Dyskinetic cerebral palsy

| Dyskinetic cerebral palsy | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Athetoid cerebral palsy |

| |

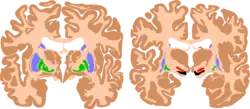

| The basal ganglia plays essential roles in voluntary motor function. Various forms of damage to the basal ganglia can cause a range of movement disorders. | |

| Symptoms | Dystonia, choreoathetosis |

| Usual onset | Birth |

| Duration | Lifelong |

| Causes | Perinatal asphyxia, neonatal shock, hyperbilirubinaemia |

| Treatment | Supportive |

Dyskinetic cerebral palsy (DCP), also known as athetoid cerebral palsy or ADCP, is a subtype of cerebral palsy that is characterized by dystonia, choreoathetosis, and impaired control of voluntary movement.[1][2] Unlike spastic or ataxic cerebral palsies, dyskinetic cerebral palsy is characterized by both hypertonia and hypotonia, due to the affected individual's inability to control muscle tone.[3][4] Clinical diagnosis of ADCP typically occurs within 18 months of birth and is primarily based upon motor function and neuroimaging techniques.[5][6] While there are no cures for ADCP, some drug therapies as well as speech therapy, occupational therapy, and physical therapy have shown capacity for treating the symptoms.

Like other forms of CP, it is primarily associated with damage to the basal ganglia in the form of lesions that occur during brain development due to bilirubin encephalopathy and hypoxic–ischemic brain injury.[7]

Classification of cerebral palsy can be based on severity, topographic distribution, or motor function. Severity is typically assessed via the Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) or the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (described further below).[4] Classification based on motor characteristics classifies CP as occurring from damage to either the corticospinal pathway or extrapyramidal regions.[3] Athetoid dyskinetic cerebral palsy is a non-spastic, extrapyramidal form of cerebral palsy (spastic cerebral palsy, in contrast, results from damage to the brain's corticospinal pathways).[3]

Presentation

In dyskinetic cerebral palsy (DCP), both motor and non-motor impairments are present. Impaired regulation of muscle tone, lack of muscle control, and bone deformations are often more severe compared to the other subtypes of cerebral palsy (CP).[8] Severity of non-motor impairments is generally correlated with motor symptom severity.

The primary motor signs of DCP are dystonia and choreoathetosis. Dystonia is defined by twisting and repetitive movements, abnormal postures due to sustained muscle contractions, and hypertonia. Dystonia is aggravated by voluntary movements and postures, or with stress, emotion or pain.[9][10] Choreoathetosis is characterized by hyperkinesia (chorea i.e. rapid involuntary, jerky, often fragmented movements) and hypokinesia (athetosis i.e. slower, constantly changing, writhing or contorting movements).[11][12] Dystonia and choreoathetosis often occur concurrently in DCP.[12] Both increase with activity and are generalized over all body regions with a higher severity in the upper limbs than in the lower limbs. Dystonia has a significantly higher level of severity in the distal parts of the extremities, whereas choreoathetosis is more equally distributed.[2] Severity of dystonia but not choreoathetosis is correlated with higher levels of functional disability on the Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS).[13][2]

Approximately half of the individuals with DCP have severe learning disabilities. Epilepsy, visual impairments, and hearing impairments are reported in 51%, 45%, and 11% of individuals with DCP, respectively. Dysarthria or anarthria are also common.[8][14]

Involuntary movements often increase during periods of emotional stress or excitement and disappear when the patient is sleeping or distracted.[7] Patients experience difficulty in maintaining posture and balance when sitting, standing, and walking due to these involuntary movements and fluctuations in muscle tone.[5] Coordinated activities such as reaching and grasping may also be challenging.[5] Muscles of the face and tongue can be affected, causing involuntary facial grimaces, expressions, and drooling.[5] Speech and language disorders, known as dysarthria, are common in athetoid CP patients.[3] In addition, ADCP patients may have trouble eating.[5] Hearing loss is a common co-occurring condition,[4] and visual disabilities can be associated with Athetoid Cerebral Palsy. Squinting and uncontrollable eye movements may be initial signs and symptoms. Children with these disabilities rely heavily on visual stimulation, especially those who are also affected by sensory deafness.[15]

Causes

Dyskinetic cerebral palsy could have multiple causes. The majority of the children are born at term and experience perinatal adverse events which can be supported by neuroimaging. Possible causes are perinatal hypoxic-ischaemia and neonatal shock in children born at term or near term. Hyperbilirubinaemia used to be a common contributing factor,[16] but is now rare in high-income countries due to preventive actions. Other aetiological factors are growth retardation,[17] brain maldevelopment, intracranial haemorrhage, stroke or cerebral infections.[8]

CP in general is a non-progressive, neurological condition that results from brain injury and malformation occurring before cerebral development is complete.[3] ADCP is associated with injury and malformations to the extrapyramidal tracts in the basal ganglia or the cerebellum.[7] Lesions to this region principally arise via hypoxic ischemic brain injury or bilirubin encephalopathy.[7]

Hypoxic-ischemic brain injury

Hypoxic-ischemic brain injury is a form of cerebral hypoxia in which oxygen cannot perfuse to cells in the brain. Lesions in the putamen and thalamus caused by this type of brain injury are primary causes of ADCP and can occur during the prenatal period and shortly after.[7] Lesions that arise after this period typically occur as a result of injury or infections of the brain.[18]

Bilirubin encephalopathy

Bilirubin encephalopathy, also known as kernicterus, is the accumulation of bilirubin in the grey matter of the central nervous system. The main accumulation targets of hyperbilirubinemia are the basal ganglia, ocular movement nucleus, and acoustic nucleus of the brainstem.[7] Pathogenesis of bilirubin encephalopathy involves several factors, including the transport of bilirubin across the blood–brain barrier and into neurons.[7] Mild disruption results in left cognition impairment, while severe disruption results in ADCP.[7] Lesions caused by accumulation of bilirubin occur mainly in the global pallidus and hypothalamus.[7] Disruption of the blood–brain barrier by disease or a hypoxic ischemic injury can also contribute to an accumulation of bilirubin in the brain.[7] Bilirubin encephalopathy leading to cerebral palsy has been greatly reduced by effective monitoring and treatment for hyperbilirubinemia in preterm infants.[7] As kernicterus has decreased due to improvements in care, over the last 50 years the proportion of children developing athetoid CP has decreased.[19] In most cases, will have normal intelligence.

Diagnosis

Cerebral palsies have historically been diagnosed based on parental reporting of developmental motor delays such as failure to sit upright, reach for objects, crawl, stand, or walk at the appropriate age.[5] Diagnosis of ADCP is also based on clinical assessment used in conjunction with milestone reporting.[4] The majority of ADCP assessments now use the Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) or the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (formerly the International Classification of Impairments Disease, and Handicaps), measures of motor impairment that are effective in assessing severe CP.[7][4] The Barry-Albright Dystonia Rating Scale (BADS), the Burke-Fahn-Marsden Dystonia Rating Scale (BFMS) and the Dyskinesia Impairment Scale (DIS) are also commonly used to categorize clinical qualitative assessments of dyskinesia in DCP.[20][21][22]

Neuroimaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is used to detect morphological brain abnormalities associated with ADCP in patients that are either at risk for ADCP or have shown symptoms thereof.[6] The abnormalities chiefly associated with ADCP are lesions that appear in the basal ganglia.[6] The severity of the disease is proportional to the severity and extent of these abnormalities, and is typically greater when additional lesions appear elsewhere in the deep grey matter or white matter.[6] MRI also has the ability to detect brain malformation, periventricular leukomalacia (PVL), and areas affected by hypoxia-ischemia, all of which may play a role in the development of ADCP.[4] The MRI detection rate for ADCP is approximately 54.5%, however this statistic varies depending on the patient's age and the cause of the disease and has been reported to be significantly higher.[7]

Multiple classification systems using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have been developed, linking brain lesions to time of birth, cerebral palsy subtype and functional ability.[23][24][25][26] Around 70% of patients with DCP show lesions in the cortical and deep grey matter of the brain, more specifically in the basal ganglia and thalamus. However, other brain lesions and even normal-appearing MRI findings can occur, for example white matter lesions and brain maldevelopments.[2][25][27][28] Patients with pure basal ganglia and thalamus lesions are more likely to show more severe choreoathetosis whereas dystonia may be associated with other brain lesions, such as the cerebellum.[2] These lesions occur mostly during the peri- and postnatal period since these regions have a high vulnerability during the late third trimester of the pregnancy.[29] Unfortunately, contemporary imaging is not sophisticated enough to detect all subtle brain deformities and network disorders in dystonia. Research with more refined imaging techniques including diffusion tensor imaging and functional MRI is required.[10][30]

Motor function

Movement and posture limitations are aspects of all CP types and as a result, CP has historically been diagnosed based on parental reporting of developmental motor delays such as failure to sit upright, reach for objects, crawl, stand, or walk at the appropriate age.[5] Diagnosis of ADCP is also based on clinical assessment used in conjunction with milestone reporting.[4] The majority of ADCP assessments now use the Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) or the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (formerly the International Classification of Impairments Disease, and Handicaps), measures of motor impairment that are effective in assessing severe CP.[7][4] ADCP is typically characterized by an individual's inability to control their muscle tone, which is readily assessed via these classification systems.[7][4]

Prevention

Prevention strategies have been developed for the different risk factors of the specific cerebral palsy subtypes. Primary prevention consists of reducing the possible risk factors. However, when multiple risk factors cluster together, prevention is much more difficult. Secondary preventions may be more appropriate at that time, e.g. prevention of prematurity. Studies showed a reduced risk of cerebral palsy when administering magnesium sulfate to women at risk of preterm delivery.[31][32] Cooling or therapeutic hypothermia for 72 hours immediately after birth has a significant clinical effect on reducing mortality and severity of neurodevelopmental disabilities in neonates with perinatal asphyxia. This has been documented for newborns with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy.[33][34]

Management

Dyskinetic cerebral palsy is a non-progressive, irreversible disease. The current management is symptomatic, since there is no cure. The main goal is to improve daily activity, quality of life and autonomy of the children by creating a timed and targeted management. The many management options for patients with DCP are not appropriate as standalone treatment but must be seen within an individualized multidisciplinary rehabilitation program. Medical treatment consists of oral medication and surgery. Before using oral drugs, it is important to differentiate between spasticity, dystonia, and choreoathetosis since each motor disorder has a specific approach. In general, many oral drugs have low efficacy, unwanted side-effects and variable effects.[35]

Orthopedic surgery is performed to correct musculoskeletal deformities, but it is recommended that all other alternatives are considered first.[10]

The previous management options need to be combined with rehabilitation programs, adapted to the specific needs of each individual. Typically, the team of caregivers can consist of physiotherapists, occupational therapists and speech/communication therapists. The therapy mainly focusses on the motor problems by using principles of neuroplasticity, patterning, postural balance, muscle strengthening and stretching.[36] Non-motor impairments such as epilepsy require specific treatment.

Physical and occupational therapy

Physical therapy and Occupational Therapy are staple treatments of ADCP. Physical therapy is initiated soon after diagnosis and typically focuses on trunk strength and maintaining posture.[7] Physical therapy helps to improve mobility, range of motion, functional ability, and quality of life. Specific exercises and activities prescribed by a therapist help to prevent muscles from deteriorating or becoming locked in position and help to improve coordination.[37]

Speech therapy

Speech impairment is common in ADCP patients.[4][3] Speech therapy is the treatment of communication diseases, including disorders in speech production, pitch, intonation, respiration and respiratory disorders. Exercises advised by a speech therapist or speech-language pathologist help patients to improve oral motor skills, restore speech, improve listening skills, and use communication aids or sign language if necessary.[37]

Drug therapy

Oral baclofen and trihexyphenidyl are commonly used to decrease dystonia, although its efficacy is relatively low in most patients. Adverse effects of the latter can include worsening of choreoathetosis.[10] Since dystonia predominates over choreoathetosis in most patients, reducing dystonia allows the possibility of a full expression of choreoathetosis. This suggests that the discrimination of dystonia and choreoathetosis is crucial, since misinterpretations in diagnosing can contribute to the administration of inappropriate medication, causing unwanted effects.[10][38] Intrathecal baclofen pumps (ITB) are often used as an alternative to reduce side-effects of the oral dystonic medication over the whole body.[39] Botulinum toxin injections may be applied to decrease dystonia in specific muscles or muscle groups.[10][36][40]

Medications that impede the release of excitatory neurotransmitters have been used to control or prevent spasms.[41] Treatment with intrathecal baclofen, a gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) agonist, decreases muscle tone and has been shown to decrease the frequency of muscle spasms in ADCP patients.[41] Tetrabenazine, a drug commonly used in the treatment of Huntington's disease, has been shown to be effective treating chorea.[41]

Deep brain stimulation

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is a technique that uses electrodes placed in the brain to modify brain activity by sending a constant electrical signal to the nearby nuclei.[41] Treatment of muscle tone issues via deep brain stimulation typically targets the global pallidus and has shown to significantly improve symptoms associated with ADCP.[41] The specific mechanism by which DBS affects ADCP is unclear.[41] DBS of the globus pallidus interna improves dystonia in people with dyskinetic CP in 40% of cases, perhaps due to variation in basal ganglia injuries.[42]

DBS in patients with DCP has shown to decrease dystonia.[43][44] However, the responsiveness is less beneficial and the effects are more variable than in patients with inherited or primary dystonia.[45] The effects on choreoathetosis have not been investigated.

Prognosis

The severity of impairment and related prognosis is dependent on the location and severity of brain lesions.[7] Up to 75% of patients will achieve some degree of ambulation.[3] Speech problems, such as dysarthria, are common to these patients.[3]

Prevalence

Dyskinetic cerebral palsy is the second most common subtype of cerebral palsy after spastic CP. A European Cerebral Palsy study reported a rate of 14.4% of patients with DCP[46] which is similar to the rate of 15% reported in Sweden.[47] The rate appeared lower in Australia, where data from states with full population-based ascertainment listed DCP as the predominant motor type in only 7% of the cases.[48] The differences reported from various registers and countries may relate to under-identification of dyskinetic CP due to a lack of standardization in definition and classification based on predominant type.[49][11]

References

- ^ Rosenbaum P, Paneth N, Leviton A, Goldstein M, Bax M, Damiano D, et al. (February 2007). "A report: the definition and classification of cerebral palsy April 2006". Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 49 (6): 8–14. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.tb12610.x.

- ^ a b c d e Monbaliu E, de Cock P, Ortibus E, Heyrman L, Klingels K, Feys H (February 2016). "Clinical patterns of dystonia and choreoathetosis in participants with dyskinetic cerebral palsy". Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 58 (2): 138–144. doi:10.1111/dmcn.12846. PMID 26173923.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Jones MW, Morgan E, Shelton JE (2007). "Cerebral palsy: introduction and diagnosis (part I)". Journal of Pediatric Health Care. 21 (3): 146–152. doi:10.1016/j.pedhc.2006.06.007. PMID 17478303.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j O'Shea MT (2008). "Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of cerebral palsy in near-term/ term infants". Clin Obstet Gynecol. 51 (4): 816–828. doi:10.1097/GRF.0b013e3181870ba7. PMC 3051278. PMID 18981805.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Athetoid Dyskinetic". Swope, Rodante P.A. Retrieved 31 October 2012.

- ^ a b c d Krägeloh-Mann I, Horber V (2007). "The role of magnetic resonance imaging in elucidating the pathogenesis of cerebral palsy: a systematic review". Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 49 (2): 144–151. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.00144.x. ISSN 0012-1622. PMID 17254004. S2CID 6967370.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Hou M, Zhao J, Yu R (2006). "Recent advances in dyskinetic cerebral palsy" (PDF). World J Pediatr. 2 (1): 23–28.

- ^ a b c Himmelmann K, Hagberg G, Wiklund LM, Eek MN, Uvebrant P (April 2007). "Dyskinetic cerebral palsy: a population-based study of children born between 1991 and 1998". Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 49 (4): 246–251. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.00246.x. PMID 17376133.

- ^ Sanger TD, Chen D, Fehlings DL, Hallett M, Lang AE, Mink JW, et al. (August 2010). "Definition and classification of hyperkinetic movements in childhood". Movement Disorders. 25 (11): 1538–1549. doi:10.1002/mds.23088. PMC 2929378. PMID 20589866.

- ^ a b c d e f Monbaliu E, Himmelmann K, Lin JP, Ortibus E, Bonouvrié L, Feys H, et al. (September 2017). "Clinical presentation and management of dyskinetic cerebral palsy". Lancet Neurology. 16 (9): 741–749. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30252-1. PMID 28816119. S2CID 22841349.

- ^ a b Cans C, Dolk H, Platt M, Colver A, Prasauskiene A, Krägeloh-Mann I (February 2007). "Recommendations from the SCPE collaborative group for defining and classifying cerebral palsy". Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 49 (s109): 35–38. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.tb12626.x. PMID 17370480.

- ^ a b Sanger TD, Delgado MR, Gaebler-Spira D, Hallett M, Mink JW (January 2003). "Classification and Definition of Disorders Causing Hypertonia in Childhood". Pediatrics. 111 (1): e89 – e97. doi:10.1542/peds.111.1.e89. PMID 12509602.

- ^ Monbaliu E, De Cock P, Mailleux L, Dan B, Feys H (March 2017). "The relationship of dystonia and choreoathetosis with activity, participation and quality of life in children and youth with dyskinetic cerebral palsy". European Journal of Paediatric Neurology. 21 (2): 327–335. doi:10.1016/j.ejpn.2016.09.003. PMID 27707657.

- ^ Himmelmann K, McManus V, Hagberg G, Uvebrant P, Krägeloh-Mann I, Cans C (May 2009). "Dyskinetic cerebral palsy in Europe: trends in prevalence and severity". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 94 (12): 921–926. doi:10.1136/adc.2008.144014. PMID 19465585. S2CID 25093584.

- ^ Black P (1982). "Visual Disorders Associated with Cerebral Palsy". British Journal of Ophthalmology. 66 (1): 46–52. doi:10.1136/bjo.66.1.46. PMC 1039711. PMID 7055543.

- ^ Kyllerman M, Bager B, Bensch J, Bille B, Olow I, Voss H (July 1982). "Dyskinetic cerebral palsy. I. Clinical categories, associated neurological abnormalities and incidences". Acta Paediatrica. 71 (4): 543–550. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.1982.tb09472.x. PMID 7136669. S2CID 40382546.

- ^ Jarvis S, Glinianaia S, Torrioli MG, Platt MJ, Miceli M, Jouk PS, et al. (October 2003). "Cerebral palsy and intrauterine growth in single births: European collaborative study". Lancet. 362 (9390): 1106–1111. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14466-2. PMID 14550698. S2CID 21236988.

- ^ Facts about cerebral palsy. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012).

- ^ Robin C. Meyers, Steven J. Bachrach, Virginia A. Stallings (2017). "Cerebral Palsy". In Shirley W. Ekvall, Valli K. Ekvall (eds.). Pediatric and Adult Nutrition in Chronic Diseases, Developmental Disabilities, and Hereditary Metabolic Disorders: Prevention, Assessment, and Treatment. Oxford Scholarship Online. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199398911.003.0009. ISBN 9780199398911. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ^ Barry MJ, VanSwearingen JM, Albright AL (June 1999). "Reliability and responsiveness of the Barry–Albright Dystonia Scale". Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 41 (6): 404–411. doi:10.1017/s0012162299000870. PMID 10400175.

- ^ Burke RE, Fahn S, Marsden CD, Bressman SB, Moskowitz C, Friedman J (January 1985). "Validity and reliability of a rating scale for the primary torsion dystonias". Neurology. 35 (1): 73–77. doi:10.1212/wnl.35.1.73. PMID 3966004. S2CID 40488467.

- ^ Monbaliu E, Ortibus E, De Cat J, Dan B, Heyrman L, Prinzie P, et al. (March 2012). "The Dyskinesia Impairment Scale: a new instrument to measure dystonia and choreoathetosis in dyskinetic cerebral palsy". Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 54 (3): 278–283. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2011.04209.x. PMID 22428172.

- ^ Krägeloh-Mann I, Horber V (February 2007). "The role of magnetic resonance imaging in elucidating the pathogenesis of cerebral palsy: a systematic review". Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 49 (2): 144–151. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.00144.x. PMID 17254004.

- ^ Himmelmann K, Horber V, De La Cruz J, Horridge K, Mejaski-Bosnjak V, Hollody K, et al. (January 2017). "MRI classification system (MRICS) for children with cerebral palsy: development, reliability, and recommendations". Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 59 (1): 57–64. doi:10.1111/dmcn.13166. PMID 27325153.

- ^ a b Benini R, Dagenais L, Shevell MI (February 2013). "Normal Imaging in Patients with Cerebral Palsy: What Does It Tell Us?". The Journal of Pediatrics. 162 (2): 369–374.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.07.044. PMID 22944004.

- ^ Reid SM, Dagia CD, Ditchfield MR, Carlin JB, Reddihough DS (March 2014). "Population-based studies of brain imaging patterns in cerebral palsy". Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 56 (3): 222–232. doi:10.1111/dmcn.12228. PMID 23937113.

- ^ Horber V, Sellier E, Horridge K, Rackauskaite G, Andersen GL, Virella D, et al. (March 2020). "The Origin of the Cerebral Palsies: Contribution of Population-Based Neuroimaging Data". Neuropediatrics. 51 (2): 113–119. doi:10.1055/s-0039-3402007. PMID 32120429. S2CID 211835380.

- ^ Krägeloh-Mann I, Cans C (August 2009). "Cerebral palsy update". Brain and Development. 31 (7): 537–544. doi:10.1016/j.braindev.2009.03.009. PMID 19386453. S2CID 8374616.

- ^ Krägeloh-Mann I (November 2004). "Imaging of early brain injury and cortical plasticity". Experimental Neurology. 190 (Suppl 1): 84–90. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.05.037. PMID 15498546. S2CID 9500238.

- ^ Korzeniewski SJ, Birbeck G, DeLano MC, Potchen MJ, Paneth N (February 2008). "A Systematic Review of Neuroimaging for Cerebral Palsy". Journal of Child Neurology. 23 (2): 216–227. doi:10.1177/0883073807307983. PMID 18263759. S2CID 11724552.

- ^ Conde-Agudelo A, Romero R (June 2009). "Antenatal magnesium sulfate for the prevention of cerebral palsy in preterm infants less than 34 weeks' gestation: a systematic review and metaanalysis". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 200 (6): 595–609. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2009.04.005. PMC 3459676. PMID 19482113.

- ^ Graham HK, Rosenbaum P, Paneth N, Dan B, Lin JP, Damiano DL, et al. (January 2016). "Cerebral palsy". Nature Reviews Disease Primers. 2 15082. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2015.82. PMC 9619297. PMID 27188686. S2CID 4037636.

- ^ Jacobs SE, Hunt R, Tarnow-Mordi WO, Inder TE, Davis PG (December 2008). "Cochrane Review: Cooling for newborns with hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy". Evidence-Based Child Health. 3 (4): 1049–1115. doi:10.1002/ebch.293.

- ^ Azzopardi DV, Strohm B, Edwards AD, Dyet L, Halliday HL, Juszczak E, et al. (October 2009). "Moderate Hypothermia to Treat Perinatal Asphyxial Encephalopathy". New England Journal of Medicine. 361 (14): 1349–1358. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0900854. PMID 19797281. S2CID 27308372.

- ^ Lumsden DE, Kaminska M, Tomlin S, Lin JP (July 2016). "Medication use in childhood dystonia". European Journal of Paediatric Neurology. 20 (4): 625–629. doi:10.1016/j.ejpn.2016.02.003. PMID 26924167.

- ^ a b Colver A, Fairhurst C, Pharoah PO (April 2014). "Cerebral palsy". Lancet. 383 (9924): 1240–1249. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61835-8. PMID 24268104. S2CID 24655659.

- ^ a b "Cerebral Palsy Treatments". Education That Works. Archived from the original on 22 January 2013. Retrieved 31 October 2012.

- ^ Termsarasab P (December 2017). "Medical treatment of dyskinetic cerebral palsy: translation into practice". Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 59 (12): 1210. doi:10.1111/dmcn.13549. PMID 28892137.

- ^ Bonouvrié LA, Becher JG, Vles JS, Boeschoten K, Soudant D, de Groot V, et al. (October 2013). "Intrathecal baclofen treatment in dystonic cerebral palsy: a randomized clinical trial: the IDYS trial". BMC Pediatrics. 13 175. doi:10.1186/1471-2431-13-175. PMC 3840690. PMID 24165282.

- ^ Elkamil AI, Andersen GL, Skranes J, Lamvik T, Vik T (September 2012). "Botulinum neurotoxin treatment in children with cerebral palsy: A population-based study in Norway". European Journal of Paediatric Neurology. 16 (5): 522–527. doi:10.1016/j.ejpn.2012.01.008. PMID 22325829.

- ^ a b c d e f Lundy C, Lumsden D, Fairhurst C (2009). "Treating complex movement disorders in children with cerebral palsy". The Ulster Medical Journal. 78 (3): 157–163. PMC 2773587. PMID 19907680.

- ^ Aravamuthan BR, Waugh JL (January 2016). "Localization of Basal Ganglia and Thalamic Damage in Dyskinetic Cerebral Palsy". Pediatric Neurology. 54: 11–21. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2015.10.005. PMID 26706479.

- ^ Coubes P, Roubertie A, Vayssiere N, Hemm S, Echenne B (June 2000). "Treatment of DYT1-generalised dystonia by stimulation of the internal globus pallidus". Lancet. 355 (9222): 2220–2221. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02410-7. PMID 10881900. S2CID 12077880.

- ^ Koy A, Timmermann L (January 2017). "Deep brain stimulation in cerebral palsy: Challenges and opportunities". European Journal of Paediatric Neurology. 21 (1): 118–121. doi:10.1016/j.ejpn.2016.05.015. PMID 27289260.

- ^ Vidailhet M, Yelnik J, Lagrange C, Fraix V, Grabli D, Thobois S, et al. (August 2009). "Bilateral pallidal deep brain stimulation for the treatment of patients with dystonia-choreoathetosis cerebral palsy: a prospective pilot study". Lancet Neurology. 8 (8): 709–717. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70151-6. PMID 19576854. S2CID 24345609.

- ^ Bax M, Tydeman C, Flodmark O (October 2006). "Clinical and MRI Correlates of Cerebral Palsy". JAMA. 296 (13): 1602–1608. doi:10.1001/jama.296.13.1602. PMID 17018805.

- ^ Himmelmann K, Hagberg G, Beckung E, Hageberg B, Uvebrant P (March 2005). "The changing panorama of cerebral palsy in Sweden. IX. Prevalence and origin in the birth-year period 1995-1998". Acta Paediatrica. 94 (3): 287–294. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.2005.tb03071.x. PMID 16028646. S2CID 8322621.

- ^ Report of the Australian Cerebral Palsy Register Birth years 1995-2012 (Report). The Australian Cerebral Palsy Register Group. November 2018.

- ^ Cans C (February 2007). "Surveillance of cerebral palsy in Europe: a collaboration of cerebral palsy surveys and registers". Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 42 (12): 816–824. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2000.tb00695.x.