 600 members.[21][24] Pishevari again appealed to the Soviet Union for military assistance,[19][25] but the request went unanswered.[26]

On 11 December 1946, the Azerbaijan Provincial Assembly, in an effort to prevent bloodshed, resolved that the Qizilbash People’s Army and fedai forces should not resist the Shah’s troops and should withdraw from the battlefields.[27][28][29]From that day forward, before the Iranian army entered major cities, armed bands led by landlords and plainclothes gendarmes began committing massacres in those areas.[30][31] Tehran Radio referred to these groups as “Iranian patriots.”[31] Their primary objective was to eliminate the Democrats and facilitate the entry of the Shah’s forces into the cities.[30][31]

Tabriz and other Azerbaijani cities were subjected to widespread looting and massacres.[30][32] The National Government of Azerbaijan collapsed.[33] [34] OOn 14 December 1946, the Iranian army, supported by the United States and Great Britain, entered Tabriz.[35][36] Looting and massacres continued thereafter.[32][35] Thousands of people were arrested and exiled.[37] Among those killed during the massacres were members of the Azerbaijan Democratic Party, fedais, and notable poets such as Ali Fitrat, Sadi Yuzbendi, Jafar Kashif, and Mohammadbaghir Niknam.[38][39][40] Urangi was arrested by the Shah's forces on 16 January 1947.[41] No information is available regarding his subsequent life.

References

- ^ Atabaki 2000, p. 124.

- ^ Vəkilov 1991, p. 62.

- ^ Ağayeva 2004, p. 21.

- ^ Həsənli 1998, p. 163.

- ^ Atabaki 2000, p. 113.

- ^ Həsənli 1998, p. 269.

- ^ Həsənov 2004, p. 132.

- ^ "Təbrizdə keçirilmiş Xalq Konqresinə seçilmiş nümayəndələrin siyahısı". azerbaycan-ruznamesi.org. Archived from the original on 2022-11-30. Retrieved 2025-02-27.

- ^ İbrahimov 1948, p. 32.

- ^ Atabaki 2000, p. 130.

- ^ Ağayeva 2004, p. 27.

- ^ Çeşmazər 1986, p. 65.

- ^ "تاریخ شفاهی :: فرقة دموکرات آذربایجان از زبان ابراهیم ناصحی". www.oral-history.ir. Retrieved 2025-02-14.

- ^ Образование национального правительства Иранского Азербайджана (PDF) (in Russian). Vol. 6625. Tbilisi: Заря Востока. 1945-12-18. p. 4.

- ^ a b c Həsənov 2004, p. 174.

- ^ Behzadi 2004, p. 16.

- ^ Rəhmanifər, Məhəmməd (2015-01-04). "Güney Azərbaycanda Milli Hökumətin süqutundan sonra nələr yaşandı?". Apa.az (in Azerbaijani). Archived from the original on 2025-01-04. Retrieved 2025-02-06.

- ^ Həsənli 2006, p. 437.

- ^ a b c Həsənli 2006, p. 438.

- ^ Rəhimli, Əkrəm (2010). Güney Azərbaycan: tarixi, siyasi və kulturoloji müstəvidə. / S.C.Pişəvəri gənclik illərində (PDF) (in Azerbaijani). Bakı: Azərnəşr. p. 83. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-07-08. Retrieved 2025-02-06.

- ^ a b Hasanli 2006, p. 366.

- ^ Atabaki 2000, p. 172.

- ^ Sultanlı 2010, p. 83.

- ^ Rəhimli 2003, p. 143.

- ^ Rəhimli, Əkrəm (2016). Pişəvəri S.C. Məqalə və çıxışlarından seçmələr (Təbriz 1945-1946-cı illər) (in Azerbaijani). Bakı: Nurlar nəşriyyatı. p. 415.

- ^ Həsənli 2006, p. 441.

- ^ Rossow 1956, p. 30.

- ^ Rəhimli 2003, p. 149.

- ^ Hasanli 2006, p. 370.

- ^ a b c Hasanli 2006, p. 373.

- ^ a b c Balayev 2018, p. 36.

- ^ a b Duqlas, Vilyam (1951). Strange lands and friendly people. Nyu-York: Harper & Brothers Publishers. p. 45.

- ^ Lenczowski, George (1972). United States' Support for Iran's Independence and Integrity, 1945–1959. Vol. 401. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. p. 49. doi:10.1177/000271627240100106. ISSN 0002-7162.

- ^ Həsənli 2006, p. 445.

- ^ a b Həsənli 2006, p. 448.

- ^ McEvoy, Joanne; O'Leary, Brendan (2013). Power Sharing in Deeply Divided Places. Filadelfiya: University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 191. ISBN 9780812245011.

- ^ Hasanli 2006, p. 375.

- ^ Balayev 2018, p. 137.

- ^ Əmirov 2000, p. 51.

- ^ Əliqızı 2001, p. 24.

- ^ Mərəndli 2017, p. 155.

Literature

- Atabaki, Touraj (2000). Azerbaijan: Ethnicity and the Struggle for Power in Iran. London: I.B.Tauris. p. 288. ISBN 9781860645549.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Ağayeva, Gözəl (2004). Təbriz ədəbi mühiti (in Azerbaijani). Bakı: Nurlar NPM. p. 168. ISBN 9952403356.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Balayev, Xaqan (2018). Azərbaycanın sosial-siyasi həyatında cənublu mühacirlərin iştirakı (1947-1991) (in Azerbaijani). Bakı: Elm və təhsil nəşriyyatı. p. 198. ISBN 9789952370911.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Behzadi, Behzad (2004). Demokratik Azərbaycan - Azərbaycanda 1324-1325-ci illərdə baş vermiş hadisələrə baxış (in Persian). Tehran: Düzgün xəbər nəşriyyatı. p. 48.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Çeşmazər, Mirqasım (1986). Azərbaycan Demokrat Partiyasının yaranması və fəaliyyəti (PDF) (in Azerbaijani). Bakı: Elm nəşriyyatı. p. 121. Archived from the original on 2023-05-02. Retrieved 2024-11-29.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Əliqızı, Almaz (2001). Azadlıq və istiqlal poeziyası (PDF) (in Azerbaijani). Bakı: Bakı Dövlət Universiteti nəşriyyatı. p. 160. ISBN 9789952817607. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2025-01-28. Retrieved 2025-03-14.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Əmirov, Sabir (2000). Azərbaycan milli-demokratik ədəbiyyatı (1941-1990) (in Azerbaijani). Bakı: Elm (nəşriyyat, SSRİ). p. 257. ISBN 5806612600.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Hasanli, Jamil (2006). At the Dawn of the Cold War: The Soviet-American Crisis over Iranian Azerbaijan, 1941–1946 (in Azerbaijani). Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 416. ISBN 978-0742540552.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Həsənli, Cəmil (1998). Azərbaycan:Tehran - Bakı - Moskva arasında (PDF) (in Azerbaijani). Bakı: Diplomat nəşriyyatı. p. 324. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2024-12-04. Retrieved 2024-11-28.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Həsənli, Cəmil (2006). СССР-Иран: Азербайджанский кризис и начало холодной войны: 1941-1946 гг (PDF) (in Russian). Moskva: Герои Отечества. p. 560. ISBN 5910170120. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2024-12-21. Retrieved 2024-12-25.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Həsənov, Həsən (2004). Azərbaycanda Milli Demokratik hərəkat (1941-1946-cı illər) (in Azerbaijani). Bakı: Elm nəşriyyatı. p. 204.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - İbrahimov, Mirzə (1948). O демократическом движении в Южном Азербайджане (in Russian). Bakı: Elm nəşriyyatı. p. 48.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Mərəndli, Barış (2017). "21 Azər" soyqırımı: 1946-1947-ci illərdə Azərbaycanda kütləvi qırğınlar (in Azerbaijani). Bakı: Elm və təhsil nəşriyyatı. p. 376. ISBN 9789952831283. Archived from the original on 2024-12-07. Retrieved 2024-12-03.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Rəhimli, Əkrəm (2003). Milli-demokratik hərəkat (1941-1946) (in Azerbaijani). Bakı: Meqa nəşriyyatı. p. 207. Archived from the original on 2024-12-17. Retrieved 2024-12-26.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Rossow, Robert (1956). "The Battle of Azerbaijan, 1946". Middle East Journal. X (1): 17–32. JSTOR 4322770. Archived from the original on 4 February 2022.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Sultanlı, Vaqif (2010). Azərbaycan tarixi siyasi və kulturoloji müstəvidə (məqalələr toplusu) (in Azerbaijani). Bakı: Azərnəşr. p. 172.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Vəkilov, Cavanşir (1991). Azərbaycan Respublikası və İran: 40-cı illər (in Azerbaijani). Bakı: Elm nəşriyyatı. p. 136. ISBN 5806604969.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link)