GD 66

| Observation data Epoch J2000 Equinox J2000 | |

|---|---|

| Constellation | Auriga[2] |

| Right ascension | 05h 20m 38.32s[3] |

| Declination | +30° 48′ 23.9″[3] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 15.6[4] |

| Characteristics | |

| Evolutionary stage | white dwarf[5] |

| Spectral type | DA4.1[6] |

| U−B color index | −0.59[7] |

| B−V color index | +0.22[7] |

| Variable type | ZZA[4] |

| Astrometry | |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: +57.213[3] mas/yr Dec.: −122.348[3] mas/yr |

| Parallax (π) | 17.5116±0.0387 mas[3] |

| Distance | 186.3 ± 0.4 ly (57.1 ± 0.1 pc) |

| Absolute magnitude (MV) | 11.79[6] |

| Details | |

| Mass | 0.64±0.03[8] M☉ |

| Surface gravity (log g) | 8.05[9] cgs |

| Temperature | 11,980[9] K |

| Age | 1.2–1.7[8] Gyr |

| Other designations | |

| GD 66, 361 Aurigae, EGGR 572, WD 0517+30, WD 0517+307, 2MASS J05203829+3048239[10] | |

| Database references | |

| SIMBAD | data |

GD 66 or V361 Aurigae is a 0.64 solar mass (M☉)[8] pulsating white dwarf star located 170 light years from Earth[5] in the Auriga constellation. The estimated cooling age of the white dwarf is 500 million years.[8] Models of the relationship between the initial mass of a star and its final mass as a white dwarf star suggest that when the star was on the main sequence it had a mass of approximately 2.5 M☉, which implies its lifetime was around 830 million years.[8] The total age of the star is thus estimated to be in the range 1.2 to 1.7 billion years.[8]

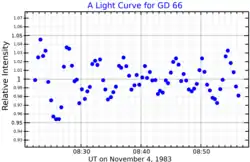

In 1983, Noël Dolez et al. discovered that GD 66 is a variable star, from photometric data obtained at Haute-Provence Observatory.[11] It was given its variable star designation, V361 Aurigae, in 1985.[12] The star is a pulsating white dwarf of type DAV, with an extremely stable period. Small variations in the phase of pulsation led to the suggestion that the star was being orbited by a giant planet which caused the pulsations to be delayed due to the varying distance to the star caused by the reflex motion about the system's centre-of-mass.[5] Observations with the Spitzer Space Telescope failed to directly detect the planet, which put an upper limit on the mass of 5–6 Jupiter masses.[8] Investigation of a separate pulsation mode revealed timing variations in antiphase with the variations in the originally-analysed pulsation mode.[13] This would not be the case if the variations were caused by an orbiting planet, and thus the timing variations must have a different cause. This illustrates the potential dangers of attempting to detect planets by white dwarf pulsation timing.[14]

References

- ^ Fontaine, G.; Wesemael, F.; Bergeron, P.; Lacombe, P.; Lamontagne, R. (July 1985). "The demise of mode identification in the pulsating DA white dwarf GD 66". The Astrophysical Journal. 294: 339–344. Bibcode:1985ApJ...294..339F. doi:10.1086/163301.

- ^ Roman, Nancy G. (1987). "Identification of a constellation from a position". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 99 (617): 695. Bibcode:1987PASP...99..695R. doi:10.1086/132034. Constellation record for this object at VizieR.

- ^ a b c d e Vallenari, A.; et al. (Gaia collaboration) (2023). "Gaia Data Release 3. Summary of the content and survey properties". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 674: A1. arXiv:2208.00211. Bibcode:2023A&A...674A...1G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202243940. S2CID 244398875. Gaia DR3 record for this source at VizieR.

- ^ a b Samus', N. N.; Kazarovets, E. V.; Durlevich, O. V.; Kireeva, N. N.; Pastukhova, E. N. (2017). "General catalogue of variable stars: Version GCVS 5.1". Astronomy Reports. 61 (1): 80. Bibcode:2017ARep...61...80S. doi:10.1134/S1063772917010085.

- ^ a b c Mullally, F.; et al. (2008). "Limits on Planets around Pulsating White Dwarf Stars". The Astrophysical Journal. 676 (1): 573–583. arXiv:0801.3104. Bibcode:2008ApJ...676..573M. doi:10.1086/528672. S2CID 123684051.

- ^ a b Gianninas, A.; Bergeron, P.; Ruiz, M. T. (2011). "A Spectroscopic Survey and Analysis of Bright, Hydrogen-rich White Dwarfs". The Astrophysical Journal. 743 (2): 138. arXiv:1109.3171. Bibcode:2011ApJ...743..138G. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/743/2/138.

- ^ a b Mermilliod, J. -C. (1987). "UBV Photoelectric Photometry Catalogue (1986): I. The Original data". Astronomy and Astrophysics Supplement Series. 71: 413. Bibcode:1987A&AS...71..413M.

- ^ a b c d e f g Mullally, F.; et al. (2009). "Spitzer Planet Limits around the Pulsating White Dwarf GD66". The Astrophysical Journal. 694 (1): 327–331. arXiv:0812.2951. Bibcode:2009ApJ...694..327M. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/694/1/327. S2CID 16241754.

- ^ a b Bergeron, P.; et al. (2004). "On the Purity of the ZZ Ceti Instability Strip: Discovery of More Pulsating DA White Dwarfs on the Basis of Optical Spectroscopy". The Astrophysical Journal. 600 (1): 404–408. arXiv:astro-ph/0309483. Bibcode:2004ApJ...600..404B. doi:10.1086/379808. S2CID 16636294.

- ^ "V* V361 Aur". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 2025-08-17.

- ^ Dolez, N.; Vauclair, G.; Chevreton, M. (May 1983). "Identification of gravity modes in the newly discovered ZZ Ceti variable GD 66". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 121: L23 – L26. Bibcode:1983A&A...121L..23D.

- ^ Kholopov, P. N.; Samus, N. N.; Kazarovets, E. V.; Perova, N. B. (March 1985). "The 67th Name-List of Variable Stars". Information Bulletin on Variable Stars. 2681. Bibcode:1985IBVS.2681....1K.

- ^ Hermes, James J. (2013). Complications to the Planetary Hypothesis for GD 66. AAS Meeting #221. American Astronomical Society. Bibcode:2013AAS...22142404H.

- ^ Hermes, J. J. (2012). 8 Years On: A Search for Planets Around Isolated White Dwarfs (PDF). Planets around Stellar Remnants. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-12-27.

External links

- V361 Aurigae Catalog

- WD 0517+307 Catalog

- Image GD 66