Hans Amlie

Hans Amlie | |

|---|---|

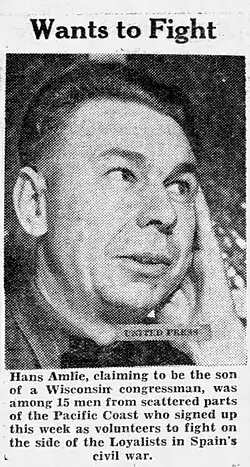

Amlie in 1937 | |

| Born | September 5, 1900 Cooperstown, North Dakota, U.S. |

| Died | December 14, 1949 (aged 49) Somerton, Arizona, U.S. |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch | |

| Years of service | 1917–1919 1919–1921 1937 |

| Rank | Corporal Private Battalion Commander |

| Unit | The "Abraham Lincoln" XV International Brigade |

| Commands | Lincoln Battalion |

| Battles / wars | |

| Resting place | Golden Gate National Cemetery |

| Alma mater | Montana State School of Mines |

| Political party | Socialist (before 1937) Communist (after 1937) |

| Spouse(s) |

Margaret

(m. 1920; div. 1939) |

| Relatives | Thomas Ryum Amlie (brother) |

Hansford "Hans" Amlie (September 5, 1900 – December 14, 1949) was an American mining engineer, political activist and soldier who served in the United States Army and Marine Corps during and after World War I and in the International Brigades during the Spanish Civil War. In the latter conflict, he rose from commanding the 25-man "Debs Column" to the 500-man Lincoln Battalion.

Early life

Hansford Amlie was born on September 5, 1900 in Cooperstown, North Dakota.[1] His family was of Norwegian descent.[2][3] He was active in radical politics as young as 14 years old, when he joined the Industrial Workers of the World[4] following the Ludlow Massacre.[5] He attended Cooperstown High School and was on the debate team with his brother, future congressman Thomas Ryum Amlie.[6]

Following American entry into World War I, Amlie enlisted in the Army at the age of 16,[7] serving in France as a Corporal.[8][9] After the war's end, he re-enlisted in the Marine Corps in 1919,[10] serving as a private until 1921.[1][11] Some sources also give his rank as sergeant.[5][12] During his second tour, he married a woman named Margaret with whom he separated in 1936.[13]

After leaving the military, Amlie attended the Montana State School of Mines and became a mining engineer. Turning away from the declining IWW, he joined the United Mine Workers of America and supported Progressive Senator Robert M. La Follette in the 1924 presidential election.[4]

During the Great Depression, Amlie moved to California[4] and was involved in the labor movement there, taking part in the 1934 West Coast waterfront strike.[14] By 1937, he was living in San Francisco and working as an orderly at the French Hospital.[15]

Spanish Civil War

Following the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, the Socialist Party of New York put out a call for 500 men to form a "Eugene V. Debs Column" to join the pro-Republican International Brigades.[16][17] Amlie, having been a member of the Socialist Party since he cast his first vote for Debs in 1920,[18] answered the call and was chosen to lead the column.[1] However, the officially pacifist national party was noncommital in its support for the column,[16] and in the end only 25 men could be mustered. Amlie, disgusted by the party's actions, resigned to join the Communist Party.[19]

Amlie arrived in Spain on March 17, 1937, joining the XV International Brigade's predominantly-American George Washington Battalion. He attended officer training school and was given command of the battalion's 1st Company ahead of the Battle of Brunete.[1] Assigned to him as political commissar was civil rights lawyer Bernard Ades.[20] During the advance on Villanueva de la Cañada, Amlie tried to lead his men out of a sniper's line of fire and was shot in the hip.[21] As he later recalled:

I had gone only a few steps when I saw the head and shoulders of the foe lift. I knew that I'd made a blunder and started dropping. A bullet caught me low in the side and plowed through to the backbone. It felt as if I had been cut through the back with a hot cleaver. I remembered letting loose a long groan and thinking, "I've been killed," but I recovered my senses almost immediately. I had fallen in a small irrigation ditch a few inches deep. I was paralyzed from the waist down, but my arms were all right and my head was clear.[22]

Amlie was eventually pulled to safety and hospitalized at the Ritz Hotel in Madrid. Upon his recovery, he was promoted to battalion commander of the reorganized Lincoln-Washington Battalion[21] (now numbering less than 500 men after heavy losses),[23] with Belfast-born[24] International Seamen's Union organizer John Quigley Robinson assigned to him as battalion commissar.[20] Deeply caring for the wellbeing of his men,[19] one of Amlie's first acts as commander was ensuring those with poor eyesight had spare glasses in case theirs were broken in combat.[21]

Amlie first led the battalion into combat at Quinto, where they were called on to reinforce the Dimitrov Battalion in a three-day battle that resulted in a Republican victory.[25] Notably, the Americans led the assault, and did so with artillery, armored, and close air support, the first time they were afforded such luxuries.[20] The town would subsequently serve as brigade headquarters for the next several months.[26]

Amlie’s second and last battle as battalion commander would be at Belchite. After taking up positions in shallow trenches outside the town, he and his men came under heavy sniper fire. Unable to effectively take cover or retreat without being picked off, they were forced to attack. Without the support they’d had at Quinto, they quickly sustained heavy casualties; in one assault, 22 men were sent forward, of which 20 were killed and the remaining two could not make it.[19] When brigade chief of staff Robert Hale Merriman came on the radio to order another attack, Amlie flat out refused, and was backed up by his commissar, Robinson.[23] One of his subordinates, Wilbur Wellman (also from San Francisco),[27] described the situation as follows:

...Amlie would not tell the men to continue the advance. When Amlie got the orders: "Either send your men and see that they go, or you face court-martial!" Amlie said to us: "What'll I do? Court-martial at the front means shot!" And we said, "Well, you just give us the order. You order us to go and then we'll refuse. Then you tell them to come down here and lead us, and we'll follow them!"[23]

The situation was resolved when brigade commissar Steve Nelson came to the frontline himself and discovered a culvert than ran directly into Belchite, sparing Amlie and his men from another frontal assault. Though the Republicans were ultimately victorious, Amlie was again wounded, this time shot in the head. While the wound wasn't fatal, it was bad enough that he could not continue fighting and therefore had to be replaced as battalion commander.[19]

Later life and death

While recovering in a field hospital, Amlie met Milly Bennett, an American journalist sent by the Associated Press to cover the civil war. While in country, she had learned that an old boyfriend, Wallace Burton, was serving in the Lincoln Brigade, but by the time she reached the front he had been killed.[3] She sought out Amlie, his commanding officer, to find out how he had died, and after getting to know each other Amlie and Bennett fell in love with each other.[28] They were married on December 1[29] in a "deathbed marriage;" neither of them had the birth certificates required for a regular marriage, so a friendly doctor was convinced to provide paperwork that Amlie was on his deathbed.[3] The couple returned to the United States on January 1, 1938.[28]

Upon his return, Amlie has his passport confiscated by the U.S. government for his involvement in the war.[11] He then embarked on a continentwide[30] speaking tour to raise funds and awareness for the Lincoln Brigade and the war in Spain.[28] Even his brother Thomas, who had voted the previous year to ban the exportation of weapons to either side in Spain,[31] raised money to bring wounded Americans home.[12]

In December 1938, Amlie and Bennett moved to Mill Valley, California.[32] By 1940, Amlie was working as a migrant camp superintendent for the California State Relief Administration.[33] He was later hired by the Farm Security Administration[34] and War Food Administration[28] to manage similar camps across the Western United States.[11] During and after World War II, he and his wife were investigated by the Federal Bureau of Investigation for alleged Communist activity, although little evidence was found and Amlie was allowed to continue working for the government.[28]

Amlie died at a migrant camp in Somerton, Arizona on December 14, 1949.[35] He had gone down into a cesspool to fix a clog in the septic tank,[21] and as he was climbing back up he asphyxiated on the fumes and collapsed.[35] Two migrant workers attempted to rescue him but died as well.[36]

Works

- "At the Battle of Brunete". Blue Book. Vol. 68, no. 3. January 1939. pp. 135–136.

References

- ^ a b c d "Amlie, Hans". alba-valb.org. Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives. December 9, 2019. Retrieved July 23, 2025.

- ^ "Thomas Ryum Amlie Papers, 1888-1967". digicoll.library.wisc.edu. Wisconsin Historical Society. Retrieved July 24, 2025.

- ^ a b c Hochschild, Adam (2016). Spain in Our Hearts: Americans in the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939. London: Macmillan Publishers. pp. 242, 245–246. ISBN 978-1-5098-1059-8. Retrieved July 26, 2025.

- ^ a b c Marion, G. (July 19, 1937). "David White, Hans Amlie; Two Yank Fighters in Spain". Daily Worker. New York. Retrieved July 23, 2025.

- ^ a b Payne, Robert (1963). The Civil War In Spain, 1936-1939. London: Secker & Warburg. p. 168. Retrieved July 23, 2025.

- ^ "Won Third Debate". The Wahpeton Times. Wahpeton. April 20, 1916. Retrieved July 23, 2025.

- ^ "Marine Corps Week opens in United States". The Fargo Forum and Daily Republican. Fargo. June 11, 1917. Retrieved July 23, 2025.

- ^ "Once N. D. Man Fights In Spain". The Fargo Forum. Fargo. July 25, 1937. Retrieved July 23, 2025.

- ^ Fisher, Harry (1997). Comrades: Tales of a Brigadista in the Spanish Civil War. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. p. 23. Retrieved July 24, 2025.

- ^ "Local Army Enlistments". Deseret News. Salt Lake City. November 18, 1919. Retrieved July 23, 2025.

- ^ a b c Bennett, Milly (1993). On Her Own: Journalistic Adventures from San Francisco to the Chinese Revolution, 1917-1927. Armonk: M. E. Sharpe. p. xiii. Retrieved July 24, 2025.

- ^ a b Rosenstone, Robert A. (1969). Crusade of the Left: the Lincoln Battalion in the Spanish Civil War. New York: Pegasus Books. pp. 161, 339. Retrieved July 24, 2025.

- ^ "Hans Amlie Faces Suit for Divorce". International News Service. March 15, 2025. Retrieved August 9, 2025.

- ^ "Hans Amlie Injured Fighting With Spanish Loyalist Army". The Capital Times. Madison. July 15, 1937. Retrieved July 23, 2025.

- ^ "S. F. Recruiting Speed". San Francisco Examiner. San Francisco. January 8, 1937. Retrieved July 23, 2025.

- ^ a b Chatfield, Charles (1971). For Peace and Justice: Pacificism in America, 1914-1941. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. pp. 242–243. ISBN 978-0-87049-126-9. Retrieved July 24, 2025.

- ^ Brooks, Chris (February 14, 2017). "Lorenz Kaufman and the Eugene Victor Debs Column". albavolunteer.org. The Volunteer. Retrieved July 24, 2025.

- ^ "Recall Amlie As Bold Youth". The Fargo Forum. Fargo. December 12, 1937. Retrieved July 24, 2025.

- ^ a b c d Carroll, Peter N. (1994). The Odyssey of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade: Americans in the Spanish Civil War. Stanford: Stanford University Press. pp. 72–73, 155–157. Retrieved July 24, 2025.

- ^ a b c Landis, Arthur H. (1968). The Abraham Lincoln Brigade. New York: The Citadel Press. pp. 172–173, 261–280. Retrieved July 24, 2025.

- ^ a b c d Eby, Cecil (1969). Between the Bullet and the Lie: American Volunteers in the Spanish Civil War. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. pp. 147–150, 166. ISBN 978-0-03-076410-3. Retrieved July 24, 2025.

- ^ Amlie, Hans (January 1939). "At the Battle of Brunete". Blue Book. Vol. 68, no. 3. pp. 135–136.

- ^ a b c Landis, Arthur H. (1989). Death in the Olive Groves: American Volunteers in the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939. New York: Paragon House. pp. 66, 78–81. ISBN 978-1-55778-051-5. Retrieved July 26, 2025.

- ^ "Robinson, John Quigley". alba-valb.org. December 11, 2019. Retrieved July 26, 2025.

- ^ "La Batalla de Quinto (24-26 agosto 1937)". griegc.com. GRIEGC. Retrieved July 27, 2025.

- ^ "Historia". quinto.es. Quinto City Council. September 14, 2014. Retrieved July 27, 2025.

- ^ "Wellman, Wilbur Ed". alba-valb.org. Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives. December 11, 2019. Retrieved July 28, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e Kirschenbaum, Lisa A. (2015). International Communism and the Spanish Civil War; Solidarity and Suspicion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 179, 187, 192–193, 217–218. Retrieved August 7, 2025.

- ^ "Amlies Brother Weds in Spain; War Romance". Associated Press. December 9, 1937. Retrieved August 7, 2025.

- ^ "Memorial Meet Takes Place At Massey Hall". Daily Clarion. Toronto. February 26, 1938. Retrieved August 9, 2025.

- ^ "ILLEGAL TO EXPORT FIREARMS TO SPAIN". voteview.com. University of California Los Angeles. Retrieved July 23, 2025.

- ^ "Woman International Correspondent Finds Peace Beneath Redwoods Here". Mill Valley Record. Mill Valley. December 23, 1938. Retrieved August 9, 2025.

- ^ Bennett, Milly (October 9, 1940). "SRA Crew Provides Blood For Foreman". The Press Democrat. Santa Rosa. Retrieved August 9, 2025.

- ^ "Fourth Migratory Camp For Arizona Is Ready". Tucson Citizen. Tucson. September 10, 1941. Retrieved August 9, 2025.

- ^ a b "SEVEN DIE IN GAS ACCIDENTS". The Arizona Republic. Phoenix. December 15, 1949. Retrieved August 13, 2025.

- ^ "Leaking Septic Fumes Are Fatal to 3 People". Associated Press. December 14, 1949. Retrieved August 13, 2025.

External links

Media related to Hans Amlie at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Hans Amlie at Wikimedia Commons- Hansford “Hans” Amlie at Find a Grave

- Pictures at ancestry.com