Colleges within universities in the United Kingdom

Colleges within universities in the United Kingdom can be divided into two broad categories: those in federal universities such as the University of London, which are primarily teaching institutions joined in a federation, and residential colleges in universities following (to a greater or lesser extent) the traditional collegiate pattern of Oxford and Cambridge, which may have academic responsibilities but are primarily residential and social. The legal status of colleges varies widely, both with regard to their corporate status and their status as educational bodies. London colleges are all considered 'recognised bodies' with the power to confer University of London degrees and, in many cases, their own degrees. Colleges of Oxford, Cambridge, Durham and the University of the Highlands and Islands (UHI) are listed bodies, as "bodies that appear to the Secretary of State to be constituent colleges, schools, halls or other institutions of a university".[1] Colleges of the plate glass universities of Kent, Lancaster and York, along with those of the University of Roehampton and the University of the Arts London do not have this legal recognition. Colleges of Oxford (with three exceptions), Cambridge, London, and UHI, and the recognised colleges of Durham, are separate corporations, while the colleges of other universities, the maintained colleges of Durham, and the societies of the university at Oxford are parts of their parent universities and do not have independent corporate existence.

In the past, many of what are now British universities with their own degree-awarding powers were colleges which had their degrees awarded by either a federal university (such as Cardiff University) or validated by another university (for example many of the post-1992 universities). Colleges that had (or have) courses validated by a university are not normally considered to be colleges of that university; similarly the redbrick universities that, as university colleges, prepared students for University of London external degrees were not considered colleges of that university. Some universities (e.g. Cardiff University) refer to their academic faculties as "colleges";[2] such purely academic subdivisions are not within the scope of this article.

Traditional collegiate universities

Historical development

Ancient and early modern colleges

The two ancient universities of England, Oxford and Cambridge (collectively termed Oxbridge), both became organised as universities in the early 13th century, prior to the founding of the first colleges.[3] The idea of colleges was imported to England by William of Durham from the University of Paris, where colleges had existed since the foundation of the Collège des Dix-Huit in 1180, who left money to establish University College, Oxford in 1149.[4][5] The first college at Cambridge, Peterhouse, followed in 1284.[6] These early colleges were residential institutions for postgraduates; teaching in colleges, another innovation imported from Paris (pioneered by the College of Navarre in 1305), arrived in England with the establishment of New College, Oxford in 1379, also the first English college to admit undergraduates.[4][7] However, throughout the Middle Ages only a minority of studentsat Oxford and Cambridge – estimated to be between 10 and 20 per cent – were members of colleges.[3]

By the time of Queen Elizabeth I, the statutes of Cambridge University implied that every student was a member of a college.[8] At around the same time, the heads of the Oxford colleges gained their first statutory power under the chancellorship of Robert Dudley.[9]

The importance of the colleges continued to grow, with the Hebdomadal Board (of college heads) being set up by Archbishop William Laud as chancellor of Oxford University in 1631, in order to reduce the power of congregation and convocation.[10] The Laudian Code of 1636 also made it obligatory for students at Oxford to join a college or hall.[11]

19th century innovation and reform

The ancient universities thus evolved into federations of autonomous colleges, with a small central university body, rather than universities in the common sense. This led to calls for reform in the 19th century, with speeches in the House of Commons saying that the "colleges [had] usurped the legislative functions of the universities",[12] while Sir William Hamilton wrote of Oxford that, due to the teaching being carried out by college tutors rather than university professors, "The University is in abeyance... In none of its faculties is it supposed that the professors furnish any longer the instruction necessary for a degree. ... It is not even pretended that Oxford now applies more than the preliminary of an academical education. Even this is not afforded by the University, but abandoned to the Colleges and Halls; and the Academy of Oxford is thus not one public Universities, but merely a collection of private schools."[13]

The only university to establish a residential college system in Britain during the 19th century was Durham University, although University Hall, a quasi-collegiate hall of residence, was established in London by the Unitarians in 1849 for students at University College London, and similar quasi-collegiate halls were established in Manchester towards the end of the 19th century for students at Owens College.[14][15]

Durham University was founded in 1832, a year after Hamilton had written that article. It followed the example of Oxford and Cambridge with respect to residence (while departing significantly from it in other respects), pursuing a collegiate model from the start.[16] Two important innovations were, however, made that were later taken up for the colleges of the plate glass universities (below) and the residential colleges of US universities: Firstly, teaching was organised centrally, following the Scottish pattern, rather than in the colleges, with the colleges being residential and responsible for student discipline, as had originally been the case at Oxford and Cambridge. Charles Thorp, the first warden (head) of the university, stated that the professors "have the charge of the studies in their respective departments and work as at Glasgow and the foreign Universities, and as they did at Oxford in old times"; and while the professorial teaching was supplemented by tutorials, the tutors were under the direction of the professors, as Hamilton had proposed.[17] Secondly, the colleges at Durham were (starting with the original University College) owned by the university rather than being independent like Oxbridge colleges. This aspect of the Durham model, in particular, was later adopted for residential colleges at US universities and has been described as "a far better model for people at other institutions to look to, than are the independent colleges of Oxford and Cambridge".[18][19]

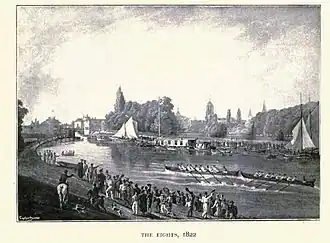

Inter-collegiate sport started with rowing at Oxford, where the first known competition was in 1815 with Brasenose College winning and Jesus College being possibly their only competitor.[20] Inter-collegiate rowing spread to Cambridge in 1827 and to Durham in 1850.[21][22] Over the course of the 19th century more sports were taken up by the colleges and competitions, including many of the cuppers at Oxford and Cambridge, were well established in sports such rugby, football, cricket, tennis and fives at all three universities by the end of the century.[23][24][25]

Whitelands College, later a college of the University of Roehampton, was founded in London in 1841 by the National Society for Promoting Religious Education as a residential teacher training college. It opened in January 1842 as the first teacher training college for women in England.[26][27]

Another innovation was introduced at Durham with the founding of Bishop Hatfield's Hall in 1846. The founding principal, David Melville, instituted a system of economy with the aim of allowing men who could not otherwise have afforded it to attend university. This has been called "arguably the single most successful and influential undertaking at Durham throughout the nineteenth century" apart from the university's foundation.[28] It relied on three innovations: rooms were let furnished, with shared servants, rather than students employing their own servants; all meals were taken in the dining hall, rather than students eating in their rooms; the price of room and board was reasonable and fixed in advance.[29] Melville also pioneered the use of single-room study-bedrooms rather than the "set" of multiple rooms previously used by students.[30] In 1848, Charles Marriott advocated that a similar hall should be established at Oxford; this eventually happened with the establishment of Keble College in 1870,[31] which would go on to inspire a similar model of economy at Selwyn College, Cambridge.[32] Melville's innovation subsequently became the standard model for residential accommodation at universities around the world.[33][34] In 1852, the Royal Commission established to look into the University of Oxford found that "The success that has attended Mr. Melville's labours in Hatfield Hall at Durham is regarded as a conclusive argument for imitating that institution in Oxford";[35] this report led to a requirement in the Oxford University Act 1854 that Oxford allow the establishment of private halls, although these halls were never very successful.[36][37] The Cambridge University Act 1856, following the recommendations of a Royal Commission looking into that university, similarly made provision for the establishment of private hostels.[38][39][40]

The main thrust of the royal commissions, however, was to curtail the power of the colleges, putting more of the governance of the universities back into the hands of their teachers. The number of professors, and the range of subjects taught, was expanded, although most undergraduate teaching remained with college lecturers.[37][40][41]

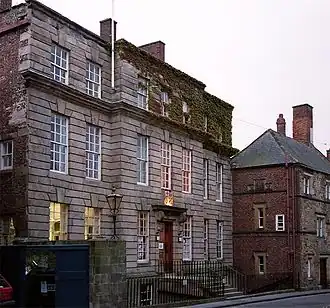

The commissions also recommended allowing students to join the universities without having to join a college. Oxford led the way, admitting non-collegiate students from 1868,[42][43][44] followed by Cambridge in 1869.[45][46] Durham, possibly influenced by Archbishop Tait who had been a strong advocate for admission of unattached students on the Oxford commission, admitted non-collegiate students over the age of 23 from 1871.[47] At Oxford, the non-collegiate students formed themselves into the Clarendon University Club, named after their meeting place. This had moved to St Catharine’s Hall by 1874, becoming known as the St Catharine’s Club.[42][43][44] The unattached men at Durham similarly organised themselves by the 1880s into a society, which became known as St Cuthbert's Society in 1888; this gained a room in Cosin's Hall as a base in 1892.[48] At Cambridge, the university bought Fitzwilliam Hall for the use of the non-collegiate students in 1887.[45][46]

The first residential college for women, Girton, was established near Cambridge in 1869,[49] followed by Newnham in 1871.[50] The first at Oxford were Somerville and Lady Margaret Hall, both founded in 1879.[51] The Society of Oxford Home-Students was formed for women not resident at a women's college in 1879,[52] although women could not matriculate at Oxford until 1920.[51] No women's colleges were established at Durham until after it received a supplemental charter in 1895 opening its degrees to women. In 1896, St Hild's College, the Diocese of Durham's teacher training college for women, was brought into connection with the university, allowing its students to take degrees.[53] Non-collegiate women were first admitted to Durham in 1897 as "home students", under their own censor, but numbers never rose above ten until after the second world war and no society was established until 1947.[54] The Women's Hostel was established in 1899 and formally became a college in 1919, changing its name to St Mary's College.[55] Four women's colleges at Oxford received royal charters and formally became colleges of the university in 1926, although they would not be given full college status until 1959.[56] At Cambridge, Newnham received a royal charter in 1917 and Girton in 1924 but they were not recognised as colleges of the university until 1948.[57][58]

20th century development

Following the first world war, the University Grants Committee was established in 1919 to fund universities. Oxford and Cambridge did not receive funding until after the royal commission into both universities in 1922 but when they were approved to receive funding it was paid to the universities rather than to the colleges, shifting the financial balance towards the central administration.[59] Oxford replaced the status of private hall with that of permanent private hall in 1918,[60] and Cambridge replaced public hostels with approved foundations in 1926.[61] Oxford also redefined its non-collegiate students as "societies". The non-collegiate men were formed into St Catherine's Society in 1931, based on the St Catharine's Club the students had established earlier,[42][43] while the non-collegiate women in the Society of Home Students became St Anne's Society in 1942.[62]

An increase in funding for students after the second world war made university education more affordable, undermining the rationale behind opening up the universities to non-collegiate students and leading to almost all of the non-collegiate bodies beginning colleges in the 1950s and 1960s.[45] At Oxford, the two societies became St Anne's College and St Catherine's College in 1952 and 1963 respectively.[42][43][63] At Cambridge, the decision was made as early as 1944 to develop Fitzwilliam House (as it had been renamed in 1924) into a college, with this being accomplished by 1966.[45] At Durham, the non-collegiate students were organised into two recognised societies in 1947, each under a principal: St Aidan's Society for women, which went on to become St Aidan's College in 1961,[54] and St Cuthbert's Society – already organised by the students themselves in 1888 but now brought under the control of the university – for men.[64] St Cuthbert's Society was an exception in that it did not become a college in the 1950s or 1960s, although it accreted accommodation from 1951 onwards.[48]

The first postgraduate-only college, and the first mixed college, was Nuffield College, established at Oxford in 1937, although it did not open until 1945 due to the war. It was also the first specialist college, specialising in the social sciences.[65] After the war, the next postgraduate college founded was St Antony's College, Oxford, in 1950, specialising in area studies.[66] Postgraduate colleges flourished in the 1960s, with four founded in Oxford (three initially owned by the university, although two of these latter gained royal charters, and a specialist centre for management studies),[67][68][69][70] three at Cambridge (starting with Darwin College in 1964, also Cambridge's first mixed college; two were established by existing colleges and one by the central university),[71][72][73][74] and one at Durham (the Graduate Society in 1965, also Durham's first mixed college).[75]

The post-war period also saw the establishment of new undergraduate colleges for men and women at Cambridge and Durham. This also saw debates in both universities about whether the new men's colleges of the 1950s should specialise in science and technology: these were the drivers of the university expansion, with the University Grants Committee insisting until 1967 that two thirds of new student places should be in these fields.[76] There had already been debate about the merits of specialist colleges following the establishment of Nuffield College in Oxford, where this – rather than it being mixed or involving non-academics in its work – was said to have "proved particularly unpopular" among more conservative academics.[77] For both Grey College, Durham, (opened 1959) and Churchill College, Cambridge, (opened 1961) the decisions were to retain a full subject mix, although Churchill was permitted to be weighted towards science and technology, with 70% of its students in those fields, while Grey took an approximately equal split of science and arts students.[78][79]

Three of the seven plateglass universities established as part of the expansion of universities in the 1960s adopted residential college systems, while the others built non-collegiate halls of residence. Collegiate systems survive in two of these, Lancaster and York, while Kent moved away from the collegiate system (see § Former collegiate universities below). The plate-glass universities followed Durham in creating colleges that were part of the university, rather than independent foundations, and that were not directly involved in teaching.[80]

The colleges of the plateglass universities were mixed from their foundation, before any of the undergraduate colleges of the older universities. The first colleges established were at Lancaster, where Bowland and Lonsdale were founded alongside the university in 1964. However, although students were assigned to the colleges, the first college residential buildings did not open until 1968.[81] 1965 saw the first actually co-residential undergraduate colleges open, with the two founding colleges at York (Langwith and Derwent) as well as Eliot College, Kent.[82][83][84][85]

The first undergraduate collegiate body to become mixed at the older universities was the still primarily non-residential St Cuthbert's Society, Durham, in 1969.[86] It was not until the age of majority was reduced from 21 to 18 in 1970, and the universities ceased to be in loco parentis, that the undergraduate residential colleges began to become mixed.[87] In 1972, two men's colleges at Cambridge and one at Durham became mixed,[88][89] and Collingwood College, Durham, opened as the first mixed undergraduate college founded at the older universities and the first British university residence to have mixed-sex corridors.[90] The first five undergraduate colleges at Oxford became mixed in 1974.[91] The only undergraduate college to have been founded as mixed at either Oxford or Cambridge was Robinson College, Cambridge, which opened in 1981.[92][93]

The first women's college to go mixed was Girton, which admitted men to its fellowships in 1977, as postgraduates in 1978, and as undergraduates in 1979.[94] The last all-male colleges at Oxford (excluding permanent private halls) went mixed in 1986,[95][96] and the last at Cambridge and Durham in 1988.[97][98][99][100]

Reforms of teacher training in the 1970s caused disruption for teacher training colleges, many of which ended up meeting o'r being absorbed by universities.[101] This affected three independent colleges at Durham, two of which merged and then joined the university to become a maintained college,[102] while the third left the university in 1977 to merge with another college.[103] The changes also caused four teacher training colleges in south west London to federate as the Roehampton Institute of Higher Education, but preserving the individual characters of the four colleges.[104]

21st century

The Roehampton Institute of Higher Education became part of the Federal University of Surrey in 2000, and then became an independent, collegiate university in 2004 as Roehampton University.[104]

The first decade of the 21st century saw the remaining women's colleges at Oxford and Durham become mixed. The last women's college in Durham, St Mary's, became mixed in 2005,[105] while the last ar Oxford, St Hilda's, became mixed in 2008.[106] As of 2025, there were two remaining women's colleges at Cambridge: Murray Edwards and Newnham. The last institution at Oxford to become mixed was St Benet's Hall (closed 2022), a permanent private hall rather than a college, which admitted postgraduate women from 2014 and undergraduates from 2016.[106][107]

Durham shifted its two remaining societies to being colleges in the first decade of the century, ending over a century of (formally) non-collegiate students at the university. The Graduate Society became Ustinov College in 2003 and moved to newly built accommodation in 2005.[108] St Cuthbert's Society then took over the former buildings of Ustinov College in 2006.[109] The university agreed in 2008 that St Cuthbert's could keep the title of "society" in honour of is heritage.[48]

Colleges continued to be established, with (as of 2025) four new foundations at York, the same number at Durham, and a new (university owned) postgraduate college at Oxford. Two existing colleges also moved to newly constructed sites at Lancaster, as did two at York, allowing the universities to expand. The 21st century saw a move away from college catering towards self-catering, with all of the new colleges being self-catered.[110][111][112]

By 2010, Kent had decided that it "could no longer sustain its traditional commitment to its original collegiate foundations".[113] The position of college master was abolished at Kent in 2020,[114] and the university's ordinances were revised in 2025 to remove mention of colleges.[115][116] York also abolished the post of principal at its colleges in 2023, but retained college councils, now chaired by the senior fellow of the college.[117]

Universities

University of Oxford

The University of Oxford has 36 colleges with their own royal charter, three societies owned by the university, and four permanent private halls owned by Christian denominations, all of which are generally referred to as "colleges".[118] While most colleges at Oxford are independent corporations, the three societies (Kellogg College, St Cross College, and Reuben College) are established and maintained by the central university;[119] the newest, Reuben College, was formally established in 2019 and admitted its first students in 2021.[120][121]

Undergraduates are accepted by 30 of the chartered colleges and two of the permanent private halls. One of the 30 colleges, Harris Manchester College, only takes mature students (21 and over).[118][122] Postgraduates are accepted by 36 of the chartered colleges, including five postgraduate-only colleges, the three societies, which are all postgraduate-only, and the four permanent private hairs, two of which are postgraduate-only.[123] One college, Ail Souls College, is an academic research institute that does not accept students.[124] Undergraduate admissions are formally carried out by colleges, but there is a centralised screening process to decide which applicants to interview and the university has suggested that "in many cases final decisions about who to accept will be taken by departments".[125]

University of Cambridge

There are 31 colleges at the University of Cambridge, all of which are independent corporations with their own royal charter. The university statutes also allow for "approved foundations" and "approved societies", but there are not currently any colleges in these categories.[126] Academic faculties and departments are responsible for lectures, seminars and practical classes.[127]

Cambridge colleges have more autonomy in undergraduate admissions than their counterparts at Oxford, and most applicants will be interviewed.[125] Two of the colleges only admit postgraduates while a further three only take postgraduates and mature undergraduates.[122] Of the remaining 26 that take undergraduates of all ages, two are women's colleges while the others are open.

Durham University

The colleges of Durham University hold the same legal status of 'listed bodies' as the colleges of Oxford and Cambridge, although they do not play the same role in the selection of undergraduate students or teaching.[80] Durham's colleges are (with two exceptions) owned by the university. The collegiate nature of the university is explicitly defined in the university's statutes, which can only be modified with permission of the King in Council, with further details defined in the ordinances.[128][129]

Most colleges at Durham are "maintained colleges" owned by the university. However, there are two independent "recognised colleges", St Chad's and St John's, which are separate legal entities. These operate as colleges of the university under memoranda of understanding that are reviewed every five years.[130] While university teaching is not carried out in any of the colleges, St John's College has teaching in Cranmer Hall, a Church of England theological college;[131] St Chad's College also trained Anglican priests until 1971.[132]

All colleges have a student common room (normally known as the JCR), which is mandated by the university's statutes, and offer college sports and social spaces. Many colleges have libraries and some colleges have chapels or multi-faith rooms. Colleges may be catered or self-catered, but all hold formal meals, for which gowns are worn in most colleges.[133][134][135][136][137] Each college also has a head of college, who is an ex officio member of the university's senate.[138] The head of college is appointed by the university's council.[139]

Undergraduate applicants who receive an offer from Durham are given the opportunity to rank their college choice. They are then allocated to colleges using an algorithm that tries to balance home and overseas students and the number of students from different departments while taking into account the students' preferences (if they have supplied a ranking). Final colleges are confirmed after A-level results are released.[140][141]

Since 2020, there have been 17 colleges in Durham city (one, Ustinov, postgraduate only): the 5 Bailey colleges located on the historic peninsula, which are usually thought of as being more traditional; the 10 Hill colleges on Elvet Hill, near the Mountjoy site on the south side of Durham; Ustinov College in Neville's Cross; and the College of St Hild and St Bede (Hild Bede), temporarily located in Rushford Court to the west of the city centre while its Leazes Road site on the north bank of the Wear is renovated.[142][143][144] Two colleges previously based at the Queen's Campus in Stockton-on-Tees relocated to Durham over 2017–2018, and the 17th college, South College, opened in September 2020.[144][145][146] Once the renovations to Hild Bede are complete, it is planned that Rushford Court will become Durham's 18th college, while a 19th college will be constructed next to Hild Bede on the Leazes Road site..[143][147]

Lancaster University

The University of Lancaster is defined by its royal charter to be a collegiate university.[148] It has nine colleges, eight of which are for undergraduate students and one – Graduate College – which is for postgraduate students. The undergraduate colleges consist of: Bowland; Cartmel; County; Furness; Fylde; Grizedale; Lonsdale and Pendle, all of which have their own bars with different themes.[149] The undergraduate colleges were founded between 1964 (when the university was established) and 1974, with Graduate College being added in 1992.

All students and staff at Lancaster are college members.[150] Colleges are independent of university education, instead providing on-campus accommodation, social events and sporting teams.[151] Undergraduate students must choose from one of the eight undergraduate colleges; on-campus accommodation is usually a key factor in this choice.[152] Postgraduate students are always assigned to Graduate College, whereas staff members may choose any college. Students must pay a college membership fee.[153] There is a programme of inter-college sports, with the winner being awarded the Carter Shield.[154]

University of York

There are eleven colleges at the University of York, with the most recent founded in 2022, and all students are members of a college.[155][156][157] One college, Wentworth Graduate College, is postgraduate only.[158] Each college is governed by its own college council, which contains a combination of university staff and elected student members and is chaired by a senior college fellow (the role of college principal having been abolished in 2023), and is managed by a college manager.[117][156] Most colleges have a Junior Common Room for undergraduate students, which is managed by the elected Junior Common Room Committee. Some colleges retain a Graduate Common Room for postgraduate students, as well as a Senior Common Room, which is managed by elected representatives of the college's academic and administrative members. Other colleges however combine undergraduate and postgraduate representation together into student associations.[159]

Intercollegiate sport is one of the main activities of the colleges. Currently there are 21 leagues with weekly fixtures, in addition a number of one day events are organised as well.[160] In 2014 the "College Varsity" tournament was created, with sporting competitions held between York's colleges and the colleges of Durham University. York hosted the first tournament which was won by Durham's colleges; the second tournament was hosted by Durham in 2015, who won again. The third tournament was held in York in 2016, with York winning for the first time, and the fourth in Durham in 2017, with the hosts reclaiming the title.[161][162][163]

University of Roehampton

The University of Roehampton has its roots in the traditions of its four constituent colleges – Digby Stuart, Froebel, Southlands and Whitelands – which were all formed in the 19th century. Each college has a "providing body", an independent charity that owns the freehold or leasehold interest of the college's property.[164] The university holds long-term leases and management agreements with the providing bodies for three of the colleges, and a rolling seven-year licensed and management agreement for Whitelands. While the colleges were all originally independent, they have now merged into the university, with the last college (Whitelands) merging in 2012.[165]

Each college has an elected president and vice-president. These, among with the university-wife sabbatical president and two sabbatical vice-presidents, make up the elected officers of Roehampton Students' Union.[166]

Former collegiate universities

University of Kent

All students at the University of Kent were part of one of eight colleges. Each college had a master, who was responsible for enforcing University regulations and ensuring safe student conduct. Each college also had an elected student committee. There were seven colleges (Eliot, Rutherford, Keynes, Darwin, Turing, Park Wood, and Woolf) on the Canterbury campus, with Woolf being "mainly postgraduate", and Medway College on the Medway campus.[167] The initial four colleges (Elliot, Rutherford, Keynes and Darwin) were established between 1965 and 1970, after which no new college was established at the Canterbury campus until Woolf in 2008. This was followed by Turing (2014) and Park Wood (2020).[168] The university abolished the position of college master in 2020.[114] Following this, a revision of the university's ordinances in June 2025 deleted the section on colleges that had been present up to the 2024 revision, removing then from the university's constitutional documents.[115][116] As of 2025, only three of the university's residences still bear the names of colleges.[169]

Federal systems

Fully federal universities

University of London

The University of London is a federal university comprising 17 member institutions. Following the passing of the University of London Act 2018, constituent colleges could apply to become universities in their own right while remaining members of the federal university; 12 of the colleges applied for university status in 2019.[170] By mid-2024, 11 of those member institutions (two subsequently merged) had been awarded university title with the 12th expected to gain that status during 2024–25, and another university had joined.[171]

The university's December 2018 statutes, made under the 2018 act, allowed for member institutions to have either "the status of a college" (1.3.8(a)) or "the status of a university" (1.3.8(b)).[172] In its April 2024 statutes this was revised to having "legal status either as a university or another form of educational, academic or research institution", with no mention of colleges specifically and without subdividing the member institutions into two classes,[173] although the university's ordinances from July 2024 do still divide member institutions into those having "legal status as an educational, academic or research institution but not as a university" (5.A.1.1(a)) and those with "the status of a university" (5.A.1.1(b)).[174]

As originally established in 1836, London was an examining board and degree awarding body for affiliated colleges. Starting with University College London (UCL) and King's College London, which were named in the original charter, the list of affiliated colleges grew to include everything from grammar schools to the universities of the British Empire by 1858, when the affiliated college system was abandoned and London's degree examinations were thrown open to anyone. Following a campaign led by UCL and King's in the late 19th century, the university became a federal body in 1900.

Later the expansion of the university saw the growth of the small specialist colleges such as the Royal Academy of Music and Institute of Education, University of London (now part of UCL) either by being established within or merging into the university.

The constitution evolved during the 20th century, with power shifting towards the central University and then back towards the colleges. In the mid-1990s the colleges gained direct access to government funding and the right to confer University of London degrees themselves, and from 2008 those colleges that held their own degree awarding powers were allowed to use them while remaining part of the federation.

The University of London also has three central academic bodies: the School of Advanced Study, the University of London Institute in Paris (ULIP), and the University of London Worldwide, which are under the direct control of the central university and are not considered member institutions.[175] The School of Advanced Study and ULIP are both listed bodies as institutions of a university (as was the University Marine Biological Station Millport).[176]

University of the Arts London

The University of the Arts London (UAL) comprises six specialist art and design colleges, dating from the 1850s to the 1960s, that were brought together for administrative purposes.[177] The colleges are not listed bodies and do not have separate legal identities,[178] but maintain their separate identity and teach their own courses within the university.[179]

University of the Highlands and Islands

The University of the Highlands and Islands (UHI) is a federal collegiate university consisting of 13 independent "academic partner" colleges and a central executive office.[180] Like the colleges of Oxford, Cambridge and Durham, and those of London prior to the mid-1990s, UHI colleges are Listed Bodies.

Universities with associated colleges

A few universities, while operating as unitary institutions, have associated colleges in federal relationships.

Queen's University Belfast

Queen's University Belfast has a federal relationship with two associated university colleges, Stranmillis University College[181] and St Mary's University College.[182] These are listed bodies under part two of the listed bodies order, the same status as colleges of Oxford, Cambridge, Durham and the University of the Highlands and Islands.[183]

University of South Wales

The University of South Wales owns as subsidiary companies the Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama[184] and Merthyr Tydfil College (a further and higher education college).[185] [186] Like the university colleges associated with Queen's University Belfast, these are listed bodies under part two of the listed bodies order.[187]

University of Wales Trinity St Davids

The University of Wales Trinity St David (UWTSD) owns Coleg Sir Gâr, a further and higher education college, which has Coleg Ceredigion, another further and higher education college, as a subsidiary.[188][189] Like the university colleges associated with Queen's University Belfast, these are listed bodies under part two of the listed bodies order.[190]

Former federal universities

University of Durham

The University of Durham has had, in addition to the extant collegiate system described in § Durham University above, both forms of federal system at various points during its existence. In the 19th century it had two associated colleges in Newcastle upon Tyne: the Durham University College of Medicine (and it its predecessor institutions) from 1852; and Armstrong College (and its predecessor institutions) from 1871. This arrangement lasted until 1909, when Durham was converted into a fully federal university. This consisted of a Durham division, incorporated as the Durham Colleges, and a Newcastle division, consisting of the College of Medicine and Armstrong College until they merged in 1937 to form King's College. The federation was dissolved in 1963 when King's College became the independent University of Newcastle upon Tyne.

Victoria University of Manchester

The Victoria University of Manchester affiliated the University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology (UMIST) from 1905 to 1994) and the Manchester Business School (set up jointly with UMIST in 1965) until the merger of UMIST and the Victoria University of Manchester in 2004, forming the current University of Manchester.[191] These were both listed bodies as institutions of a university under the listed bodies order.[192]

Queen's University of Ireland

The Queen's University of Ireland was a federal university from 1850 to 1880, taking in Queen's College Belfast, Queen's College Cork and Queen's College Galway. The university was replaced by the Royal University of Ireland, an examining and degree-awarding body without member institutions, in 1880. This was in turn replaced by Queen's University Belfast and the National University of Ireland in 1908.

University of Surrey

The Federal University of Surrey was a federal university from 2000 to 2004, consisting of the University of Surrey and the University of Surrey Roehampton. The federation was dissolved in 2004 when Roehampton became the independent Roehampton University.

Victoria University

The Victoria University was a federal university that existed from 1880 to 1904, with colleges in Manchester (1880–1904), Liverpool (1884–1903) and Leeds (1887–1904). The federation was dissolved when its Corea became independent universities, with the university merging with its original college in Manchester to form the Victoria University of Manchester.

University of Wales

In the University of Wales, colleges were the lower tier of institutional membership in the federal structure, below constituent institutions, following the reorganisation of the university in 1996. Prior to this, the member institutions were all called colleges. After 2007 the colleges and constituent institutions all became independent universities, with the University of Wales shifting to a confederal structure where it validated degrees from these and other institutions. This arrangement ended in 2011 and it was announced that the university would merge with the University of Wales Trinity Saint David. From August 2017 the two institutions have been functionality merged.[193]

See also

- University college § United Kingdom

- List of residential colleges § United Kingdom

- House system

- Residential college

- Common room (university) § Collegiate universities

- Head of college

References

- ^ "The Education (Listed Bodies) (England) Order 2013 – Explanatory Note". Retrieved 20 February 2016.

- ^ "College structure". Cardiff University. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

- ^ a b Jacques Verger (16 October 2003). "Patterns". In Hilde de Ridder-Symoens; Walter Rüegg (eds.). A History of the University in Europe. Vol. 1, Universities in the Middle Ages. Cambridge University Press. pp. 52–53, 61–62. ISBN 9780521541138.

There were schools in operation in Oxford from at least as early as the middle of the twelfth century; an embryonic university organization was in existence from 1200, even before the first papal statutes (1214), which were complemented by royal charters, had established its first institutions

- ^ a b Tim Geelhaar (8 August 2011). "Did the West Receive a "Complete Model"?". In Jörg Feuchter; Friedhelm Hoffmann; Bee Yun (eds.). Cultural Transfers in Dispute: Representations in Asia, Europe and the Arab World since the Middle Ages. Campus Verlag. p. 76. ISBN 9783593394046.

- ^ L. W. B. Brockliss (2016). The University of Oxford: A History. Oxford University Press. pp. 63–64. ISBN 978-0-19-924356-3.

- ^ "About the College". Peterhouse, University of Cambridge. Retrieved 7 August 2025.

- ^ "History". New College, Oxford. Statutes. Retrieved 6 August 2025.

His statutes demanded a college comprised of a warden and seventy fellows, graduates and, a novelty at the time, undergraduates. Senior Fellows taught the juniors which marked the beginning of a formal tutorial system.

- ^ Report of Her Majesty's Commissioners appointed to Inquire Into the State, Discipline, Studies and Revenues of the University and Colleges of Cambridge: Together with the Evidence, and an Appendix. HMSO. 1852. p. 2.

- ^ Report of Her Majesty's Commissioners Appointed to Inquire Into the State, Discipline, Studies, and Revenues of the University and Colleges of Oxford Together with the Evidence, and an Appendix. HMSO. 1852. p. 8.

- ^ "Preface: Constitution and Statute-making Powers of the University". University of Oxford Statutes. 4. The Laudian Code. Retrieved 6 August 2025.

- ^ "Proposed Admission of Women to Membership of the University and the Degrees in the University". Oxford University Gazette. 22 October 1919. IV. Matriculation, p. 108. Supplement to no. 1593

- ^ "Universities". Hansard. 4 May 1837. Retrieved 6 August 2025.

- ^ William Hamilton (June 1831). "Universities of England – Oxford". The Edinburgh Review. Vol. 107. pp. 443–444.

- ^ Matthew Andrews (June 2018). Universities in the Age of Reform, 1800–1870. Springer International Publishing. pp. 65–66. ISBN 978-3-319-76726-0.

- ^ Rosemary Ashton (2012). "A 'Quasi-Collegiate Experiment in Gordon Square". Victorian Bloomsbury. Yale University Press. p. 183. ISBN 978-0-300-15448-1.

- ^ Matthew Andrews (June 2018). "Collegiate Model". Universities in the Age of Reform, 1800–1870. Springer International Publishing. pp. 65–71. ISBN 978-3-319-76726-0.

- ^ Matthew Andrews (June 2018). "The Durham Professorial Model". Universities in the Age of Reform, 1800–1870. Springer International Publishing. pp. 111–115. ISBN 978-3-319-76726-0.

- ^ R. J. O'Hara (20 December 2004). "The Collegiate System at the University of Durham". The Collegiate Way. Archived from the original on 16 April 2025. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- ^ "Pasta with a side order of philosophy, please". Times Higher Education. 20 August 2004.

Although the historical roots of collegiate organisation are to be found in Oxford and Cambridge universities, the corporate independence of Oxbridge colleges is not likely to be reproduced elsewhere. But there is a growing trend in US higher education to create decentralised residential colleges more along the lines of the colleges at Durham University than at Oxford or Cambridge, and this trend holds great promise for the improvement of student life.

- ^ W. E. Sherwood (1900). Oxford Rowing. Henry Frowde. p. 8.

- ^ "Beyond the Boat Race – Rowing at Cambridge University". World Rowing. 18 May 2015. Retrieved 27 July 2025.

- ^ "Senate Cup". Durham College Rowing. Retrieved 27 July 2025.

- ^ "Keble sport, the early years". Keble College. Retrieved 22 July 2025.

- ^ "Nineteenth and twentieth centuries". University of Cambridge. 28 January 2013. Retrieved 22 July 2025.

- ^ "Durham University Journal volume 12, parts 1-18". Durham University Journal. Vol. 12. Durham University. 1898.

- ^ "A Remedy for Rents: Darning samplers and other needlework from the Whitelands College Collection". Goldsmiths, University of London library. Retrieved 9 August 2025.

- ^ "Special Collections & Archives: Whitelands College Archive". University of Roehampton library. Retrieved 9 August 2025.

- ^ Matthew Andrews (June 2018). Universities in the Age of Reform, 1800–1870. Springer International Publishing. p. 237. ISBN 978-3-319-76726-0.

- ^ "Brief History of Hatfield" (PDF). Hatfield College, Durham. p. 5. Retrieved 8 August 2025.

- ^ "Building renamed in founder's honour". The Northern Echo. 7 May 2005.

- ^ Matthew Andrews (June 2018). Universities in the Age of Reform, 1800–1870. Springer International Publishing. pp. 69–70. ISBN 978-3-319-76726-0.

- ^ Phyllis Weliver (2017). Mary Gladstone and the Victorian Salon: Music, Literature, Liberalism. Cambridge University Press. p. 20.

- ^ Josceline Dimbleby (2007). May and Amy. Crown Publishing Group. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-307-42126-5.

- ^ Stephen Burt; Tim Burt (2022). "Durham City: a brief history". Durham Weather and Climate. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-264337-7.

- ^ Report of Her Majesty's Commissioners Appointed to Inquire Into the State, Discipline, Studies, and Revenues of the University and Colleges of Oxford. HMSO. 1852. p. 41.

- ^ L. W. B. Brockliss (15 April 2016). The University of Oxford: A History. Oxford University Press. pp. 353, 369, 370. ISBN 978-0-19-101730-8.

- ^ a b "Preface: Constitution and Statute-making Powers of the University". University of Oxford. 5. University Commissioners 1850–51. Retrieved 8 August 2025.

- ^ W. W. Grave (1983). Fitzwilliam College Cambridge, 1869-1969. Fitzwilliam Society. p. 12.

- ^ H. J. R. (7 October 1909). "College reform under the Cambridge University Act of 1856". The Eagle. Vol. 31. St. John's College, Cambridge. pp. 195–196.

- ^ a b John William Adamson (1919). "University Legislation". A Short History of Education. Cambridge University Press. p. 282.

- ^ "Nineteenth and twentieth centuries". University of Cambridge. 28 January 2013. Retrieved 8 August 2025.

- ^ a b c d "College History". St Catherine's College, Oxford. Retrieved 10 August 2025.

- ^ a b c d Hugh Jones (16 February 2024). "Higher education postcard: St Catherine's College, Oxford". Wonkhe. Retrieved 10 August 2025.

- ^ a b L. W. B. Brockliss (2016). "A Century of Reform". The University of Oxford:A History. Oxford University Press. pp. 369–370. ISBN 978-0-19-924356-3.

- ^ a b c d Hugh Jones (19 August 2022). "Higher education postcard: Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge". Wonkhe. Retrieved 10 August 2025.

- ^ a b "Our History". Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge. Retrieved 10 August 2025.

- ^ Matthew Andrews (June 2018). "Unattached Students". Universities in the Age of Reform, 1800–1870. Springer International Publishing. pp. 273–274. ISBN 978-3-319-76726-0.

- ^ a b c "History". St Cuthbert's Society.

- ^ "Women and Education". University College London library. 25 May 2021. Higher Education. Retrieved 10 August 2025.

- ^ "The Campaign for Women's Education". Newnham College. 13 February 2024. Retrieved 10 August 2025.

- ^ a b "Women Making History: the centenary". University of Oxford. Retrieved 10 August 2025.

- ^ "About". St Anne's College, Oxford. Retrieved 10 August 2025.

- ^ "Durham University Records: Colleges: College of St Hild and St Bede". Durham University library. St Hild's College. Retrieved 10 August 2025.

- ^ a b "Durham University Records: Colleges: St Aidan's College". Durham University Library. College history. Retrieved 10 August 2025.

- ^ "Durham University Records: Colleges: St Mary's College". Durham University Library. Retrieved 10 August 2025.

- ^ "Timeline". Education and Activism. University of Oxford. Retrieved 10 August 2025.

- ^ "Charter and Supplemental Charter 2025" (PDF). Newnham College. Retrieved 10 August 2025.

- ^ Hugh Jones (1 March 2024). "Higher education postcard: Girton College, Cambridge". Wonkhe.

- ^ Ted Tapper; David Palfreyman (2019). "The collegial tradition in English higher education". In Antony Drew; Gordon Redding; Stephen Crump (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Higher Education Systems and University Management. Oxford University Press. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-19-255568-7.

- ^ H E Salter; Mary D Lobel, eds. (1954). "Campion Hall". A History of the County of Oxford. Vol. 3, the University of Oxford. London: Victoria County History – via British History Online.

- ^ "Selwyn History". Selwyn College. Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- ^ "History". St Anne's College. Retrieved 12 August 2025.

- ^ "History". St Anne's College. Retrieved 12 August 2025.

- ^ "St Cuthbert's Society". University of Durham Calendar 1975–76. p. 226.

- ^ "About the College". Nuffield College. Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- ^ "History". St Antony's College. Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- ^ "Foundation of the College". St Cross College. Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- ^ "History of Linacre College". Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- ^ "Our origins". Wolfson College. Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- ^ "History of Green Templeton". Green Templeton College. Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- ^ "Darwin College - 60th Anniversary". Darwin College. Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- ^ "College Timeline". Wolfson College. Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- ^ "Support the College". Darwin College. Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- ^ "History of Clare Hall". Clare Hall. Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- ^ "Graduate Society". Report by the Vice-chancellor and Warden for the year 1965-66. Durham University. 1966. p. 115.

- ^ Nigel Watson (2004). From the Ashes: The Story of Grey College, Durham. James & James. pp. 13, 17.

- ^ Malcolm Dean (2 June 2008). "Revolutionary road". The Guardian.

- ^ James Jackson Walsh. "Postgraduate Technological Education in Britain: Events Leading to the Establishment of Churchill College, Cambridge, 1950-1958". Minerva. 36 (2 (Summer 1998)): 147–177. JSTOR 41821101.

- ^ Nigel Watson (2004). From the Ashes: The Story of Grey College, Durham. James & James. pp. 5, 17, 28.

- ^ a b Ted Tapper; David Palfreyman (2010). The Collegial Tradition in the Age of Mass Higher Education. Springer. pp. 69, 72–73. ISBN 978-90-481-9154-3.

- ^ Michael Beloff (1968). The plateglass universities. Secker & Warburg. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-436-04001-6.

- ^ "History of the College". Langwith College, York. Archived from the original on 22 January 2015.

- ^ "History of the College". Derwent College, York. Archived from the original on 22 January 2015.

- ^ "1959–1969". University of Kent. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007.

- ^ Michael Beloff (1968). The plateglass universities. Secker & Warburg. pp. 96, 135. ISBN 978-0-436-04001-6.

- ^ "St Cuthbert's Society". University of Durham Calendar 1975–76. p. 226. Retrieved 15 August 2025.

- ^ David Malcolm (7 March 2018). ""As much freedom as is good for them" – looking back at in loco parentis". Wonkhe.

- ^ "Obituary – Professor Sir Bernard Williams". The Guardian. 13 June 2003. Retrieved 8 May 2009.

- ^ Van Mildert College 60th Anniversary Brochure. Durham University. 4 February 2025. p. 7 – via Issuu.

- ^ "50 Years of Collingwood" (PDF). Durham University. Retrieved 30 January 2025.

- ^ "5 Oxford Men's Colleges To Admit Women in 1974". The New York Times. 29 April 1972.

- ^ "About Robinson". Robinson College. Retrieved 17 August 2025.

- ^ "Cambridge University: Youngest college granted Grade II* listed status". BBC News. 18 November 2022.

- ^ "The initiatives and events that shaped our development". Girton College. 1977 Going mixed. Retrieved 15 August 2025.

- ^ "History". University of Oxford. 1920. Retrieved 30 January 2025.

- ^ Nick Morrison (25 January 2018). "Women Outnumber Men At Oxford For First Time In 800 Years". Forbes.

- ^ Claire Gao (6 September 2023). "Women at Magdalene: A chequered history". Varsity.

- ^ "Celebrating 30 Years of Hatfield Women". Archived from the original on 23 October 2019. Retrieved 30 January 2025.

- ^ "Celebrating Chad's Women at the Ladies' and Friends' Formal". St Chad's College. 27 February 2019. Retrieved 30 January 2025.

- ^ "Chadswomen". The Chadsian. 2018. p. 27.

- ^ Robin Simmons (8 February 2017). "What happened to teacher-training colleges?". Schools Week.

- ^ "History". College of St Hild and St Bede. Retrieved 16 August 2025.

- ^ "Durham University Records: Colleges". Durham University library. Neville's Cross College. Retrieved 16 August 2025.

- ^ a b "Froebel History". Froebel College, Roehampton. From Roehampton Institute for Higher Education to University of Roehampton. Retrieved 16 August 2025.

- ^ Celebrating 125 Years (PDF). St Mary's College, Durham. 2024. p. 7. Retrieved 30 January 2025.

- ^ a b Josie Gurney Read (5 December 2013). "Oxford hall announces decision to admit women". The Telegraph.

- ^ "Last all-male Oxford institution votes to admit women". BBC News. 4 June 2015.

- ^ "Durham University Records: Colleges: Ustinov College". Durham University library. Retrieved 16 August 2025.

- ^ Ryan Gould (26 July 2016). "Queen's Campus relocation to force Ustinov move". Palatinate.

- ^ "Colleges, rooms and prices". University of York. Retrieved 16 August 2025.

- ^ "College Catering". Durham University. Retrieved 16 August 2025.

- ^ "St Cross College, Oxford". About the College. Retrieved 16 August 2025.

St Cross provides high quality facilities for study, with self-catering accommodation at sites across Oxford.

- ^ Ted Tapper; David Palfreyman (2010). The Collegial Tradition in the Age of Mass Higher Education. Springer. p. 71.

- ^ a b "College Masters" (PDF). University of Kent. Retrieved 31 July 2025.

- ^ a b "Ordinances" (PDF). University of Kent. June 2025. Retrieved 24 July 2025.

- ^ a b "Ordinances" (PDF). University of Kent. July 2024. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 February 2025.

- ^ a b "Governance Review outcome and next steps" (pdf). 16 March 2023. Retrieved 17 August 2025.

- ^ a b "A-Z of colleges". University of Oxford. Retrieved 7 August 2025.

- ^ "Statute V: Colleges, Societies, and Permanent Private Halls". University of Oxford. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ "About". Reuben College, Oxford. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ "Reuben College Buildings 2022". 27 October 2021. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ^ a b "Oxford & Cambridge Mature Students: A Complete Guide". Uni Admissions. 25 August 2021. Should I go to a mature college?. Retrieved 7 August 2025.

- ^ "College listing". University of Oxford. Retrieved 7 August 2025.

- ^ "All Souls College". Retrieved 7 August 2025.

- ^ a b Oxbridge Admissions (Report). Sutton Trust. 4 February 2016. p. 2.

- ^ "Statutes and Ordinances". University of Cambridge. Statute G: Colleges and Collegiate Foundations; Ordinances Chapter XV: Institutions Recognized under Statute G I. Retrieved 7 August 2025.

- ^ "Supervisions and modes of assessment at Cambridge". University of Cambridge. Retrieved 7 August 2025.

- ^ "Statutes". Durham University. 12. Colleges and Societies. Retrieved 3 August 2025.

- ^ "Ordinance 7 Colleges and Societies". Durham University. Retrieved 3 August 2025.

- ^ "Minutes of a meeting held on 7 December 2021 in the Ustinov Room, Van Mildert College" (PDF). Durham university. 45. Financial Agreement and Memorandum of Understanding with the Recognised Colleges 2021/22 - 2025/26. Retrieved 5 August 2025.

- ^ "Cranmer Hall – an introduction". Cranmer Hall. Retrieved 5 August 2025.

- ^ "History". St Chad's College, Durham. Retrieved 5 August 2025.

- ^ "What is college membership?". Durham University. Retrieved 5 August 2025.

- ^ "Postgraduate College Comparison Table". Durham University. Retrieved 5 August 2025.

- ^ "Our services: Libraries and site information: College Libraries". Durham University Library. Retrieved 5 August 2025.

- ^ "Statutes". Durham University. 21. Student Organisations. Retrieved 5 August 2025.

- ^ "Participation". Team Durham. Retrieved 5 August 2025.

- ^ "Statutes". Durham University. 4. The Debate. Retrieved 5 August 2025.

- ^ "Ordinance 3 Council". Durham University. Appendix 4 Reserved Matters. Retrieved 5 August 2025.

- ^ James Tillotson; Will Dixon (26 July 2024). "Explained: How does Durham University allocate college accommodation?". Palatinate.

- ^ "Preliminary College Membership Allocation Process – Undergraduate Students (2025 Entry)". Durham University. Retrieved 5 August 2025.

- ^ "Undergraduate Colleges Guide" (PDF). Durham University. pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b Becks Fleet; Ben Webb (28 February 2023). "Rushford Court to become Durham University's 18th college". Palatinate.

- ^ a b Rachel Conner (28 September 2017). "Durham University's Ustinov College officially moves to Sheraton Park and welcomes first students". The Northern Echo.

- ^ Martha McHardy (16 September 2020). "South College welcomes its first new students". Palatinate.

- ^ Rachel Conner-Hill (7 September 2018). "Work starts on Durham University's new £80m colleges". Northern Echo.

- ^ Elliot Burrin; Luke Alsford; Seana Barrett; Will Dixon (13 June 2024). "Durham's "worst kept secret": what are the plans for Durham's 19th college?". Palatinate.

- ^ "Charter, Statutes and Ordinances" (PDF). University of Lancaster. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- ^ "Our Colleges". University of Lancaster. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- ^ "Staff Members". Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ^ "Our Colleges". Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ^ "Undergraduate Accommodation". Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ^ "College Membership Fees". Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ^ "Carter Shield League". Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- ^ "Colleges, University of York".

- ^ a b "Ordinance 13: Academic Organisation". University of York. Colleges (13.13–13.15). Retrieved 17 August 2025.

- ^ Haydn Lewis (11 March 2023). "University of York to officially open David Kato College". The Press. Retrieved 17 August 2025.

- ^ {{cite web|url=https://www.york.ac.uk/colleges/wentworth/%7Ctitle=Welcome to Wentworth Graduate College!|website=Wentworth Graduate College|access-date=17 August 2025

- ^ "Societies".

- ^ "College Sport". College Sport at York. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- ^ "New College Varsity". York Vision. 29 October 2013. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ Matt Roberts (1 March 2016). "Durham lose College Varsity to York". Palatinate. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ Josh Males (10 March 2017). "Varsity triumph highlights strength in depth". Palatinate. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "Articles of Association". University of Roehampton. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- ^ "Annual report and financial statements 2012 – 2013" (PDF). University of Roehampton. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- ^ "Your elected officers". Roehampton Students' Union. Retrieved 17 August 2025.

- ^ "Colleges". University of Kent. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ^ "Colleges trail: exploring the past and present" (PDF). University of Kent. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ "Your guide to university accommodation: What are your options at Canterbury?". University of Kent. 9 April 2025. Retrieved 24 July 2025.

- ^ "UCL statement on University of London Act 2018". University College London. 11 March 2019. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ "Financial Statements 2024–2025" (PDF). University of London. pp. 20–21, 24. Retrieved 7 August 2025.

- ^ "Statutes" (PDF). University of London. 20 December 2018. 1.3.8 "Member Institution". Retrieved 17 August 2025.

- ^ Statutes April 2024 V1.pdf "Statutes" (PDF). University of London. 19 April 2024. 1.3.2 "Member Institution". Retrieved 17 August 2025.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ 5 – Federation Membership and Funding Federal Activities %281%29.pdf "Federation Membership and Funding Federal Activities: Ordinance 5" (PDF). University of London. 11 July 2024. A. Member institutions/ federation members of the University of London. Retrieved 17 August 2025.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ "How the University is run". University of London. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ "The Education (Listed Bodies) (England) Order 2013". Legislation.gov.uk. 27 November 2013. University of London. Retrieved 19 August 2025.

- ^ "University of the Arts London (formerly The London Institute): A Brief History" (PDF). University of the Arts London. 2019. Retrieved 19 August 2025.

- ^ "Charitable Status". University of the Arts London. Retrieved 19 August 2025.

- ^ "Colleges". University of the Arts London. Retrieved 19 August 2025.

- ^ "UHI Equality Outcome and Mainstreaming Report 2019" (PDF). Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ "Queen's and Stranmillis renew century-long partnership to enhance education in Northern Ireland". Queen's University Belfast. 4 March 2025. Retrieved 19 August 2025.

- ^ "Queen's University Belfast and St Mary's University College renew historic partnership". Queen's University Belfast. 16 January 2025. Retrieved 19 August 2025.

- ^ "The Education (Listed Bodies) Order (Northern Ireland) 2018: Schedule Part 2 – Institutions of a University". Legislation.gov.uk. 11 January 2018. Queen's University Belfast. Retrieved 19 August 2025.

- ^ "Corporate Information". Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama. Retrieved 19 August 2025.

- ^ "Higher Education". Merthyr Tydfil College. Retrieved 19 August 2025.

- ^ "Annual Report and Financial Statements for the year ended 31st July 2024" (PDF). Merthyr Tydfil College. p. 3. Retrieved 19 August 2025.

- ^ "University of South Wales / Prifysgol de Cymru". 15 March 2016. Retrieved 19 August 2025.

- ^ "Higher Education". Coleg Sir Gâr Coleg Ceredigion. Retrieved 19 August 2025.

- ^ "Governance". Coleg Sir Gâr Coleg Ceredigion. Retrieved 19 August 2025.

- ^ "University of Wales Trinity St David". 15 March 2016. Retrieved 19 August 2025.

- ^ "University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology Institutional Audit". QAA. November 2003. Archived from the original on 15 August 2007.

- ^ "The Education (Listed Bodies) Order 1988". 21 November 1988. University of Manchester. Retrieved 19 August 2025.

- ^ "University of Wales Merger – Frequently Asked Questions" (PDF). University of Wales. January 2018. Retrieved 14 September 2020.