Climate finance in Guatemala

Climate finance in Guatemala brings together resources mobilized by public and private institutions and international partners to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and strengthen the country's resilience to the impacts of climate change . Despite accounting for only 0.08% of global CO₂ emissions in 2023 (approximately 43.98 Mt), Guatemala is among the nations most exposed to extreme events— prolonged droughts, tropical storms, and hurricanes that, in 2020, with Eta and Iota, highlighted its agricultural and social vulnerability. [1][2][3]

Domestically, the country has a set of legal instruments and financing programs that include the Renewable Energy Incentive Law (Decree 52-2003), the 2013 Climate Change Framework Law, and the PEG-5-2025 auction, which aims to contract 1,400 MW of clean energy by 2030.[4][5] In 2024, the government allocated approximately US$6.5 million to the National Climate Change Fund (FONCC), earmarking 80% for adaptation and 20% for mitigation, while ambitious targets set 80% renewable generation by 2030 and increased energy efficiency by 2050.[6][7]

The private sector has increasingly adopted green instruments, as demonstrated by CMI Energy's $700 million green bond issuance, Banco Promerica Guatemala's $500 million green bond, and CABEI's $30 million credit line to Banco Agromercantil.[8][9][10] At the international level, membership in SIEPAC and partnerships with the World Bank, the World Food Programme, and the Development Bank of Latin America and the Caribbean have leveraged investments in forest conservation, climate insurance, and resilient infrastructure projects.[11][12][13]

However, Guatemala's climate finance system faces criticism regarding its transparency and effectiveness in allocating resources. Hydroelectric projects have been the target of allegations of human rights violations and inadequate consultation with indigenous communities, while funding mechanisms are often subject to misuse or excessive bureaucracy, limiting direct access for the most affected populations.[14][15]

Climate context and vulnerabilities

Climatic context

Guatemala is among the world's most vulnerable countries to climate change. In 2010, it was ranked second on the Global Climate Risk Index due to its high exposure to and frequency of extreme events such as droughts and storms.[2] About half of the country's workforce depends on agriculture, and in 2018, approximately 300,000 subsistence farmers reported crop losses due to drought.[16]

Guatemala is located in a complex geographic area marked by the intersection of three tectonic plates and the Intertropical Convergence Zone, which accentuates the occurrence of earthquakes, volcanic activity, floods, and tropical storms.[17] Hurricanes Eta and Iota, which hit the country in November 2020, exemplified the severe impact of these phenomena, causing significant economic losses and confirming the country's macro-critical vulnerability.[3]

Economic and social context

Agriculture is a mainstay of Guatemala's economy , accounting for about 10% of GDP and employing over a quarter of the workforce, with key exports including bananas, coffee, palm oil, and raw sugar.[18][19] However, the sector is highly vulnerable to climate shocks, as evidenced in 2024 when El Niño -intensified droughts devastated staple crops such as corn and beans across tens of thousands of hectares, severely compromising food security.[20]

Chronic malnutrition is a persistent crisis in Guatemala, which has the highest rate in Latin America and one of the highest in the world—about half of children are stunted, a problem exacerbated by prolonged droughts and recurring periods of food shortages.[20]

About 25 percent of Guatemala's territory is agricultural land, while the remainder is mostly forested or used for other purposes.[21] However, forest cover has declined significantly—from 50 percent in 1950 to about 35 percent today—due to agricultural expansion, illegal deforestation, and a heavy reliance on firewood as an energy source in rural areas.[22]

Natural resources are of great economic importance in the country, as wood and sugarcane byproducts provide more than half of the country's energy, especially in rural households, where firewood remains the main fuel for cooking and heating, even when some families are able to switch to cleaner sources.[23]

.jpg)

Guatemala's transportation infrastructure is limited, with only 43% of its 17,440 km of roads paved, resulting in slow and costly transportation of goods—generating high logistics costs.[24]

Poor connectivity and poor road maintenance contribute to inefficiencies in the transportation sector, which in turn exacerbate air quality problems, especially in urban areas.[25] Air pollution in the country is primarily driven by an aging vehicle fleet, including outdated municipal buses and imported used cars that do not meet modern emissions standards, resulting in extremely high levels of pollutants such as carbon monoxide and fine particulate matter (PM2.5).[20] Studies have recorded concentrations of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) in Guatemala City far above the limits recommended by international health guidelines, reaching 800 mg/m³ in a one-hour period, an amount that can make an adult sick simply by being on the street.[25] The situation is exacerbated by insufficient air quality regulations and weak oversight, as well as stagnation in public transportation modernization projects, such as the Transurbano , which has been marred by corruption.[25]

In 2023, Guatemala's total CO₂ emissions were approximately 43.98 million metric tons, representing only 0.08% of global emissions.[1] The energy and transportation sectors—especially the burning of petroleum products —are the main sources, accounting for over 92% of combustion-related emissions in the country, while other relevant factors include deforestation , land-use change, and industrial activities. [26][22]

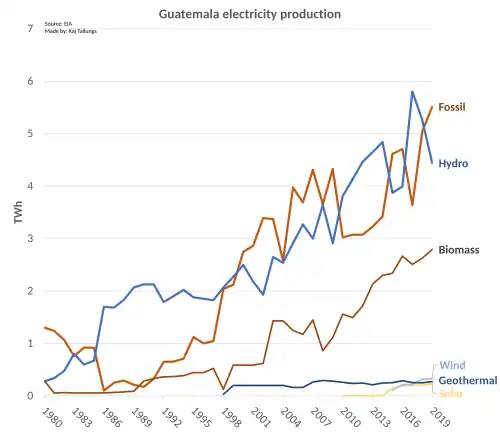

Energy context

Guatemala's energy supply relies heavily on biofuels and waste, accounting for 60% of the country's energy supply.[23] Firewood alone accounts for more than half of total energy consumption, especially in rural households where traditional cooking methods are still widely used despite the availability of modern fuels.[27][28] The sugar industry plays a significant role by generating electricity from sugarcane bagasse and producing ethanol from molasses, contributing to the country's renewable energy matrix. [29]

Despite Guatemala's strong potential for solar and wind energy, these sources currently represent only a small fraction of the national energy matrix.[23] Studies indicate that although solar and wind resources are abundant, their deployment has been limited by factors such as high upfront costs, infrastructure challenges, and the focus of public policy on other renewable sources such as hydropower and biomass.[28]

Guatemala's total installed electricity generation capacity is approximately 4.21 GW, with a per capita consumption of about 689 kWh per year.[30][31] Residential users dominate electricity consumption, accounting for 61.8% of total use, while the commercial and industrial sectors account for about 3.5% and 8.7%, respectively.[32]

The average residential electricity price in Guatemala is approximately US$0.295 per kWh, one of the highest in the region and well above the global average.[33][34] The largely privatized electricity generation sector, combined with limited grid access and high distribution costs in rural areas, drives up national average prices and disproportionately affects rural consumers.[35][36] The Comisión Nacional de Energía Eléctrica (CNEE) regulates the sector, while the INDE and private companies are responsible for supply.

Legal and institutional frameworks

Guatemala has set ambitious targets to achieve 80% of its electricity generation from renewable sources by 2030 and to expand energy efficiency across all sectors by 2050.[7][27] These goals build on a foundation in which renewables—primarily hydropower and biomass —already account for more than 60% of installed capacity.[23] The country has also committed to phasing out the inefficient use of biomass and promoting electric mobility —measures that will also reduce dependence on oil and firewood.[27]

Guatemala’s ambitious renewable energy expansion goals require substantial investments—at least $5 billion—to modernize grid infrastructure, expand energy storage capacity, and achieve rural electrification.[37][38] The recent launch of PEG-5-2025 , the largest energy auction ever held in the country, seeks to contract up to 1,400 MW of firm capacity from renewable and low-emission sources such as solar, wind, hydropower, geothermal, and natural gas, with 15-year contracts starting in 2030.[37]

The 2013 Climate Change Framework Law established a legal basis for climate action, requiring private companies to consider climate impacts and adopt appropriate technologies, and allowing participation in voluntary and regulated carbon markets—key steps toward integrating Guatemala into global emissions reduction efforts.[5]

Guatemala's National Strategy to Attract Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) seeks to foster a favorable environment for sectors such as renewable energy, with the aim of boosting green investment and strengthening the country's international competitiveness.[39] [24]

The Renewable Energy Incentive Law (Decree 52-2003) grants a 10-year exemption from VAT , income tax , and import tariffs for renewable energy projects, aiming to stimulate investment in solar, wind, hydropower, and biomass energy.[40] The PEG-5 Tender (2024–2025) further facilitates the integration of small-scale projects into the national grid by allowing their participation in energy auctions or sale in the spot market.[4]

Guatemala’s Foreign Investment Law provides a highly open environment for foreign investors, allowing 100% foreign ownership in any legal sector—including renewable energy—while guaranteeing free currency convertibility and profit repatriation.[41] This legal framework, combined with the Government’s National Strategy to Attract Foreign Direct Investment, positions Guatemala as a competitive destination for global capital.[42]

The proposed National Carbon Credit Program, with an expected allocation of $51 million, aims to further incentivize emissions reductions and strengthen Guatemala's role in carbon markets through the creation of a national credit certification system.[22]

Public funding

In 2024, the Guatemalan government allocated approximately US$6.5 million from the national budget to the National Climate Change Fund (FONCC), of which 80% was applied to adaptation projects and 20% to mitigation actions, with the aim of improving the transparency and effectiveness of public climate spending.[6]

Community forest management programs and incentives such as PINFOR and PINPEP have been implemented to engage local populations in reforestation and forest protection actions, although their effectiveness is often limited by unfavorable market conditions, poor agricultural services, and persistent poverty.[43][44]

Despite these mechanisms, central government capital spending has fluctuated between just 0.3% and 1% of GDP over the past decade, restricting fiscal space for new investments, including climate-related ones.[45] To increase domestic revenues, the K'atun 2032 National Development Plan and the Guatemala No Se Detiene program prioritize improvements in tax administration, budget transparency, and fiscal reform, aiming to strengthen the resource base available for public policies, including environmental ones.[46]

Private financing

The successful issuance of $700 million in green bonds by CMI Energy (Corporación Multi Inversiones), with an interest rate of 6.25% and maturity in 2029, exemplifies the growing use of green finance to support renewable energy projects in Guatemala and the region as a whole. [8][47]

Guatemalan banks are increasingly adopting financing instruments aligned with sustainability goals, reflecting a broader global trend in the banking sector. Sustainable bonds, green credit lines, and sustainability-linked loans are being used to direct resources toward renewable energy initiatives, support for micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises ( MSMEs ), and biodiversity conservation—as demonstrated by Banco Promerica Guatemala's $500 million sustainable bond and the Central American Bank for Economic Integration's (CABEI) $30 million credit line to Banco Agromercantil for green projects.[9][10]

MPC Energy Solutions has secured $34 million to build and operate a solar plant in Guatemala, highlighting the role of targeted financing in expanding the country's renewable energy capacity.[48]

International cooperation and external financing

Guatemala is integrated into the SIEPAC system (Sistema de Interconexión Eletrica de los País de América Central), a regional transmission network that connects six Central American countries (Belize, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Panama) to facilitate cross-border electricity trade and grid balancing. Guatemala's active participation in SIEPAC significantly increases its attractiveness to investors by providing access to a regional electricity market, which facilitates the export of surplus renewable energy to neighboring countries.[49]

In forest conservation efforts, a $52.5 million agreement was signed with the World Bank , aimed at reducing emissions from deforestation and promoting sustainable forest management.[50]

Launched in November 2022, the Disaster Risk Insurance and Finance in Central America Consortium brings together the World Food Programme, World Bank, and regional partners to develop climate insurance and financial instruments for up to 2 million smallholder farmers in Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras.[12][51]

The Development Bank for Latin America and the Caribbean doubled its funding for marine ecosystem protection and restoration initiatives in June 2025, increasing from US$1.25 billion (2022–2026) to US$2.5 billion (2025–2030) — demonstrating its financial capacity to also support climate-resilient infrastructure projects in member countries, including Guatemala.[13]

Main sectors benefited

Guatemala’s renewable energy sector has expanded in recent years, but this growth has not kept pace with the country’s rapid population growth, resulting in persistent energy poverty and limited access to modern energy services, especially in rural areas.[52] Although foreign direct investment in the electricity, water, and sanitation sectors nearly doubled from 2022 to 2023, reaching $48.4 million, the benefits of this investment are not equitably distributed, and many rural households still lack reliable and affordable access to electricity.[53][52]

Since 2020, Guatemala's agricultural sector has received significant international funding, notably from the Green Climate Fund (GCF) and the FAO: the Resilient Livelihoods of Vulnerable Small Farmers in the Mayan Landscapes and the Dry Corridor of Guatemala project mobilized US$29.8 million from the GCF and US$7 million from the Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA), providing technical assistance to 116,353 small farmers in agroforestry, soil conservation, and water management practices.[54] Furthermore, since August 2024, the UN World Food Programme ( WFP) has been financing training in sustainable practices focused on the "Dry Corridor," aiming to reduce the food vulnerability of rural communities.[55]

Impacts and results

Inaugurated in its phase IV at the end of 2023, the Renace hydroelectric plant (San Pedro Carchá) generates 301 MW and maintains an ecological flow 260% above that required by law, benefiting 21,000 inhabitants of 29 Q'eqchi' communities; it extracts about 10 tons of solid waste annually from the river, avoids 128,000 tCO₂e per year and, with the linked social programs, has reduced chronic child malnutrition by 32% and teenage pregnancy by 46% in the surrounding areas.[56][57]

Completed in less than three years and inaugurated in 2018, the Oxec II Project on the Cahabón River installed a 41 m high dam and three Kaplan units of 56 MW of total capacity, entering into operation without significant environmental incidents and serving as a benchmark for low head projects in Central America.[58]

Community forest concessions in the Maya Biosphere Reserve (Petén) cover approximately 2 million hectares under renewable 25-year contracts, enabling selective timber management and ecotourism activities.[59][60] In these areas, deforestation has remained at just 0.4% per year, in contrast to 36% in protected areas without community management, demonstrating the effectiveness of local management in forest conservation.[59][60] Independent estimates indicate that, in these ventures, sustainable management enabled the net capture of more than 2.7 million tons of CO₂ between 2013 and 2022, reinforcing the environmental effectiveness of these initiatives. [61]

On the southern coast, the Alas y Raíces Resilientes project restored more than 40 hectares of mangroves in the Chiquimulilla channel, resulting in the return of shrimp, herons, and migratory birds, as well as strengthening the role of women in restoration and environmental education activities. [62]

Criticism and controversies

Several hydroelectric projects financed as "green" have faced allegations of human rights abuses and failure to comply with the principle of free, prior, and informed consultation with Indigenous communities. In the case of the Santa Rita dam, built with backers including the World Bank, leaders such as Máximo Ba Tiul, spokesperson for the Peoples' Council of Tezulutlán , accuse the construction company of "serious violations of collective and individual human rights" by advancing construction without the consent of the Mayan Q'eqchi and Poqomchí communities, resulting in forced evictions, illegal arrests of leaders, and even homicides, including the murder of two children in 2013.[14] In projects such as the Palo Viejo and Xacbal dams, also registered with the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), Indigenous organizations have denounced a lack of transparent consultation mechanisms, replicating patterns of pressure and violence similar to those at Santa Rita, as highlighted by independent reports by Carbon Market Watch .[14][15]

The construction of the Chixoy Hydroelectric Plant, financed by the World Bank and IDB in the 1980s, resulted in the forced displacement of approximately 3,500 Achíe indigenous people and culminated in the Río Negro massacre (1982), an event that left up to 5,000 dead according to the Commission for Historical Clarification.[63][64] Local activists, such as Bernardo Caal Xol, emphasize that the compensation payments were insufficient and culturally inadequate, leading to the loss of sacred sites and traditional forms of subsistence.[15]

There is debate about the effectiveness of climate funding channels for local indigenous peoples. Levi Sucre Romero, an indigenous leader and board member of the Indigenous Peoples Support Group (GATC), warns that much of the funding—including funds from the Forest Tenure Funders Group—is diverted by government intermediaries or NGOs , leaving communities with only a fraction of the promised amounts. [65]

Future prospects

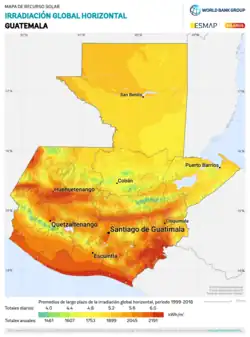

Guatemala has substantial untapped solar potential, with high solar irradiation levels ranging from 5.5 to 6.5 kWh/m² per day across much of the territory, especially in the southwestern and mountainous regions, making photovoltaic systems highly viable for both grid-connected and off-grid applications. [66]

In wind potential measurements, the Samororo station (Jalapa), in the east of the country, records an average annual speed of 6.7 m/s 30 m, while, in the south, Finca La Sabana reaches 6.8 m/s 30 m and Finca Candelaria (Sacatepéquez) records 6.0 m/s 20 m, highlighting the strong potential for wind projects in the southern and eastern regions of Guatemala. [67]

Guatemala has identified 69 sites with hydroelectric potential for up to 2,754 MW of total capacity, including 41 small projects totaling 292 MW and 28 medium and large projects with a total capacity of 2,462 MW, highlighting significant opportunities for hydropower expansion. [68] However, the country's heavy dependence on this source makes it vulnerable to droughts, which can reduce hydroelectric generating capacity by up to 35% during severe events. [69]

Guatemala's geothermal potential is estimated at around 1,000 MW, concentrated primarily along its volcanic belt , but only a small portion of this resource has been exploited to date.[70] Early explorations have identified certain promising geothermal areas, with Zunil and Amatitlán prioritized for development, and additional studies have been conducted in regions such as Tecuamburro ( Santa Rosa ) and Moyuta.[71]

See also

References

- ^ a b "EDGAR - The Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research". EDGAR. Archived from the original on 2025-06-27. Retrieved 2025-07-16.

- ^ a b Adil, Lina; Eckstein, David; Künzel, Vera; Schäfer, Laura (2025). Climate Risk Index (PDF) (Report). Germanwatch. p. 29.

- ^ a b Nugent, Ciara (2020-11-18). "Central American Leaders Demand Climate Aid as a Record Storm Season Batters the Region". TIME. Retrieved 2025-07-17.

- ^ a b "Open Tender PEG-5". CNEE (in Spanish). 2024. Retrieved 2025-07-16.

- ^ a b "DECREE NUMBER 7-2013" (PDF). Diario de Centro América (in Spanish). Republic of Guatemala. 2013-10-04. Retrieved 2025-07-17.

- ^ a b Gonzalez, Luis. "Government, private sector and civil society, in common front against climate change". República (in Spanish). Retrieved 2025-07-17.

- ^ a b "Indicative Plans of Generation and Transmission (Planes Indicativos de Generacion y Transmision)". International Energy Agency. 2017-02-24. Archived from the original on 2023-09-17. Retrieved 2025-07-16.

- ^ a b "CMI placed the largest green bond of a renewable energy company in the region: US$700 M". Revista Estrategia & Negocios (in Spanish). 2021-04-27. Retrieved 2025-07-17.

- ^ a b "Invest in securities in Guatemala: Bonds and promissory notes add up on the Stock Exchange". Prensa Libre (in Spanish). 2024-08-09. Retrieved 2025-07-17.

- ^ a b "BAM receives US$30 million". Prensa Libre (in Spanish). 2012-02-21. Retrieved 2025-07-17.

- ^ Barrera, Fabian. Central American Electrical Interconnection System (SIEPAC) (PDF) (Report). IRENA. Retrieved 2025-07-17.

- ^ a b Ralph, Hayley (2023-04-19). "How Caribbean and Central American producers manage disaster risk". Global Coffee Report. Retrieved 2025-07-17.

- ^ a b Abnett, Kate; Jessop, Simon (2025-06-07). "Latam-Caribbean development bank doubles oceans funding to $2.5 billion". Reuters. Retrieved 2025-07-17.

- ^ a b c Salazar, Maria Angeles (2015-10-08). "Green hydroelectric dam sparks serious allegations of human rights violations". Notícias ambientais (Mongabay) (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2025-07-17.

- ^ a b c Pyl, Bianca (2022-02-09). "Importance of prior consultation in the face of socio-environmental conflicts". Le Monde Diplomatique Brasil (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2025-07-17.

- ^ Walsh, Conor (2019-03-19). "Conor Walsh: Immigration and climate change in Central America". Arizona Daily Star. Retrieved 2025-07-17.

- ^ "Guatemala: 2021 Article IV consultation: press release; staff report; and statement by the Executive Director for Guatemala". International Monetary Fund. IMF country reports. Washington, D.C. 2021. p. 19. ISBN 9781513573205. Retrieved 2025-07-17.

- ^ "Guatemala GDP share of agriculture - data, chart". TheGlobalEconomy.com. Retrieved 2025-07-16.

- ^ "Guatemala (GTM) Exports, Imports, and Trade Partners". The Observatory of Economic Complexity. Retrieved 2025-07-16.

- ^ a b c "How climate change is driving hunger in Guatemala". Trócaire. 2025-03-18. Retrieved 2025-07-16.

- ^ "Guatemala Land Use: Land Area: Arable Land and Permanent Crops". CEIC. Retrieved 2025-07-16.

- ^ a b c "World Bank and Guatemala Sign US$52.5M Agreement To Cut Carbon Emissions And Preserve Forests". World Bank. Retrieved 2025-07-16.

- ^ a b c d "Guatemala". International Energy Agency. Retrieved 2025-07-15.

- ^ a b Hernandez-Roy, Christopher; Casique, Andrea; Hidalgo, Natalia (2025-04-01). "Assessing Guatemala as a Nearshoring Destination". Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). Retrieved 2025-07-17.

- ^ a b c "How Outdated Cars Live On in a Smoggy Afterlife". International Women’s Media Foundation. 2018-10-31. Retrieved 2025-07-17.

- ^ "Guatemala - Emissions". International Energy Agency. Retrieved 2025-07-16.

- ^ a b c "National Energy Efficiency Policy 2023–2050". Ministerio de Energía y Minas (in Spanish). 2023-06-23. Retrieved 2025-07-15.

- ^ a b Heltberg, Rasmus (2005-06-11). "Factors determining household fuel choice in Guatemala". Environment and Development Economics. 10 (3): 337–361. doi:10.1017/S1355770X04001858. Retrieved 2025-07-15.

- ^ Tay, Karla (2013). Guatemala Biofuels Annual Update on Ethanol and Biodiesel Issues (PDF) (Report). USDA Foreign Agricultural Service. Retrieved 2025-07-16.

- ^ "Guatemala - Electricity". International Energy Agency. Retrieved 2025-07-16.

- ^ "Guatemala Energy Situation". energypedia.info. Retrieved 2025-07-16.

- ^ "Guatemala - Efficiency & demand". International Energy Agency. Retrieved 2025-07-16.

- ^ "Guatemala electricity prices, December 2024". GlobalPetrolPrices.com. Retrieved 2025-07-16.

- ^ "Electricity prices around the world". GlobalPetrolPrices.com. Retrieved 2025-07-16.

- ^ Abbott, Jeff (2018-08-15). "Guatemala Communities Rebel Against High Energy Costs". NACLA. Archived from the original on 2025-01-24. Retrieved 2025-07-15.

- ^ "Expanding Access to Electricity: What Asia Can Learn from a Success Story in Latin America". The National Bureau of Asian Research (NBR). 2012-01-30. Retrieved 2025-07-16.

- ^ a b "Guatemala launches PEG-05-2025, its highest energy tender". pv magazine Latin America (in Spanish). 2025-04-24. Retrieved 2025-07-16.

- ^ "Guatemala launches US$5 billion energy tender to secure 1,400 MW by 2030". New Energy Events. 2025-04-25. Retrieved 2025-07-16.

- ^ Larios, Brenda (AGN) (2024-06-13). "Guatemala seeks to boost foreign direct investment by 2.7 billion dollars in four years". Agencia Guatemalteca de Noticias (in Spanish). Retrieved 2025-07-17.

- ^ Guatemala – El Motor de Centroamérica (PDF) (Report) (in Spanish). USAID / Ministerio de Economía. p. 23. Retrieved 2025-07-17.

- ^ "Guatemala". Energy Investment Risk Assessment (EIRA). p. 8. Retrieved 2025-07-17.

- ^ "Guatemala National Strategy to Attract Foreign Direct Investment 2024". Latam FDI. 2024-06-29. Retrieved 2025-07-17.

- ^ "PINPEP". Instituto Nacional de Bosques (in Spanish). Retrieved 2025-07-16.

- ^ Martínez, Herless. Forest Incentive Programs in Guatemala (UNDP) (Report) (in Spanish). PNUD. Retrieved 2025-07-17.

- ^ Guatemala: Selected Issues. IMF Staff Country Reports. International Monetary Fund. 2024. pp. 24–25. ISBN 9798400287459. Retrieved 2025-07-17.

- ^ "Latin American Economic Outlook 2024: Guatemala". OECD. 2024-12-09. Retrieved 2025-07-17.

- ^ Gándara, Natiana (2022-05-24). "Guatemala's stock market tunes green bonds and moves towards regionalization". Bloomberg Línea (in Spanish). Retrieved 2025-07-17.

- ^ "Delphos Advises MPC Energy Solutions on a USD 34 million Non-Recourse Project". PRLog. 2024-06-12. Retrieved 2025-07-17.

- ^ Economic Consulting Associates (ECA) (2010). Central American Electric Interconnection System (SIEPAC) (PDF) (Report). Transmission & Trading Case Study. London. Retrieved 2025-07-17.

- ^ Alonso, Laura; Menéndez, Alejandro Carrión; Montenegro, Fernando; Prat, Jordi; Quintero, Neile; Ruiz-Arranz, Marta; Teixeira, Gisele (2021). Guatemala IDB Group Country Strategy (PDF) (Report). IDB Group. p. 10. Retrieved 2025-07-17.

- ^ "Central America: Insurance and finance solutions for smallholder farmers". PreventionWeb. 2022-11-17. Retrieved 2025-07-17.

- ^ a b Henry, Candise L.; Baker, Justin S.; Shaw, Brooke K.; Kondash, Andrew J.; Leiva, Benjamin; Castellanos, Edwin; Wade, Christopher M.; Lord, Benjamin; Van Houtven, George (2021-12-27). "How will renewable energy development goals affect energy poverty in Guatemala?". Energy Economics: 105665. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2021.105665. Retrieved 2025-07-17.

- ^ "Direct foreign investment continues to flow to Guatemala, although it reaches small towns". Prensa Libre (in Spanish). 2023-07-21. Retrieved 2025-07-17.

- ^ Lacerda, Patricia (2021-07-16). "FAO prepares a US$66 million program for agriculture in Guatemala". The Rio Times. Retrieved 2025-07-17.

- ^ "As drought breeds hunger in Guatemala, farming program aims to help". Reuters. 2024-08-23. Retrieved 2025-07-17.

- ^ "Corporación Multi Inversiones: Renace Hydroelectric Complex National Development Foundation". Guatemala Business Daily. Retrieved 2025-07-17.

- ^ Hydro Review Content Directors (2018-12-11). "Hydropower included in winners of S&P Global Platts Global Energy Awards". Factor This™ / Renewable Energy World. Retrieved 2025-07-17.

- ^ Stocks, Carrieann (2020-04-01). "Oxec II hydroelectric project helping to energise Guatemala". NS Energy. Retrieved 2025-07-17.

- ^ a b "Mayan forest concessions in Guatemala: A model for combating deforestation". Le Monde (English edition). 2024-09-02. Retrieved 2025-07-17.

- ^ a b "Tropical forest success story under threat in Guatemala". BBC News. 2019-10-03. Retrieved 2025-07-17.

- ^ Stoian, D.; Rodas, A.; Butler, M.; Monterroso, I.; Hodgdon, B. (2018-12-15). "Forest concessions in Petén, Guatemala: A systematic analysis of the socioeconomic performance of community enterprises in the Maya Biosphere Reserve". CIFOR-ICRAF. Retrieved 2025-07-17.

- ^ Godínez, Andrea (2025-07-10). "The canal guardians who restore life in the Guatemalan Pacific". El País América (in Spanish). Retrieved 2025-07-17.

- ^ Johnston, Barbara Rose (2005). Tomo Uno: Study of the Legacy Elements of the Chixoy Dam (PDF) (Report) (in Spanish). Center for Political Ecology. Retrieved 2025-07-17.

- ^ Guatemala: Memory of Silence (PDF) (in Spanish). Comisión para el Esclarecimiento Histórico. 1999. ISBN 99922-54-06-8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-07-14. Retrieved 2025-07-17.

- ^ "Climate finance for indigenous communities". Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation. Retrieved 2025-07-17.

- ^ Aceituno Dardon, José Daniel; Farzaneh, Hooman (June 2024). "Techno-economic analysis of a hybrid photovoltaic-wind-biomass-battery system for off-grid power in rural Guatemala". Utilities Policy: 101762. doi:10.1016/j.jup.2024.101762. Retrieved 2025-07-16.

- ^ Velásquez, Gabriel Armando Velásquez; Chávez, Cristian Iván Samayoa; López, Marvin Yovani López; Perén, Jesús Fernando Alvarez; Isem, Giancarlo Alexander Guerrero; Milian, Fredy Alexander Lepe (2017). National Energy Plan 2017–2032 (PDF) (Report) (in Spanish). Ministerio de Energía y Minas. p. 52. Retrieved 2025-07-16.

- ^ Hydro Review Content Directors (2006-07-12). "Guatemala identifies 69 potential hydro sites". Factor This™ / Renewable Energy World. Retrieved 2025-07-16.

- ^ "Climate impacts on Latin American hydropower – Analysis". International Energy Agency. Retrieved 2025-07-16.

- ^ Asturias, F.; Enel Guatemala (2008). "Geothermal Resources and Development in Guatemala". Semantic Scholar. Retrieved 2025-07-16.

- ^ Caicedo, A. A. (1995). Miller, Ralph L.; Escalante, Gregorio; Reinemund, John A.; Bergin, Marion J. (eds.). Current Status of Geothermal Activities in Guatemala. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 247–255. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-79476-6_33. ISBN 978-3-642-79478-0. Retrieved 2025-07-16.

External links

- Gráficos do perfil energético da Guatemala, IRENA (em inglês)