Chalcedonian Schism

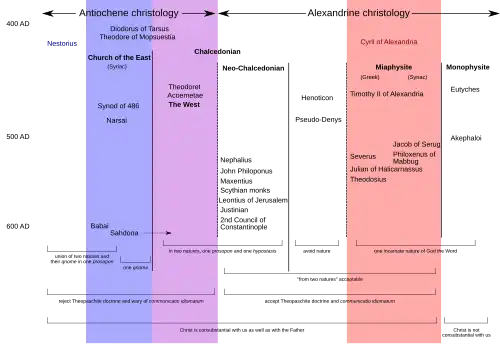

Spectrum of 5th to 7th century Christological views | |

| Date | 1 November 451 – present |

|---|---|

| Type | Christian schism |

| Cause | Council of Chalcedon Dispute over whether Christ has one nature or two natures |

| Participants | |

| Outcome | Separation of the Oriental Orthodox Churches from the Great Church |

The Chalcedonian Schism, also known as the Monophysite Schism,[note 1] is the break of communion between the Oriental Orthodox Churches and the Great Church (which later became the Eastern Orthodox Church and Catholic Church) in the aftermath of the Council of Chalcedon.[3] Although the bishops at Chalcedon greatly respected Cyril of Alexandria and used his writings as a benchmark for orthodoxy,[4] opponents of the council believed that the Chalcedonian Definition, which states that Christ is "acknowledged in Two Natures", was too close to Nestorianism and contradicts Cyril's formula "one nature of God the Word incarnate".[note 2] The Council had also deposed the Pope of Alexandria, Dioscorus, but his supporters continued to consider him their rightful Pope, refusing to recognise the council-appointed Proterius.

The anti-Chalcedonian strongholds were in Egypt, Palestine and later Syria.[7] Over the next century, their communities gradually separated from the official church of the Byzantine Empire, eventually becoming the Oriental Orthodox Churches.[1] The imperial government made many attempts to mend the schism, generally by trying to compromise between the two positions, but these attempts only created further heresies and schisms. The Arab conquests of the Levant and of Egypt in the 7th century fossilised the schism, but ecumenical dialogue between Chalcedonian and non-Chalcedonian Christians has been renewed since the 20th century.

Background

Council of Ephesus

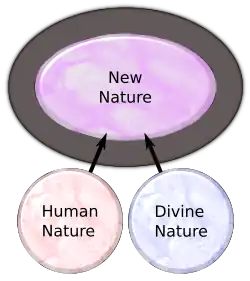

Leading up to the 430s, the theological Schools of Alexandria and of Antioch had been developing slightly different views on Christology. Antiochene theologians such as Theodore of Mopsuestia and Theodoret of Cyrrhus had a "Word-man" Christology, or "Christology from below", which placed more emphasis on Christ's humanity and free will, and the distinction of his two natures. In their view, Jesus, the man (homo assumptus) to whom God the Word was conjoined, atoned for the sins of mankind through his perfect life and his sacrifice on the cross, after which God raised him up to heaven "as a pledge of the salvation of all humanity". In contrast, Alexandrian theologians such as Athanasius and Cyril of Alexandria had a "Word-flesh" Christology, or "Christology from above", which placed more emphasis on Christ's divinity and its abolute unity with his humanity. In their view, the Word became flesh, not merely by indwelling a man but through a hypostatic union. He then "tasted death in the flesh" on the cross and rose from the dead, thus saving humanity not by a moral example but by being incarnate for our sake, since "what is not assumed is not saved".[8]

Additionally, See of Rome's interpretation of its relationship to the other patriarchates (Constantinople, Alexandria, and Antioch[note 3]) was increasingly diverging from their own. While the other patriarchates saw themselves as colleagues based on their autocephalous relationship to each other, the Popes of Rome believed that their position as "first among equals" and as the successors of Saint Peter gave them authority over the entire church.[9]

These divisions came to a head in April 428, when Theodosius II appointed Nestorius, a monk from Antioch, to be the Patriarch of Constantinople. Nestorius immediately outraged the population by preaching against the use of the title Theotokos (Mother of God) for the Virgin Mary, arguing that Mary only gave birth to Christ's humanity, not his divinity.[10] This was despite the title having a large role in popular piety, and having been used by previous theologians such as Athanasius, the Cappadocian Fathers, John Chrysostom, and even (with reservations) by Nestorius' own teacher Theodore of Mopsuestia.[11][note 4] Nestorius' main opponent was Cyril, the Patriarch of Alexandria, who wrote him three letters. In the second letter, written in February 430, Cyril criticised Nestorius' theology, arguing that the Word was not united to a man "merely as a result of will or good pleasure", but "became flesh" as is written in John 1:14, and therefore the Virgin who bore the Word in his human nature can rightly be called the Theotokos.[13] Cyril was more aggressive in his third letter to Nestorius, which further defined his theology and ended with 12 prepositions Cyril called on Nestorius to anathematize.[14]

Instead of cornering Nestorius, Cyril's third letter brought his own orthodoxy into question. Theodoret of Cyrrhus and Andrew of Samosata wrote rebuttals of Cyril's 12 anathemas, to which he responded with counter-rebuttals. Both Cyril and Nestorius wrote to Pope Celestine I of Rome for support, but he sided with Cyril. To settle the dispute, Theodosius II convened the Council of Ephesus. On 22 June 431, the council condemned Nestorius as "the new Judas" and deposed him.[13] However, the dispute was not over, as John of Antioch arrived 4 days later with a group of Syrian bishops, only to find the council already finished and Nestorius condemned. He then excommunicated Cyril and everyone who had agreed to his 12 Anathemas. In April 433, Cyril and John reconciled with one another by both agreeing to the Formula of Reunion, which stated that Christ was "of two natures" (Greek: Δύο φύσεων ἕνωσις), in a "union without confusion" (Greek: ἀσυγχύτου ἑνώσεως), and consubstantial both with the Father and with humanity.[15][note 5]

Some of Cyril's supporters believed that the Formula of Reunion was not compatible with the 12 Anathemas, and that by accepting the former he had denounced the latter. Cyril sent many letters to these people, explaining that the Formula of Reunion was compatible with the 12 Anathemas and that he still stood by both.[16] In some of these letters, like his second letter to Succensus, Bishop of Diocaesarea, he argued that Christ could be thought of as two natures after his Incarnation as long as the two natures are divided "in thought only" (Greek: τῆ θεωρία μόνη), the way a human body and soul can be thought of as different but are in fact just one person.[17]

Second Council of Ephesus

After the Council of Ephesus, there was peace for about a decade, but theological controversies soon brewed up again in the 440s. In 447, an archimandrite in Constantinople named Eutyches, apparently misunderstanding Cyril's "one nature of God the Word incarnate" formula, began preaching that Christ has only one nature, and that his humanity was so completely "deified" by his divinity that he was not consubstantial with mankind.[18][19] Bishop Eusebius of Dorylaeum, who had been one of the first people to denounce Nestorius, presented a bill of indictment formally accusing Eutyches of heresy.[20] In November 448, Eutyches was tried by the Home Synod of Constantinople, presided by the Patriarch Flavian of Constantinople. After he refused to confess two natures after the Incarnation, the synod excommunicated Eutyches, judging that he had overreacted to Nestorianism and fallen into the opposite heresy.[19]

Flavian sent a report of Eutyches' trial to Pope Leo I, who responded with a statement of faith known as Leo's Tome. Meanwhile, Eutyches did not accept his condemnation quietly. He appealed to Emperor Theodosius II, as well as to Pope Dioscorus I of Alexandria, who had succeeded Cyril. Through the influence of Chrysaphius, Eutyches' godson and a powerful eunuch in the imperial court, Theodosius convoked another council at Ephesus to re-try Eutyches, this time presided by Dioscorus. This Second Council of Ephesus began on 8 August 449, and was attended by Flavian, Juvenal of Jerusalem, Domnus of Antioch, and about 130 other bishops. During this council, the Roman papal legates repeatedly called for Leo's Tome to be read, but Dioscorus intentionally ignored them. After having the acts of the 448 Home Synod read, Dioscorus declared that Flavian and Eusebius were guilty of innovation, and pronounced them deposed.[21] The council immediately broke into chaos, with armed monks and soldiers charging into the church. Flavian was beaten so badly he died of his injuries; according to eyewitness Diogenes of Cyzicus, an archimandrite named Barsauma stood by and cried "Strike him dead!" as his monks beat Flavian. Although the acts of the council recorded that the bishops present assented to Eusebius and Flavian's depositions, two years later they would claim that Dioscorus used armed monks and soldiers to threaten them, had them sign blank papers, and forged statements from them.

Despite Dioscorus' attempts to stop him, the papal legate Hilarius escaped Ephesus with great difficulty and made it back to Rome, bringing with him an Flavian had written to Leo shortly before his death. Leo was outraged by the Second Council of Ephesus, dubbing it a latrocinium ("synod of robbers") in a letter to Pulcheria. He wrote many appeals to the emperor, the court, the clergy and the people of Constantinople urging them not to accept it, but Theodosius refused to reconsider its decrees.[22][23]

Council of Chalcedon

In July 450, Theodosius II died in a hunting accident and was succeeded by his sister Pulcheria. She immediately had Chrysaphius executed, and married the general Marcian on the condition that he allow her to keep her vow of chastity. She also reached out to Leo, who demanded the acceptance of his Tome as a condition for re-establishing communion. Anatolius and Maximus (who had been installed by Dioscorus as the patriarchs of Constantinople and Antioch respectively) assented, and Ephesus II rapidly lost support. The main criticism against it was not its theology, but the brutal methods with which it was conducted.[22] In 451, the new emperor Marcian summoned another council in Chalcedon, "to end the disputations and settle the true faith more clearly and for all time."[24]

The Council of Chalcedon was attended by 520 bishops,[note 6] of whom 124 had been present at Ephesus II. In its second session (held on 10 October), they read Leo's Tome and the letters of Cyril, and, after vigorous debate, they declared them to be in agreement with one another, thus accepting Leo's Tome as orthodox. Cyril's third letter to Nestorius, which contained his 12 Anathemas and his most strongly miaphysite statements, was notably absent from the discussion.[26] The council's third session on 13 October was a trial of Dioscorus. Several accusers, most of whom had been Cyril's family or friends, listed their grievances against Dioscorus' conduct. He was repeatedly summoned to defend himself, but claimed he was under house arrest and could not come to the council, so he was deposed in absentia.[27] Importantly, this deposition was not for heresy, but for "grave administrative errors" like allowing Flavian's death.[28]

In the fifth session, the imperial officials asked the bishops to compose a Definition of Faith, which would become the Chalcedonian Definition. The bishops were reluctant to do so, since Canon 7 of Ephesus forbade the use of new creeds,[29][28] but eventually they wrote a draft that contained the Cyrillian phrase "of two natures" (Greek: ἐκ δύο φύσεων). Although the vast majority of the council was pleased with this draft, the papal legates protested and threatened to go home. The bishops then wrote another version, using "in two natures" (Greek: ἐν δύο φύσεσιν) instead. Many of the bishops were uncomfortable with this clause; only two years before, at Ephesus II, they had shouted "Anathema to whoever says two natures after the incarnation", and called for those who divide Christ in two to be cut into pieces.[30] These bishops acquiesced only after the imperial officals reminded them that they had already accepted the orthodoxy of Leo's Tome, which said that "there are two natures in Christ, united without confusion, change or separation in the one only-begotten Son our Saviour".[31]

The Chalcedonian Definition was largely based on the 433 Formula of Reunion, with some additions from Cyril's other letters.[32] It attempted to define the via media between the opposite heresies of Eutyches and Nestorius. For example, it used the phrase "unconfusedly, unchangeably, indivisibly, inseparably" (Greek: ἀσυγχύτως, ἀτρέπτως, ἀδιαιρέτως, ἀχωρίστως); the first two words were directed at Eutyches, and the second two at Nestorius.[33]

Aftermath

Immediate

The Council of Chalcedon faced immediate opposition in the eastern parts of the Empire. Syria was divided between pro- and anti-Chalcedonians, while in Egypt the vast majority were against Chalcedon.[34] They felt that Leo's Tome and the Chalcedonian Definition, despite condemning Nestorius in name, had restored his heretical teachings by describing Christ as "in two natures". Rumours about Chalcedon spread in Egypt, claiming that it had vindicated Nestorius' teachings, that it taught that the one crucified was not God, that it was not scriptural, and that the Jews were delighted to hear of it.[note 7] Leo complained that Greek translations of his Tome misleadingly made him speak of "two persons". These rumours were not helped by the fact that Chalcedon had restored two Nestorian bishops to their sees, Theodoret of Cyrrhus and Ibas of Edessa, although that was on the condition that they anathematise Nestorius, which they did. The opposition to Chalcedon initially included respectable monastic figures like Saint Gerasimus, Saint Gerontius (former confidant of Melania the Younger), Peter the Iberian, and the former empress Aelia Eudocia.[36]

Patriarch Juvenal of Jerusalem, who was originally Dioscorus' ally but switched sides at Chalcedon, returned to violent protests in Palestine which temporarily drove him out of his see. In Egypt, a mob set fire to the Serapeum, killing many soldiers who were inside. At first, Marcian and Pulcheria tried using diplomacy, writing letters directly to the rebels, but when that did not work they sent troops to suppress them.[37] In Egypt, those troops raped women, further galvanising Egyptian opposition to Chalcedon.[note 8]

Of the 20 Egyptian bishops at Chalcedon, 13 refused to depose Dioscorus. They argued that they would be killed in Egypt if they turned on Dioscorus,[note 9] and cited Canon 6 of Nicea, which states that bishops of Egypt should be under the authority of the Pope of Alexandria. However, four of the Egyptian bishops joined the council in condemning Dioscorus. Those four consecrated his former arch-priest Proterius as the next Pope of Alexandria. He had been known for his strong Cyrillian position, to the extent that Leo even doubted his orthodoxy.[36] But on Holy Thursday of 457, soon after Marcian's death, Proterius was lynched by a mob of anti-Chalcedonians while celebrating the eucharist. Two anti-Chalcedonian bishops (one of whom was Peter the Iberian) then consecrated Timothy Ailuros in the Caesareum Church as their new Pope.

Marcian's successor Leo was unsure of how to deal with Timothy, as he did not want to use force like Marcian had. Instead, he held a "plebiscite" in 457, asking every bishop in the empire (as well as respected monks like Simeon Stylites) for their opinions on Timothy's legitimacy. The overwhelming majority of the responses, which are recorded in the Codex Encyclius, were against Timothy and pro-Chalcedon. Timothy was approached in person and asked to follow the majority of the episcopate, but he refused. He was then arrested in the middle of a popular insurrection, which the army violently put down by killing 10,000 people.[40] His successor, Timothy Salophakiolos, was well-liked by both sides of the schism, and did his best to reconcile them to each other. However, the non-Chalcedonians continued to consider Timothy Ailuros their Pope.

One sticking point between Chalcedonians and Miaphysites was Theopaschism: the belief that God the Son suffered in the flesh on the cross. Theopaschism had been affirmed in Cyril's 12th anathema, in Leo's Tome, and in the Nicene Creed.[41][note 10] However, several Chalcedonian writers, like Theodoret, Gennadius, Macedonius, and the Acoemetae, were unwilling or reluctant to confess it.[42] In 469, the magister militum per Orientem Zeno appointed the non-Chalcedonian Peter the Fuller as Patriarch of Antioch. Peter the Fuller added a theopaschite statement to the Trisagion, changing "Holy God, Holy Mighty, Holy Immortal, have mercy on us" to "Holy God, Holy Mighty, Holy Immortal, who was crucified for us, have mercy on us".[43]

Zeno became emperor in 474, but the next year he was ousted by Basiliscus. He tried to appease the Miaphysites by restoring Timothy Ailuros and Peter the Fuller (both of whom were in exile) to their patriarchates. When Timothy arrived in Constantinople from his exile in Cherson, he was greeted by the populace and Basiliscus himself, then paraded by Alexandrian seamen to the "Great Church" (later the Hagia Sophia) on a donkey, as though he were Jesus himself. He then entered Alexandria to popular cries of "Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord". On 9 April 475, Basiliscus published an encyclical which praised the first three ecumenical councils, but condemned Chalcedon and Leo's Tome. These measures were widely popular in Egypt and Syria, but equally unpopular in Constantinople and Rome. The Patriarch of Constantinople, Acacius, refused to sign the encyclical, and Daniel the Stylite descended from his pillar for the first time in 33 years to chastise Basiliscus as a "new Diocletian". Faced by all this, Basiliscus backtracked and published a counter-encyclical, which made no mention of Chalcedon.[44]

Acacian Schism

In 476, Zeno was restored as emperor, and all of Basiliscus' acts were abrogated. On 28 July 482, on the advice of Acacius, Zeno published the Henotikon in an attempt to mend the schism. It accepted the orthodoxy of Cyril's 12 Anathemas in his third letter to Nestorius (which was ignored at Chalcedon), but also that of the Formula of Reunion in his letter to John of Antioch (which was an embarrassment to anti-Chalcedonians).[7] It neither endorsed nor condemned Chalcedon. The eastern patriarchs and bishops were required to sign it in order to keep their sees, so the majority did. But in Rome, Pope Felix III rejected it. He excommunicated Acacius and everyone who had signed the Henotikon, beginning the Acacian Schism. The Henotikon remained the offical policy of the empire for the rest of Zeno's reign, as well as that of his successor Anastasius.

The Henotikon's vague wording meant that pro- and anti-Chalcedonians continued to quarrel, despite both sides accepting the Henotikon. Evagrius wrote that "in those days, the council of Chalcedon was neither openly proclaimed in the most holy churches, nor was it rejected by all; each bishop acted according to his conviction". Anti-Chalcedonians interpreted a specific statement in the Henotikon[note 11] as a condemnation of Chalcedon, while Chalcedonians disagreed with that interpretation. In 490, the openly Chalcedonian Patriarch Euphemius of Constantinople broke communion with Alexandria, and so did Flavian of Antioch and Elias of Jerusalem. They tried to re-establish communion with Rome, but Pope Gelasius unrealistically demanded that they remove Acacius from the diptychs exclusively on the basis of his deposition by Rome.[45]

Around this time, Severus of Antioch, a convert from paganism and a brilliant theologian educated in rhetoric, Greek, philosophy and law, was becoming the main spokesman of the anti-Chalcedonians. In 509, he was expelled from Antioch by Chalcedonians, and took refuge in Constantinople. There, he wrote a typos, circulated by Anastasius, that presented itself as an interpretation of the Henotikon, but condemned Chalcedon and Leo's Tome. He also promoted the theopaschite addition to the Trisagion. When it was chanted for the first time at the Great Church in 512, Chalcedonians rioted, overthrew statues of Anastasius, and violently attacked Miaphysites. Anastasius calmed them by appearing before the crowds at the Hippodrome in mourning clothes and without his crown, and offering to resign as emperor.[46]

Also in 512, the Miaphysites secured Severus' ordination as Patriarch of Antioch. Anastasius, who hoped to use the Henotikon to bridge Chalcedonians and Miaphysites, was frustrated by Severus' persistent attempts to make it an anti-Chalcedonian document.[47] By the time Anastasius died in 518, it was clear that the Henotikon had failed to live up to its name, which means "unifier". The next emperor, Justin I, therefore abandoned it, restored Chalcedon, and expelled Miaphysite bishops (including Severus) from every province except Egypt. He and his two consuls, Vitalian and Justinian, sought reunion with Rome at any cost. Pope Hormisdas sent them the Libellus Hormisdae, a list people Rome wanted condemned that included Acacius, his four successors, and the emperors Zeno and Anastasius. The patriarch John signed it on 28 March 519, ending the Acacian Schism.[48]

Justinian

.jpg)

March 519 also saw the arrival in Constantinople of a group of Scythian monks from modern Dobruja, headed by John Maxentius. These monks held a Christology that was both Cyrillian and Chalcedonian. Importantly, they promoted the theopaschite formula "One of the Holy Trinity suffered in the flesh" (which had been used in 435 by Proclus in his Tome to the Armenians). The Scythian monks believed that, since Christ's hypostasis which suffered in the flesh was the pre-existent hypostasis of the Logos, and since there is one Son, not two, their theopaschite formula was a necessary litmus test for orthodoxy. After campaigning unsuccessfully for the adoption of their formula in Constantinople, they also went to Rome to present their case before Pope Hormisdas. Although they met support there (such as from Fulgentius of Ruspe and their fellow Scythian Dionysius Exiguus), Hormisdas eventually decided that their theopaschite formula was unnecessary and expelled them from Rome. However, they won the support of Justinian, who became convinced that their formula was the key to religious unity in the empire.[49]

Justinian was an ambitious man with a keen interest in theology. He had a grand vision to restore the empire, which involved reuniting the East and West, putting the Roman papacy back under imperial protection, and bringing all his subjects to the one orthodox faith. After succeeding his uncle Justin in 527, he cracked down on non-Christians in the empire, shutting down the School of Athens and pagan temples like those of Baalbek and Philae. He published a Code of Laws in 528 that included a theopaschite confession of faith in its preamble. After stabilising his eastern borders in the Iberian War, he sent his general Belisarius to reconquer Africa and Italy, making the Byzantine Empire larger than it had ever been or would ever be. He also began the construction of the Hagia Sophia as a church for all his Christian subjects, and it would remain the world's largest cathedral for nearly a thousand years.[50]

In his dealings with non-Chalcedonians, Justinian was advised and helped by his Miaphysite wife Theodora.[51] In 532, following her advice, he invited 6 Chalcedonian and 6 Miaphysite theologians a conference in Constantinople. This was one of the very few times in the schism's history that competent representatives from either side calmly discussed their differences. The Miaphysites admitted that Eutyches was a heretic and that Dioscorus, while personally orthodox, made a mistake in 449 by restoring him. Meanwhile, the Chalcedonians fully accepted theopaschism.[52] When Justinian asked the non-Chalcedonians what their biggest issues with Chalcedon were, they mentioned the fact that Chalcedon had restored two Nestorian bishops to their sees: Theodoret of Cyrrhus and Ibas of Edessa. The Chalcedonian delegates admitted that Ibas' letter to Mari the Persian had doctrinal issues, but were unable to condemn him because Chalcedon had declared him orthodox. At the end of the conference, Justinian asked the non-Chalcedonians to recognise that the Chalcedonians are not heretics, but they refused. However, one of the Miaphysite delegates, Philoxenus of Doliche, converted to Chalcedonian Christianity.[53]

The conference gave Justinian the impression that further interfaith discussion could alleviate the religious division in his empire. To promote theopaschism, and thus help his Miaphysite subjects integrate into the state church, he had the hymn Only-begotten Son added to the order of the eucharistic synaxis.[54] During this time, in 535, Severus himself came to Constantinople to negotiate with its Patriarch, Anthimus, a reunion of the two churches which would have involved the Miaphysites accepting Chalcedon.

Modern dialogue

Notes

- ^ "Monophysite" is a modern, often pejorative term for non-Chalcedonians, who were known at the time as διακρινόμενοι (hesitants) or ἀποσχισταί (dissidents).[1] The Oriental Orthodox Churches prefer the term "miaphysite" to describe their Christology, partly because of the slight difference in meaning between Greek μόνος (only one) and μία (one), and partly to allude to Cyril of Alexandria's formula "μία φύσις τοῦ θεοῦ λόγου σεσαρκωμένη".[2]

- ^ In Cyril's first letter to Succensus, Bishop of Diocaesarea, he wrote "After the union has occurred, however, we do not divide the natures from one another, nor do we sever the one and indivisible into two sons, but we say that there is One Son, and as the holy Fathers have stated: One Incarnate Nature of The Word."[5] (Greek: Μετὰ μὲν τοι τὴν ἕνωσιν οὐ διαιροῦμεν τάς φύσεις , ἀλλ’ ἕνα φαμὲν Υἱόν, καὶ ὡς οἱ πατέρες εἰρήκασιν, μίαν φύσιν τοῦ Θεοῦ Λόγου σεσαρκωμένη).[6]

- ^ Jerusalem was not a patriarchate until 451.

- ^ Theodore of Mopsuestia was quoted as saying "When they ask whether Mary was Anthropotokos or Theotokos we shall answer that she was both: he who was in the womb of Mary was man, and he came forth from there. She is Theotokos because God was in the man that was born."[11] His justification for the title was criticised as "impious" in the 6th Canon of the 5th Ecumenical Council.[12]

- ^ The original Greek of Cyril's Laetentur Caeli letter to John of Antioch, which contains the Formula of Reunion, can be read here. An English translation from the NPNF can be read here.

- ^ That is the traditional number, but the acts of the counci seldom record more than 300 present at any one time.[25]

- ^ According to Michael the Syrian, the Jews supposedly sent this letter to Marcian:[35]

To the merciful Emperor Marcian: the people of the Hebrews... for a long time we have been regarded as though our fathers had crucified a God and not a man. Since the synod of Chalcedon has assembled and demonstrated that he who was crucified was a man and not a God we request that we should be pardoned this fault and that our synagogues should be returned to us.

- ^ According to Evagrius Scholasticus, Priscus of Paniou witnessed "the license of the soldiery towards the wives and daughters of the Alexandrians"[38] (Κἀντεῦθεν τῶν στρατιωτῶν παροινούντων ἔς τε τὰς γαμετὰς καὶ θυγατέρας τῶν ᾿Αλεξανδρέων).[39]

- ^ Proterius' death would later prove that their fears were well-founded.

- ^ Cyril's 12 anathema:

Leo's Tome:The Word of God suffered in the flesh

Nicene Creed:The impassible God did not disdain to be a passible man, nor the immortal one to submit to the laws of death

The only-begotten Son of God, begotten of the Father before all ages; Light of Light, true God of true God... was crucified for us under Pontius Pilate, and suffered and was buried

- ^

According to historian Richard Price, the actual intention of this sentence was to anathematise the minority of bishops at Chalcedon who were accused of Nestorianising, particularly Theodoret of Cyrrhus and Ibas of Edessa.[7]Everyone who has held or holds any other opinion [than that of Nicaea], either at the present or another time, whether at Chalcedon or at any synod whatsoever, we anathematize, and especially Nestorius and Eutyches and those who uphold their doctrines.

References

- ^ a b Frend 1972, p. xiii

- ^ Wahba, Fr Matthias (2016). "Coptic interpretations of the Fourth Ecumenical Council" (PDF). p. 5.

- ^ Kazhdan 1991, p. 404

- ^ Price & Gaddis 2007, p. 82 "The fathers of Chalcedon were profuse in their professions of loyalty to Cyril. Even when judging the Tome of Pope Leo (the great western Christological statement, formally approved at Chalcedon), their criterion of orthodoxy remained agreement with Cyril; this is clear throughout the lengthy discussion of the Tome in the fourth session."

- ^ Cyril of Alexandria 2013

- ^ Isaias, Christos (2012) [434–438]. "The notion of "enhypostaton" on St John Damascene" (PDF). p. 33.

- ^ a b c Price 2009, p. 16–17

- ^ Price 2009, p. 76, 79; Frend 1972, p. 5; Brock 1996, p. 31; Price & Gaddis 2007, p. 76

- ^ Frend 1972, p. ix–x

- ^ Price & Gaddis 2007, p. 35

- ^ a b Frend 1972, p. 14–16

- ^ "Second Council of Constantinople". Translated by Percival, Henry. 1900 [553].

- ^ a b Frend 1972, p. 18

- ^ Price 2009, p. 78

- ^ Frend 1972, p. 20

- ^ Price 2009, p. 80; Frend 1972, p. 23

- ^ Wickham 1983, p. 92 "They forgot, though, that all things regularly distinguished at the merely speculative level isolate themselves completely in mutual difference and separate individuality." (Greek: ἀλλ ἡγνόησαν, ὅτι ὅσα κατὰ μόνην τὴν θεωρίαν διαιρεῖσθαι φιλεῖ, ταῦτα οὐ πάντως καὶ εἰς ἑτερότητα τὴν ἀνὰ μέρος ὁλοτρόπως καὶ ἰδικῶς ἀποφοιτήσειεν ἂν ἀπ ἀλλήλων.)

- ^ Frend 1972, p. 29–30

- ^ a b Meyendorff 1989, p. 166

- ^ Price & Gaddis 2007, p. 42–44

- ^ Price & Gaddis 2007, p. 49–50

- ^ a b Price & Gaddis 2007, p. 54–56

- ^ Frend 1972, p. 44–45

- ^ Claremont Coptic Encyclopedia (1991). "Leo I The Great".

- ^ Price & Gaddis 2007, p. 60

- ^ Price 2009, p. 81

- ^ Price & Gaddis 2007, p. 62

- ^ a b Meyendorff 1989, p. 170–171

- ^ Price 2009, p. 56

- ^ Price & Gaddis 2007, p. 236

- ^ Frend 1972, p. 4; Price & Gaddis 2007, p. 592; Schwartz 1933, p. 131

- ^ Price & Gaddis 2007, p. 85–86

- ^ Frend 1972, p. 2

- ^ Frend 1972, p. 144–145

- ^ Frend 1972, p. 148; Syrus 1871, p. 96

- ^ a b Meyendorff 1989, p. 188

- ^ Frend 1972, p. 151; Price & Gaddis 2007, p. 69

- ^ Scholasticus 1846

- ^ Scholasticus 1844, p. 37

- ^ Meyendorff 1989, p. 189–190; Frend 1972, p. 162; Elkommos, Helmy. ثلاثون ألف شهيد ونفى البابا تيموثاوس - كتاب يا أخوتنا الكاثوليك، متى يكون اللقاء؟ (in Arabic).

- ^ Price 2009, p. 23; Meyendorff 1989, p. 219

- ^ Meyendorff 1989, p. 191, 217

- ^ Frend 1972, p. 168

- ^ Frend 1972, p. 170–173

- ^ Meyendorff 1989, p. 201–202

- ^ Meyendorff 1989, p. 204

- ^ Price 2009, p. 19–20

- ^ Frend 1972, p. 236; Price 2009, p. 21; Meyendorff 1989, p. 213

- ^ Meyendorff 1989, p. 219–220; Frend 1972, p. 245–246

- ^ Meyendorff 1989, p. 206–210, 222–223

- ^ Meyendorff 1989, p. 211

- ^ Meyendorff 1989, p. 223

- ^ Price 2009, p. 26

- ^ Meyendorff 1989, p. 224; Price 2009, p. 26

Sources

- Brock, S. P. (1996). "The 'Nestorian' Church: a lamentable misnomer" (PDF). Bulletin of the John Rylands Library. 78 (3): 23–35. doi:10.7227/bjrl.78.3.3.

- Cyril of Alexandria (2013) [434–438]. "First Letter of Cyril to Succensus". Translated by McGuckin, Fr John.

- Frend, William (1972). The Rise of the Monophysite Movement. BoD – Books on Demand. ISBN 978-0227172414.

- Kazhdan, Alexander (1991). Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Vol. I. Oxford University Press.

- Malalas, John (2019) [563]. Malalas, Chronography Bks 1-7, 10-18. Translated by Kiesling, John.

- Meyendorff, John (1989). Imperial unity and Christian divisions: The Church, AD 450–680. St. Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 978-0881410556.

- Price, Richard (2009). The Acts of the Council of Constantinople of 553 (PDF). Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-1-84631-178-9.

- Price, Richard; Gaddis, Michael (2007). The Acts of the Council of Chalcedon (PDF). Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-1-84631-100-0. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-02-11.

- Scholasticus, Evagrius (1846) [593]. Ecclesiastical History (431–594 AD), Book 2. Translated by Walford, Edward.

- Scholasticus, Evagrius (1844) [593]. Evagrii Scholastici Epiphaniensis et ex praefectis ecclesiasticae historiae (in Greek).

- Schwartz, Eduard (1933) [451]. Acta Conciliorum Oecumenicorum. Concilium Universale Chalcedonensis.

- Syrus, Michael (1871) [1195]. The Chronicle of Michael the Great, Patriarch of the Syrians (PDF). Translated by Bedrosian, Robert.

- Theophanes (1997) [815]. The Chronicle Of Theophanes Confessor, Trans. By Cyril Mango (1997). Translated by Mango, Cyril.

- Wickham, Lionel (1983). Cyril of Alexandria Select Letters. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0198268109.