Kingdom of the Burgundians

Kingdom of the Burgundians | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 411–534 | |||||||||

The First Kingdom of the Burgundians, after the settlement in Eastern Gaul from 443 | |||||||||

| Capital |

| ||||||||

| Common languages |

| ||||||||

| Religion |

| ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| King | |||||||||

• 411–437 | Gunther | ||||||||

• 532–534 | Godomar | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

| 411 | |||||||||

| 534 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

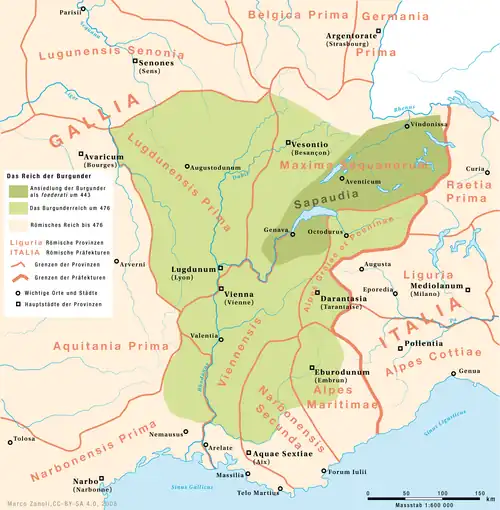

The Kingdom of the Burgundians, or First Kingdom of Burgundy,[2] was a barbarian kingdom in the fifth and sixth centuries, in what is now western Switzerland and south-eastern France. It was ruled by Burgundian kings who were successors of the older Gibichung dynasty, but also held office as Roman military officers. In 451 the Burgundians helped the Roman-led allies defeat Attila the Hun at the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains, and in 455 they helped Roman-mandated forces led by Theodoric II, king of the Visigothic Kingdom, to defeat the Kingdom of the Suevi. After this, the Burgundians were able to expand their territories and their role in the Roman empire, and they moved their capital from Geneva to Lyon. In 534 the rule of the Burgundian kings ended, and the kingdom became part of the Frankish empire.

The kingdom grew out of the 443 Roman resettlement of allied Burgundians to the region of Sapaudia, which at that time included Lake Geneva. These Burgundians were built around the remnants of a previous Roman-allied Burgundian kingdom which the Romans had allowed to settle on the western bank of their Rhine border, probably near Worms, having previously been Roman allies living east of the Rhine, outside the empire. The tribal ruler who was responsible for this move was Gundahar. In about 436, Gundahar and many of the people he led were killed by the Roman military leader Flavius Aetius working with his Hun allies.

Background

The Burgundians who were settled near Lake Geneva saw themselves as a continuation of the Burgundians led by Gundahar who lived west of the Rhine after about 406, and were slaughtered by the Romans and Huns in 436. The legal code made for the kingdom of the Burgundians by King Gundobad (died 516), mentions his royal predecessors (auctores) as not only his father (Gundioc) and paternal uncle (Chilperic I), but also Gibica, Gundomar, Gislahar, and Gundahar.[3] As apparent descendants (or at least successors) of Gibica, this line of kings are referred to today as the Gibichung dynasty, a name which is drawn from medieval heroic legends, including the Niebelungenlied and the Völsunga saga, which depict the memorable defeat of Gundahar by the Huns in highly fictionalized forms.

The Burgundians of Gundahar crossed the Rhine into Roman Gaul before 409, during a period of crisis on the Roman Rhine border region. They were swept along by massive movements of armed Alans, Vandals and other peoples from the east, and conflicts within the Roman empire itself after the death of emperor Theodosius I in 395, when his two sons were still young. Once his younger son Honorius regained centralized Roman control of the Rhine region from the usurper Jovinus in 413, Gundahar's Burgundians were accepted as Roman foederati - non-Romans living within Roman as allies with military obligations. The exact position of this Rhine kingdom is uncertain, but it is this period of Burgundian history which is fictionalised in the Niebelungenlied, which portrays king Gundahar ruling from Worms, south of Mainz, and so this is traditionally seen as the region where they settled.[4]

Before this, the Burgundians lived east of the Rhine, near the Main river. They became particularly important as Roman allies against their neighbours the Alemanni during the reign of Emperor Valentinian I in 364-375. Roman historians Ammianus Marcellinus and Orosius both noted that their forces were large, and also that they believed themselves to be descendants of people who once defended Roman border fortifications near the Main which the Romans had since lost control of. While it is likely that the Romans encouraged this belief themselves, the reports make it unlikely that the Burgundians had any other clear conception of their origins.[5]

In fact the Burgundians near the Main probably at least partly came from what is now Poland. They were first named in surviving written records by Pliny the Elder in the first century, who only mentioned that within the Germanic peoples, the Burgundians were one of the Vandilic group which also included the Varini and Gutones. From other sources however, we know that the Varini, Gutones, and later peoples referred to as Vandals lived east of the Elbe river, quite far from Roman territories. Similarly, in the second century Claudius Ptolemy described Burgundi west of the Vistula river and Phrugundiones east of it, and both of these people might reflect the same people mentioned earlier by Pliny. In the early third century, sixth-century writer Jordanes reported that the Burgundians were devastated in a defeat by the Gepid king Fastida, who was at this time living near the mouth of the Vistula, and looking to expand his territories. A panegyric made in 291 mentions a second devastating defeat in the third century, this time against the eastern European Goths. It was also during the third century that Burgundians first appeared in Roman records regarding conflicts near the Rhine, in what is now Southern Germany.

History

Roman military settlement

The only source to date the Burgundian settlement near Lake Geneva is the unreliable Gallic Chronicle of 452, which records that in 443 “Sapaudia was given to the remainders of the Burgundians to be divided with the indigenous inhabitants.” Its exact boundaries are uncertain, but it lay in the Roman province of Maxima Sequania and included Geneva, and Neuchâtel.[6]

Historian Ian N. Wood notes that this first settlement didn’t draw much attention from contemporaries and probably didn’t involve a large migration of Burgundians.[7] According to him the Burgundians settled in Sapaudia can be seen as a Roman military unit.[8] The first kings were most importantly military officials of the Roman empire.[9] Their non-Roman followers were not all Burgundian, and non-Burgundians joined over time.[10] In Wood’s opinion, a true Burgundian “kingdom” which was not based upon a Roman military office only emerged between 474 and 494.[11] After the accession of Julius Nepos in 474 King Gundobad could no longer claim to represent the western imperial court.[12],

The Lex Burgundionum law code, issued under Gundobad, nonetheless invokes earlier kings back to Gundahar, and beyond. One clause confirms the freedom of persons proved to have been freeborn under earlier “predecessors of royal memory” including not only his father and uncle (Gundioc and Chilperic) but also “Gibica, Gundomar, Gislahar, and Gundahar”.[13] Another clause voids all unresolved Burgundian legal cases before the Battle of the Mauriac Plains (Catalaunian Plains) in 451.[14]

Whether or not Gundioc was the son, or even descendant, of Gundahar, is not certain.[15] Gregory of Tours reported that Gundioc ("Gundevech") was a descendant of the Tervingian Goth Athanaric.[16]

Battle of the Catalaunian Plains

The 451 Battle of the Catalaunian Plains was a decisive turning point for the Burgundians, comparable to its impact on the Visigoths.[17] The Lex Burgundionum, made later, during the time of Gundobad, voids all unresolved Burgundian legal cases prior to the battle.[18]

Burgundians and other barbarian kingdoms from Gaul fought for Rome under Aetius, put Attila the Hun and his allies to flight, but the Visigothic king Theodoric I was killed during the battle, and Thorismund his son followed the advice of Aetius not to pursue.[19] Near contemporary Sidonius Apollinaris reported that Burgundians also fought on the Hun side, who may have lived east of the Rhine outside Roman control.[20]

Imperial politics

Around the time of the battle — “or probably slightly earlier” — Gundioc cemented ties with the future western power-broker Ricimer by marrying his sister, a link that helps explain later Burgundian–imperial coordination.[21]

Attila died in 453, and Aetius in 454, as well as emperor Valentinian III who assassinated him. Also in 454, the Continuatio Prosperi Havniensis surprsingly reports that Burgundians scattered throughout Gaul (intra Galliam diffusi) were driven back (repelluntur) by the Gepids. The Gepids has been one of the most important peoples allied with Attila in his attack on Gaul, but their kingdom was based far away in the area of what is now Romania, so modern scholars suspect either an error in the text, or missing information needed to interpret it properly.[22]

Petronius Maximus was killed in 455 after less than three months in power, and soon afterwards Rome was sacked by the Vandals based in North Africa. On 9 July 455 Theodoric II, the new king of the Visigoths, acclaimed the Gallo-Roman noble Avitus as the new emperor, who was at the Visigothic city of Toulouse at the time, sent by Petronius on an embassy to the Visigoths. In a poem dedicated to Avitus, referring to the time of the sacking, Sidonius implicates an unnamed Burgundian for leading Avitus to be angry at Petronius about the sack.[23]

In 456 the Burgundian kings Gundioc and Chilperic Burgundzonum quoque Gnudiuchum et Hilpericum reges joined Theoderic II on a successful Roman-backed campaign against the Kingdom of the Suebi in Hispania. This is the first time that any of the royal family in Sapaudia are mentioned by name in contemporary records.[24]

However, in October 456 Avitus was overthrown as emperor by Majorian and Ricimer, who became the new emperor and magister militum. Soon after this in 456, Marius Aventicensis reported that the Burgundians "occupied part of Gaul and divided the lands with the Gallic senators".[25] This may have been based on military agreements already made by Avitus, implied by the Burgundian participation in the Suebian campaign. It is also possible that the Gallo-Roman nobility (the senators) didn't accept the new regime in Rome.[26] The military aspect of the new arrangement is apparently reflected in 457, when the Burgundian soldiers return from Hispania, and some may have now been garrisoned in Lyon. The Continuatio Prosperi Havniensis reported that "Gundioc, king of the Burgundians, with his people and all his forces, entered Gaul to settle", with Gothic approval and friendship.[27] According to Wood: "for the first time a formative role in his people’s development is attributed to a member of the Gibichung family".[28]

In 458 Marjorian invaded Gaul without Ricimer, pushing Theoderic II out of Septimania, and occupied the discontented city of Lyon, apparently apparently Burgundian forces from the city. He was murdered by Ricimer in 461. After this, political leadership in the western empire was dominated by the patrician Ricimer, brother-in-law of Gundioc.[29] Under Ricimer’s influence, Burgundian control expanded steadily down the Rhône valley. Lyon was taken from imperial control during the later 460s, and the Burgundians also pushed south towards the Drôme. By this point, Gundioc was recognised not only as king but also as magister militum for Gaul, holding formal Roman military authority.[30]

In 468, the praetorian prefect of Gaul, Arvandus, notoriously suggested to the Visigothic king Euric that Gaul be divided between Goths and Burgundians — a proposal that modern historians generally see as reflecting the strength of these two federate kingdoms relative to the Italian government.[31]

Gundioc died around 470, succeeded by his brother Chilperic I.[31] When Visigothic forces moved up the lower Rhône in 471, Chilperic repelled them, beginning a period of intermittent Burgundian–Gothic hostility. Fighting also continued on the northern frontier: by the mid-470s Burgundians were active against the Alemanni in the Langres–Besançon–Jura region, eventually incorporating much of Maxima Sequanorum and parts of Lugdunensis I into their sphere.[32]

In 472, Ricimer–who was by now the son-in-law of the new Western Emperor Anthemius–was plotting with Gundobad to kill his father-in-law; Gundobad beheaded the emperor (apparently personally).[33] Ricimer then appointed Olybrius; both died, surprisingly of natural causes, within a few months. Gundobad seems then to have succeeded his uncle as Patrician and king-maker, and raised Glycerius to the throne.[34]

In 474, Burgundian influence over the empire seems to have ended. Glycerius was deposed in favour of Julius Nepos, and Gundobad returned to Burgundy. At this time or shortly afterwards, the Burgundian kingdom was divided among Gundobad and his brothers, Godigisel, Chilperic II, and Gundomar I.[35]

Independent kingdom

Chilperic I still held the Roman office of magister militum in Gaul when Gundobad returned from Italy in the mid-470s.Wood 2021, pp. 126–128 Gundobad may have based himself initially at Geneva rather than Lyon, perhaps for strategic reasons given Alpine deployments of the emperor in Italy, Julius Nepos.[36] Gregory of Tours later claimed that Gundobad killed his uncle, but the evidence is ambiguous.[37] By about 480 Chilperic was dead, and Gundobad became the principal king. In Burgundian fashion he shared power with three brothers: Godegisel at Geneva, Chilperic II at Vienne, Isère, and Godomar I at Valence, Drôme.[38]

In 500 Godegisel allied with the Frankish king Clovis I—who had married his niece Clotilde—and turned on Gundobad during a battle near Dijon. Gundobad was defeated and retreated to Avignon. Clovis withdrew, leaving Frankish troops to protect Godegisel in Vienne; with Visigothic help, however, Gundobad retook the city in 501, killing his brother and the Frankish garrison.[39]

After this civil war, Gundobad rebuilt relations with Clovis, united the kingdom under his sole rule, were allies of the Franks during their 507 Battle of Vouillé campaign against the Visigoths.[40] After the Visigothic defeat the Burgundians took Gothic territory in Provence and raided as far as Toulouse and Barcelona.[41] Ostrogothic intervention in 508–509 stripped them of conquests in southern Gaul, and a new peace was arranged fixing the Durance as the southern frontier.[42] The Burgundians emerged almost empty-handed, while the Franks and Ostrogoths made substantial gains.[43]

Gundobad died in 516 and was succeeded by his son Sigismund, who had already ruled from Geneva since about 501.[44] Sigismund converted from Arianism to Catholicism, the faith of his mother, before his father died, and cultivated ties with the Catholic episcopate, notably Avitus of Vienne.[45] His foundation of the Abbey of Saint-Maurice d'Agaune in 515 became a central royal cult site.[43] With the last Western emperors now dead, Sigismund, like his father, kept contact with the eastern Emperors in Constantinople. He honored with the Roman dignity of patricius, which his father had held.[46]

Tensions rose with the Arian Visigoths and Ostrogoths who now ruled Italy rose when, after the death of his first wife Ariagne, a daughter of Theoderic the Great, Sigismund executed his own son Sigerich in 522. In 523–524, conflict with the Ostrogoths and the sons of Clovis brought a two-front invasion. Sigismund was captured by the Franks and executed with his family; his brother Godomar II rallied the Burgundians and defeated the Franks at the Battle of Vézeronce in 524.[47]

Godomar’s reign lasted a decade, marked by renewed alliance with the Ostrogoths and the recovery of territory south of the Durance. In 532–534, however, a coordinated Frankish campaign ended in Burgundian defeat near Autun. The kingdom was partitioned among the victors, becoming a Frankish sub-kingdom while retaining a distinct Burgundian identity.[48]

List of kings

Before Sapaudia, a father and three sons (relationships only implied by legendary versions):

- Gebicca, first king in law code. Legend: Gunther's father Gibeche in Waltharius, Gjúki in Völsunga saga and Poetic Edda

- Gundomar I, second king in law code. Legend: Gunther's brother Gernoz in Þiðrekssaga, Guthorm in Völsunga saga and Poetic Edda

- Giselher, third king in law code. Legend: Gunther's brother Gisler in Þiðrekssaga

- Gundaharius (died 436). Fourth king in law code. A central character in legends (Gunther, Gunnar etc.)

After settlement in Sapaudia, two brothers, and their descendants:

- Gundioc (or Gundovech), a descendant of Athanaric (died about 470)

- Chilperic I of Burgundy, brother of Gundioc (died by 480)

Division of the kingdom among the four sons of Gundioc:

- Gundobad (died 516, king of all of Burgundy from 480)

- Chilperic II? Existence uncertain (possibly killed by Gundobad, possibly the father of Clothilde.[49] Presumably based in Vienne or Valence)

- Gundomar/Godomar (fate uncertain, as with Chilperic II; presumably based in Valence or Vienne)

- Godegisel (killed by Gundobad in 500 in Vienne, based in Geneva)

The line of Gundobad:

- Sigismund, son of Gundobad (died 524)

- Godomar II or Gundimar, son of Gundobad (died 532)

References

- ^ Hallam, Henry (1871). View of the State of Europe During the Middle Ages by Henry Hallam, Incorporating in the Text Authorʼs Latest Researches, with Addidions from Recent Writers, and Adapted to the Use of Students. J. Murray. p. 63.

- ^ (Latin: Regnum Burgundionum) (Latin: Primum Regnum Burgundiae)

- ^ Wood 2003, p. 248 citing Lex Bugundorum, III

- ^ Schipp 2012, Anton 1981, p. 239 citing Prosper, Epitoma Chronicon, under the year 413

- ^ Anton 1981, p. 238, citing Ammianus 28.5, Orosius 7.32

- ^ Wood 2021, pp. 115–116, Wood 2003, p. 246, Anton 1981, p. 241

- ^ Wood 2021, p. 115.

- ^ Wood 2003, p. 262.

- ^ Wood 2021, pp. 120–122.

- ^ Wood 1990, pp. 61–62, Wood 2003, pp. 260–261, Wood 2021, pp. 111–113, 133

- ^ Wood 2016, pp. 250–253.

- ^ Wood 2021, p. 127.

- ^ Lex Burgundionum III

- ^ Lex Burgundionum XVII

- ^ Anton 1981, p. 241, Wolfram 1995

- ^ Wood 2021, p. 113 citing Gregory of Tours, II.28

- ^ Wood 2003, pp. 248–249, Wood 2021, pp. 115–116

- ^ Lex Burgundionum XVII

- ^ Jordanes

- ^ Wood 2021, p. 115 citing Sidonius, Poems, VII

- ^ Wood 2021, p. 116.

- ^ Wood & 2003 253 citing Continuatio Prosperi Havniensis p.304 in MGH edition. In this same period, 454/5, the main Gepid kingdom was part of the winning side at the Battle of Nedao, probably near Slovakia, which was fought among the main allies of Attila after his death.

- ^ Sidonius, Poems, VII, line 442

- ^ Wood 2021, p. 117 citing Jordanes, Getica, 231

- ^ Mathisen 1979, pp. 605–606, Wood 2003, p. 250, Wood 2021, p. 118

- ^ Mathisen 1979, pp. 605–606.

- ^ Mathisen 1979, pp. 605–606, Wood 2021, pp. 117–118 citing Continuatio Prosperi Havniensis p.305 in MGH edition.

- ^ Wood 2003, p. 250

- ^ Wolfram 1995, Wood 2021

- ^ Wolfram 1995, Anton 1981

- ^ a b Wolfram 1995.

- ^ Wolfram 1995, Anton 1981

- ^ Chronica Gallica 511; John of Antioch, fr. 209; Jordanes, Getica, 239

- ^ Marius of Avenches; John of Antioch, fr. 209

- ^ Gregory, II, 28

- ^ Wood 2021, pp. 128–129.

- ^ Wood 2021, p. 128.

- ^ Wolfram 1995, para. 19.

- ^ Wolfram 1995, paras 27-29, Wood 2021, pp. 134–135, Anton 1981, pp. 243–244

- ^ Wolfram 1995, para. 31.

- ^ Halsall 1995, p. 302.

- ^ Wolfram 1995, para. 31, Anton 1981, p. 244

- ^ a b Anton 1981, p. 244.

- ^ Wolfram 1995, para. 33, Anton 1981, p. 244

- ^ Wolfram 1995, para. 34.

- ^ Anton 1981, p. 245.

- ^ Anton 1981, pp. 244–245, Wolfram 1995, paras 36-38

- ^ Wolfram 1995, paras 38-39, Anton 1981, p. 425-426

- ^ Wood 2021, p. 128: "It is possible that there was only one Chilperic, the brother of Gundioc, and that he was the father of Chrotechildis. In which case, he probably was killed by Gundobad. There is, however, not enough evidence to be certain." Wolfram 1995, para. 22: "En 490, il y a de fortes probabilités pour que Godomar comme Hilpéric II, le père de Clotilde, la future épouse de Clovis, soient décédés d’une mort naturelle. "

Sources

- Anton, Hans (1981), "Burgunden II. Historisches § 4-7", in Beck, Heinrich; Geuenich, Dieter; Steuer, Heiko (eds.), Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde, vol. 4 (2 ed.), De Gruyter, pp. 235–248, ISBN 978-3-11-006513-8

- Bury, J.B. The Invasion of Europe by the Barbarians. London: Macmillan and Co., 1928.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Dalton, O.M. The History of the Franks, by Gregory of Tours. Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1927.

- Drew, Katherine Fischer. The Burgundian Code. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1972.

- Gordon, C.D. The Age of Attila. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1961.

- Guichard, Rene, Essai sur l'histoire du peuple burgonde, de Bornholm (Burgundarholm) vers la Bourgogne et les Bourguignons, 1965, published by A. et J. Picard et Cie.

- Halsall, Guy (2007). Barbarian Migrations and the Roman West, 376–568. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52143-543-7. Archived from the original on 23 April 2023. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- Mathisen, Ralph W. (1979), "Resistance and Reconciliation: Majorian and the Gallic Aristocracy after the Fall of Avitus", Francia, 7: 597–628

- Murray, Alexander Callander. From Roman to Merovingian Gaul. Broadview Press, 2000.

- Musset, Lucien. The Germanic Invasions: The Making of Europe AD 400-600. University Park, Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1975.

- Nerman, Birger. Det svenska rikets uppkomst. Generalstabens litagrafiska anstalt: Stockholm. 1925.

- Rivers, Theodore John. Laws of the Salian and Ripuarian Franks. New York: AMS Press, 1986.

- Rolfe, J.C., trans, Ammianus Marcellinus. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1950.

- Shanzer, Danuta. ‘Dating the Baptism of Clovis.’ In Early Medieval Europe, volume 7, pages 29–57. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers Ltd, 1998.

- Shanzer, D. and I. Wood. Avitus of Vienne: Letters and Selected Prose. Translated with an Introduction and Notes. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2002.

- Werner, J. (1953). "Beiträge zur Archäologie des Attila-Reiches", Die Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaft. Abhandlungen. N.F. XXXVIII A Philosophische-philologische und historische Klasse. Münche

- Wolfram, Herwig (1997). The Roman Empire and Its Germanic Peoples. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520085114. Archived from the original on 2023-04-23. Retrieved 2020-01-26.

- Wolfram, Herwig (1995), "Les Burgondes : faiblesse et pérennité (407/413-534)", in Gaillard de Sémainville, Henri (ed.), Les Burgondes, translated by Raviot, Jacques, ARTEHIS Éditions, doi:10.4000/books.artehis.17631

- Wood, Ian N. (1990), "Ethnicity and the Ethnogenesis of the Burgundians", in Wolfram, Herwig; Pohl, Walter (eds.), Typen der Ethnogenese unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Bayern, vol. 1, Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, pp. 53–69

- Wood, Ian N. The Merovingian Kingdoms. Harlow, England: The Longman Group, 1994.

- Wood, Ian N. (2003), "Gentes, Kings and Kingdoms—The Emergence of States: The Kingdom of the Gibichungs", Regna and Gentes, Brill, doi:10.1163/9789047404255_012

- Wood, Ian N. (2021), "The Making of the 'Burgundian Kingdom", Reti Medievali Journal, 22 (2): 111–140, doi:10.6093/1593-2214/7721, ISSN 1593-2214