Shinchō Kōki

Shinchō Kōki or Nobunaga Kōki (Japanese: 信長公記; lit. 'The Chronicle of Nobunaga') is a chronicle of Oda Nobunaga, a daimyo of Japan's Sengoku period. It is also called Shinchō Ki (信長記) or Nobunaga Ki. It was compiled after Nobunaga's death by Ōta Gyūichi (太田牛一), a vassal of Nobunaga, based on his notes and diary.[1][2]

The original was written by about 1598. It consists of a total of 16 volumes, including the main 15 volumes and the first volume. The main volumes covers the 15 years from 1568, when Nobunaga entered Kyoto with Ashikaga Yoshiaki, the 15th shogun of the Muromachi Shogunate (later banished from Kyoto by Nobunaga), to 1582, when he died in the Honnō-ji Incident. The first volume summarizes his life from his childhood, when he was called "Kipphōshi", until he went to Kyoto.[1][3] Each volume of the main series covers one year, and there are 15 volumes in total, covering 15 years of information. It is an excellent resource for learning about Oda Nobunaga, but research into him only began in earnest in Japan around 1965, which is a relatively recent development. So there are many things we don't understand.[4]

The chronicle contains not only subjects related to Nobunaga, but also murders, human trafficking, corruption, document forgery, and other street topics not directly related to Nobunaga, providing an insight into the public mood of the time.[5] Because it contains many stories that are unrelated to Nobunaga, and because the beginning of the first volume of the main story states, "This record is a record of the social conditions in which Oda Nobunaga lived from 1568 onwards,"[6] some have suggested that this document is a record of the society in which Nobunaga lived, and not just a record of Oda Nobunaga.[7]

Original, Manuscripts, and Publications

The book known today as Shinchō Kōki has many manuscripts and editions of the same original.[1][8] There are more than 60 known manuscripts, with various titles given to them, including Shinchō Ki (信長記), Azuchi Ki (安土記), Ōta Izuminokami Nikki (太田和泉守日記).[9] Some, such as the so-called Ikeda books handed down in the Ikeda clan, which was a family of daimyo, were commissioned by Ōta Gyūichi, who re-edited the contents to suit the client and transcribed it himself. Four sets of Shinchō Kōki in Gyūichi's own handwriting have now been identified, including the Ikeda book, and it is estimated that more than 70 sets existed in the past, including those written by people other than Gyūichi. However, as they are handwritten, their number is limited and only a few have survived. In particular, only two sets of Ōta Gyūichi's own handwritten books, complete with all volumes, have been found.[8] This figure includes those that do not have all the books and those that once existed but are now missing.[1][2]

It consists of 16 volumes, but the main volume is 15 volumes, and the first volume is thought to have been created later.[10] There is no consensus among researchers as to the origin of the story; some say it was added later to a 15-volume book, while others say it was originally written as separate stories that were then combined into one by a copyist. There is also a theory that it was originally composed of 16 volumes.[11] There are various versions of Shinchō Kōki, but the details of the order in which they were made, etc., are still under research and have not yet been clarified. However, the documents written by Gyūichi himself have one thing in common: they are all composed of 15 volumes.[8]

When the chronicle, rewritten in modern Japanese, was published in 1992, nearly 10,000 copies were sold by 2008, including a newly revised edition published in 2006, reflecting Nobunaga's popularity.[12]

An English translation was published in 2011 by Brill in cooperation with the Netherlands Association for Japanese Studies under the title The Chronicle of Lord Nobunaga. J.S.A. Elisonas and J.P. Lamers translated and edited the book.[13] It was also published in Ukraine in 2013.[14]

Original

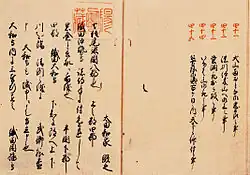

- Ikeda version(Ikeda book,池田版,池田本)[15][16][17][18][19]

- Written by Ōta Gyūichi. / Owned by Okayama University Library. / Important Cultural Property (Japan)

- It consists of 15 volumes. All volumes are available. Only Volume 12 is a manuscript.

- Due to its unique features, such as the mixture of Chinese and hiragana text and furigana written in red, it is considered to be the best condition book in the 15-volume composition.[20][17]

- The colophon of volume 13 lists the date, Gyūichi's name, and his age. "April 16, 1610, age 83"[21][22] At that time in Japan, the Lunar calendar was used and East Asian age reckoning system. The dates and ages have been converted to modern times. A direct English translation of the original text would be "February 23, 1610, age 84."

- In the same colophon, he writes about the writing process of the book, "The things I was writing in my diary came together naturally."[23]

- Kenkun version(Kenkun book,建勲神社本)[15][16][17][18][24]

- Written by Ōta Gyūichi. / Owned by Kenkun Shrine. / Important Cultural Property (Japan)

- It consists of 15 volumes. All volumes are available.

- 太田牛一旧記[8][25]

- Written by Ōta Gyūichi. / Owned by Oda Yumiko. She is the 17th head of the school that inherits the tea ceremony tradition of Oda Nagamasu, and the 16th head of the Oda clan.[26]

- This book did not have a title, so it has been called by various names.

- Only one volume. Contains only some episodes.

- 永禄十一年記[8][25]

- Written by Ōta Gyūichi. / Owned by Maeda Ikutokukai. The organization was created by the descendants of Maeda Toshiie, a vassal of Oda Nobunaga.

- Only one volume. Contains only some episodes.

Major manuscripts

- Maeda version(Sonkeikaku Library,Maeda book,前田本,尊経閣文庫本)

- Tenri version(天理本)

- Copy of original. / Owned by Tenri University.

- It consists of 16 volumes.

- This is a less well-researched version, but there are areas where the description differs significantly from the others. In particular, the contents of the first volume have changed, and significant additions have been made. Some believe that the additions may have been made by someone who read "Hoan Shinchō Ki" while making the manuscript, but others believe that it is an early manuscript before various details were omitted, since it contains more detailed descriptions than "Hoan Shinchō Ki".[30]

- Machida version(町田本)

- Copy of original. (The original is missing.) / Used as the basis for Wikisource.

- It consists of 16 volumes.

- Yomei version(陽明文庫本)

- Copy of original. (Original:Kenkun version.) / Owned by Konoe family. / Used as the basis for publication by Kadokawa Bunko.

- It consists of 16 volumes.

- Of the 16 volumes, this one is said to be in the best condition.

Derivative versions

Hoan-Shinchō-Ki

Oze Hoan read the Shincho-kōki and was dissatisfied that it was accurate but not interesting enough. Therefore, he created a book that incorporated Confucian values and incorporated many adaptations, and sold it widely as a woodblock print. This version was the first to be produced by letterpress printing. The exact date of writing is unknown (it is said to have been around 1611, but some say it was between 1604 and 1622). This is the "Hoan-Shinchō-Ki(甫庵信長記)." Although the content is based on Shincho-kōki, many adaptations have been added, making it less valuable as a material.[18]

Sōken Ki

During the Edo period, Toyama Nobuharu(遠山信春) attempted to restore the Hoan-Shinchō-Ki to its correct content as much as possible, since it had been heavily embellished and was of very low quality. This resulted in the creation of the "Sōken Ki (総見記)". It is said that it was created around 1685.The source material, Hoan-Shinchō-Ki, itself has many errors, and as time has passed since the original source material, Shincho-kōki, was created, there are many contents that cannot be confirmed. Reliability further deteriorated. It has several other names, and is sometimes called "Oda Gunki(織田軍記)" or "Oda Chiseiki(織田治世記)."[18]

Authorship

As a young man, Ōta Gyūichi served the Oda clan for his skill with the bow and arrow, and served Nobunaga as a fighter, but in later years his work as a government official became his main responsibility, including serving as a magistrate for land inspection. Before the Honnō-ji Incident, he held the position of deputy of Namazumi in the Ōmi Province, and after Nobunaga's death he became secretary to Niwa Nagahide. He then served Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Hideyori. He continued to write during the reign of Tokugawa Ieyasu, and there is a memo written in 1610 when he was 84 years old.[2][5]

Ōta Gyūichi was of a very penmanship nature and wrote down daily events in diaries and notes, which led to the compilation of the chronicle.[1][5]

After the death of Gyūichi, his descendants were largely split into two groups. One was the Asada Domain (Settsu Ota Clan), and the other was the Kaga Domain (Kaga Ota Clan).[31] The "Shinchō Kōki" and related documents were left in each family, and research is currently underway on them.[32][33] Documents handed down in the Settsu Ota Clan state that Gyūichi began writing when he was in his 70s.[34]

His lord, Nobunaga, is naturally written about favourably.[1] One episode that illustrates Nobunaga's kind-hearted side is the Yamanaka no Saru (Japanese: 山中の猿; lit. ' Yamanaka's Ape') episode. In the village of Yamanaka, there was a disabled beggar called Yamanaka no Saru. Nobunaga gave the villagers 10 pieces of cotton and asked them to build him a hut. Nobunaga further told his neighbours that he would be happy if they would share with him a harvest each year that would not be a burden on them.[5][35] However, he did not ignore what was inconvenient for Nobunaga, and on the other hand he also describes episodes that illustrate Nobunaga's misdeeds and brutality. As for the siege of Mount Hiei, the book describes the horrific scenes in a straightforward manner: Enryaku-jikonpon-chūdō and scriptures were burnt to the ground, and monks and non-monks, children, wise men and priests were decapitated. In another episode reads: The court ladies of the Azuchi Castle went on an excursion in Nobunaga's absence, but Nobunaga returned to the castle unexpectedly early. Knowing Nobunaga's character, these women were too frightened to return to the castle and asked the elder to apologise to him. This added fuel to the fire, and Nobunaga, furious as a flame, not only defeated them but also the elder.[1][5]

Accuracy

In historiography, biographies and war chronicles are regarded as secondary sources based on primary sources such as letters. In fact, "Shinchō Kōki" is a secondary source. However, the "Shinchō Kōki" was written by a contemporary of Nobunaga, and the author did not like to adapt the content of the book and described it as accurately as possible. For this reason, although "Shinchō Kōki" is a secondary source, it is treated as a reliable source, just like a primary historical source. Gyūichi was not so senior among Oda's vassals and the information he had access to was not perfect. Also, in manuscripts, the transcribers sometimes made mistakes, intentionally rewritten or added things that were not written down. However, among researchers, its credibility stands out compared to other similar documents and is considered trustworthy.[1][2][16][17][36][37][38]

Although this literature is considered reliable, it is not entirely free of errors. It remains a secondary source. Therefore, research should not rely entirely on this literature, but should compare it with other primary and secondary sources, as well as with other manuscripts of this book, to provide an appropriate source criticism.[39][16][40][17][41][36]

Title

Most of the extant editions have the external title Shinchō Ki, but to avoid confusion with Oze Hoan's kanazōshi of the same title, which is described below, the chronicle is generally called Shinchō Kōki. In contrast, Hoan's version is called Hoan Shinchō Ki, or simply Shinchō Ki.[2]

Influence

Shinchō Kōki is an indispensable historical book when talking about Oda Nobunaga. The life of Nobunaga, one of the most well-known figures in Japanese history, has been adapted into novels, manga, TV dramas, films, and video games many times in the past, and most of his life and episodes depicted in them are based on this book.[1][2]

Oze Hoan, a Confucian scholar of the Edo period, wrote a war chronicle called Hoan Shinchō Ki (甫庵信長記) based on Shinchō Kōki (信長公記), adding other anecdotes passed down in the public. Hoan was also the best-selling author of those days, having published other works such as Hoan Taikōki, a biography of Toyotomi Hideyoshi. It was published in the early Edo period (1611 or 1622) under the title Shinchō Ki. It then became a huge hit as a commercial publication and was reprinted throughout the Edo period. It is not highly valued as a historical document, as it contains many fictional stories. However, it was accepted by the masses because it was novelistic, written in an amusing manner, with Hoan's subjectivity and Confucian philosophy. On the other hand, Gyūichi's Shinchō ki was rarely seen by the general public throughout the Edo period. For reasons unknown, its publication as a printed book was prohibited by the Edo Shogunate and it only spread in manuscript form. Therefore, it was not Shinchō Kōki but the Hoan Shinchō Ki that was widely read by the common people, and its contents spread as a common knowledge among the people of the time. And even after the Meiji era, many people, including historians, have talked about Nobunaga until recently based on the knowledge of Hoan Shinchō Ki, which is different from historical facts.[1][2]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j 伊藤賀一 [in Japanese] (9 February 2023). "信長の人物像を形作った「信長公記」執筆の背景 本能寺での最期の様子も現場の侍女に聞き取り" [Background of the writing of "Shincho Koki" that shaped the character of Nobunaga Interviews with waiting maids at the scene of Nobunaga's final days at Honnō-ji.]. Toyo Keizai Online (in Japanese). Toyo Keizai. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g Mizuno, Seishiro (6 January 2018). "信長を知るにはとにかく『信長公記』を読むしかない" [The Only Way to Know Nobunaga is to Read "Shinchō Kōki" Anyway]. Chunichi Shimbun (in Japanese). Tokyo. Archived from the original on 15 July 2025. Retrieved 7 July 2023.

- ^ 信長公記. Kotobank (in Japanese). Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- ^ nakamuranastumi 2013, pp. 66–67.

- ^ a b c d e Wada, Yasuhiro (13 September 2018). "著者に聞く『信長公記—戦国覇者の一級史料』" [Interview with the Author, "Shinchō Kōki: First-Class Historical Documents of the Warring States Champions"]. web Chuko-Shinsho (in Japanese). Chuokoron-Shinsha. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- ^ Description in Source:永禄十一年戊辰以来織田弾正忠信長公の在世、且これを記す(Description in original document:永禄十一年戊辰以来織田弾正忠信長之御在世且記之)

- ^ nakamuranastumi 2013, pp. 80.

- ^ a b c d e nakamuranastumi 2013, p. 70.

- ^ Digitized versions are available on the Electronic Library of the Japanese National Diet Library.

- ^ 和田裕弘 (2018). 信長公記 —戦国覇者の一級史料. 中公新書. 中央公論新社. p. 4. ISBN 9784121025036.

- ^ nakamuranastumi 2013, pp. 75–77.

- ^ "「吾妻鏡」に「日本書記」... 史書の現代語版、出版続々" [Azuma Kagami, Nihon Shoki and yet more historical documents translated into modern Japanese.]. asahi.com BOOK (in Japanese). Asahi Shimbun. 11 July 2020. Archived from the original on 11 January 2008. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- ^ Ōta, Gyūichi (2011). Elisonas, J. S. A.; Lamers, J. P. (eds.). The Chronicle of Lord Nobunaga. Leiden and Boston: Brill. doi:10.1163/ej.9789004201620.i-510.8. ISBN 978-90-04-20162-0.

- ^ Ōta, Gyūichi (2013). Олександр, Коваленко (ed.). Самурайські хроніки : Ода Нобунага. Kyiv: Дух і літера. ISBN 9789663782935.

- ^ a b nakamuranastumi 2013.

- ^ a b c d 渡邊大門 [in Japanese] (2023-06-11). "織田信長の伝記『信長公記』は、本当に信頼していい史料なのだろうか" [Is the biography of Oda Nobunaga, "Shincho-kōki", really a reliable historical document?]. news.yahoo.co.jp (in Japanese). Yahoo! Japan. Archived from the original on 2024-11-29. Retrieved 2024-11-30.

- ^ a b c d e 渡邊大門 [in Japanese] (2022-06-17). "【戦国こぼれ話】織田信長の一代記『信長公記』とは、どういう史料なのだろうか" [What kind of historical document is the "Shincho-kōki" a chronicle of Oda Nobunaga's life?]. news.yahoo.co.jp (in Japanese). Yahoo! Japan. Archived from the original on 2024-11-29. Retrieved 2024-11-30.

- ^ a b c d 渡邊大門 [in Japanese] (2020-11-09). "【「麒麟がくる」コラム】織田信長の根本史料『信長公記』は、どういう史料なのだろうか?" [What kind of historical document is the "Shincho-kōki" the fundamental historical document of Oda Nobunaga?]. news.yahoo.co.jp (in Japanese). Yahoo! Japan. Archived from the original on 2024-11-29. Retrieved 2024-11-30.

- ^ "信長記〈自筆本/(第十二補配本)〉" [Shinchō ki]. kunishitei.bunka.go.jp (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs, Government of Japan. Retrieved 2025-04-02.

- ^ 朱筆の訓点(漢文を訓読するために書き入れる文字や符号)が施されており、また牛一自筆の冊が含まれると考えられ、もっとも善本であると指摘されている。

- ^ 慶長十五年二月廿三日 丁亥八十四歳

- ^ nakamuranastumi 2013, p. 67.

- ^ nakamuranastumi 2013, p. 72.

- ^ "信長公記〈自筆本/〉" [Shinchō Kōki]. kunishitei.bunka.go.jp (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs, Government of Japan. Retrieved 2025-04-02.

- ^ a b "レファレンス事例詳細「『信長公記』をできるだけ原本に近いもので見たい。」" [Reference Case Details I would like to see "The Chronicle of Nobunaga" in a text as close to the original as possible.]. Collaborative Reference Database (in Japanese). National Diet Library. Retrieved 2025-07-15.

- ^ "織田家第16代当主「信長没後、秀吉、家康に仕えた織田家の流転」" [The 16th head of the Oda family "After Nobunaga's death, the Oda family served Hideyoshi and Ieyasu, and the Oda family was in a state of flux."]. AERA DIFITAL (in Japanese). 週刊朝日. 17 June 2014. Archived from the original on 15 July 2025. Retrieved 15 July 2025.

- ^ "レファレンス事例詳細「『信長公記』の著者、太田牛一の著作で、前田元公爵家所蔵の「永禄十一年記」というものがあるらしいが、それを見たい。また、前田元公爵は加賀にゆかりの人物だと思うがその点も確認してほしい。」" [Reference Case Details I would like to see the "Eiroku Juinen-ki" (Record of the Year 11 of Eiroku), a work by Oota Ushiichi, the author of "Shinchō Kōki," which is owned by the Maeda Moto Duke family. I also believe that Maeda Moto Duke was a person with ties to Kaga, so I would like you to confirm this point.]. Collaborative Reference Database (in Japanese). National Diet Library. Retrieved 2025-07-10.

- ^ "利用案内" [Usage guide]. MAEDAIKUTOKUKAI FOUNDATION (in Japanese). Retrieved 2025-07-10.

- ^ 金子拓 [in Japanese] (2009). 織田信長という歴史 : 『信長記』の彼方へ. 勉誠出版. ISBN 9784585054207.

- ^ Mizuno, Seishiro (2 February 2018). "『信長公記 天理本 首巻』から新たな若き信長像が見えてくる" [A New Image of the Young Nobunaga Emerges from "Shinchō Kōki, Tenri-bon, first volume"]. Chunichi Shimbun (in Japanese). Tokyo. Archived from the original on 23 July 2025. Retrieved 23 July 2025.

- ^ 現代語訳信長公記(全)ちくま学芸文庫 解説 『信長公記』と作者太田牛一 『現代語訳 信長公記(全)』文庫版解説 金子拓 at the Wayback Machine (archived 2025-04-23)

- ^ 金子拓; 黒嶋敏 (2008-01-01). "大田家文書の調査・撮影". 東京大学史料編纂所報 (in Japanese). 43. 東京大学史料編纂所: 56.

- ^ 金子拓; 黒嶋敏 (2008-01-01). "太田家文書の調査・撮影". 東京大学史料編纂所報 (in Japanese). 43. 東京大学史料編纂所: 80.

- ^ nakamuranastumi 2013, pp. 71.

- ^ 石川拓治 [in Japanese] (17 March 2020). "信長見聞録 天下人の実像 - 第十五章 山中の猿" [Nobunaga Observations: The Realities of the Ruler of Japan - Chapter 15: Yamanaka no Saru]. GOETHE (in Japanese). Gentosha. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- ^ a b 渡邊大門 [in Japanese] (2021-12-18). "【戦国こぼれ話】一次史料と二次史料とは? 戦国時代の新説に注意すべきポイント" [[Sengoku Trivia] What are primary and secondary sources? Things to be aware of when considering new theories about the Sengoku period]. news.yahoo.co.jp (in Japanese). Yahoo! Japan. Archived from the original on 2025-07-15. Retrieved 2025-07-15.

- ^ Brownlee, John S. (1991). Political Thought in Japanese Historical Writing: From Kojiki (712) to Tokushi Yoron (1712). Wilfrid Laurier University Press. p. 140. ISBN 0-88920-997-9.

- ^ Sansom, George Bailey (1961). A History of Japan, 1334-1615. Stanford University Press. p. 423. ISBN 0-8047-0525-9.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ 自筆による原本は、池田家本(岡山大学池田家文庫所蔵)のほかに、複数伝わっている。また、多くの写本が伝わっており、研究の際はそれぞれを突き合わせて用いられることが多い。牛一が『信長公記』を執筆した態度は、「私作、私語に非ず」という客観的な姿勢だった。それゆえに良質な編纂物として史料的な価値も高いが、二次史料であることには変わりがない。全面的に依拠するのではなく、一次史料と照合して用いるべきだろう。

- ^ 『信長公記』は信長研究で欠かすことができない史料であり、二次史料とはいえ、おおむね記事の内容は信頼できると評価されている。信長研究の根本史料であることは疑いない。ただし、成立年は信長の死後から21年が経過しているので、いかに牛一のずば抜けた記憶力やメモがあったとはいえ、誤りや記憶違いもあると危惧される。したがって、必ずしも『信長公記』は万能とは言えないので、史料批判を十分に行って使用する必要がある。利用に際しては慎重さが必要で、一次史料(同時代の古文書や書状など)との照合が必要なのだ。

- ^ 一般的に、二次史料は時間が経過してから作成されるので、史料的な性質が劣るとされている。むろん、史料批判は必要である。しかし、良質な史料があるのも事実である。たとえば、太田牛一が著した織田信長の一代記『信長公記』は、史実と照らし合わせても、誤りが少ないとされている。二次史料は、目的があって作成される。おおむね先祖の功績を称えるケースが多い。したがって、都合の悪いことが書かれなかったり、活躍ぶりを大袈裟に表現することがある。史実を捻じ曲げて書くことも、大いにある話である。二次史料の作成に際しては、残った一次史料はもとより、口伝、関係者の聞き取りなど多種多様である。口伝や聞き取りの場合は、記憶違いなどによる誤りも少なくない。つまり、二次史料は単体で用いて史実を確定するには向かない史料であり、あくまで一次史料に基づくべきであろう。50年も100年(あるいはもっと前)も前のことを正確に記すのは、至難の業である。

List of references

- "Shinchō Kōki". History of Japan (CD-ROM version) 日本史事典(三訂版) (CD-ROM版) (3rd ed.). Ōbunsha.

- "Welcome to the world of the account of 'Shinchou Kouki'" (defunct; link via the Wayback Machine)

- 中村名津美 (2013-12-25). "太田牛一『信長公記』編纂過程の研究" (PDF). 龍谷大学大学院文学研究科紀要 (in Japanese). 35. 龍谷大学大学院文学研究科紀要編集委員会: 66–82. ISSN 1348-267X.

External links

Can be viewed

- Okayama University Library Archives Gallery - Shinchō Ki Ikeda version

- Shinchō Kōki(wikisource) - Shinchō Kōki Machida version

Unable to view

- Cultural Heritage Database - About the documents held by Kenkun version

- Maeda Ikutokukai - Shinchō Ki Maeda version

- Yomei Library - Shinchō Ki Yomei version