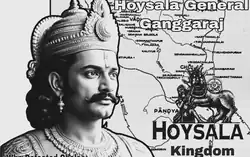

Ganggaraj

Ganggaraj was an 11th–12th-century minister and general of the Hoysala Empire under King Vishnuvardhana. He led the war against the Cholas. He is remembered for his key military campaigns against the Cholas, and for his patronage of Jainism, especially in Shravanabelagola.[1] It is said that his role was more important in all three wars than even King Vishnuvardhana himself.[2]

He was very close to Vishnuvardhana. In inscriptions he is called "Pada-Padma-Jivi" (one who lives at the king's feet).[3]

Military career and campaigns

Ganggaraj served as a trusted general of Vishnuvardhana, playing a crucial role in consolidating Hoysala power and repelling Chola incursions. The Cholas at the time frequently attacked Gangavadi, reportedly destroying Jain temples around Talakadu.[4]

First Chola War

Frustrated by these incursions, Vishnuvardhana ordered Gangaraj to lead a major expedition against the Cholas. Ganggaraj successfully defeated the Chola commander Adiyamma[5] in battle near Talakadu, recovering large parts of Gangavadi province. Because of this victory, Vishnuvardhana earned the title Talakadugonda (Conqueror of Talakadu), but inscriptions highlight that Gangaraja’s role was even more important than that of Vishnuvardhana.[6] Pleased with this war, King Vishnuvardhana asked what reward he desired; Gangaraja requested the high-revenue village of Govindapadi,[7] which he donated for the maintenance and worship at the Jain center of Gommateshwara and Shravanabelagola, and for the construction of the Panchakuta Basadi at Kambadahalli.[8]

Nolambavadi and Chalukya Campaign

Ganggaraj also led successful campaigns to recapture parts of Nolambavadi from the Chalukyas. After victory, he asked Vishnuvardhana to grant the valuable "Parama" village,[9] which he donated for the maintenance of the Shasana Basadi and the Eredukatte Basadi at Shravanabelagola.[10]

Second Chola Campaign

In a later expedition, Ganggaraj again defeated the Cholas and Followed them deep into Tamil territory up to Vellore.[11] In gratitude, Vishnuvardhana offered him another grant, and Gangaraja requested land at "Bindiganavile Tirtha" or Kambadahalli, a major Jain center, which he donated to his guru Shubhachandra Siddhanta Deva for Jain religious use.[12]

Patronage and public works

Ganggaraj was a devout Jain who dedicated his military rewards to Dharma and the welfare of the people.[13] In the 12th century, he left Halebidu and spent his entire time with his family at Shravanabelagola.[14] He is credited with founding an agrahara in Jinanthapura, about 2 km from Shravanabelagola, where he lived with his mother Pochikabbe and his family, all ardent devotees of Jinas.[15]

Family and legacy

Inscriptions at Shravanabelagola mention his family’s contributions, including his sister Jakkiyabbe. They built the Gangasamudra tank and other public works to improve Shravanabelagola, including roads and lakes, earning lasting praise from Jain chronicles.[16] Historians note that the Hoysalas gained the dignity of an independent kingdom in part due to the campaigns and counsel of Vishnuvardhana’s trusted minister, Mantri Ganggaraj.[17]

Gangaraja is remembered as a key figure in developing Shravanabelagola into an important Jain center, with traditions saying that Jains and specially the people of Shravanabelagola will never forget the contributions of Mantri Ganggaraj, Mantri Chaundaraya, and Bhandari Ulla.[18]

Reference

- ^ Rice, B. Lewis (1903). Mysore Inscriptions. Bangalore: Government Press. pp. 42–44.

- ^ Settar, S. (1989). Shravanabelagola: History, Art, Architecture, and Inscription. New Delhi: Sharada Publishing House. p. 68.

- ^ Rice, B. Lewis (1903). pp. 42–44.

- ^ Foekema, Gerard (1996). A Complete Guide to Hoysaḷa Temples. Abhinav Publications. p. 19.

- ^ Foekema (1996), p. 19.

- ^ Settar (1989), p. 68.

- ^ Rice (1903), pp. 42–44.

- ^ Settar (1989), p. 68.

- ^ Rice (1903), pp. 42–44.

- ^ Rice (1903), pp. 42–44.

- ^ Foekema (1996), p. 19.

- ^ Settar (1989), p. 68.

- ^ Settar (1989), p. 68

- ^ Rice (1903), pp. 42–44.

- ^ Settar (1989), p. 72.

- ^ Rice (1903), pp. 42–44.

- ^ Coelho, H.D. (1958). The Hoysalas. Bangalore University Press. p. 57.

- ^ Settar (1989), p. 72.