Elizabeth Gunning (writer)

Elizabeth Gunning | |

|---|---|

.jpg) 1796 portrait | |

| Born | 13 June 1769 Edinburgh, Scotland |

| Died | 20 July 1823 (aged 54) Long Melford, Suffolk, England |

| Other names | Mrs. Plunkett |

| Occupation(s) | Novelist and translator |

| Spouse |

James Plunkett (m. 1803) |

| Parent(s) | Susannah Gunning and John Gunning |

Elizabeth Gunning (13 June 1769 – 20 July 1823) was an English novelist and translator of French, who also published under her married name Elizabeth Plunkett.

In the 1790s, Gunning was the subject of a pamphlet war related to a rumoured relationship with Lord Blandford. She and her mother were accused of forging a series of letters, purportedly by Blandford and his father the duke of Marlborough, which were published as evidence that Blandford had proposed marriage to Gunning. Gunning was ejected from her father's household, and briefly moved to France with her mother to avoid repercussions from the scandal.

Afterward, Gunning followed in the footsteps of her mother, the novelist Susannah Gunning, with a prolific writing career. She published thirteen works of fiction and six translations between 1794 and 1815. Her first two works were novels of sensibility, after which she also wrote Gothic novels and books for children. Gunning married James Plunkett, an Irish military officer, in 1803 and had four sons. She continued publishing with both "Mrs. Plunkett" and "Miss Gunning" on the title page of her works. She died in 1823.

Early life and family

Born in 1769 in Edinburgh, Gunning was the only child of the writer Susannah Gunning and the military officer John Gunning.[1][2] Her paternal grandparents were impoverished Irish aristocrats: John Gunning of Castle Coote in County Roscommon and Bridget Bourke, daughter of Theobald Bourke, the sixth Viscount Mayo.[3] She was born in 1769 in northern Britain, where her father was deputy adjutant general.[1] During the American Revolutionary War her father served abroad; when he returned, the family relocated to Langford Court in Lower Langford, Somerset.[1] In June 1788, they moved to London, renting houses in St James's Place and Twickenham.[1]

Two of Gunning's paternal aunts made surprising marriages to members of the aristocracy: Maria became the countess of Coventry and Elizabeth became duchess first of Hamilton and then of Argyll.[1][4] They were somewhat notorious for their beauty and social climbing.[5] Another aunt, her mother's sister Margaret Minifie, was a novelist.[6]

False engagement scandal

In her early twenties, Gunning became notorious as a failed social climber, who attempted to imitate her aunts' aristocratic marriages through manipulation and forgery.[5] Her apparent targets were her cousin George Campbell, at that time known as the Marquess of Lorne, and George Spencer-Churchill, at that time known as the marquess of Blandford.[1][7] Both Lorne and Blandford were the heirs of Dukes; Lorne was the son of the Duke of Argyll, and Blandford was the son of the Duke of Marlborough.[1] The real events of the scandal are difficult to discern, and several contradictory accounts of Gunning's character and actions were published.[7][8] Early rumours connected Gunning with Lorne; these were superseded by rumours of a flirtation with Blandford in 1790.[1][7] Gunning told her close friends in the autumn of 1790 that she was engaged to Blandford,[7] with the news circulating by August.[9] As early as October 1790, the writer Horace Walpole mocked Gunning in letters to his friends and cast doubt on the engagement.[10]

.jpg)

In February 1791, Gunning's father wrote to Blandford's father out of concern that no wedding date had been set;[7] he received a forged response.[6] The forged letter indicated that Gunning had exchanged love letters with Blandford but ultimately affirmed her romantic attachment to Lorne; it ventriloquized Blandford's father to praise Gunning's virtues and expressed regret that Blandford had squandered his opportunity to marry her.[11] This letter was publicly circulated alongside others purportedly from Blandford and Gunning during their flirtation, then exposed as forgeries.[1][7][8] Gunning's father ejected her and her mother from his household, apparently furious about their scheme.[1] They swore affidavits of innocence and moved in with Blandford's grandmother, the duchess of Bedford, who defended them.[1][7] Gunning's mother published a 147-page pamphlet blaming her husband for trying to pin the capital offense of forgery on his innocent daughter.[12][13] It defended Gunning in a melodramatic style similar to that of her novels,[12] and was reprinted several times due to its popular sales.[14]

Speculation about Gunning was a matter of public discussion for months.[7] London society debated the intent of the forged letters: perhaps they were supposed to threaten Blandford's reputation and pressure him into marriage; perhaps Lorne was the real target, and the letters were meant to prompt a jealous offer of marriage from him; or perhaps ruining Gunning's reputation was the point, and Gunning's father orchestrated the scheme to avoid the cost of supporting his wife and daughter during a time of financial need.[15][15] None of these theories was considered entirely satisfying; The Gentleman's Magazine complained: "[Blandford] could not be drawn into a marriage by a correspondence of which he was ignorant; and it was surely not a very likely means for the young Lady to engage the heart of any other Nobleman [i.e. Lorne], by pretending to be violently enamoured herself of another".[10] The satirist James Gillray produced three caricatures of the Gunnings,[8] and Horace Walpole gave the satirical name the "Gunninghiad" to the whole affair.[6]

As the scheme fell apart, the public also debated which Gunnings were to blame for betraying the trust of their close family: most either blamed Gunning for deceiving both of her parents, or blamed Gunning and her mother for conspiring against her father; those who saw Gunning as innocent instead blamed her father for intentionally ruining his daughter.[16][15] Eventually, responsibility for the act of forgery was claimed by Essex Bowen, a cousin of Gunning's father.[15] He insisted that he produced and delivered the letters on Gunning's orders, though some suspected him of actually colluding with her father.[15] At the time, the final consensus assigned blame to one or both of the Gunning women.[1] Today, historians consider it equally plausible that Gunning's father was responsible, motivated by his growing gambling debts.[1] At the conclusion of the affair, Gunning and her mother temporarily relocated to France to escape the scandal and the risk of prosecution for forgery.[8][6]

Writing

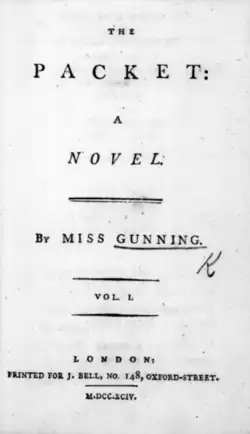

Gunning began her career as an author in 1794, and ultimately published nine novels, six translations from French, and four children's books.[5][17] Her first novel, The Packet (1794), begins with a preface claiming that she was a reluctant amateur pressured into writing due to financial need.[18] The scholar Valerie Derbyshire considers the preface a fundamentally accurate description of Gunning's motivation to write under "[t]he threat of destitution and the shadow of scandal", deprived of her father's financial support.[19] In contrast, literary historian Pam Perkins argues that this self-presentation is a marketing cliché.[20] Perkins describes Gunning as highly professional in her management of her career.[20] Unlike many writers who wrote "on speculation"—completing a manuscript first and then attempting to sell it to a publisher—Gunning secured a contract before beginning to write The Packet.[20] When she wrote more than the contracted four volumes, she removed the extra material to be sold separately as her second book, Lord Fitzhenry.[20]

Especially at the start of her career, Gunning used her notoriety as a marketing tool.[21] The vast majority of novels in this period were published anonymously,[22] but Gunning consistently published with her highly-recognizable name on the title page; even after her marriage, her novels continue to point out that "Mrs. Plunkett" should be known to readers as "Miss Gunning".[20][21] Her early novels also focus on narratives of scandal, and include commentary from the author breaking the fourth wall to defend herself from critics.[21]

Gunning's first two novels were novels of sensibility; her third, The Foresters (1796), was a Gothic novel which falsely claimed to be a translation from the French, using the trope of the found manuscript.[23][5] All of Gunning's works were reprinted and pirated frequently during her life, indicating a successful career as a writer.[5] Perkins says: "Hers was not a dazzling literary career, like Burney's or Smith's, but it was solid and respectable".[18] After her death, however, her works were soon forgotten.[5][24] The literary historian Isobel Grundy's assessment of her ouvre is mixed: "Elizabeth Gunning's early novels are, like her mother's, sentimental, with heavy-footed humour, trite moralizing, a self-consciously elaborate style, and intense class-consciousness. Each woman wrote more interestingly, with more criticism of society, later in life."[1] Gunning's most celebrated French translation was of The Plurality of Worlds by Bernard Le Bovier de Fontenelle, first written in 1686.[5]

Later life and death

Gunning's father died in 1799, and she received a substantial inheritance.[18] Her mother died in 1800.[6] In 1803, Gunning married Major James Plunkett of Kinnaird, County Roscommon.[25][26][1] They had four sons: Coventry Plunkett (born 1805), James Gunning Plunkett (1807–1849), John Gunning Plunkett (born 1808), and George Argyll Plunkett (1811–1902).[27] Their grandson, James Gunning Plunkett, was an army officer with estates in Roscommon.[28]

Gunning died on 20 July 1823, at Long Melford, Suffolk.[1] Her death notice in The Gentleman's Magazine described her as "a lady endowed with many virtues, and considerable accomplishments."[29]

Works

Novels

- The Packet, 4 vols. 12mo, London: Bell, 1794.

- Lord Fitzhenry, 3 vols. 12mo, London: Bell, 1794.

- The Foresters. A Novel, 4 vols. 12mo, London: Low, 1796.

- This is an original novel which claims to be a translation from French.[5]

- The Orphans of Snowdon. A Novel, 3 vols. 12mo, London: Lowndes, 1797.

- The Gipsey Countess. A Novel, 5 vols. 12mo, London: Longman & Rees, 1799.

- Family Stories; or Evenings at my Grandmother's, 2 vols. 12mo, London: Tabart, 1802.

- The Farmer's Boy, 4 vols. 12mo, London: Crosby, Hurst and M. Jones, 1802.

- The Heir Apparent: A Novel. By the Late Mrs Gunning [...] Revised and Augmented by her Daughter, Miss Gunning, 3 vols, London: Ridgway and Symonds, 1802.

- A Sequel to Family Stories, &c., 12mo, London: Tabart, 1802.

- The Village Library; Intended for the Use of Young Persons, 18mo, London: Crosby, 1802.

- The War-Office: A Novel, 3 vols. 12mo, London: printed for the author, 1803.

- The Exile of Erin, 3 vols. 12mo, London: Crosby, 1808.

- The Man of Fashion: A Tale of Modern Times, 2 vols. 12mo, London: M. Jones, 1815.

- Also published with the title The Victims of Seduction; or, Memoirs of a Man of Fashion.[27]

Translations from French

- Memoirs of Madame de Barneveldt. Translated from the French by Miss Gunning, 2 vols. 8vo, London: Low and Booker, 1795.[5]

- Conversations on the Plurality of Worlds by M. de Fontenelle. With Notes, and a Critical Account of the Author's Writings, by Jerome de la Lande [...] Translated from a Late Paris Edition, by Miss Elizabeth Gunning, 12mo, London: Dundee and Hurst, 1803.[5]

- The Wife with Two Husbands: A Tragi-Comedy, in Three Acts. Translated from the French of Pixerécourt, 8vo, London: Symonds, 1803.

- Gunning offered this script and an opera based upon it to Covent Garden and Drury Lane, without success.[5]

- Malvina by Madame C***** [Cottin], Authoress of Clare d'Albe and Amelia Mansfield. Translated from the French by Miss Gunning, 4 vols. 12mo, London: Hurst, Chapple, and Dutton, 1804.[5]

- Dangers through Life; or, The Victim of Seduction. A Novel [...] By Mrs Plunkett (Late Miss Gunning), 3 vols, London: J. Ebers, 1810.

- Gunning presented this loose translation of Claude Joseph Dorat's Les Malheurs de l'inconstance (1772) as her own original work.[17]

- Sentimental Anecdotes, by Madame de Montolieu, Author of 'Tales, 'Caroline of Lichfield: &c. &c. &c. [...] Translated from the French by Mrs Plunkett, Formerly Miss Gunning, 2 vols, London: Chapple, 1811.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Grundy 2004.

- ^ "Author: Gunning, Susannah". Jackson Bibliography of Romantic Poetry. University of Toronto Libraries. Retrieved 16 August 2025.

- ^ Derbyshire 2023, p. xxii.

- ^ Perkins 1996, p. 96.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Derbyshire 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Todd 1985, pp. 258–259.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Perkins 1996, p. 85.

- ^ a b c d Eckert 2022, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Beebee 2007, p. 71.

- ^ a b Perkins 1996, p. 86.

- ^ Beebee 2007, p. 70.

- ^ a b Perkins 1996, pp. 86–87.

- ^ "A letter from Mrs. Gunning, addressed to His Grace the Duke of Argyll". HathiTrust. 1791. hdl:2027/uc1.aa0014245468. Retrieved 6 July 2025.

- ^ Eckert 2022, p. 162.

- ^ a b c d e Perkins 1996, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Beebee 2007, p. 72.

- ^ a b Belanger, Jacqueline; Garside, Peter; Mandal, Anthony; Ragaz, Sharon (20 August 2020). "The English Novel, 1800–1829 & 1830–1836: Update 7 (August 2009–July 2020)". Romantic Textualities. Retrieved 22 July 2025.

- ^ a b c Perkins 1996, p. 83.

- ^ Derbyshire 2023, pp. xi–xii.

- ^ a b c d e Perkins 1996, pp. 94–95.

- ^ a b c Derbyshire 2023, p. xi.

- ^ Raven 2000, p. 41.

- ^ Derbyshire 2023, p. xii, xviii.

- ^ Derbyshire 2023, p. xxi.

- ^ "Marriages". The Gentleman's Magazine. Vol. 94. 1803. p. 1251.

Major Plunkett, to Miss Gunning, authoress of several interesting publications.

- ^ Burke, John (1832). A General and Heraldic Dictionary of the Peerage and Baronetage. Vol. 1.

- ^ a b Derbyshire 2023, p. xxxi-xxxii.

- ^ "Gunning Plunkett | Landed Estates | University of Galway". landedestates.ie. Retrieved 4 August 2025.

- ^ The Gentleman's Magazine, August 1823. Vol. 93. Open Court Publishing Co. 1823. p. 190 – via Internet Archive.

Works cited

- Beebee, Thomas O. (2007). "Publicity, Privacy, and the Power of Fiction in the Gunning Letters". Eighteenth-Century Fiction. 20 (1): 61–88. doi:10.3138/ecf.2007.20.1.61.

- Derbyshire, Valerie Grace, ed. (2023). The Foresters: A Novel. University of Wales Press.

- Derbyshire, Val (2024). "Gunning, Elizabeth". The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Romantic-Era Women's Writing. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. pp. 1–4. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-11945-4_232-1. ISBN 978-3-030-11945-4.

- Eckert, Lindsey (17 June 2022). The Limits of Familiarity: Authorship and Romantic Readers. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-1-68448-390-7.

- Grundy, Isobel (2004). "Gunning [married name Plunkett], Elizabeth (1769–1823)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 24 (Hardcover ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 247-248. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/11745. ISBN 0198613741. (Subscription, Wikipedia Library access or UK public library membership required.)

- Perkins, Pam (1996). "The Fictional Identities of Elizabeth Gunning". Tulsa Studies in Women's Literature. 15 (1): 96. doi:10.2307/463975. ISSN 0732-7730. JSTOR 463975.

- Raven, James (2000). "Historical Introduction: The Novel Comes of Age". The English Novel 1770–1829: A Bibliographical Survey of Prose Fiction Published in the British Isles. Vol. I: 1770–1790. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-818317-4.

- Todd, Janet (1985). "Plunkett, Elizabeth (1769-1823)". A Dictionary of British and American women writers, 1660–1800. Rowman & Allanheld. pp. 258–259.