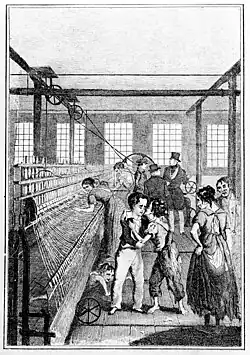

Child labour in the British Industrial Revolution

When the Industrial Revolution began, industrialists used children as a workforce.[1] Children as young as four and five years old often worked the same 12-hour shifts as adults, although some worked shifts as long as 14 hours.[2][3][4][5] By the 1820s, 50% of English workers were under the age of 20.[1][6] Many workers under 12 were employed by their parents (not directly by the business owner), and worked alongside parents in support roles. According to the Census of 1851, the majority of working children were not in factories, but were filling traditional roles, especially farming and domestic service. The 1851 Census shows that 98 per cent of children under the age of 10 did not work regularly for wages. Of children aged 10 to 14, 72% were either attending school or unoccupied.[7]

Consequences

Child labour brought down adult wages due to competition and brought no net benefit to working-class families.[8]

Child labourers never had more than three years of schooling.[3]

Child labourers developed occupational diseases later in life. Breathing in coal dust caused child labourers to later develop lung diseases.[3] Children who worked as chimney sweeps later developed chimney sweeps' carcinoma, a squamous cell carcinoma of the scrotum. The disease was recognised by Percivall Pott and was the first reported form of occupational cancer.[9][10]

Men who had been child labourers were often unable to raise their own children without condemning them to child labour as well. This deleterious cycle not only impacted the health of current generations, but also future generations.[8]

Statistics

From 1800 to 1850, children made up 20 to 50% of the mining workforce.[1] In 1842, children made up over 25% of all mining workers.[3]

Children made up 33% of factory workers.[3]

In 1819, 4.5% of all cotton workers were under the age of 10 and 54.5% were under the age of 19.[11] In 1833, children made up around 33% to 66% of all workers in textile mills.[3] In the same year, 10% to 20% of all workers in cotton, wool, flax, and silk mills were under the age of 13, and 23% to 57% of all workers in those same mills were 13 to 18 years old. Between 1/6 and 1/5 of all workers in textile towns were under the age of 14 in the same year.[11]

In 1841, the most three common jobs for boys under 20 were agricultural labourer (196,640), domestic servant (90,464), and cotton manufacturer (44,833). The three most common jobs for girls under 20 were domestic servant (346,079), cotton manufacturer (62,131), and dressmaker (22,174). The most common jobs for boys under 15 were agricultural labourer (82,259), messenger (43,922), and cotton manufacturer (33,228). The most common jobs for girls under 15 were domestic servant (58,933), cotton manufacturer (37,058), and indoor farm servant (12,809).[11]

Orphans

Orphans were frequent victims of exploitation. Factory owners could justify not paying orphans because they provided them with clothing, food, and shelter,[4][11] even though these things were likely to be substandard.[4] Orphans, and poor children, worked as chimney sweeps.[10] An orphan also might be trained to be a shoe black by a charitable organization.[3]

Child labour laws

- The Health and Morals of Apprentices Act 1802 stipulated that child apprentices should not work more than 12 hours a day, must be given a basic education, and must attend church services church twice a month.[3] The law was ineffective because it failed to provide for enforcement.[12]

- The Cotton Mills and Factories Act 1819 limited work to children 9 years old or older, and children could not work more than 12 hours a day if they were not 16 years old or older.[3][11] It also set possible working hours as between 6 am and 9 pm.[3]

- The 1833 Factory Act stipulated that no child under the age of 9 could be legally employed, children 9 to 13 years old could not work more than 8 hours, and children 14 to 18 could not work more than 12 hours a day, children could not work at night, children needed to attend a minimum of 2 hours of education a day, and employers needed age certificates for their workers.[3][13][4] It also appointed four factory inspectors to enforce the law.[13] A report by the factory inspectors in 1835 stated that child labour in child factory in textile factories had decreased by 50%.[14]

- Multiple chimney sweepers acts were passed in an attempt to protect child workers. The Chimney Sweepers Act 1788 set a minimum age limit of 8 and required weekly baths for children. The Chimney Sweepers Act 1834 limited the minimum age of chimney sweeps to 14 and mandated a limit on the number of apprentices a master chimney sweep could have. The Chimney Sweepers and Chimneys Regulation Act 1840 then set a minimum age limit of 16 on chimney sweep apprentices.[10][9] Others included the Chimney Sweepers Regulation Act 1864 and Chimney Sweepers Act 1875.

- The Mines and Collieries Act 1842 stipulated that no child under 10 years old could be employed in any underground work.[3]

See also

- Economy, industry, and trade of the Victorian era

- Life in Great Britain during the Industrial Revolution

References

- ^ a b c Michon, Heather (2021-03-21). "The History of Child Labor in England: From the Industrial Revolution to Reforms and Changing Attitudes". The Economic Historian. Archived from the original on 2024-12-04. Retrieved 2024-11-30.

- ^ Kirby, Peter (2014). Child Workers and Industrial Health in Britain, 1780-1850. Boydell & Brewer.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Cartwright, Mark (2023-04-12). "Child Labour in the British Industrial Revolution". World History Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 2024-12-02. Retrieved 2024-11-30.

- ^ a b c d "Children in the Industrial Revolution". historylearning.com. Archived from the original on 2024-12-04. Retrieved 2024-12-02.

- ^ Collyer, Robert (1908). Some memories. Boston, American Unitarian association. p. 15.

- ^ Ciocan, Alin (2024-05-31). "UK Child Labour Laws: A Historical Overview". Labour Laws UK. Retrieved 2024-11-30.

- ^ Pamela Horn, Children's work and welfare, 1780-1890 (Cambridge UP. 1995.) pp. 5, 7

- ^ a b Humphries, Jane. "Childhood and Child Labour in the British Industrial Revolution". assets.cambridge.org. Archived from the original on 2024-12-04. Retrieved 2024-12-02.

- ^ a b Dronsfield, Alan (1 March 2006). "Percivall Pott, chimney sweeps and cancer". Education in Chemistry. Vol. 43, no. 2. Royal Society of Chemistry. pp. 40–42, 48. Retrieved 3 August 2025.

- ^ a b c Benmoussa, Nadia; Rebibo, John-David; Conan, Patrick; Charlier, Philippe (1 March 2019). "Chimney-sweeps' cancer—early proof of environmentally driven tumourigenicity". The Lancet Oncology. 20 (3): 338. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30106-8. ISSN 1470-2045. PMID 30842048. S2CID 73485478.

- ^ a b c d e "HIST363: Child Labor during the British Industrial Revolution | Saylor Academy". Saylor Academy. Retrieved 2024-12-05.

- ^ "Factory Act | 1833, Significance, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2024-12-01.

- ^ a b Archives, The National. "The National Archives - Homepage". The National Archives. Archived from the original on 2024-12-01. Retrieved 2024-12-01.

- ^ Ciocan, Alin (2024-07-09). "The Evolution of Child Labour Laws in the UK: A Comprehensive Historical Guide". Labour Laws UK. Retrieved 2024-12-01.

Further reading

- Anderson, Elisabeth Agents of Reform: Child Labor and the Origins of the Welfare State (Princeton University Press, 2021)

- Auerbach, Alexander Josef. " 'In the courts and alleys': The enforcement of the laws on children's education and labor in London, 1870–1904" (PhD dissertation, Emory University; ProQuest Dissertations & Theses, 2001. 3018784).

- Battiscombe, Georgina. Shaftesbury: A Biography of the Seventh Earl, 1801-1885 (Constable, 1974) pp. 137-154.

- Bolin-Hort, P. Work, family and the state: child labour and the organization of production in the British cotton industry, 1780–1840 (Lund, 1989).

- Bready, J. Wesley. Lord Shaftesbury and social-industrial progress (1926) online

- "Child Labour during the Industrial Revolution" in Encyclopedia of British History; comprehensive coverage

- Collier, Martin and Philip Pedley. Britain 1815-51: Protest and Reform (Heinemann, 2001) pp.46–54.

- Cruickshank, Marjorie. Children and Industry (Manchester UP, 1981), focus on textiles.

- Cunningham, Hugh. "The employment and unemployment of children in England c. 1680-1851." Past & Present 126 (1990): 115-150. JSTOR 650811

- Honeyman, Katrina. Child workers in England, 1780–1820: parish apprentices and the making of the early industrial labour force (Routledge, 2016).

- Horn, Pamela. Children's work and welfare, 1780-1890 (Cambridge UP. 1995.)

- Humphries, Jane. Childhood and Child Labour in the British Industrial Revolution (Cambridge Studies in Economic History) (2011) online

- Humphries, Jane. "Childhood and child labour in the British industrial revolution 1." Economic History Review 66.2 (2013): 395-418. online

- Hunt, E.H. British Labour History, 1815–1914 (Humanities Press, 1981), pp.9-17, With statistics on occupation for boys and girls in 1851, 1881 and 1911. online

- Hutchins, B. L.; Harrison, A. (1911). A History of Factory Legislation. P. S. King & Son.

- Kirby, Peter. Child Labour in Britain, 1750-1870 (2003) online

- Margaret McMillan (1907), Labour and Childhood, London: Swan Sonnenschein & Co., Wikidata Q107325671

- Lichtenstein, Matty R. "Agents of reform: Child labor and the origins of the welfare state" British Journal of Sociology (2024) 75#4 pp.668-670.

- Nardinelli, Clark. "Child Labor and the Factory Acts" Journal of Economic History 40#4 (1980), pp. 739-755 online argues it benefitted the family

- Tuttle, Carolyn. Hard at Work in Factories and Mines: The Economics of Child Labour During the British Industrial Revolution (1999); A standard scholarly history.

- Tuttle, Carolyn. " Children at work in the British Industrial Revolution" (PhD dissertation, Northwestern University; ProQuest Dissertations & Theses, 1986. 8621879).

Primary sources

- Cole, G. D. H., and A. W. Filson, eds. "The Factory Movement, 1815–1850." in British Working Class Movements: Select Documents 1789–1875 (Palgrave Macmillan UK, 1965) pp.311–330. preview

- Pike, E. Royston, ed. Human Documents of the Industrial Revolution in Britain (Taylor & Francis, 2005) introductions and 250 short excerpts; online