Edward Heawood

Edward Heawood | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | August 26, 1863 |

| Died | April 30, 1949 (aged 85) |

| Occupation(s) | Librarian, Geographer |

| Known for | Filigranology, History of cartography |

Edward Heawood (26 August 1863–30 Apr 1949) was a British geographer who was librarian to the Royal Geographical Society from 1901 to 1934. He published extensively on the history of discovery and cartography. He is particularly noted for his work on paper and filigranology, the study of watermarks, as a means of dating maps and other documents

Life and work

Heawood was born in Newport, Shropshire. His father was headmaster of Newport School, and later became Rector of Combs, Suffolk. Edward was educated at Queen Elizabeth's Grammar School, Ipswich, and Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge.[1][2] After graduating from Cambridge in 1886, he became a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society and trained in surveying, geology and botany, and then spent two years in the Dooars, south of the Himalayas in Bengal, assisting in establishing a colony of the Santal people.[1][3][4] Returning to England, he joined the staff of the Royal Geographical Society as an assistant, working on the Geographical Journal, which had been recently started, and in the library. In 1901 he became the Society's librarian, a post he held until 1934. During this period he greatly expanded the Library's collections, in particular of early geographical material including early printed atlases and texts.[4][5] As well as expanding and cataloguing the collections, Heawood also supervised two major moves of the library, from Savile Row to Lowther Lodge, and then to the new library opened in 1930.[6] In 1908, He was appointed as the first permanent treasurer of the Hakluyt Society, a post he held for 38 years.[7]

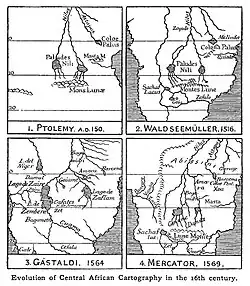

Heawood published extensively on early maps and the history of geographic discovery, and was described by Helen Wallis, Superintendent of the Map Room of the British Library as the "pre-eminent authority" in this field.[8] His most substantial work was A History of Geographical Discovery in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries (1912). In his Preface, Heawood remarks that the period is outside the "Age of Great Discoveries", and that while individual episodes have been described, a connected view of the period was lacking.[9] He increasingly studied the map sources of this and earlier periods. Some of his published accounts are of maps and atlases acquired by the Society, for example the Hondius map of 1608;[10] and some relate to newly discovered maps in other collections, such as the Contarini–Rosselli world map of 1506 acquired by the British Museum in 1922.[11] Gerald Crone, Heawood/s successor as Librarian to the Royal Geographical Society, remarked that "there was scarcely any important contribution to the study [of the history of cartography] that he did not review, critically but fairly, in The Geographical Journal".[1] Heawood was much in favour of the publication of facsimiles of historical maps, and reviewed a number of these productions over the years.[12][13]

In 1907, Briquet published his four-volume work on filigranology, the study of watermarks.[14] Heawood had already been struck by the distinctive forms of watermarks in some of the documents he was working on, and Briquet's work stimulated him to work systematically on this topic, both for the dating of documents and for invesigation into the sources of the paper used in book and map production. Briquet's cataloguing work covered the period up to 1600, and focussed mainly on manuscripts. Heawood, being greatly interested in the 17th- and 18th-centuries, and working largely with printed sources, was thus able to complement Briquet's great work. His first publication in this area, The use of watermarks in dating old maps and documents appeared in 1924 in The Geographical Journal, and established his reputation as a filigranologist.[1] It was reprinted as an appendix to a book on old maps and globes in 1965.[15] The 1924 article was followed by a series of papers in The Library between 1928 and 1948. This research culminated in Watermarks: Mainly of the 17th and 18th Centuries which described and illustrated over 4000 watermarks. The project was made possible by E.J. Labarre, founder of the Paper Publications Society, which published Watermarks in 1950.[1] [16][17]

Heawood died on 30 April 1949, before completing the editing of Watermarks. According to Crone, he was working on indexing marks on the day of his death.[1] Crone and Labarre completed the editing work.[16][17] Heawood was survived by his wife Lucy. They had married in 1895.[1] In 1933 Heawood received the Research Medal of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society, and in 1934 the Victoria Medal of the Royal Geographical Society.[4]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g Crone, G.R. (1950) "Edward Heawood 1863-1949". In: Heawood, E. 1950, Watermarks, Mainly of the 17th and 18th Centuries. Paper Publications Society, pp 17-19

- ^ "Contemporary birthdays". Nature. 118 (1264): 287. 26 August 1926. Bibcode:1926Natur.118Q.287.. doi:10.1038/118287A0.

- ^ "Edward Heawood". ACAD A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge. Retrieved 10 July 2025.

- ^ a b c Crone, G. R. (11 June 1949). "Mr. Edward Heawood" (PDF). Nature. 163 (4154): 901. Bibcode:1949Natur.163..901C. doi:10.1038/163901a0. ISSN 0028-0836. Retrieved 10 July 2025.

- ^ Crone, G. R.; Day, E. E. T. (1960). "The Map Room of the Royal Geographical Society". The Geographical Journal. 126 (1): 12–17. Bibcode:1960GeogJ.126...12C. doi:10.2307/1790424. JSTOR 1790424.

- ^ Crone, G. R. (1955). "The Library of the Royal Geographical Society". The Geographical Journal. 121 (1): 27–32. Bibcode:1955GeogJ.121...27C. doi:10.2307/1791804. JSTOR 1791804.

- ^ Howgego, Raymond John (23 June 2019). "The History of the Hakluyt Society". The Hakluyt Society. Retrieved 14 July 2025.

- ^ Wallis, Helen (1973). "Preface". In Wallis, Helen; Tyacke, Sarah (eds.). My Head Is A Map: Essays and memoirs in honour of R.V. Tooley. Kunstpedia Foundation. ISBN 978-90-816542-1-0. Retrieved 10 July 2025.

- ^ Heawood (1912) p. v

- ^ Heawood (1919)

- ^ Heawood (1923)

- ^ Heawood (1904)

- ^ Heawood (1930a)

- ^ Briquet, Charles-Moïse (1907). Les filigranes (in French). A. Jullien. Volume 1; Volume 2; Volume 3; Volume 4. Second edition (1923, Leipzig: Hiersemann): Volume 1; Volume 2; Volume 3; Volume 4.

- ^ Lister, Raymond (1965). How to Identify Old Maps and Globes: With a List of Cartographers, Engravers, Publishers, and Printers Concerned with Printed Maps and Globes from C. 1500 to C. 1850. Archon Books. Retrieved 13 July 2025.

- ^ a b Stevenson, Allan H. (1951). "A Critical Study of Heawood's" Watermarks Mainly of the 17th and 18th Centuries"". The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America. 45 (1): 23–36. doi:10.1086/pbsa.45.1.24298685.

- ^ a b Hazen, A.T. (1952). "Review of Watermarks Mainly of the 17th and 18th Centuries, by E. Heawood". The Library Quarterly. 22 (1): 51-53. doi:10.1086/617846.

Selected bibliography

- Heawood, Edward (1894). "Dr. Baumann's Journey through East Africa". The Geographical Journal. 4 (3): 246–250. Bibcode:1894GeogJ...4..246H. doi:10.2307/1774238. JSTOR 1774238.

- —— (1896). Geography of Africa. Macmillan & Company.

- —— (1899). "Some New Books on Africa". The Geographical Journal. 13 (4): 412–422. Bibcode:1899GeogJ..13..412H. doi:10.2307/1774831. JSTOR 1774831.

- —— (1899). "Was Australia Discovered in the Sixteenth Century?". The Geographical Journal. 14 (4): 421–426. Bibcode:1899GeogJ..14..421H. doi:10.2307/1774453. JSTOR 1774453.

- —— (1900). "The commercial resources of tropical Africa". Scottish Geographical Magazine. 16 (11): 651-657. doi:10.1080/00369220008733202.

- —— (1904). "The Waldseemüller Facsimiles". The Geographical Journal. 23 (6): 760–770. doi:10.2307/1776494. JSTOR 1776494.

- —— (1909). "Marine World Chart of Nicolo de Canerio Januensis, 1502 (circa)". The English Historical Review. 24 (94): 351–353. doi:10.1093/ehr/XXIV.XCIV.351. JSTOR 549675.

- —— (1909). "Martin Behaim; His Life and His Globe". The English Historical Review. 24 (96): 790–792. doi:10.1093/ehr/XXIV.XCVI.790. JSTOR 550465.

- —— (1909). "Some Cartographical Documents of the Age of Great Discoveries". The Geographical Journal. 33 (6): 679–688. doi:10.2307/1777555. JSTOR 1777555.

- —— (1912). A History of Geographical Discovery in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. Cambridge University Press.

- —— (1919). "Hondius and His Newly-Found Map of 1608". The Geographical Journal. 54 (3): 178–184. Bibcode:1919GeogJ..54..178H. doi:10.2307/1780058. JSTOR 1780058.

- —— (1920). "The Historical Geography of Northern Eurasia". The Geographical Journal. 56 (6): 491–496. Bibcode:1920GeogJ..56..491H. doi:10.2307/1780472. JSTOR 1780472.

- —— (1921). "The world map before and after Magellan's voyage". The Geographical Journal. 57 (6): 431–442. Bibcode:1921GeogJ..57..431H. doi:10.2307/1780791. JSTOR 1780791.

- —— (1923). "A Hitherto Unknown World Map of A. D. 1506". The Geographical Journal. 62 (4): 279–293. Bibcode:1923GeogJ..62..279H. doi:10.2307/1781021. JSTOR 1781021.

- —— (1924). "The Use of Watermarks in Dating Old Maps and Documents". The Geographical Journal. 63 (5): 391–410. Bibcode:1924GeogJ..63..391H. doi:10.2307/1781227. JSTOR 1781227.

- —— (1928). "The position on the sheet of early watermarks". The Library. 4th Series Volume 9: 38–47. doi:10.1093/library/s4-IX.1.38.

- —— (1929). "Sources of early English paper supply". The Library. 4th Series Volume 10 (3): 282–307. doi:10.1093/library/s4-X.3.282.

- —— (1930a). "Reproductions of Notable Early Maps". The Geographical Journal. 76 (3): 240–248. Bibcode:1930GeogJ..76..240H. doi:10.2307/1784798. JSTOR 1784798.

- —— (1930b). "Paper used in England after 1600: I The Seventeenth Century to c. 1680". The Library. 4th Series Volume 11 (3): 263–299. doi:10.1093/library/s4-XI.3.263. ISSN 0024-2160.

- —— (1931). "Paper used in England after 1600: II. c. 1680-1750". The Library. 4th Series Volume 11 (4): 466–498. doi:10.1093/library/s4-XI.4.466. ISSN 0024-2160.

- —— (1947). "Further Notes on Paper used in England after 1600". The Library. 5th Series Volume 2 (2–3): 119–149. doi:10.1093/library/s5-II.2-3.119. ISSN 0024-2160.

- —— (1950). Watermarks, Mainly of the 17th and 18th Centuries. Hilversum: Paper Publications Society.