Cuckfield Park

| Cuckfield Park | |

|---|---|

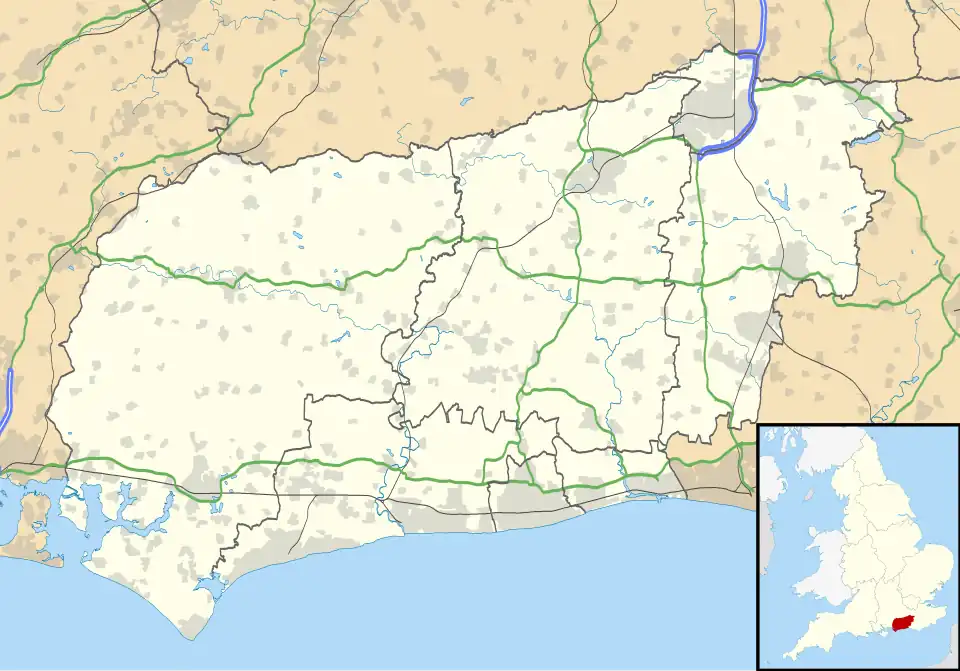

Location of Cuckfield Park in West Sussex | |

| Type | Country house |

| Location | Cuckfield |

| Coordinates | 51°00′16″N 0°09′07″W / 51.00444°N 0.15194°W |

| OS grid reference | TQ 29755 24416 |

| Area | West Sussex |

| Built | 1574 |

| Architectural style(s) | Elizabethan |

| Owner | Bryan Mayou and Susan Mayou |

Listed Building – Grade II* | |

| Official name | Cuckfield Park |

| Designated | 10 September 1951 |

| Reference no. | 1025541 |

Cuckfield Park is a Grade II* listed Elizabethan House and parkland in the village of Cuckfield in West Sussex, England.[1]

History

In 1573, the site, originally a deer park, was bought by Henry Bowyer, a local ironmonger, and his wife, Elizabeth Vaux, daughter of the Comptroller of the Household Clerk Comptroller of Henry VIII’s household, from the 4th Earl of Derby.[2][3] They then built the manor house, which was completed in 1574.[4] Henry and Elizabeth’s initials, and the date, 1574, can still be seen on the stone chimney piece in the dining room.[5]

The 192-acre surrounding parkland was opened in 1618 when it was no longer restricted for the use of deer.[6]

Cuckfield Park has an especially well-documented history and is often referred to in the Sergison Papers, which are held in the West Sussex County Council Record Office.[7] A comprehensive history of the village of Cuckfield was published in 1912, written by Canon Cooper, a vicar of Cuckfield from 1888 until 1909, and the Chairman of the Sussex Archaeological Society.[8] This included a comprehensive account of Cuckfield Park, which was featured in the magazine Country Life in March 1919.[9]

Since 1981, the Cuckfield Cricket Club, Sussex Premier League Champions, 2023, have played at Cuckfield Park.[10][11]

An annual bonfire is held at Cuckfield Park to mark Bonfire Night.[12][13]

Architecture

The existing, stucco-faced manor house, built in 1574, replaced a medieval manor hall which Henry Bowyer and Elizabeth Vaux dismantled.[14]

The gatehouse was built a few years later, possibly including stone obtained from the original house.[15] A long avenue of lime trees lines the drive which leads up to the house.[16]

The house has had many additions over the years. In the late 17th century, the western side of the house was extended, and the south front was created between 1849 and 1851.[17]

Inside the house, there are a number of significant features. The drawing room features a fireplace designed by Anglo-Dutch sculptor Grinling Gibbons, and the stone chimney in the dining room holds the initials of Henry Bowyer and Elizabeth Vaux, along with the date the building was created, 1574.[18][19] Additionally, the entrance hall has an Elizabethan carved wooden screen, mentioned in the Encyclopædia Britannica as an example of an early Renaissance screen.[20]

The house has been described in several books, including Pevsner’s The Buildings of England, The Historic Houses of Sussex by Viscountess Wolseley (2009) and Historic Houses of West Sussex and Their Owners by Frances Garnett (2009).[21][22][23]

In literature

William Harrison Ainsworth/Dick Turpin

Cuckfield Park was the inspiration for William Harrison Ainsworth’s 1834 Victorian gothic romance novel, Rookwood. In Rookwood, Ainsworth invented the legend of Dick Turpin’s ride from London to York. In the preface to Rookwood, Ainsworth discusses Cuckfield Place and the family living there:

‘The supernatural occurrence, forming the groundwork of one of the ballads which Cuckfield Place, to which this singular piece of timber is attached, is, I may state, for the benefit of the curious, the real Rockwood Hall; for I have not drawn upon imagination, but upon memory, in describing the seat and domains of that fated family. The general features of the venerable structure, several of its chambers, the old garden, and, in particular, the noble park, with its spreading prospects, its picturesque views of the Hall, its deep glades, through which the deer come lightly tripping down, its uplands, slopes, brooks, brakes, coverts, and groves, are carefully delineated.’

Percy Bysshe Shelley

English Romantic poet, Percy Bysshe Shelley regularly visited Cuckfield Park when visiting his uncle, who lived in the village of Cuckfield. He described the house and park, which “abounded in ‘bits of Mrs Radcliffe’” in reference to the gothic settings of the novelist Ann Radcliffe.[24][25]

Zadie Smith

In her 2023 novel The Fraud, Zadie Smith wrote a chapter titled ‘Cuckfield Park’, describing the fictionalised place as “Cuckfield Park, a gloomy Elizabethan mansion in Sussex”.[26][27][28]

Folklore

There are a number of paranormal and folk tales connected to Cuckfield Park.

The Tree of Doom

Described in the novel, Rookwood, a folk story suggests that when a member of the family who owns Cuckfield Park dies, a self-amputating tree in the grounds will drop one of its branches.

“…gigantic lime, with mighty arms and huge girth of trunk, as described in the song) is still carefully preserved. I have made the harbinger of doom to the house of Rookwood, is ascribed, by popular superstition, to a family resident in Sussex; upon whose estate the fatal tree (a gigantic lime, with mighty arms and huge girth of trunk, as described in the song) is still carefully preserved.”

Gatehouse Dead

A custom of the second owners of Cuckfield Park, the Sergisons, was to place their dead in the Gatehouse. At midnight, the cortege would leave for the burial as the Gatehouse clock struck. This tradition was discontinued in 1914.[29]

Wicked Dame Sergison

The house is said to be haunted by former resident, Anne Pritchard Sergison, known as Wicked Dame Sergison. She was said to have attended her granddaughter’s wedding after her death in 1848, and haunted passing horses from the oak gates to the Park.[30][31]

The vicar and curate of Cuckfield held a service of exorcism in the village church and drowned the ghost in the font. Anne Pritchard Sergison’s son replaced the oak gates with spiked iron gates, seemingly stopping the haunting.[32][33]

Notable inhabitants

Several families have lived at Cuckfield Park. The estate remained in the ownership of the Bowyer family for over 115 years until the house was sold to Charles Sergison in 1699. Sergison was a successor to Samuel Pepys as Clerk of the Acts and a British Navy Commissioner, head of civil administration of the Navy, a position he held for over 30 years.[34]

Sergison’s naval records, known as The Sergison Papers, were published by the Naval Record Society in 1950, and include his state of the Navy report requested by William of Orange. The papers are on display at the United States Naval Academy Museum.[35][36] Charles Sergison’s model ships were kept at Cuckfield Park and later loaned to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City.[37][38][39]

For many years, the estate was passed through the Nevill family after a peerage was granted to George Nevill, 1st Earl of Abergavenny, in 1744.[40] Other families who have owned the estate include the Coverts of Slaugham, the Henleys, and the Sergisons.[41] Since 1900, Cuckfield Park has been through several changes of ownership.[42][43]

Plastic surgeon, Bryan Mayou, and his wife, dermatologist Susan Mayou, have lived at Cuckfield Park since 2004.[44]

References

- ^ "CUCKFIELD PARK, Cuckfield - 1025541 | Historic England".

- ^ "Is there a tunnel across Cuckfield Park? (2)". 28 March 2022.

- ^ https://www.cuckfield.org/page.php?pg=37

- ^ https://www.cuckfield.org/page.php?pg=37

- ^ https://www.cuckfield.org/page.php?pg=37

- ^ https://www.parksandgardens.org/places/cuckfield-park

- ^ https://www.parksandgardens.org/places/cuckfield-park

- ^ "1909: Distinquished Cuckfield historian and vicar dies". 14 December 2021.

- ^ "1919: Country Life and Cuckfield Park". 24 March 2022.

- ^ "Cuckfield CC: History".

- ^ "Watch Cricket at Cuckfield online - BFI Player".

- ^ "Location - CUCKFIELD PARK".

- ^ "Sussex prepares for bonfire night celebrations". November 2024.

- ^ https://www.cuckfield.org/page.php?pg=37

- ^ https://www.parksandgardens.org/places/cuckfield-park

- ^ "1971: In celebration of Cuckfield Park, built 400 years ago". 23 March 2021.

- ^ "Heritage Gateway - Results".

- ^ https://www.parksandgardens.org/places/cuckfield-park

- ^ "1971: In celebration of Cuckfield Park, built 400 years ago". 23 March 2021.

- ^ "1971: In celebration of Cuckfield Park, built 400 years ago". 23 March 2021.

- ^ "1928 - A guided tour of Cuckfield Place". 5 June 2020.

- ^ Westwood, Jennifer; Simpson, Jacqueline (2 October 2008). The Penguin Book of Ghosts: Haunted England. Penguin Adult. ISBN 978-1-84614-101-0.

- ^ Paranormal Sussex. Amberley Publishing Limited. 15 October 2009. ISBN 978-1-4456-3014-4.

- ^ "Highways and Byways in Sussex/Chapter 22 - Wikisource, the free online library".

- ^ "1928 - A guided tour of Cuckfield Place". 5 June 2020.

- ^ https://languagehat.com/talking-cant/

- ^ Chakraborty, Abhrajyoti (27 August 2023). "The Fraud by Zadie Smith review – a trial and no errors". The Guardian.

- ^ https://www.enotes.com/topics/the-fraud/chapter-summaries

- ^ "1971: In celebration of Cuckfield Park, built 400 years ago". 23 March 2021.

- ^ "Cuckfield Park – Susana's Parlour".

- ^ http://www.greatbritishghosttour.co.uk/Pages/England/West%20Sussex/Cuckfield.html

- ^ Westwood, Jennifer; Simpson, Jacqueline (2 October 2008). The Penguin Book of Ghosts: Haunted England. Penguin Adult. ISBN 978-1-84614-101-0.

- ^ Paranormal Sussex. Amberley Publishing Limited. 15 October 2009. ISBN 978-1-4456-3014-4.

- ^ https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1690-1715/member/sergison-charles-1655-1732

- ^ "1971: In celebration of Cuckfield Park, built 400 years ago". 23 March 2021.

- ^ "The Sergison Papers, 1688-1702 – the Navy Records Society".

- ^ "The Ship Models at Cuckfield Park, Sussex". 2 February 1911.

- ^ Laughton, John Knox (1897). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 51. p. 254.

- ^ Culver, Henry B. (1923). "The Cuckfield Park Models Lent by Colonel H. H. Rogers". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. 18 (7): 168–173. doi:10.2307/3254717. JSTOR 3254717.

- ^ https://www.parksandgardens.org/places/cuckfield-park

- ^ https://www.parksandgardens.org/places/cuckfield-park

- ^ https://www.parksandgardens.org/places/cuckfield-park

- ^ "1971: In celebration of Cuckfield Park, built 400 years ago". 23 March 2021.

- ^ https://www.visitbrighton.com/whats-on/christmas-evening-at-cuckfield-park-p2464321