Dictionary of the Khazars

| |

| Author | Milorad Pavić |

|---|---|

| Original title | Хазарски речник; Hazarski rečnik |

| Translator | Christina Pribicevic-Zoric |

| Language | Serbian |

| Genre | Postmodern literature |

| Publisher | Prosveta |

Publication date | 1984 |

| Publication place | Yugoslavia |

Published in English | 1988 |

| Media type | Print (hardback and paperback) |

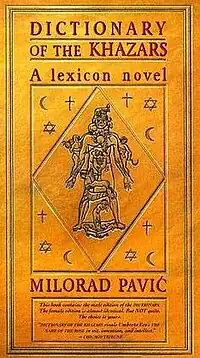

Dictionary of the Khazars: A Lexicon Novel (Serbian Cyrillic: Хазарски речник, Hazarski rečnik) is the first novel by Serbian writer Milorad Pavić, published in 1984. Originally written in Serbian, the novel has been translated into many languages. It was first published in English by Knopf, New York City, in 1988.[1]

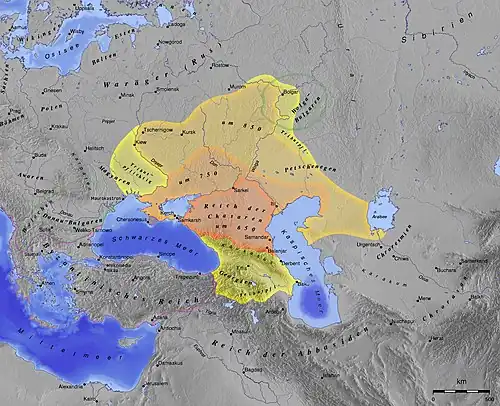

There is no easily discerned plot in the conventional sense, but the central question of the book (the mass religious conversion of the Khazar people) is based on a historical event generally dated to approximately "740 AD" and the last decades of the 8th century when the Khazar royalty and nobility converted to Judaism, and part of the general population followed.[2] There are more or less three different significant time periods depicted in the novel. The first period takes place between the 7th and 11th centuries and is mainly composed of stories loosely linked to the Khazar conversion to monotheistic religion. The second period takes place during the 17th century, and includes stories about the lives of the compilers of the in-universe Khazar Dictionary and their contemporaries. The third briefly takes place in the 1960s and 70s, but mostly in the 1980s, and includes stories of academics in areas that in some way have to do with the Khazars. There are also references to things that happened outside of these periods, such as the talk of primordial beings like Adam Ruhani and Adam Cadmon.

Most of the characters and events described in the novel are entirely fictional, as is the culture ascribed to the Khazars in the book, which bears little resemblance to any literary or archeological evidence.

The novel takes the form of three cross-referenced mini-encyclopedias, sometimes contradicting each other, each compiled from the sources of one of the major Abrahamic religions (Christianity, Islam, and Judaism). In his introduction to the work, Pavić wrote:

No chronology will be observed here, nor is one necessary. Hence each reader will put together the book for himself, as in a game of dominoes or cards, and, as with a mirror, he will get out of this dictionary as much as he puts into it, for you [...] cannot get more out of the truth than what you put into it.[3]

The book comes in two different editions, one "male" and one "female", which differ in only a critical passage in a single paragraph.[4]

In 1984, Pavić stated that the Khazars were a metaphor for a small people surviving in between great powers and great religions. In Yugoslavia, Pavić stated five years later, Serbs recognized their own fate; it was the same in Slovenia and elsewhere, a schoolbook on survival. The same in Hungary and Czechoslovakia, and on and on. A French critic said, 'We are all Khazars in the age of nuclear threat and poisoned environment.'[5]

A ballet adaption of the Dictionary of the Khazars was staged at Madlenianum Opera and Theatre.[6] A play based on the novel has also been staged in the New Riga Theatre.

How to Use the Dictionary

In the introductory "How to Use the Dictionary", the author notes that the dictionary "has a register, concordances, and entries, like a holy book or a crossword puzzle, and all the names or subjects marked with the small sign of the cross, the crescent, the Star of David, or some other symbol can be looked up in the corresponding book of this dictionary for more explanation."[7]

These symbols appear on the cover of the book. The reference to the "other symbol" can encompass a rhombus, dual triangles sharing a common base instead of the dyad that is distinctly Hebrew. Across a variety of cultures, the rhombus represents a gateway into the total unity of masculine and feminine binaries, as well as the heavens and earth joined in a fertile cycle of death and rebirth.[8]

Preserved Fragments from the Introduction to the Destroyed 1691 Edition of the Dictionary

The second of four fragments preserved from the 1691 Hebrew lexicon became known as the "triangle" parable by critics (below). The Hebrew fragment, translated from Latin, prompts readers to "imagine two men holding a captured puma on a rope. If they want to approach each other, the puma will attack, because the rope will slacken; only if they both pull simultaneously on the rope is the puma equidistant from the two of them. That is why it is so for him [male edition] who reads and him who writes to reach each other: between them lies a mutual thought captured on ropes that they pull in opposite directions."[9]

Compositional model

The Khazar dictionary is a novel in the form of a dictionary: it is divided into sections (lexicon/encyclopedia articles), which are interconnected according to the hypertext model - they contain signs that refer the reader to other sections, so that he can, like using hypertext on the Internet, choose his reading path by following 'links'. This achieves non-linearity in reading, which is one of the most famous features of postmodern literature.

Apart from being organized into a network through hypertext, Pavić's novel aspires to other spatial transformations, since it has an almost geometric structure: it consists of three books - Red, Green and Yellow (the colors metonymically denote Christianity, Islam and Judaism), and three time layers - medieval, seventeenth century and twentieth century, which is why the interpretive model of this novel is called the Khazar prism in the literature. Different books and layers are connected by dynamic links, both explicit (hypertextual) and implicit (through motifs, themes, characters).

The three-layered story

This is a story about the rise and fall of a people and civilization.

- Three books: The Red Book provides Christian sources on the Khazar issue, the Green Book provides Islamic sources, and the Yellow Book provides Jewish sources.

- Three time layers:

I - The Middle Ages, the time of the Khazar polemic

II - The 17th century (the time of the first edition of the dictionary, and the main actors of the story are Avram Brankovich, Yusuf Masudi, and Samuel Cohen, who are listed as one of the writers of this book)

III - events from the 20th century follow university professors (Dr. Abu Kabir Muawia, Dr. Isailo Suk and Dr. Dorothea Schultz), who are researching Khazar history.

The Khazar polemic is a central event in the Khazar Dictionary. According to ancient chronicles, the Khazar ruler, the kaghan, had a dream and sought three philosophers to interpret it for him. This was a matter of importance to the Khazar state, because the kaghan had decided to convert, together with his people, to the faith of the sage who would give the most satisfactory dream interpretation.

The first interpreter (participant in this polemic) was Constantine of Thessaloniki - Cyril, and he expounded the foundations of Christianity. The Islamic representative was al-Farabi and the Jewish Yitzhak ha-Sangari.

In accordance with the number three, the novel also features characters from three hells: Sevast (Satan), Akshani (Shaitan), and Ephorsinia (a demon from the Hebrew hell).

A textual primary source base for the lexical entries is almost completely absent or consists of fragments. Hypertext anchors and target entries mutually rest on, and severally support, the narrated presence of traditions, myths, and ethnonyms. That is, hypertextual content, both mutually exclusive and mutually inclusive, substantiates itself. The Red Book claims that they converted to Christianity. The Green Book to Islam and the Yellow Book to Judaism. Dual editions of the tri-layered lexicon, male and female, externally maintain and internally collapse a gender binary. For instance, a female reader cross-referencing the male edition (and vice-versa) generates a multiplicity of hypertextual narratives. Lexical variants for a number of entries result in even more narrative potentials. The author offers two tri-layered editions for the reader to pursue, but also a third option: multifarious lexical narratives for the reader to reconstruct in hypertext. In the lexical "triangle" that Pavić demarcates, the third metafictional option not only allows the author to privately surrender narrative authority to reading publics, but also allows the author to attain membership in reading publics by choosing his or her own lexical adventures. Through this "lexicon novel", Pavić raises questions about the purposes of sustained historicism in historical linguistics, as well as exonyms in ethnolinguistics and ethnosemiotics more broadly. Pavić also deals with the problem of identity - in his novel, the retention or loss of cultural systems has acquired importance for the fate of corresponding ethnic groups.

Structure

Contens

- Preliminary Notes

- Dictionaries (Red, Green and Yellow Book)

- Appendix I

- Appendix II

- Closing Note

At the beginning of the novel there is a shocking epigram: Here lies the reader who will never open this book. He is forever dead.'

The preliminary notes provide information about the work - the work is a reconstruction of Daubmannus's 1691 edition, the writer reveals the subject of the work (Khazar polemic), its history, explains the structure of the dictionary and how it is used. This section also provides excerpts from the preface to the first destroyed edition (Daubmannus's edition). This documentary quality is only apparent (pseudo-document, false document). Daubmanнus did exist and published a Polish-Latin Dictionary, but not the one the novelist refers to.

Searching for a lost or destroyed text, letter, or book is a familiar practice among modern writers. In addition to the first edition of the Khazar Dictionary, the novel also searches for the Khazar Sermons of Constantine of Thessaloniki - Cyril (20th century)

Playing with authorship - the question of the authorship of the Dictionary of the Khazars - was it Milorad Pavić or the publisher of the first edition, Johannes Daubmannus, or did Daubmannus′s Theoctist Nikolsky dictate the history of the Khazars? Maybe it was Mokaddasa Al-Safer or Princess Ateh, the authors of the first male and female copies of the Dictionary of the Khazars, or were they Dream Hunters, Avram Brankovich, Yusuf Masudi and Samuel Cohen.

The Appendix I is a confession of Father Theoctist Nikolsky, the editor of the first edition of the dictionary. It is in the form of an epistolary form, provides important information about the events and helps to better understand the novel's story.

The Аppendix II contains an excerpt from the court transcript of the murder case of Dr. Muawia in 1982, which brings the Khazar issue to the forefront.

The Closing Note especially emphasize the need for understanding for readers, since this is a book that requires a lot of time and attention.

Characters

Characters from the 7th to 11th century

- Princess Ateh – Princess of the Khazar Kaghanate ultimately punished with immortality and sexlessness. In the 1980s, it is revealed that she remained with the name Virginia Ateh.

- Mokaddasa Al-Safer – A priest in the Green book and a rabbi in the Yellow. He is a Dream Hunter with whom Ateh has an affair, causing him to be punished by the Kaghan by being hung in an iron cage above a river.

- Ibn (Abu) Haderash – A demon of the Islamic hell who, in the Yellow book, punished Ateh for helping the Hebrew representative of the Khazar polemic out-argue the other two representatives.

- Sabriel – The name of the Kaghan who staged the polemic in the Yellow book.

- Kaghan – The ruler of Khazar, assembled limbs into a second Kaghan from surviving cripples, the younger one as his heir, who was sent to Princess Ateh and then fell down dead finally in the Red book.

The first interpreter (participant in this polemic) was Constantine of Thessaloniki - Cyril, and he expounded the foundations of Christianity. The Islamic representative was Farabi Ibn Qora and the Jewish Isaac Sangari.

Characters from the 17th century

- Avram Brankovich – A Constantinople diplomat and compiler of the Christian part of the in-universe Khazar Dictionary.

- Yusuf Masudi – An Anatolian Dream Hunter and compiler of the Islamic part of the Khazar Dictionary.

- Samuel Cohen – A Croatian Jew and compiler of the Judaic part of the Khazar Dictionary.

- Nikon Sevast – The first name mentioned to have been used by Satan during his time on Earth. He was a calligrapher and accompanied Brankovich and Masudi on their journeys.

- Skila Averkie – A fencing instructor with whom Brankovich practiced his saber skills.

- Petkutin Brankovich – Avram Brankovich's youngest son, artificially made out of mud as an experiment to see if the dead can be tricked into thinking that someone like Petkutin could be a real human.

- Kalina – Petkutin's lover and wife. She was killed and eaten by the dead inhabitants of a Roman theatre ruin, and then killed and ate Petkutin herself.

- Yabir Ibn Akshany – The second name mentioned to have been used by Satan, after Turkish soldiers "slashed Nikon Sevast to pieces."

Characters from the 20th century

- Mr. Van der Spaak – The third name mentioned to have been used by Satan, after, as Yabir Ibn Akshany in the 17th century, he dipped his head into a pail of water, and pulled it out of a sink in a hotel in 1982.

- Dr. Isailo Suk – A Serbian archeologist and Arabist whom Mr. Spaak smothers to death with a pillow.

- Dr. Abu Kabir Muawia – A professor and Hebraist. He fought in the Israeli-Egyptian war.

- Dr. Dorothea Schultz – A professor and Slavist. She was sentenced to six years imprisonment for the false confession of killing Dr. Suk, after being blamed for the killing of Dr. Muawia, whom she intended to kill, but did not, as he provided to her an important academic discovery.

- Manuil Van der Spaak – Mr. Spaak's 4-year-old son. He shot and killed Mr. Muawia with Dr. Schultz's pistol, according to Ateh's testimony in Dr. Muawia's murder case.

- The Hungarian – A harpsichordist and keeper of the shop in which Dr. Suk bought a cello for his niece.

Reviews and reassessments

Reassessments of the book, beginning in 1997, fractured into three overlapping debates. First, a number of literary scholars contend that the deaths of the "dreamers" prior to meeting each other stemmed from Pavić's belief that semantic domains should be relegated to the world of "dreams" and not allowed to expand into the "flesh of reality." But the initial critical assessment has been countered by research into a 1988 reversal in Pavić's private and public comments on the topic. This research was then followed by further analyses of passages from the "lexicon novel" on the roles of critics and reviewers in the "triangle", exploring the possibility that the critical vanguard had overlooked or otherwise not completely assessed the book. These scholars pointed to a litany of metonyms, metaphors, allegories, semiotics of death, paratext, and structural elements of the post-structural lexicon to evince these appraisals. The inaugural critical assessments and the counter-analyses remain locked in "tension".[10] In 1996, critics who still praised Pavić's book began to publicly criticize Han Shaogong, the author of A Dictionary of Maqiao, for imitating Dictionary of the Khazars. Shaogong successfully sued these critics for defamation.[11]

A second debate pivoted on what the novel "can tell us about the ethics of translation across national boundaries?" The book was first published in Serbian Cyrillic script for the Serbo-Croatian language, excepting a Serbo-Croatian quotation printed in Serbian Latin at the end of the "lexical novel". An early wave of reviewers, and present-day reaffirmations of the same, described the third layer as composed of manifold hypertextual narratives, spawned by three scholarly efforts to reconstruct a 1691 Hebrew lexicon for the Khazar language. Critics interpreted these reconstructive traces in lexical entries as allegories for the reconstitution of suppressed and fragmented ethnic identities. After 1988, however, another set of critics found that Pavić had the book published in Serbian Latin script only. The reconstructive traces in the third layer of the 1691 lexicon, in both the Hebrew language and script, transformed into allegories for the reconstitution of a Serbo-Croatian language only in Serbian Latin script. The absence of Serbian Cyrillic, historically conjoined to Croatian Cyrillic script, rendered not only the Latin and Cyrillic designations as obsolete, but also distinctions between the Serbo-Croatian language and the script that it was published in. Pavić referred to subsequent printings as "translated" into an ascendant language paralleling Hebrew: Romanized Serbian, denoting both language and script. This "translation" (or transliteration) into Romanized Serbian then became a template for post-1988 international translations. With "Translated from the Serbo-Croatian" now signifying a translation from Romanized Serbian, the notion that disaggregation of significations was the "postmodern" version of "ethics", in comparison to the "modern" imposition of "unethical" aggregations, itself came to rest on a strict dichotomy.[12]

In the last debate, a set of literary critics evaluated the third side of Pavić's "triangle" as both replacing and sustaining a "modern narrative totality" with the "idea of a 'totality,' which Pavic's text elucidates in passages that betray a dose of latent nationalism, [that] is the recognition of the unified national being." This "postmodern fragmentation" underpinned post-structural representations of social structure for the Serbian nation-state in law, policy, and political economy. Yet another set of critics concurred that an aim and impact of Serbian "postmodern literature" was indeed "national definition through postmodern fragmentation...that ultimately facilitated the appearance on the formerly Yugoslav cultural scene in the 1990s of a whole generation of Postmodernists who expressed genealogical interest in national history." But these analysts refused to rush to that same conclusion for translators and reading publics of the book in additional nation-states. Yugoslav and Serbian cultural circumstances were requisites for the "lexical novel" to become a "narrative totality", rather than innate to its "postmodern" genre. The goals of Serbian "postmodern fragmentation" were not additional lines of evidence for the book promulgating another "narrative totality...the narrative is not atomized for the sake of meaningless destruction, but for the purpose of (re)creating a new and arguably more unified body/narrative." Instead, the goals were the cultural preconditions for such a totality. Despite the introduction of a publication template in Romanized Serbian, the linguistic mobility of the "lexicon novel" in multicultural translations challenged "modern narrative totality" without imposing its own "postmodern narrative totality" on international readers. The elseworlds of cultural relativism served as premises for this rejoinder.[13]

See also

References

- ^ Milorad Pavić's official site: TRANSLATIONS Archived March 22, 2010, at the Wayback Machine (in Serbian)

- ^ Lektire i puškice: Hazarski rečnik – Milorad Pavić (in Serbian)

- ^ Milorad Pavić's Dictionary of the Khazars, New York: Knopf, 1988

- ^ the male and female versions

- ^ He Thinks The Way We Dream, by D. J. R. Bruckner

- ^ "HAZARSKI REČNIK – Lovci na snove | Opera & Theatre Madlenianum". operatheatremadlenianum.com. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- ^ Pavić, Milorad (1988). Dictionary of the Khazars: A Lexicon Novel in 100,000 words (1st American, Male ed.). New York: Knopf : Distributed by Random House. pp. 11–14. ISBN 9780394571836.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - ^ Viorica, Cazac (2022). "Rhombus: Meanings and Interpretations". IV Міжнародна науково-практична конференція «АКТУАЛЬНІ ПРОБЛЕМИ СУЧАСНОГО ДИЗАЙНУ» Київ, КНУТД, 27 квітня 2022 р. (PDF). Kyiv National University of Technologies and Design. pp. 11–13.

- ^ Pavić, Milorad (1988). Dictionary of the Khazars: A Lexicon Novel in 100,000 words (1st American, Male ed.). New York: Knopf : Distributed by Random House. pp. 14–15. ISBN 9780394571836.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - ^ Freise, Matthias (2018). "Four Perspectives on World Literature: Reader, Producer, Text and System". Tensions in World Literature: Between the Local and the Universal. Springer Singapore : Imprint: Palgrave Macmillan: 196–200.

- ^ Iovene, Paola (2002). "Authenticity, Postmodernity, and Translation: The Debates around Han Shaogong's Dictionary of Maqiao" (PDF). AION. 62 (1–4): 1–21.

- ^ Bermann, Sandra; Wood, Michael; Damrosch, David (July 25, 2005). "Death in Translation". Nation, Language, and the Ethics of Translation. Princeton University Press: 380–398.

- ^ Aleksić, Tatjana (2009). "National Definition Through Postmodern Fragmentation: Milorad Pavić's Dictionary of the Khazars". The Slavic and East European Journal. 53 (1): 86–104. ISSN 0037-6752. JSTOR 40651071.

External links

- Dictionary of the Khazars: a novel by Milorad Pavic, excerpts from "Postmodernism as Nightmare: Milorad Pavic's Literary Demolition of Yugoslavia" by Andrew Wachtel

- Pavić′s Writing Slope Box (In Serbian) RTS - Official channel