Edmond Benoît

Edmond Benoît | |

|---|---|

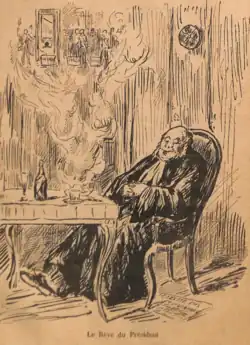

Edmont Benoit's 'The dream of the president' caricature in Le Père Peinard (6 September 1891) | |

| Born | 20 April 1843 |

| Died | 27 June 1909 Paris |

| Era | Ère des attentats - Belle Époque |

| Employer | French state |

| Known for | Sentencing the victims of police brutality during the Clichy affair to harsh prison terms |

Edmond Benoît or Édouard Benoît, born on 20 April 1843 in La Baule-Escoublac and dead on 27 June 1909 in the 11th arrondissement of Paris, was a magistrate, judge, and president of the Court of Appeal of Paris.

He is primarily known for his handling of the Clichy affair, where he didn't prosecute police officers responsible for violence and instead sentenced the anarchist victims to harsh penalties. This treatment sparked the beginning of a period the public dubbed the Ère des attentats (1892-1894), when, in an act of vengeance, anarchist militants Ravachol, Soubère, Jas-Béala, and Simon united to target his home in the Saint-Germain bombing.

He died in Paris in 1909.

Biography

Édouard 'Edmond' Marie Joseph Benoît was born in La Baule-Escoublac on 20 April 1843.[1] He was the son of Céline Boulanger and Édouard Benoît.[1]

Benoît pursued a career in the judiciary, becoming a deputy public prosecutor in 1869.[2] In 1870, he was appointed public prosecutor at the First instance court in Châteaubriant. He then became deputy prosecutor general in Angers, followed by deputy prosecutor at the First instance court in Vannes.[2] In 1876, he was promoted to public prosecutor at the First instance court in Quimperlé.[2] Two years later, in 1878, he resumed this role in Vannes. In 1880, he was named public prosecutor at the First instance court in Troyes.[2]

In 1882, Benoît was appointed investigating judge at the First instance court. In 1887, he became a counselor at the Court of Appeal of Paris.[2]

Clichy affair

On 1 May 1891, a group of anarchists gathered in Levallois-Perret for a peaceful demonstration and headed towards Clichy.[3] The police commissaire of Levallois-Perret attempted to intercept them with his officers, while the Clichy commissaire refused to intervene, not considering them an undue disturbance.[3] The anarchists stopped the demonstration and retreated to a wine merchant's premises.[3] The Levallois-Perret police commissaire then entered his neighbor's jurisdiction and tried to seize the red flag the group had brought to the merchant's.[3] A fight broke out and shots were exchanged before the police fired on the fleeing demonstrators, seizing three of them: Henri Decamps, Charles Dardare, and Louis Léveillé. They were taken to the police station and then beaten by the police – one of them nearly killed by an officer's saber.[3]

Benoît was in charge of the trial, which took place in August of the same year. The prosecutor, Léon Bulot, demanded the death penalty for the three victims and he paid little attention to their defense.[3] Benoît sentenced them to heavy penalties relative to the accusations against them, with Decamps and Dardare receiving three and five years in prison respectively.[3][4]

Saint-Germain bombing

.png)

The Clichy affair sparked outrage among a segment of French society, but it particularly impacted anarchists.[3][4] The events—the police forcibly seizing a flag from a peaceful demonstration, the arrested individuals being beaten, and the harsh judicial handling of the case—sent a shockwave through the anarchist movement in France.[3][4]

During this period, anarchists were engaging in propaganda of the deed—a strategy aimed at conveying ideas through action rather than discourse.[6] This manifested, among other ways, in acts of a terrorist nature, particularly the assassinations of political figures or bomb attacks targeting symbols.[6] The Clichy affair ultimately convinced a number of anarchists that vengeance against those responsible for their repression would be legitimate.[3][4]

Consequently, Ravachol, an anarchist from Saint-Étienne who was in Paris while on the run, met Henri Decamps' wife there.[4] This encounter persuaded him to target the magistrates responsible for the trial. On 11 March 1892, Ravachol and other accomplices, including Rosalie Soubère, Joseph Jas-Béala, and Charles Simon, carried out the Saint-Germain bombing.[4] This was one of the first attacks of what the public called the Ère des attentats (1892-1894), a two-year period during which numerous anarchist attacks occurred in France.[4][7]

The bombing resulted in no fatalities, did not affect judge Benoît, who resided on the fifth floor, and injured one person.[7] The judge spoke out in the Bonapartist newspaper L'Autorité a few days later, stating, among other things, that the most harshly condemned person would have received a two-year sentence, according to what he claimed to the newspaper:[8]

It is absolutely false that I have ever, at any time, received threatening letters. Of course, in my capacity as investigating judge, which I held until 1887, I often dealt with anarchists; but I never noticed any of them showing me any particular animosity. Since then, in my new capacity as counselor at the Court of Appeal, I have had to preside over the proceedings of several anarchist trials, and in particular, last year, those of the Saint-Denis anarchists [i.e., from the Clichy affair]. But, if you recall that the jury treated them very leniently and that the most severely condemned defendant only received two years in prison, you will doubtless not find that the anarchists have grounds to retaliate against me.

Later years and death

In 1904, he was appointed president of the Court of Appeal of Paris.[2] He died on 27 June 1909 in the 11th arrondissement of Paris.[1]

References

- ^ a b c French authorities (27 June 1909). "Death certificate of Édouard Marie Joseph BENOIT". Archives de Paris. p. 9.

- ^ a b c d e f "Édouard Marie Joseph Benoît". Annuaire rétrospectif de la magistrature XIXe-XXe siècles (in French). 2010-06-12. Archived from the original on 2023-10-27. Retrieved 2025-07-25.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Bouhey 2008, p. 240-245.

- ^ a b c d e f g Merriman 2016, p. 71-74.

- ^ "L'Illustration : Journal universel". 1892.

- ^ a b Eisenzweig 2001, p. 72-75.

- ^ a b Merriman 2016, p. 70-90.

- ^ Benoît, Edmond (13 March 1892). "Déclaration de M. Benoît" [Declaration of Mr. Benoît]. L'Autorité: 2.

Bibliography

- Bouhey, Vivien (2008), Les Anarchistes contre la République [The Anarchists against the Republic] (in French), Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes (PUR)

- Eisenzweig, Uri (2001). Fictions de l'anarchisme [Fictions of anarchism] (in French). France: C. Bourgois. ISBN 2-267-01570-6.

- Merriman, John M. (2016). The dynamite club: how a bombing in fin-de-siècle Paris ignited the age of modern terror. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-21792-6.