Grotte de Cotencher

Cave entrance. | |

| Location | Switzerland |

|---|---|

| Region | Rochefort, Neuchâtel |

| Coordinates | 46°57′51″N 6°48′08″E / 46.964167°N 6.802222°E |

| Altitude | 660 m (2,165 ft) |

| Area | 200 m2 |

| History | |

| Periods | Middle Paleolithic |

| Site notes | |

| Website | https://maisonnaturene.ch/grotte-de-cotencher/ |

The Grotte de Cotencher is a cave in the Jura Mountains located in the Canton of Neuchâtel, Switzerland. It is a high-altitude Mousterian site, the first of its kind discovered in Switzerland in 1867, and it has served as a reference for research on the fauna contemporary with the Mousterian since the first major excavations (1916-1918). The cave is primarily known for yielding a large number of lithic artifacts (approximately 450), as well as Neanderthal human remains.

Following recent work, the cave was reopened to the public in 2018 and is accessible from June to September as part of guided tours led by an expert guide.[1] As for the finds from the site, some are exhibited at the Laténium in the section titled "Au pays du Grand Ours," along with a cross-section taken from the site showing its stratigraphy. Meanwhile, bone remains uncovered during the initial excavations in 1867, including canines and paws of Ursus spelaeus,[2] can be viewed at the Musée de l'Areuse, located in Boudry, Neuchâtel.[3]

Location and geological context

The Grotte de Cotencher opens onto the territory of the commune of Rochefort. It is located at the outlet of the Val-de-Travers, on the northern slope of the Areuse Gorge, which flows 130 metres (430 ft) below. Its altitude is 660 metres (2,170 ft).[4]

The cave is situated on the eastern flank of an anticline; the dip of the stratigraphic layers at the cave level is estimated at 15 to 20 degrees to the east. It is located within layers of yellow-spotted limestone from the Malm superior; a few dozen meters to the south, one transitions to a Nerinid bed overlying massive limestone layers from the Kimmeridgian.[5]

Characteristics

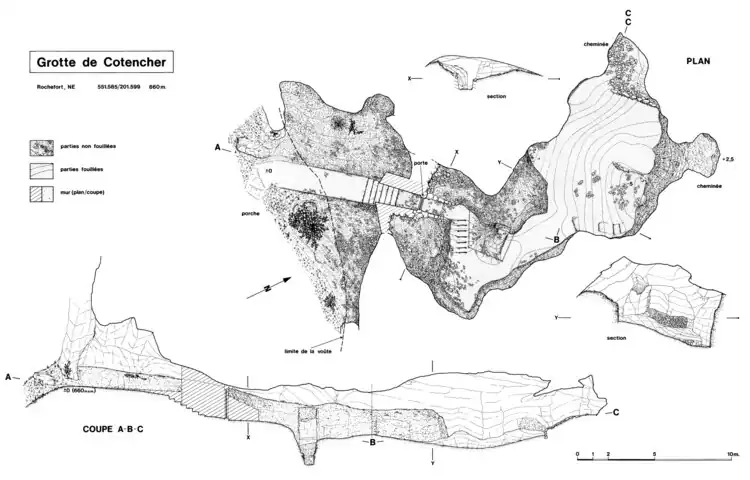

The length of the cave is 18 metres (59 ft), with a surface area of approximately 200 square metres (2,200 sq ft).[6] Its maximum height is 5 metres (16 ft). Additionally, its rounded appearance raises the hypothesis that it was a phreatic cavity carved by water infiltration into the rock; however, it is possible that ceiling gelifraction altered its appearance,[7] as it acts as a true cold air trap in winter.[7]

Before archaeological excavations, it was almost entirely filled with sediments: only a narrow access under the porch allowed entry by crawling. These sediments are of significant scientific interest, as they were protected from glacial erosion that destroyed the region's soils and their archaeological content during the Last Glacial Maximum. They can thus provide substantial information about the environment surrounding the cave during interglacial stages,[8] and the cave's stratigraphy also serves as a mineralogical reference for the Jurassic Pleistocene and its surroundings.[9]

History

Site discovery

The Grotte de Cotencher (or sometimes "Cottencher") is mentioned as early as 1523,[6] but it was during construction work on the "Franco-Swiss" railway along the Val-de-Travers in the second half of the 19th century, that it was discovered. The two researchers Henri-Louis Otz and Charles Knab conducted the first excavations of the cave in 1867, creating two trenches where they identified, among other things, bones of cave bears,[4] which they considered at the time to be an accumulation of human origin.[9] The cave's significance was quickly recognized, as Edouard Desor made it a model type of cave in his 1872 article Essai de classification des cavernes du Jura.[1]

First major excavations

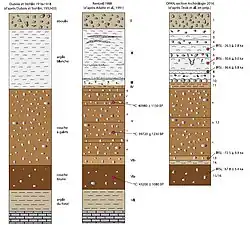

The first major archaeological excavations were carried out from 1916 to 1918 by geologist Auguste Dubois and paleontologist Hans Georg Stehlin. During these campaigns, these scholars identified the first traces of human activity in the cave.[8] They provided an initial reading of the sediment stratigraphy, identifying the following layers (from youngest to oldest): "debris" containing archaeological remains from the Holocene; "white clays"; "pebble layers"; "brown layer"; basal clay. They noted that the "brown layer" and especially the "pebble layer" were very rich in paleontological and archaeological material. In the former, they found, among other things, burnt and calcined bear bones near large stones covered with a charcoal coating.[4] In the latter, they uncovered thousands of bones belonging to about sixty animal species and over 400 Mousterian lithic artifacts, attesting to the presence of Neanderthals during the formation of these layers.[8]

Lithic remains

Of the 600 m3 of sedimentary content in the cave, they excavated 300 m3, uncovering a total of 416 lithic remains, which represent the vast majority of the material found at the site since its discovery. These remains are primarily flakes and flake fragments, but also some cores, mostly of the discoid type, and laminar products. Moreover, their homogeneity suggests a single occupation of the site or multiple occupations closely spaced in time.[4] These remains have confirmed the use of a non-Levallois debitage for the majority,[4] although evidence of Levallois and Kombewa debitage has also been observed.[4] A significant portion of the lithic assemblage consists of scrapers, reflecting a Mousterian dominated by scrapers, with discoid debitage and tools reminiscent of eastern Quina-type discoveries.[4] The materials themselves are mostly local, as most were sourced within a radius of less than 5 kilometers,[4] and are primarily composed of Valanginian flint.[4]

Neanderthal remains

One of the major discoveries at the site was made by Dr. H.-F. Moll during a simple visit to the cave in 1964; he excavated an upper maxilla of a Neanderthal from the "brown layer," which, according to an anthropological study conducted in 1981 by Roland Bay, belonged to a female individual around forty years old.[9] This study linked this individual to Neanderthal types found in the Hortus cave (Hérault, France), suggesting possible contacts between the populations of the Swiss Jura and the French Rhone region. This upper maxilla is the most significant Neanderthal remain known in Switzerland to date.[10]

Stratigraphy reassessment

New excavations, resulting from a collaboration between the Neuchâtel Cantonal Archaeology Service and the Institute of Prehistory at the University of Basel,[7] took place in 1988, with the primary goal of refining the site's stratigraphy. Thus, P. Rentzel and his collaborators identified seven sediment layers, notably (from youngest to oldest): cryoclastic deposits from the Holocene (Layer I); two fine-textured post-glacial layers (II and III); an interpleniglacial pebble layer (V); a layer of reworked sediments from the Eemian (VI).[4]

| Layer | Description according to Deák et al. (2019)[8] | Description according to Rentzel (1990)[4] | Description according to Dubois and Stehlin (1932-1933)[4] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Angular and more or less flattened limestone fragments (2–14 cm in diameter) in a humic granular silt matrix | I: Several cryoclastic levels dating from Protohistory and the Middle Ages | Debris containing archaeological remains from the Holocene |

| 2 | Highly porous white granular silt with ordinary angular limestone fragments (5–12 cm in diameter) in its upper part and some small limestone fragments (2–3 cm in diameter) in its lower part | II: Yellow silts | Sterile white clay |

| 3 | Homogeneous gray clayey-sandy silt | ||

| 4 | Slightly brownish clayey-sandy silt with ordinary angular rock fragments (3–5 cm in diameter) | ||

| 5 | Light gray/white slightly clayey sandy silt. IRSL dating: 26.5 ± 2.8 ka | ||

| 6 | Old gravel level: 0.5–11 cm deep, angular or sub-rounded limestone gravel | ||

| 7 | Homogeneous light gray silty to clayey-silty sediments. IRSL dating: 30.6 ± 3.0 ka | ||

| 8 | Fine white bleached sand, well-sorted. IRSL dating: 36.6 ± 3.8 ka | ||

| 9 | Gray-brownish clayey sediment | III: Silty-clayey sediments | |

| 10 | Angular limestone rocks (10–20 cm in diameter) and rounded/sub-rounded limestone gravel | ||

| 11 | Heterometric, rather compact sediment, composed of limestone and a crystalline rock fragment in a fine, slightly humic, gray-brownish silty material | IV: Succession of gravels with a sandy-silty matrix | |

| 12 | Gravelly layer containing angular, sub-rounded, and rounded gravel in a humic sandy-silty fine material | V: Deposits with limestone elements and pebbles in a sandy-silty matrix | "Pebble layer" |

| 13 | Light brown sandy to clayey-silty silt with small gravel (±3mm in diameter). IRSL dating: 72.5 ± 9.4 ka | VIb: Alternation of silty beds and sandy lenses | |

| 14 | Fine, well-sorted, stratified, yellowish-greenish sand deposit, present as irregular patches at the top of layer 15 or incorporated into its upper part | ||

| 15/16 | Orange sandy silt with some rather weathered limestone rock fragments (5–8 cm in diameter). IRSL dating: 67.8 ± 3.4 ka | VIa: Reddish sandy matrix | "Brown layer" |

| VII: Deep karst deposit under a coarse limestone encrusted elemental deposit | Basal clay |

In addition to the first topography of the site,[7], three carbon-14 datings were established from charcoal samples from the "brown layer" and the "pebble layer." The results indicate that the archaeological remains are at least 40,000 years (1,300,000 Ms) old.[9] These sedimentological and mineralogical analyses reinforce the cave's status as a reference stratigraphy for the Jurassic Pleistocene and its surroundings.[7] Syntheses by Jean-Marie Le Tensorer and Sébastien Bernard-Guelle suggest that the site primarily served as a temporary refuge, consistent with the possibility of a seasonally mobile Jura population.[9]

Faunal remains

Found mainly in the "brown layer" and the "pebble layer," faunal remains largely consist of bones of Ursus spelaeus. However, they include other extinct species such as the lion and the Woolly rhinoceros in layer V. They also include species still present in the region, such as the wildcat, lynx, wolf, and red fox in layer V, as well as the marten, stoat, polecat, weasel, horse, red deer, ibex, chamois, wild boar, mountain hare, marmot, vole, hamster, several amphibians, fish, and birds, as well as bats in layer VI. Similarly, species that have left the region were found, such as the panther, dhole, Arctic fox, and reindeer in layer V, as well as the wolverine and collared lemming in layer VI. It is difficult to determine the extent of human involvement in this bone assemblage, except for two bones bearing traces of manipulation.[4]

While some specialists, given the presence of different species by layer, have suggested an interstade with glacial fauna but sheltered by a temperate biotope containing mainly trees and shrubs for layer V, layer VI would reflect a slightly colder period where herbaceous plants thrived.[4] This hypothesis is debated, however, as the site underwent successive sedimentological reworking, such as that accompanying the retreat of the Würm glacier during the Lower Pleniglacial.[4]

Recent excavations

In 2016, new excavations were initiated under the "Projet Cotencher" set up by the archaeology section of the Neuchâtel Office of Heritage and Archaeology (OPAN) in partnership with the Association de la Maison de la Nature Neuchâteloise. The aim of this interdisciplinary project was to raise awareness and educate the public about natural and archaeological heritage. The Cotencher site benefited from the replacement of its old facilities to, on one hand, protect the archaeological substance and, on the other, make cave visits possible again.[7] The project also considers the conservation of cave fauna,[7] particularly regarding bats, two of the seven species observed at the site being endangered either in Switzerland or on a larger scale: the barbastelle and the greater horseshoe bat.[7]

Innovations in excavation techniques

New techniques not previously used at the site were applied, leading to the discovery of a new corpus of knapped stone objects, as well as bone remains, some of which were found in the "white clay layer" previously characterized as sterile. The use of the IRSL dating method revealed dates much older than those previously established, estimating Neanderthal occupation at least 70,000 years (2,200,000 Ms) before present.[9] Discoveries of manufacturing waste and a new scraper in flint[9] also highlight the exploitation of available materials and biotopes around the cave. Human activities primarily took place under the cave's porch.[11]

The new methods also include topography, photogrammetry, and 3D modeling. Thus, approximately 14 m2 of surface were documented, three 3D models of two test pits, and eight stratigraphic sections by controlled stripping were produced.[7] Additionally, a 3D topography of the cave by the Swiss Institute of Speleology and Karstology (ISSKA) reflects the cave's appearance before the September 2017 works,[7] and a digital twin of the entire cavity obtained by Laserscan through the work of the Archéo développement company[7] is available online.[12]

Sedimentological chronology

The new analyses notably enabled the establishment of a more precise chronology, highlighting numerous climatic events (from most recent to oldest):[7]

- a period of climatic warming after the Last Glacial Maximum (layers 2 to 4);

- during the Last Glacial Maximum, around (+/-) 26,000 BP and 36,000 BP, a glacier would have blocked the cave's entrance for some time (layers 5 to 11);

- a local glacier would have occupied the Val-de-Travers region for thousands of years, later replaced by Alpine glaciers (layers 8–10);

- a clement period before the Last Glacial Maximum, in which the "pebble layer" is found, with sediments brought into the Grotte de Cotencher by a solifluction phenomenon (layer 12);

- a very cold, or even glacial, period around 70,000 BP, with a local glacier obstructing the cave's entrance (layers 14/17);

- a warming period, with a climate warmer than that found today in the region, between 127,000 and 110,000 BP, including the "brown layer" (layers 21 to 24).

See also

References

- ^ a b Chauvière, François-Xavier; Cattin, Marie-Isabelle; Deàk, Judit; Brenet, Frédéric (2018). "Le petit racloir moustérien: un retour à la grotte paléolithique de Cotencher (Rochefort, NE)" [The small Mousterian scraper: a return to the Paleolithic Cotencher cave (Rochefort, NE)] (PDF). NIKE Bulletin (in French): 32–35. Retrieved 2020-05-16. p. 33

- ^ Hofmann, Nadja (8 April 2016). "L'ours prend sa revanche au musée" [The bear takes its revenge at the museum] (PDF). Littoral Région (in French) (4503): 1–3. Retrieved 2020-05-16.

- ^ "Musée de l'Areuse, Boudry". le-musee.ch (in French). Retrieved 2020-05-16.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Bernard-Guelle, Sébastien (2004). "Un site moustérien dans le Jura suisse: la grotte de Cotencher (Rochefort, Neuchâtel) revisitée" [A Mousterian site in the Swiss Jura: the Cotencher cave (Rochefort, Neuchâtel) revisited]. Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française (in French). 101 (4): 741–769. doi:10.3406/bspf.2004.13066. ISSN 0249-7638. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ^ Geological map of Switzerland at 1/25,000 consulted on map.geo.admin.ch.

- ^ a b Miéville, Hervé. "Cotencher". DHS (in French). Retrieved 2025-08-05.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Chauvière, François-Xavier (2019). "La grotte de Cotencher (Rochefort, NE): Évolution des relevés topographiques et stratigraphiques (1867-2019)" [Cotencher Cave (Rochefort, NE): Evolution of topographic and stratigraphic surveys (1867-2019)] (PDF). Cavernes (in French): 4–24.

- ^ a b c d Deák, Judit; Preusser, Frank; Cattin, Marie-Isabelle; Castel, Jean-Christophe; Chauvière, François-Xavier (2019). "New data from the Middle Palaeolithic Cotencher cave (Swiss Jura): site formation, environment, and chronology". E&G Quaternary Science Journal. 67 (2): 41–72. Bibcode:2019EGQSJ..67...41D. doi:10.5194/egqsj-67-41-2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g Chauvière, François-Xavier; Deák, Judit; Cattin, Marie-Isabelle; Brenet, Frédéric; Juillard, Marc; Castel, Jean-Christophe; Oppliger, Julien; Preusser, Frank (2018). "La grotte de Cotencher: une (pré)histoire humaine et naturelle" [The Cotencher cave: a human and natural (pre)history]. Archéologie Suisse: Neuchâtel les nouvelles voies de l'archéologie (in French): 16–20.

- ^ Le Tensorer, Jean-Marie (1998). "Le milieu naturel au Paléolithique moyen : faune et végétation" [The natural environment in the Middle Paleolithic: fauna and vegetation]. Le Paléolithique en Suisse [The Palaeolithic in Switzerland] (in French). Grenoble: Éditions Jérôme Millon. pp. 99–110. ISBN 2-84137-063-1. Retrieved 29 July 2012. p. 99

- ^ Chauvière, François-Xavier; Cattin, Marie-Isabelle; Deàk, Judit; Brenet, Frédéric (2018). "Le petit racloir moustérien: un retour à la grotte paléolithique de Cotencher (Rochefort, NE)" [The small Mousterian scraper: a return to the Paleolithic Cotencher cave (Rochefort, NE)] (PDF). NIKE Bulletin (in French): 32–35. p. 34

- ^ "archeodev.ch". potree.org (in French). Retrieved 23 April 2020.