Giosafat Barbaro

Giosafat Barbaro (also spelled Giosaphat or Josaphat; 1413–1494) was a member of the Venetian patrician Barbaro family. He was a diplomat, merchant, explorer and travel writer.[1][2] He was unusually well-travelled for someone of his times, traveling to the Byzantine Empire, the Crimea, Russia, the Peloponnese, Poland, Germany, Albania, Persia, the Empire of Trebizond and Georgia.[3]

Family

Giosafat Barbaro was born in a palazzo on the northwest side of the Campo di Santa Maria Formosa in Castello, Venice.[4][5] His father was Antonio Barbaro, son of Domenico.[6][7] His father died when Giosafat was young,[8][9] while serving as Count and Captain of Scutari.[10] Antonio Barbaro wrote two wills, in 1423 and 1424, with his wife Franceschina and his brothers Andrea and Lorenzo Barbaro as executors. The wills show that Giosafat Barbaro had several siblings; Giacomo, Barbara, Carlo, Polissena, Daria, and Marina; with the last two sisters nuns in San Lorenzo.[10]

Giosafat Barbaro's mother was Franceschina Quartari, the daughter of Nicolo Quartari.[10][6] In her wills, written in 1421 and 1427, one of the bequests is to the Scuola di San Giosafat in Santa Maria Formosa.[10] Her second will mentions an additional daughter, Quirina, who was married to Andrea Barbo.[10] Barbaro's grandfather, Nicolo Quartari, was a wealthy silk merchant with a house and shop in the district of San Zulian.[11] In the 1379 land registry, he was registered for 5,500 lire, a level reached or exceeded by only about seventy commoners.[12] In the fifteenth century, Quartari brides brought dowries averaging 3100 ducats, though the legal limit was only 1600 ducats.[13]

Giosafat Barbaro was presented to the Balla d'Oro by his widowed mother Franceschina in 1431, which made him eligible to join the Venetian Senate.[8][14][9] We lack information on his education, but Barbaro was a skilled geographer, linguist, and negotiator.[15][9] He learned some Crimean Tatar, Persian, Arabic, and Greek during his travels.[16] Barbaro was a member of the Scuola Grande di San Marco.[17]

In 1434, he married Cenone (Nona) Duodo, daughter of Arsenio Duodo.[8][18] Tradition says the Duodo family was involved in trade with the Far East.[19]

Giosafat Barbaro's will of 1473 names his wife Cenone; his sister Polissena; Polisenna's husband Matteo Venier; his brother-in-law Niccolo Duodo; and his daughter Suordamor's husband, Natale Nadal; as executors.[19] In the will he mentions his children: Zuanne Antonio; Madaluzza; an adopted son Alvise; Suordamor; Chiara a natural-born nun at Santa Eufemia Monastery; and Franceschina, a nun at San Lorenzo.[19] In 1477, while Barbaro was Ambassador to Persia, his wife Cenone presented their son to the Balla d'Oro, indicating that Zuanne Antonio was born around 1459.[20] Giosafat Barbaro's will of 1492 names his wife Cenone; his son-in-law Natale Nadal; his daughter Anzola's husband, Marco Zulian; and his son Zuanne Antonio as executors.[21] The will mentions Giosafat's daughters Madaluzza, Chiara, and Franceschina; his son Zuanne Antonio's wife Suordamor Bembo, daughter of Pietro Bembo, and their daughter Lucrezia.[21][8] Giosafat's wife Cenone outlived him, writing a will in 1495.[18]

Travels to Tana

From 1436 to 1452 Barbaro traveled as a merchant to Tana on the Sea of Azov.[22][23][9] During this time the Golden Horde was disintegrating due to political rivalries.[24]

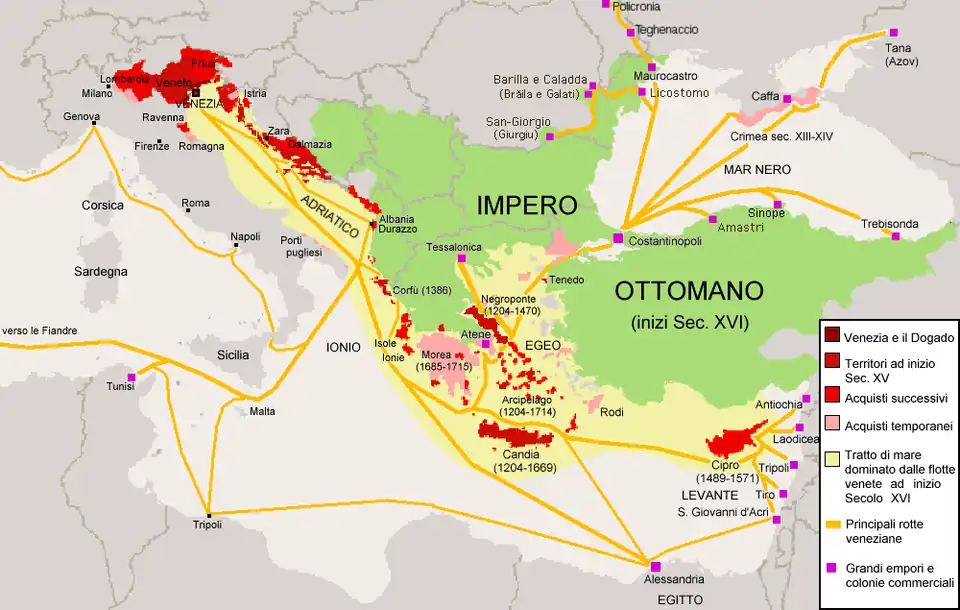

The conquest of Central Asia by the Mongols had opened the Black Sea as a trading hub for goods from China, Persia, and parts of Russia.[25] The Venetians settled in Soldaïa and Trebizond, but soon focused on Tana, which was better situated on both land and water trade routes.[26] They would later settle in Maurocastro as well.[27] Tana was the connecting point for the Danube, Polish and Persian trade routes, as well as the route beginning in Astrakhan that led to China.[28][29] Barbaro mentioned how six or seven trade galleys came from Venice every year for the silks and spices from Astakhan as well as other goods.[30] He also described annual shipments of 40,000 cattle to Central Asia and caravans with 6000 animals that went to India.[31] Among the goods traded in Tana were caviar, salted fish, wine, amber, salt, grain, fur, horses, and slaves,[31] as well as spices and silk.[32]

In July 1436, Barbaro started his first trip to Tana aboard one of the two trade galleys sent by the Senate of Venice.[33] Barbaro's father-in-law, Arsenio Duodo (also Diedo) had been elected Consul to Tana and was also traveling on the galleys.[34] The captains of the galleys initially refused to continue past Constantinople, though they eventually did reach Tana.[35] Initially, Consul Duodo had to stay in Constantinople at his own expense and was not reimbursed by the Senate until two years later. [35] Giosaphat Barbaro was Barbaro was probably not the first member of his family to travel to Tana, there are records of several members of the Barbaro family who had engaged in trade there before his arrival.[36]

In the fifteenth century Tana was a modestly-sized town mostly or entirely surrounded by walls with towers.[37] Commercial rivals Genoa and Venice fortified their sections of the town.[37] Byzantine and Russian quarters were near the Orthodox Church of St. Nicholas.[37] There were Jewish and Zichian quarters as well. [37] Barbaro owned a house inside the town of Tana.[27] The main source of income that Barbaro mentions are fisheries, located about 40 miles up the Don River from Tana.[31] [38][39] These fisheries (peschieres) were built along sections of the river bank where fish were caught and salted and caviar was prepared. Barbaro probably visited his peschieras often, in order to monitor the workers and ship the product back to Tana for transport back to Venice.[39] Barbaro also appears to have traded in precious stones, trading with Tatar merchants whose wares appear to have come from as far as China.[39]

Barbaro did not spend all of the years from 1436 to 1452 in Tartary.[15] Since there was regular trade between Venice and Tana at this time, it seems likely Barbaro went to Tana to trade and returned to Venice for the winter over this time.[40] He did not spend all of his time in Tana, from there he also traveled to the Don River, and to Georgia, Shirvan and Daghistàn.[16] Barbaro also traveled to Russia, where he visited Casan and Novogorod.[41] In November 1437, Barbaro heard of the burial mound of the last King of the Alans, about 20 miles up the Don River from Tana.[42][43]Barbaro and six other men, a mix of Venetian and Jewish merchants, hired 120 men to excavate the kurgan, which they hoped would contain treasure.[44][45][9] When the weather proved too severe, they returned in March 1438, but found no treasure.[44][45][9] Barbaro analytically and precisely recorded information about the layers of earth, coal, ashes, millet, and fish scales that composed the mound.[44][46] Modern scholarship concludes that it was not a burial mound, but a kitchen midden that had accumulated over centuries of use.[47] The remains of Barbaro's excavation was found in the 1920s by Russian archeologist Alexander Alexandrovich Miller.[47] Barbaro also described the worship and sacrifice of horses among the Maksha people. [29]

In 1438, the Great Horde under Küchük Muhammad advanced on Tana.[48] Arsenio Duodo, the Venetian Consul to Tana sent Giosafat Barbaro as an emissary to the Tatars to persuade them not to attack Tana.[22][49] Later, Barbaro was part of a group of less than fifty that drove off a hundred Circassian raiders.[50][51] Barbaro visited many cities in the Crimea, including Solcati, Soldaia, Cembalo, and Caffa.[22] In 1438, Barbaro traveled to Moscow up the Volga River, where he visited Kazan (Casan) and Novogorod, "which had already come under the power of the Muscovites" (che gia era venuta in potere de'Moscoviti).[52][a] He reported that Russian merchants sailed to Astrakhan every year.[53]

The Tatars attacked Tana in 1442, setting fire to the Venetian quarter, though many of the people survived due to the actions of Consul Marco Duodo, Arsenio's brother.[35] The fire started in the bazaar near the fortress and was fanned by a strong north wind.[54] Four breaches were made in the city walls, one by Barbaro himself, for people to escape, but even then women and children needed to be lowered over the walls by rope.[55] The fire burned for three hours until a combination of human efforts and rain extinguished it and over four hundred people died and the goods warehouses were destroyed.[55][56]

In 1442, there was also concern over the Turks raiding Venetian shipping.[55] Between that and the siege and fire at Tana, the new Consul Pietro Pesaro was stranded in Caffa for several weeks at his own expense before he was able to relieve Marco Duodo.[35] That July the Venetian Senate considered not sending trade galleys to Tana that year.[55] Instead they ordered Lorenzo Moro to use the war galleys from Negroponte and Naplia to escort the trade galleys commanded by Leonardo Duodo to and from Tana.[55] Giosafat Barbaro visited many cities in the Crimea, including Solcati, Soldaia, Cembalo, and Caffa.[22] He believed some of the local people were Gothic in origin based on one of his German servants being able to communicate with them in his own language.[22]

Barbaro stopped these travels when the Crimean Khanate became a client state of the Ottoman Turks.[57] Marco Basso, the last Venetian Consul before the fall of Constantinople left Tana before his term ended or his successor arrived.[35] In December 1452, the galleys returning from Tana, three large merchant galleys commanded by Alvise Diedo, and two smaller war galleys commanded by Gabriele Trevisano arrived in Constantinople. Their instructions were to return to Venice within ten days of the arrival of another Venetian galley from Trebizond. That galley, commanded by Giacomo Coco reached Constantinople on December 4, 1452, but Emperor Constantine XI and the Venetian Bailo Girolamo Minotto persuaded them to aid in the city's defense.[58] Barbaro returned to Venice in 1452, traveling by way of Russia, Poland, and Germany.[41][59][60] His route is believed to have been by way of Ryazan, Moscow, Troki, Warsaw, and Frankfurt on the Oder.[60][9]

The fall of Constantinople to the Turks in 1453 cut off the trade route to Tana.[30][61] Venice and other Italian states tried to re-establish trade in the Black Sea or find alternate routes, but were not successful.[30][62]

Political career

In 1434, Barbaro became an Avvocato at the Giudici al forestier (Court of the Foreigners).[18] This court's jurisdiction was cases involving foreigners, as well as cases involving maritime law. In 1446, Barbaro was elected to the Council of Forty (Quarantia).[40][63] In addition to being a court for criminal and civil cases, the Quarantia also administered the Venetian Mint and submitted financial plans for the approval of the Venetian Senate. In 1447, Barbaro was elected to the Console dei Mercanti (Merchants Council).[63] The Consoli dei Mercanti, which had five members, was responsible for promoting trade and had jurisdiction over it.

In 1448, Barbaro was appointed Provveditore (District Governor) of the trading colonies Modon and Corone in the Peloponnese and served until his resignation the following year.[40][63] In 1448, he nominated his father-in-law, Arsenio Duodo, for the office of Bailo of Constantinople (Resident Ambassador).[64]

In 1455, Barbaro discovered two Tatars being illegally kept as slaves by a Venetian wine merchant. Barbaro reported this to the Signori di Notte (Heads of the Criminal Court), who freed the men. They had been enslaved by Catalan pirates, escaped by sea, and then re-enslaved by the Venetian merchant. Barbaro recognized one of the two Tatars as someone he knew from Tana, a fellow survivor of the fire of 1442, and housed the pair for two months, until he could send them home to Tana.[65][39] In 1460, Giosafat Barbaro was elected Consul to Tana, as a successor to Alessandro Pasqualigo,but he declined the position.[33][61][9]

In 1462, Barbaro became part of the Ufficio alle Rason, which was divided into the Rason Vecchie and the Rason Nuove, each with three members. This government organization was responsible for auditing the accounts of government officials on the mainland and in Venice's overseas possessions, as well as the state-sponsored merchant convoys. The Ufficio alle Rason also had criminal jurisdiction in cases of embezzlement by government officials, dealt with debtors to the government, and were responsible for gifts to foreign rulers. In 1462,[66] and again in 1463 Barbaro was one of three officials of the Rason Vecchie responsible for presents from the Venetian Senate to Philip of Burgundy and Edward IV of England.[67] Also in 1462, as an official at the Rason Vecchie, he wrote to the Duke of Candia.[68] In early 1463 he made a trip to Dalmatia, to review the public credits regarding salt, in his capacity as Provveditore alle Rason Vecchie.[60]

In 1463, Barbaro was appointed Provveditore of Albania.[33][9] While there, Barbaro he fought with Lekë Dukagjini and Skanderbeg against the Turks.[69][70][71][72][73] His instructions were to immediately contact Skanderbeg to discuss strategy against the Ottomans and convince Lekë Dukagjini to join the Venetian-Albanian alliance.[74][70][75][72][73] Barbaro was among Skanderbeg's councilors due to his judgment and experience.[76] Barbaro made a comprehensive inspection of the territory, meeting with the leading nobles and trying to recruit them.[77][9]

On the advice of Barbaro and others, Skanderbeg travelled to the Papal States to request aid from Pope Paul II, but little aid was provided.[78] On his return, Skanderbeg asked Provveditore Barbaro for troops from Scutari and Barbaro provided five hundred footmen.[79] The Captain of the Gulf, Iacopo Venier, consulted Barbaro about possible Turkish moves.[80] Barbaro linked his forces with those of Dukagjini and Nicolo Moneta to form an auxiliary corps of 13,000 men which was sent to relieve the Second Siege of Krujë.[81] After Skanderbeg's death, Barbaro returned to Venice again.[33]

In 1468, Barbaro was one of seven men elected Savii sora la Piave et forno.[82] In 1469, Giosafat Barbaro was made Conte et Capetanio of Scutari, in Albania.[22][83][84][85] Buildings outside the walls were torn down to provide a clear field of fire and the rubble used to help form redoubts, ditches were cleared, cisterns filled, and the existing fortifications strengthened.[86] Barbaro was in command of 1200 cavalry, which he used to support Nicholas Pal Dukagjini against Dukagini's brother Lekë Dukagjini, who was supported by the Turks.[41] Lekë Dukagjini lost 800 men and was defeated.[87]

In 1470, Barbaro was succeeded as Conte, Capitano and Proevveditor of Scutari[88] by his friend Leonardo Boldù[89] In 1471, Barbaro was back in Venice, where he was one of the 41 senators chosen to act as electors, who selected Nicolo Tron as Doge.[52][90][91] That same year, Barbaro was elected Patron of the Arsenal, holding the position until 1473, when he was appointed ambassador to Persia.[91]

In 1472, Barbaro was appointed to a Zonta of 25 men, to assist the Council of Ten in investigating Cardinal Giovanni Battista Zeno and his mother, Elisabetta Barbo.[91] Cardinal Zeno was convicted of being head of a spy ring for the Papal States.[92]

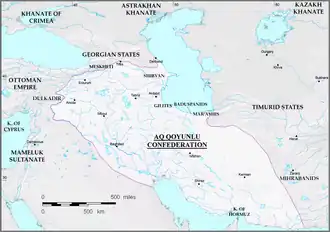

Ottoman–Venetian War

In 1463, the Venetian Senate, seeking allies in its first war against the Ottoman Empire, had sent Lazzaro Querini as its first ambassador to the Aq Qoyunlu state in Mesopotamia, the South Caucasus, and western Iran,[93] but he was unable to persuade Persia to attack the Turks.[94][95] Its ruler, Uzun Hasan, sent envoys to Venice in return.[93] After the Triarchy of Negroponte fell to the Ottomans, Venice, Naples, the Papal States, the Kingdom of Cyprus and the Knights Hospitaller signed an agreement to ally against them.[41]

In 1471, Ambassador Querini returned to Venice with Uzun Hassan's ambassador Murad.[93] The Venetian Senate voted to send another ambassador to Persia, choosing Caterino Zeno after two other men declined.[96] Zeno, whose wife was the niece of Uzun Hassan's wife, was able to persuade Hassan to attack the Turks. Hassan was successful at first, but there were no simultaneous attacks by any of the western powers, and the war turned against the Aq Qoyunlu.[97]

Ambassador to Persia

In 1473, Giosafat Barbaro, who was serving as Patron a l'Arsenal,[98][91] was selected as an additional ambassador to Persia,[9][99] due to his experience in the Crimean, Muscovy, and Tartary.[100][101] He also spoke Turkish and a little Persian.[33][102] A long and dangerous embassy like this would have benefited from the skills and knowledge Barbaro had acquired from his previous travels as a merchant, such as navigational skills and the ability to travel long distances.[103]

Barbaro was provided with an escort of ten men and an annual salary of 1800 ducats.[73] His instructions included urging admiral Pietro Mocenigo to attack the Ottomans and attempting to arrange naval cooperation from the Kingdom of Cyprus and the Knights of Rhodes.[73] Barbaro was also in charge of two galleys full of artillery, ammunition, and military personnel who were to assist Uzun Hassan.[104][101] With Barbaro was a Condottiero Captain Tommaso da Imola, in charge four constables and two hundred gunners and crossbowmen. Barbaro was also in charge of expensive gifts for Uzun Hassan.[105]

In February 1473, Barbaro and the Persian ambassador left Venice and traveled to Zadar, where they met with representatives of Naples and the Papal court.[73][101][9] From there, Barbaro and the others traveled by way of Corfu, Modon, Corone reaching Rhodes and then Cyprus, where Barbaro was delayed for a year.[73][60][9]

The Kingdom of Cyprus's position off the coast of Anatolia was in a key position for supplying, not just Uzun Hassan in Persia, but the Venetian allies of Caramania and Scandelore (present day Alanya) and the Venetian fleet under Pietro Mocenigo was used to defend communication lines to them.[106] King James II of Cyprus had attempted to ally with Caramania and Scandelore, as well as the Sultan of Egypt, against the Turks.[107][108] King James had also written to the Venetian Senate, stressing the need to support Persia against the Turks and his navy had cooperated with Admiral Mocenigo in recapturing the coastal towns of Gorhigos and Selefke.[109]

The Emir of Scandelore fell to the Turks in 1473 in spite of military aid from the Kingdom of Cyprus.[108] The power of Caramania was broken.[109]James II of Cyprus privately told Giosafat Barbaro he felt like he was trapped between two wolves, the Ottoman Sultan and the Egyptian Sultan.[108]The latter was James' liege lord, and not on friendly terms with Venice.[110] James II entered into negotiations with the Turks.[109] At first he refused to let the Venetian galleys with their munitions land in the port of Famagusta.[110] When Barbaro and the Venetian ambassador, Nicolo Pasqualigo, attempted to persuade James II to change his mind, the King threatened to destroy the galleys and kill every man on board.[110]

King James II of Cyprus died in July 1473, leaving Queen Catherine a pregnant widow.[111] James had appointed a seven-member council, which contained Venetian Andrea Cornaro, an uncle of the Queen, as well as Marin Rizzo and Giovanni Fabrice, agents of the Kingdom of Naples who opposed Venetian influence.[112] Queen Catherine gave birth to a son, James II in August 1473, with Admiral Pietro Mocenigo and other Venetian officials acting as godfathers.[113]

Once the Venetian fleet left, there was a revolt by pro-Neapolitan forces, which resulted in the deaths of the Queen's uncle and cousin.[113] The Archbishop of Nicosia, Juan Tafures the Count of Tripoli, the Count of Jaffa, and Marin Rizzo seized Famagusta, capturing the Queen and the newborn King.[113]

Barbaro and Bailo Pasqualigo were protected by the Venetian soldiers that had accompanied Barbaro. The conspirators made several attempts to persuade Barbaro to hand over the soldiers' arms. The Constable of Cyprus sent an agent, while the Count of Tripoli, the Archbishop of Nicosia, and the Constable of Jerusalem made personal visits. After consulting with Bailo Pasqualigo, they decided to disarm the men, but keep the weapons. Barbaro alerted the captains of the Venetian galleys in the harbor.[114] Barbaro also sent dispatches the Senate of Venice, warning them of events.[113] Later, Barbaro and the Venetian troops withdrew to one of the galleys.[115]

By the time Admiral Mocenigo returned to Cyprus, the rebels were quarreling among themselves and the people of Nicosia and Famagusta had risen against them.[116] The uprising was suppressed, those ringleaders who did not flee were executed, and Cyprus became a Venetian client state.[106] The Venetian Senate authorized the troops and military that had accompanied Giosafat Barbaro to stay in Cyprus.[117] The fleet under Admiral Mocenigo captured Selefke and other parts of the coast of Asia Minor. Barbaro took part in this campaign, but was unable to find a safe route to move the men and munitions to Persia.[118][119] When the mainland and island castles of Corycus were captured, Barbaro studied the Armenian inscriptions in them,[120][121][122] describing the castles and ruins.[123]

Giosafat Barbaro was still in Cyprus in December 1473, and the Venetian Senate sent a letter, telling Barbaro to complete his journey, as well as sending another ambassador, Ambrogio Contarini to Persia.[124] Barbaro and the Persian ambassador left Cyprus in February 1474 disguised as Muslim pilgrims.[124][125] The Papal and Neapolitan envoys did not accompany them.[121][9] Barbaro landed in Caramania, where the King warned them that the Turks held the territory they would need to travel through.[120][126] After landing in Cilicia, Barbaro's party avoided Ottoman territory and traveled through Tarsus and Adana in the lands of the Ramazanids.[127] They then passed through the Aq Qoyunlu cities of Orfa, Birecik, and Mardin.[120][121][122] In Mardin, Barbaro was hospitalized at a hospital built by Jahangir Aq Qoyunlu, the brother of Uzun Hasan Bey. Barbaro reported that meals were provided to the patients, and if the patient was a prominent figure, carpets, each worth over 100 ducats, were spread under their feet.[128] While in Mardin, Barbaro described an encounter with a Dervish.[129] Barbaro an his party then traveled through Hasankeyf, Siirt, and Hizan.[120][121][122]

After leaving Hizān, in the Taurus Mountains of Kurdistan, Barbaro's party was attacked by bandits.[121][122] Barbaro escaped on horseback, but he was wounded and several members of the group, including his secretary, Domenico Girardo, and the Persian ambassador, Hadji Mehmet, were killed, and their goods were plundered.[130][125][122][9] From there, Barbaro travelled through Khoy and Vastan.[122][128] As they neared Tabriz, Barbaro and his interpreter were assaulted by Turcomans after refusing to hand over a letter to Uzun Hassan.[130] Barbaro and his surviving companions finally reached Hassan's court in April 1474.[131]

Hasan had recently been defeated by the Ottomans at Baskent.[132] Ambassador Zeno recorded that the Ottomans won because of their firearms and that Uzun Hassan's Sardar and one of his sons died in the battle. [131] Hasan sent Ambassador Zeno, as well as the Hungarian and Polish ambassadors back to Europe to ask for aid.[131] Although Barbaro got on well with Uzun Hassan, he was unable to persuade the ruler to attack the Ottomans again.[97] Shortly afterwards, Hassan's son Ogurlu Mohamed rose in rebellion, seizing the city of Schiras.[133] Barbaro accompanied Uzun Hasan in the military expedition against Ogurlu Mohamed.[134] Barbaro traveled south from Tabriz, going through Soltaniyeh and Golpayegan before reaching for Isfahan.[135] The other Venetian ambassador, Ambrosio Contarini, arrived in Isfahan in August 1474.[97][131] Both ambassadors accompanied Uzun Hassan when he left Isfahan for Qum in November. In March 1875, they returned from Qum to Tabroz.[135] In June of that year, Uzun Hassan decided that Contarini would return to Venice with a report, while Giosafat Barbaro would stay in Persia.[136][137] In 1476, plague struck Persia and Uzun Hassan faced another revolt, this one by his brother Ruha.[131]

During his time in Perisa, Barbaro visited the ruins of Persepolis, which he incorrectly thought were of Jewish origin.[133][138] He also visited Tauris, Soldania, Isph, Cassan (Kascian), Como (Kom), Yezd, Shiraz and Baghdad.[125] Giosafat Barbaro was the first European to visit the ruins of Pasargadae, where he believed the local tradition that misidentified the tomb of Cyrus the Great as belonging to King Solomon's mother.[138][139]

Barbaro also traveled to the Caspian Sea, visiting Baku, Derbent, and Strava.[140] He traveled the trade route between Trebizond and Tauris and visited Arzingan (Erzingan) Carputh (Kharput), and Hall (Haladag).[140] When the Persians attacked the Kingdom of Georgia Barbaro accompanied the expedition and was able to visit Tiflis, Cothatis, and Scander.[140][95]

Return to Venice

The Venetian Senate decided to recall Barbaro in 1477, with the information probably reaching him by that autumn.[137] Barbaro initially tried to return to Venice by way of Russia, but in the Crimean Khanate the situation was so chaotic that Barbaro decided to return to Tabriz.[141] In the winter of 1477–78 Crimea was conquered from Khan Nur Devlet, by Janibeg, the son Mahmud bin Küchük. After Nur Devlet expelled Janibeg and regained the throne, the Ottomans released Meñli I Giray, who with their backing took the land from his older brother Nur Devlet. During this time, Barbaro met the Genoese Pietro di Guasco, who had fled to Persia after the fall of Kaffa to the Ottomans, giving us an account of that event.[9]

Barbaro was the last Venetian ambassador to leave Persia, after Uzun Hassan died in January 1478.[57][142] By this point only one of Barbaro's entourage was left.[143] While Hassan's sons fought each other for the throne, Barbaro hired an Armenian guide and escaped from Tabriz, traveling through Erzerum, Çemişgezek, Arapgir, Malatya, and Aleppo, before reaching Beirut.[57][142][144][140][145][9] From Beirut he traveled by sea to Cyprus and from there to Venice, arriving in 1479.[145][9]

After his return, Barbaro defended himself against complaints that he had spent too much time in Cyprus before going to Persia.[33] Barbaro's report included not just political and military matters, but discussed Persian agriculture, commerce, and customs.[140] In 1479, Barbaro was appointed Governor of Revenue.[146] In 1481, he became part of the Council of Ten.[147]

From 1482 to 1484, Giosafat Barbaro served as Captain of Rovigo and Provveditore of all Polesine,[147][9] an area which had recently been captured in the War of Ferrara.[148][149] Polesine had been ravaged by the War. Barbaro reduced taxes and forgave debts, while organizing the repair of fortress walls, for which the Council of Rovigo formally thanked him.[39] The Council of Ten ordered Barbaro to remove people of uncertain loyalty to the Republic from Rovigo, Lendinara, and Badia, an order Barbaro appears to have contested.[150] The Council also criticized Barbaro for his handling of Giovanni of Mirandola, abbot of the Abbey of Vangadizza.[150] In 1484, Barbaro was one of ten nobles handling taxes to pay for the War.[151]

In 1487, Barbaro supported Francesco Zane as Bailo of Durazzo.[151] In 1488, he became an Auditor officii Supragastaldionum loco Procuratorum, which was an appellate court for civil cases.[151] Later that year, Barbaro was elected Senior Magizatrate for the Sestiere of Castello and one of the Councilors of Doge Agostino Barbarigo[149][21][9] Barbaro became an Auditor officii Supragastaldionum loco Procuratorum again in 1490.[21] In 1492, he was a candidate for the office of Procurator of Saint Mark.[152] Barbaro died in 1494 and was buried in the Church of San Francesco della Vigna.[70][152][9] The grave marker appears to have been destroyed when Naopeon turned the chirch into a barracks, but copy of the inscription was preserved: "Sepultura M(agnifici) D(omini) Iosaphat Barbaro, de confinio sante Marie Formoxe, et eius heredum. 1494".[39][9]

Writing

In 1487, Barbaro wrote an account of his travels.[71][72][70][9][9] In it, he mentions being familiar with the accounts of Niccolò de' Conti and John de Mandeville. In addition to discussing the places he had traveled, Barbaro also included information on India and China that he obtained from people who had traveled there.[95] Giosafat Barbaro showed skill in observing unfamiliar places and reporting on them.[138][153] In addition to reporting on the state of commerce and agriculture in the places he visited, Barbaro described religious observations, funeral rites, and other customs.[140] His account "is still valuable for its important contributions towards the history of the commerce and geography of the middle ages".[153] Barbaro's account provided more information on Persia and its resources than that of Contarini.[102] Barbaro also did not dwell as much on the dangers and difficulties that he faced.[39] Much of Barbaro's information about the Kipchak Khanate, Persia, and Georgia is not found in any other sources.[57]

In the first part, Barbaro provides information on the daily life, social, military, economic, cultural, customs, and traditions of the peoples living around Tana, especially the Tatars.[154][9] The work describes agricultural production in Tana and its surroundings, as well as the differences in economic and dietary habits between nomadic and settled people.[155] The work provides information on the commercial activities of Genoese and Venetian merchants in Crimea and the Sea of Azov, the animal and silk trade between the Sea of Azov and its surroundings with Persia and Syria, and the salt trade with Moscow.[156] Barbaro provided a more balanced portrayal of the peoples he met than most writers of his time.[95] In his writings, he treated foreigners with respect regardless of their culture.[39]

The second part of his account covers Persia: Uzun Hasan's diplomatic and military activities,[95] information about the dynasty, trade routes, and the economy.[9] Barbaro also mentions festivals and court spectacles, as well as gifts sent to Uzun Hassan from India: a lion, two elephants, a tiger, and a giraffe.[95] The work also included information about the cities of Tabriz, Isfahan, Shiraz, Hom, Yazd, Hormuz and Baku, as well as the ruins of the ancient city of Persepolis and places such as Naqsh-e Rustam.[156]

Barbaro's account of his travels, entitled Viaggi fatti da Vinetia, alla Tana, in Persia was first published from 1543 to 1545 by the sons of Aldus Manutius.[157][57][9] It is included Giovanne Baptista Ramusio's 1559 Collection of Travels as Journey to the Tanais, Persia, India, and Constantinople.[72][158][9]Ramusio divided the work into two sections, Il Viaggio della Tana and Viaggio di Messer Iosafa Barbaro, Gentiluomo Venziano, nella Persia Parte Seconda, and broke thse sections into short chapters.[159] Ramusio's version also included a letter written by Barbaro in 1491 to the Bishop of Padua, Pietro Barozzi, where Barbaro described balcatran an herb consumed by the Tatars that Barbaro had also found when stationed in Croatia.[125][160]

The scholar and courtier William Thomas translated Ramusio's version into English for the young King Edward VI under the title 'Travels to Tana and Persia' and also includes the account of Barbaro's fellow ambassador to Persia, Ambrogio Contarini.[161] This work was republished in London in 1873 by the Hakluyt Society.[162][163][9] and a Russian language edition was published in 1971.[164] In 1583, Barbaro's account was published by Filippo Giunti in Volume Delle Navigationi Et Viaggi along with those of Marco Polo and Kirakos Gandzaketsi's account of the travels of Hethum I, King of Armenia.[165]

In 1601, a Latin extract by Jacob Geuder von Herolzburg of Barbaro's and Contarini's accounts was included in Pietro Bizzarri's Rerum Persicarum Historia along with accounts by accounts by Bonacursius, Jacob Geuder von Heroldsberg, Giovanni Tommaso Minadoi, and Henricus Porsius; which was published in Frankfurt.[166][9] in 2005, Barbaro's account was also published in Turkish as 'Anadolu'ya ve İran'a seyahat'.[167] In 1647, this extract of Barbaro's work was published by Joannes de Laet.[168] It also appeared in Georgii Hornii Ulyssea in 1671.[168] In 1788, an annotated extract of Barbaro's work was published by Johann Reinhold Forster in Histoire des découvertes et des voyages faits dans le Nord.[153] It also appears in Johann Beckmann's Litteratur der älteren Reisebeschreibungen, published in 1810,[153] and Di Marco Polo e degli altri viaggiatori veneziano, published in 1818 by Giacinto Placido Zurla.[153] In 1836, Vasily Semanov published a translation of Barbaro's work into Russian.[169] In 2005, part Barbaro's account was also published in Turkish as Anadolu'ya ve I?ran'a seyahat.[170]

Giosafat Barbaro's dispatches to the Venetian Senate were compiled by Enrico Cornet and published as Lettere al Senato Veneto in 1852 in Vienna.[171] and Le guerre dei Veneti nell' Asia 1470-1474: Documenti cavati dall' Archivio ai frari in Venezia in 1856.[172]

Barbaro also discussed his travels in a letter written in 1491 to the Bishop of Padua, Pietro Barozzi.[125]

In popular culture

He is one of the historical characters who appear in Dorothy Dunnett's novel Caprice and Rondo in the House of Niccolò series. In the game Civilization V he is a great merchant for the Venetians.

Notes

- ^ In the reference it does not specify which "Novogorod" whether it is the one at Lake Ilmen or "Nizhny Novgorod" on Volga, but it is mentioned in context of traveling around Volga and Oka rivers. "Veliky Novgorod" at lake Ilmen is nowhere near the area. The Duchy of Nizhny Novgorod was annexed by Muscovy in 1392 (Principality of Nizhny Novgorod-Suzdal).

References

- ^ A new general biographical dictionary, Volume 3, Hugh James Rose, Henry John Rose, 1857, pg. 137 ISBN 978-0-333-76094-9

- ^ A. M. Piemontese, "'Barbaro, Giosafat". Encyclopædia Iranica, Vol. III, Fasc. 7, p. 758.

- ^ Una famiglia veneziana nella storia: i Barbaro, Michela Marangoni, Manlio Pastore Stocchi, Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti, 1996, pg. 120, ISBN 978-88-86166-34-8

- ^ Die persische Karte: venezianisch-persische Beziehungen um 1500; Reiseberichte venezianischer Persienreisender, Otto H. Storz, Berlin, 2009, p.39 ISBN 978-3-643-10073-3

- ^ Almagià, Roberto (1964). "Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani" (PDF). European University Institute Department of History and Civilization.

- ^ a b Marangoni & Stocchi 1996, pp. 23.

- ^ "I Viaggi in Persia degli ambasciatori veneti Barbaro e Contarini", Laurence Lockhart; Raimondo Morozzo della Rocca; Maria Francesca Tiepolo, Venezia, A spese della R. Deputazion, 1973, pg. 16 [1]

- ^ a b c d Storz 2009, pp. 39.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad Almagià 1964.

- ^ a b c d e Lockhart, Morozzo della Rocca & Tiepolo 1973, pp. 36.

- ^ "La comunità dei lucchesi a Venezia", Luca Molà, Venezia, Istituto veneto di scienze, lettere ed arti, 1994, pg. 181 [2]

- ^ Molà & Istituto veneto di scienze 1996, pp. 181.

- ^ "A Renaissance of Conflicts: Visions and Revisions of Law and Society in Italy and Spain", John A. Marino, Thomas Kuehn; Centre for Reformation and Renaissance Studies, 2004, pg. 268 [3]

- ^ [4] Studi biografici e bibliografici sulla storia della geografia in Italia], Roma, Società geografica italiana; 1882, pg. 140

- ^ a b Storz 2009, pp. 40.

- ^ a b Lockhart, Morozzo della Rocca & Tiepolo 1973, pp. 18.

- ^ "Venetian narrative painting in the age of Carpaccio", Patricia Fortini Brown, New Haven, Yale University Press, 1988., pg. 74 [5], ISBN 0300040253

- ^ a b c Lockhart, Morozzo della Rocca & Tiepolo 1973, pp. 37.

- ^ a b c Lockhart, Morozzo della Rocca & Tiepolo 1973, pp. 260.

- ^ Lockhart, Morozzo della Rocca & Tiepolo 1973, pp. 47.

- ^ a b c d Lockhart, Morozzo della Rocca & Tiepolo 1973, pp. 52.

- ^ a b c d e f Società geografica italiana 1882, pp. 140.

- ^ [6] Biographie universelle, ancienne et moderne, J Fr Michaud; Louis Gabriel Michaud, Paris, Chez Michaud Freres Libraires, 1811, pg. 327

- ^ Marangoni & Stocchi 1996, pp. 120.

- ^ "Les Vénitiens à La Tana (Azov) au XVe siècle", Bernard Doumerc, Cahiers du monde russe et soviétique, Issue 28, 1987, pg. 5 [7]

- ^ Doumerc 1987, pp. 5.

- ^ a b Doumerc 1987, pp. 9.

- ^ "Les Italiens et la découverte de la Moscovie ", E. Pommier, Mélanges d'archéologie et d'histoire, Issue 65, 1953, pg. 251 [8]

- ^ a b Lockhart, Morozzo della Rocca & Tiepolo 1973, pp. 17.

- ^ a b c Pommier 1953, pp. 251.

- ^ a b c Doumerc 1987, pp. 10.

- ^ Khvalkov, Ievgen Alexandrovitch. "The colonies of Genoa in the Black Sea region: evolution and transformationo" (PDF). European University Institute Department of History and Civilization. p. 138. Retrieved July 27, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f Storz 2009, pp. 44.

- ^ "Delle Crimea", Michele Giuseppe Canale -, 1855, p. 477 [9]

- ^ a b c d e Doumerc 1987, pp. 8.

- ^ Наука, М. (1971). "Барбаро и Контарини о России". Retrieved July 27, 2025.

- ^ a b c d Khvalkov 2015, pp. 139.

- ^ Khvalkov 2015, pp. 414.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Наука 1971.

- ^ a b c Storz 2009, pp. 41.

- ^ a b c d Società geografica italiana 1882, pp. 141.

- ^ Black Sea, Neal Ascherson, New York, Farrar, Straus and Girouxg, 1996, pg. 128, ISBN 978-0-8090-3043-9

- ^ "Venice & antiquity: the Venetian sense of the past", Patricia Fortini Brown, New Haven, Conn. ; London: Yale University Press, 1996, pg. 152 [10], ISBN 0300067003

- ^ a b c Ascherson 1996, pp. 128.

- ^ a b Fortini Brown 1996, pp. 152.

- ^ Fortini Brown 1996, pp. 153.

- ^ a b Ascherson 1996, pp. 129.

- ^ [11] History of the Mongols: from the 9th to the 19th century], Sir Henry Hoyle Howorth, 1876, The University of California, pg. 295

- ^ Mehmed the Conqueror & His Time, Franz Babinger, Trans. Ralph Manheim, Princeton University Press; 1992, p.319 ISBN 978-0-691-01078-6

- ^ Howorth 1882, pp. 295.

- ^ Khvalkov 2015, pp. 262.

- ^ a b Società geografica italiana 1882, pp. 110.

- ^ Blum, Jerome (21 April 1971). Lord and Peasant in Russia: From the Ninth to the Nineteenth Century. Princeton University Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-691-00764-9.

- ^ "Revue de l'Orient latin, Volume 7", Charles Henri Auguste Schefer, E. Leroux, 1899, pg. 65 [12]

- ^ a b c d e Schefer 1899, pp. 65.

- ^ Gullino, Giuseppe (1996). "Le frontiere navali". Retrieved July 27, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e Michaud 1811, pp. 327.

- ^ "The Papacy and the Levant: 1204 - 1571", Kenneth M. Setton, American Philosophical Society, 1976, pg. 111 [13], ISBN 0871691140

- ^ A General History and Collection of Voyages and Travels, Robert Kerr, 2007, pg. 624

- ^ a b c d Lockhart, Morozzo della Rocca & Tiepolo 1973, pp. 19.

- ^ a b Marangoni & Stocchi 1996, pp. 119.

- ^ Doumerc 1987, pp. 16.

- ^ a b c Lockhart, Morozzo della Rocca & Tiepolo 1973, pp. 39.

- ^ Lockhart, Morozzo della Rocca & Tiepolo 1973, pp. 40.

- ^ Howorth 1882, pp. 300.

- ^ ""Archives of Venice"". Retrieved July 8, 2025.

- ^ ""Archives of Venice"". Retrieved July 8, 2025.

- ^ Lockhart, Morozzo della Rocca & Tiepolo 1973, pp. 42.

- ^ "Turcica, Volume 31", Université de Strasbourg, 1999, pg. 268

- ^ a b c d Società geografica italiana 1882, pp. 144.

- ^ a b Enciclopedia storico-nobiliare italiana, Volume 7, Vittorio Spreti, Arnaldo Forni, 1981, pg. 276

- ^ a b c d Rose & Rose 1857, pp. 137.

- ^ a b c d e f Babinger 1992, pp. 319.

- ^ Université de Strasbourg 1999, pp. 268.

- ^ "Enciclopedia storico-nobiliare italiana, Volume 7", Vittorio Spreti, Arnaldo Forni, 1981, pg. 276 [14]

- ^ "George Castriot, surnamed Scanderbeg, king of Albania", Clement Clarke Moore, New York: D. Appleton & Co, 1850, pg. 351 [15]

- ^ "Das venezianische Albanien (1392-1479)", Oliver Jens Schmitt, Oldenbourg, 2001, pg. 607 [16], ISBN 3486565699

- ^ Moore 1850, pp. 354.

- ^ Moore 1850, pp. 355.

- ^ Lockhart, Morozzo della Rocca & Tiepolo 1973, pp. 43.

- ^ Le istorie albanesi, Volume 1, Francesco Tajani, Salerno, Fratelli Jovane, 1886., pg. 120

- ^ Le Vite Dei Dogi 1423-1474, Volume II, Marin Sanudo, Venezia 2004, pg. 96

- ^ Babinger 1992, pp. 261.

- ^ Sanudo 2004, pp. 88.

- ^ Lockhart, Morozzo della Rocca & Tiepolo 1973, pp. 44.

- ^ Schmitt 2001, pp. 536.

- ^ "Saggio Sulla Storia Civile, Politica, Ecclesiastica E Sulla Corografia", Cristoforo Tentori, Strorti, Venice, 1785, pg. 229 [17]

- ^ Lockhart, Morozzo della Rocca & Tiepolo 1973, pp. 45.

- ^ Beverley 1999, pp. 260.

- ^ Sanudo 2004, pp. 168.

- ^ a b c d Lockhart, Morozzo della Rocca & Tiepolo 1973, pp. 46.

- ^ Domenico Malipiero, Annali veneti dall'anno 1457 al 1500, Volume 2 (Firenze: Vieusseux, 1844), pp. 661-662.

- ^ a b c Babinger 1992, pp. 305.

- ^ The Cambridge history of Iran, William Bayne Fisher, Peter Jackson, Laurence Lockhart, New York: Cambridge University Press, 1986, p.377 ISBN 978-0-521-20094-3

- ^ a b c d e f Marangoni & Stocchi 1996, pp. 124.

- ^ Babinger 1992, pp. 306.

- ^ a b c Fisher 1986, pp. 377.

- ^ Sanudo 2004, pp. 167.

- ^ [18], Le frontiere navali, Giuseppe Gullino, Enciclopedia Treccani , 1996

- ^ Historical account of discoveries and travels in Asia, Hugh Murray, Edinburgh, A. Constable and Co; 1820., p.10

- ^ a b c Marangoni & Stocchi 1996, pp. 19.

- ^ a b Fisher 1986, pp. 378.

- ^ Beverley 1999, pp. 175.

- ^ [19], He Kypros kai hoi Staurophories, Nikos Kureas; International Conference Cyprus and the Crusades (1994, Leukosia), pg. 161

- ^ "Archivio veneto", Rinaldo Fulin, Venezia, A spese della R. Deputazion, 1914, pg. 47 [20]

- ^ a b Kureas 1994, pp. 161.

- ^ A history of Cyprus, Volume 3, Sir George Francis Hill, Cambridge University Press, 1952, pg. 623

- ^ a b c Hill 1952, pp. 623.

- ^ a b c Hill 1952, pp. 624.

- ^ a b c Hill 1952, pp. 626.

- ^ Venetian studies, Horatio Forbes Brown, London, K. Paul, Trench & Co, 1887, p.310

- ^ Brown 1887, pp. 311.

- ^ a b c d Brown 1887, pp. 312.

- ^ Hill 1952, pp. 674.

- ^ Hill 1952, pp. 682.

- ^ Brown 1887, pp. 313.

- ^ Hill 1952, pp. 662.

- ^ "E.J. Brill's first encyclopaedia of Islam", M. Th. Houtsma, New York, E.J. Brill, 1993, p.1067 [21] ISBN 9004097961

- ^ "Cilicia and its governors", William Burckhardt Barker;London: Ingram, Cooke, and Co., 1853., p.61 [22]

- ^ a b c d Murray 1820, pp. 10.

- ^ a b c d e Babinger 1992, pp. 326.

- ^ a b c d e f Lockhart, Morozzo della Rocca & Tiepolo 1973, pp. 20.

- ^ "The Funerary Monuments of Rough Cilicia and Isauria", Yasemin Er Scarborough, BAR Publishing, Oxford, 2017, p.6 [23] ISBN 9781407315287

- ^ a b Babinger 1992, pp. 321.

- ^ a b c d e Società geografica italiana 1882, pp. 142.

- ^ Società geografica italiana 1882, pp. 120.

- ^ [24] ,BATILI SEYYAHLARIN GÖZÜYLE MARDİN VE ÇEVRESİ, YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ, HARRAN ÜNİVERSİTESİ, 2010, pg. 34

- ^ a b TEZİ 2010, pp. 34.

- ^ TEZİ 2010, pp. 34–35.

- ^ a b Murray 1820, pp. 12.

- ^ a b c d e Houtsma 1993, pp. 1067.

- ^ Marangoni & Stocchi 1996, pp. 125.

- ^ a b Murray 1820, pp. 15.

- ^ Marangoni & Stocchi 1996, pp. 68.

- ^ a b Lockhart, Morozzo della Rocca & Tiepolo 1973, pp. 21.

- ^ Murray 1820, pp. 19.

- ^ a b Lockhart, Morozzo della Rocca & Tiepolo 1973, pp. 22.

- ^ a b c Fortini Brown 1996, pp. 156.

- ^ Encyclopedia Americana, Volume 21, New York, Americana Corp; 1965, pg.321

- ^ a b c d e f Società geografica italiana 1882, pp. 143.

- ^ Lockhart, Morozzo della Rocca & Tiepolo 1973, pp. 22–23.

- ^ a b Babinger 1992, pp. 322.

- ^ Marangoni & Stocchi 1996, pp. 128.

- ^ Murray 1820, pp. 16.

- ^ a b Lockhart, Morozzo della Rocca & Tiepolo 1973, pp. 23.

- ^ Lockhart, Morozzo della Rocca & Tiepolo 1973, pp. 48.

- ^ a b Lockhart, Morozzo della Rocca & Tiepolo 1973, pp. 49.

- ^ Dei rettori veneziani in Rovigo: illustrazione storica con documenti, Giovanni Durazzo, Venezia, Tip. del Commercio, 1865, pg. 16

- ^ a b Storz 2009, pp. 45.

- ^ a b Lockhart, Morozzo della Rocca & Tiepolo 1973, pp. 50.

- ^ a b c Lockhart, Morozzo della Rocca & Tiepolo 1973, pp. 51.

- ^ a b Lockhart, Morozzo della Rocca & Tiepolo 1973, pp. 54.

- ^ a b c d e Herberstein 1851, pp. lxvii.

- ^ [25] Barbaro, Josaphat ve Seyahatnamesi, Zafer Korkmaz, Online Türkiye Turizm Ansiklopedisi, 2020, pg. 138

- ^ Korkmaz 2015.

- ^ a b Korkmaz 2020.

- ^ Barbaro, Giosafat, Viaggi fatti da Vinetia, alla Tana, in Persia, in India, et in Costantinopoli, ... [Journeys made from Venice to Tanais, to Persia, to India, and to Constantinople], (Venice (Vinegia), (Italy): Aldus Manutius, 1545). [in Italian]

- ^ Universal Pronouncing Dictionary of Biography and Mythology. Vol. I., pg.262, Thomas Joseph, Philadelphia, PA, USA: J. B. Lippincott and Co., 1870

- ^ Storz 2009, pp. 82.

- ^ "Notes upon Russia", Sigmund Herberstein, Hakluyt Society, 1851, pg. lxviii [26]

- ^ Filippo Bertotti, "'Contarini, Ambrogio". Encyclopædia Iranica, Vol. VI, Fasc. 2, p. 220.

- ^ Barbaro, G., Stanley of Alderley, H. Edward John Stanley., Contarini, A. (1873). Travels to Tana and Persia. London: Printed for the Hakluyt Society.

- ^ Worldcat. OCLC 217119736.

- ^ Worldcat. OCLC 236220401.

- ^ Worldcat. OCLC 312110049.

- ^ Worldcat. OCLC 255858576.

- ^ Worldcat. OCLC 62732381.

- ^ a b Herberstein 1851, pp. lxviii.

- ^ Herberstein 1851, pp. lxix.

- ^ ""Worldcat"". Retrieved 2010-04-14.

- ^ "Worldcat". Retrieved 2010-04-14.

- ^ "Worldcat". Retrieved 2025-07-22.

Bibliography

- Ascherson, Neal (1996). Black Sea. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Babinger, Franz (1992). Mehmed the Conqueror & His Time. Princeton University Press.

- Donazollo, Pietro (1929). I Viaggiatori veneti minori. Studio bio-bibliografico. Reale Societa Geografica Italiana.

- Doumerc, Bernard (1987). Les Vénitiens à La Tana (Azov) au XVe siècle. Cahiers du monde russe et soviétique, Issue 28, 1987.

- Brown, Horatio Forbes (1887). Venetian studies. K. Paul, Trench & Co.

- Fisher, William Bayne; Jackson, Peter; Lockhart, Laurence (1857). A new general biographical dictionary, Volume 3. T. Fellowes.

- Fortini Brown, Patricia (1988). Venetian narrative painting in the age of Carpaccioi. Yale University Press.

- Fortini Brown, Patricia (1996). Venice & antiquity: the Venetian sense of the past. Yale University Press.

- Herberstein, Sigmund (1851). Notes upon Russia. Hakluyt Society.

- Hill, George Francis (1952). A history of Cyprus, Volume 3. Cambridge University Press.

- Houtsma (1993). E.J. Brill's first encyclopaedia of Islam. E.J. Brill.

- Howorth, Henry Hoyle (1996). History of the Mongols: from the 9th to the 19th century. The University of California.

- Khvalkov, Ievgen Alexandrovitch (2015). "The colonies of Genoa in the Black Sea region: evolution and transformation" (PDF). Florence: European University Institute Department of History and Civilization. Retrieved July 19, 2025.

- Lockhart, Laurence; Morozzo della Rocca, Raimondo; Tiepolo, Maria Francesca (1973). I Viaggi in Persia degli ambasciatori veneti Barbaro e Contarini. Istituto poligrafico dello Stato, Libreria.

- Michaud, J Fr; Michaud, Louis Gabriel (1811). Biographie universelle, ancienne et moderne. Chez Michaud Freres Libraires.

- Moore, Clement Clarke (1850). George Castriot, surnamed Scanderbeg, king of Albania. D. Appleton & Co.

- Murray, Hugh (1820). Historical account of discoveries and travels in Asia. A. Constable and Cos.

- Marangoni, Michela; Stocchi, Manlio Pastore (1996). Una famiglia veneziana nella storia: i Barbaro. Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti.

- Pommier, E. (1953). Les Italiens et la découverte de la Moscovie. IMélanges d'archéologie et d'histoire, Issue 6.

- Rose, Hugh James; Rose, Henry John (1857). A new general biographical dictionary, Volume 3. T. Fellowes.

- Sanudo, Marin (2004). Le Vite Dei Dogi 1423-1474, Volume I.

- Schefer, Charles Henri Auguste (1899). Revue de l'Orient latin, Volume 7. E. Lerou.

- Schmitt, Oliver Jens (2001). Das venezianische Albanien (1392-1479). Oldenbourg.

- Società geograf ica italiana (1882). Studi biografici e bibliografici sulla storia della geografia in Italia'. Società geografica italiana.

- Storz, Otto-Hermann (2009). Die persische Karte: venezianisch-persische Beziehungen um 1500; Reiseberichte venezianischer Persienreisender.

- Université de Strasbourg (1999). Turcica, Volume 31. Université de Strasbourg.