Frederick Gilmer Bonfils

Frederick Gilmer Bonfils | |

|---|---|

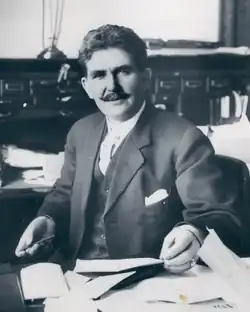

.jpg) 1924 portrait of Bonfils by Harris & Ewing | |

| Born | December 31, 1860 Troy, Missouri, US |

| Died | February 2, 1933 (aged 72) Denver, Colorado, US |

| Resting place | Fairmount Mausoleum, Denver, Colorado, US |

| Occupation(s) | Businessman, publisher |

| Children | Helen and May |

Frederick Gilmer "Bon"[1] Bonfils (December 31, 1860 – February 2, 1933) was an American businessman and publisher who, alongside Harry Heye Tammen, co-owned The Denver Post. He was an early user of yellow journalism.

Early life

Bonfils was born on December 31, 1860, in Troy, Missouri, the second of eight children to lawyer and judge Eugene Napoleon Bonfils and Henrietta B. Lewis. Mayflower crew member John Alden was his 11th-great-grandfather.[1] In 1878, Bonfils entered the United States Military Academy, quitting in 1881 and finding work at the Chemical Bank for some time. In 1882, he married Belle Barton. They moved to Cañon City, Colorado, where Bonfils worked as a drill instructor for a military school. He returned to Missouri to work in insurance, then land development.[1]

Journalism

In 1895, Bonfils moved to Denver.[1] He met Harry Heye Tammen at the Windsor Hotel, where Tammen worked as a bartender. Tammen was also an editor of the Great-Divide Weekly Newspaper and an inauthentic skookum doll seller.[2] Together, on October 28, 1895, they purchased The Denver Post—at the time called the Evening Post—for $12,500.[1][2] They used yellow journalism to reach audiences; it made The Denver Post—which struggled financially before they bought it—the most profitable and most read newspaper in Denver.[3] They justified their style of sensationalistic journalism with the quote "a dogfight on a Denver street is more important than a war in Europe".[4] In their articles, they supported progressive views such as labor reform and anti-corruption.[1]

In December 1899 or January 1900, Tammen and Bonfils were shot in their office by W. W. Anderson, an attorney representing cannibal Alfred Packer, after they published an article—written by Polly Pry—that had accused Packer of cannibalism.[1] In the assault, Bonfils was shot once in the neck, and Tammen once in the chest. Anderson was tried three times, but never convicted. Though, Tammen and Bonfils were convicted for jury tampering in the third trial.[1]

In 1902, Bonfils and Tammen bought the Sells Brothers Circus from Willie Sells and his brothers. Tammen rebranded the show to the Sells Floto Circus, after Otto Floto, the sportswriter of The Denver Post, who was involved in publicity work for the circus.[1] Despite removing Sells and his brothers from the circus, Tammen continued using their likeness to sell it, which stopped in 1909, following a lawsuit by the Sells brothers.[1]

In 1907, Thomas M. Patterson, publisher of the rival Rocky Mountain News, accused Bonfils of blackmail, which he responded to by assaulting Patterson.[1][3] He pursued a lawsuit against the newspaper for the remainder of his life.[5]

In October 29, 1909, Bonfils and Tammen bought the Kansas City Post, and owned it until selling it to Walter S. Dickey on May 18, 1922, for $250,000. Dickey also owned the competing The Kansas City Journal.[1][6]

Despite his anti-corruption reporting, in summer 1922, Bonfils accepted a bribe from oilman Harry Ford Sinclair, worth $250,000—with an offer of $750,000 more—to not report on the Teapot Dome scandal. For this, a United States Senate hearing in 1924 suspended Bonfils from operating The Denver Post.[1]

Bonfils also operated a lottery, which was prized at $800,000 at one point.[5]

Death and legacy

In February 1933, Bonfils had become bed-ridden in his Denver home due to an ear infection, and within the following days, he was encased in an oxygen tent. A baptist visited his house on February 1 and baptized him in bed. He died on February 2, aged 72, of encephalitis[5] and pneumonia, and was interred in the Fairmount Mausoleum at Fairmount Cemetery, Denver.[1] His daughter, Helen inherited, $14,000,000 from him—plus another $10,000,000 from Bonfils' wife, Belle Barton.[7]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n American Council of Learned Societies (1943). Dictionary of American biography. University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. New York, C. Scribner's Sons. pp. 93–96, 1102.

- ^ a b Leavitt, Craig; Noel, Thomas J. (February 15, 2016). Herndon Davis: Painting Colorado History, 1901–1962. University Press of Colorado. ISBN 978-1-60732-420-1.

- ^ a b Abbott, Carl; Leonard, Stephen J.; Noel, Thomas J. (June 15, 2013). Colorado: A History of the Centennial State, Fifth Edition. University Press of Colorado. p. 469. ISBN 978-1-60732-227-6.

- ^ The Continuing Task of Updating America. Time Inc. March 29, 1954. p. 15.

- ^ a b c TIME (February 13, 1933). "Death in Denver". TIME. Retrieved August 8, 2025.

- ^ "Kansas City Post in New Hands. (Published 1922)". May 19, 1922. Retrieved August 8, 2025.

- ^ Varnell, Jeanne (1999). Women of Consequence: The Colorado Women's Hall of Fame. Big Earth Publishing. p. 97. ISBN 978-1-55566-214-1.