Eugeneodontiformes

| Eugeneodontiformes Temporal range: Early Carboniferous (Serpukhovian) to Early Triassic (Olenekian)

| |

|---|---|

| |

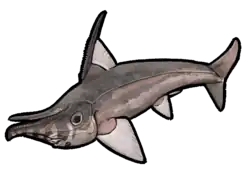

| Helicoprion davisii | |

| |

| Edestus heinrichi | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Order: | † Zangerl, 1981 |

| Families | |

|

See text | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

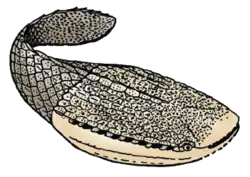

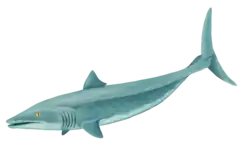

The Eugeneodontiformes, (also called Eugeneodontida) is an extinct and poorly known order of cartilaginous fishes. They possessed "tooth-whorls" on the symphysis of either the lower or both jaws and pectoral fins supported by long radials. They probably lacked pelvic fins and anal fins.[1] The palatoquadrate was either fused to the skull or reduced. Now determined to be within the Holocephali, their closest living relatives are chimaeras.[2] The eugeneodonts are named after paleontologist Eugene S. Richardson, Jr.[3] The group first appeared in the fossil record during the late Mississippian (Serpukhovian).[4] The youngest eugeneodonts are known from the Early Triassic.[5] The geologically youngest fossils of the group are known from the Sulphur Mountain Formation (western Canada), Vardebukta Formation (Svalbard, Norway) and Wordie Creek Formation (Greenland).

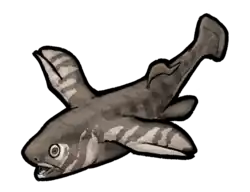

Members of the Eugeneodontiformes are further classified into two superfamilies and either four or five different families. The Helicoprionidae and Edestidae are assigned to the superfamily Edestoidea, the former containing genera such as Helicoprion, Sarcoprion, and Parahelicoprion, and the latter containing the genera such as Edestus and Lestrodus. The family Helicampodontidae has been used for genera that do not closely resemble typical members of either of these two groups.[6] The superfamily Eugeneodontoidei (traditionally Caseodontoidea)[7] includes the families Caseodontidae and Eugeneodontidae, which were smaller and less-specialized than the edestoids.[3] Eugeneodonts were predatory, with eugeneodontoids likely being generalist feeders and some edestoids being specialized for hunting cephalopods.[1][3][8]

Among the eugeneodonts, some members of the superfamily Edestoidea are probably the largest marine animals of their time, with the Late Carboniferous Edestus estimated to reach about or exceeding 6.7 metres (22 ft) in length,[9][10] with some Early Permian Helicoprion suggested to be over 7.6 metres (25 ft) long by some estimates (though the body length estimates for both genera are somewhat speculative due to both only being known from skull material).[9][10][8]

Taxonomy

The list below shows taxa included within Eugeneodontida.[11]

- Superfamily Caseodontoidea

- Family Caseodontidae

- Genus Caseodus

- Genus Erikodus

- Genus Fadenia

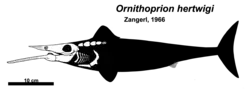

- Genus Ornithoprion

- Genus Pirodus

- Genus Romerodus

- Family Eugeneodontidae

- Genus Bobbodus

- Genus Eugeneodus

- Genus Gilliodus

- Family incertae sedis

- Genus Campodus

- Genus Chiastodus

- Genus Tiaraju

- Family Caseodontidae

- Superfamily Edestoidea

- Family Edestidae

- Family Helicampodontidae

- Genus Helicampodus

- Genus Hunanohelicoprion

- Genus Parahelicampodus

- Genus Sinohelicoprion

- Family Helicoprionidae

- Genus Agassizodus

- Genus Arpagodus

- Genus Campyloprion

- Genus Helicoprion

- Genus Parahelicoprion

- Genus Sarcoprion

- Genus Toxoprion

- Family incertae sedis

- Genus Paredestus

References

- ^ a b Lebedev, O.A. (2009). "A new specimen of Helicoprion Karpinsky, 1899 from Kazakhstanian Cisurals and a new reconstruction of its tooth whorl position and function". Acta Zoologica. 90: 171–182. doi:10.1111/j.1463-6395.2008.00353.x. ISSN 0001-7272.

- ^ Tapanila L.; Pruitt J.; Pradel A.; Wilga C.; Ramsay J.; Schlader R.; Didier D. (2013). "Jaws for a spiral-tooth whorl: CT images reveal novel adaptation and phylogeny in fossil Helicoprion". Biology Letters. 9 (2): 20130057. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2013.0057. PMC 3639784. PMID 23445952.

- ^ a b c Zangerl, R. (1981). Handbook of Paleoichthyology. Volume 3A. Chondrichthyes I. Paleozoic Elasmobranchi. Stuttgart: Gustav Fischer Verlag. ISBN 978-3-89937-045-4.

- ^ Hodnett, John-Paul M.; Elliott, David K. (December 2018). "Carboniferous chondrichthyan assemblages from the Surprise Canyon and Watahomigi formations (latest Mississippian–Early Pennsylvanian) of the western Grand Canyon, Northern Arizona". Journal of Paleontology. 92 (S77): 1–33. doi:10.1017/jpa.2018.72. ISSN 0022-3360.

- ^ Scheyer, Torsten M.; Romano, Carlo; Jenks, Jim; Bucher, Hugo (19 March 2014). "Early Triassic Marine Biotic Recovery: The Predators' Perspective". PLOS ONE. 9 (3): e88987. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...988987S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0088987. PMC 3960099. PMID 24647136.

- ^ Lebedev, O. A.; Itano, W. M.; Johanson, Z.; Alekseev, A. S.; Smith, M. M.; Ivanov, A. V.; Novikov, I. V. (2022). "Tooth whorl structure, growth and function in a helicoprionid chondrichthyan Karpinskiprion (nom. nov.) (Eugeneodontiformes) with a revision of the family composition". Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. 113 (4): 337–360. doi:10.1017/S1755691022000251.

- ^ Van der Laan, Richard (2018-10-11). "Family-group names of fossil fishes". European Journal of Taxonomy (466). doi:10.5852/ejt.2018.466. ISSN 2118-9773.

- ^ a b Tapanila, Leif; Pruitt, Jesse; Wilga, Cheryl D.; Pradel, Alan (2020). "Saws, Scissors, and Sharks: Late Paleozoic Experimentation with Symphyseal Dentition". The Anatomical Record. 303 (2): 363–376. doi:10.1002/ar.24046. ISSN 1932-8494. PMID 30536888.

- ^ a b Tapanila, Leif; Pruitt, Jesse (2019-09-04). "Redefining species concepts for the Pennsylvanian scissor tooth shark, Edestus". PLOS ONE. 14 (9): e0220958. Bibcode:2019PLoSO..1420958T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0220958. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 6726245. PMID 31483800.

- ^ a b Engelman, Russell K. (2023). "A Devonian Fish Tale: A New Method of Body Length Estimation Suggests Much Smaller Sizes for Dunkleosteus terrelli (Placodermi: Arthrodira)". Diversity. 15 (3): 318. doi:10.3390/d15030318. ISSN 1424-2818.

- ^ Ginter, M.; Hampe, O.; Duffin, C. (2010). Handbook of Paleoichthyology. Volume 3D. Chondrichthyes. Paleozoic Elasmobranchi: Teeth. Munich: Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil. ISBN 978-3-89937-116-1.

External links

- [1] Palaeos Vertebrates 70.100 Chondrichthyes: Eugnathostomata at paleos.com

- JSTOR: Journal of Paleontology Vol. 70, No. 1 (Jan., 1996), pp. 162–165

- More about Chondrichthyes Archived 2017-10-22 at the Wayback Machine at Devonian Times