Cetate, Timișoara

Cetate

| |

|---|---|

District of Timișoara | |

| |

| Coordinates: 45°45′22″N 21°13′46″E / 45.75611°N 21.22944°E | |

| Country | Romania |

| County | Timiș |

| City | Timișoara |

| Area | |

• Total | 4.8 km2 (1.9 sq mi) |

Cetate (Hungarian: Belváros; German: Innerstadt; Serbian: Град, romanized: Grad) is the central district of Timișoara, located on the site of the Vauban-style Timișoara Fortress. Traditionally, it corresponds to the first constituency (Romanian: circumscripție) out of Timișoara's ten administrative constituencies. The district underwent modernization during the Belle Époque period, particularly throughout the three decades when Carol Telbisz served as mayor of the city.

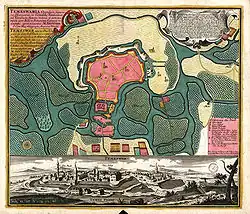

The district's name derives from the historic fortifications that Timișoara possessed over the centuries. The city once had both an old medieval fortress and a newer, more modern one—remnants of which are still visible today. The latter, significantly larger, was constructed between 1723 and 1765. Its construction, considered the most extensive project of the 18th century, cost 20 million Austrian florins. Fragments of these fortifications are still preserved in areas such as the Theresia Bastion, Piața 700, and the Botanical Park.

History

The name of the Cetate district refers to the series of fortifications that stood on this site over the centuries, evolving in form and function under different rulers. It is believed that the original fortress was constructed in the 10th century in the Avar architectural style[2] and, surrounded by defensive moats, was situated where Timișoara's National Theatre and Opera House now stand.[3]

Following the defeat of the Wallachian ruler Ahtum, the region was incorporated into the Kingdom of Hungary by its first king, Stephen I.[4] The fortress was first mentioned in 1212 under the name castrum regium Themes, in a charter issued by King Andrew II of Hungary from the Árpád dynasty.[5]

In 1241, the Mongol invasion swept in from the north, leaving the Banat region in ruins. After their retreat, Hungarian King Béla IV invited German settlers to repopulate the area and rebuild the fortress. The original earth and stone walls were reinforced with limestone and bricks, while the surrounding moats were deepened and expanded.[3]

In 1307, Charles I of Hungary ordered the construction of a new royal fortress. At that time, the Begh (now known as the Bega River, also referred to as Little Timiș) split into three branches in the area, with the central branch flowing along what is now Alba Iulia Street. The original Árpád-era fortress was located between the central and western branches. Rather than expanding the existing earthen fortification, Charles I chose to build a new stone fortress between the central and eastern branches—temporarily creating two fortresses in the area. By 1315, he had completed a royal castle on this island, which became one of the strongest defensive structures of the Middle Ages and served as his seat of government for nearly eight years. This castle would later form the foundation for what became the Hunyadi Castle. After Charles I's death in 1342, the royal castle passed into crown ownership.[4]

The fortress gradually lost its strategic importance, and following an earthquake, its walls were left to deteriorate for a time. However, with the growing threat of Ottoman expansion into Europe and the advent of gunpowder in warfare, the fortifications were later upgraded to reflect contemporary military advancements. The walls were rebuilt using sturdy oak beams, palisades were constructed, and the entire complex was encircled by two or three moats. Loopholes were added for defense, and the towers were fitted with cannons.[6]

During the reign of Sigismund of Luxembourg (1387–1437), who later became Holy Roman Emperor, the castle was restored by Pippo Spano of Ozora. At that time, the fortifications were reinforced with earthen ramparts and palisades. The fortress featured four gates: the Lippa Gate (also known as "Praiko"), the Transylvanian Gate, the Arad Gate, and the Water Tower Gate. Most of the town's buildings were constructed from wood or clay mixed with chaff. It was also during this period that the suburban areas of Little Palanka and Great Palanka began to develop, both enclosed by palisades.[7]

On 5 June 1443, a powerful earthquake struck the area, causing severe damage to the castle and fortress walls, with parts of the structures collapsing. In response, the Grand Commandant, John Hunyadi, commissioned architect Paolo Santini da Duccio to oversee the reconstruction of both the castle and the fortifications. The rebuilding process lasted from 1443 to 1447 and reflected the evolving nature of warfare influenced by the rise of gunpowder. Traditional catapults were replaced with cannons, and the heavily damaged Anjou castle was demolished. In its place, the new Hunyadi Castle was constructed, oriented perpendicular to the original layout of Charles I's castle. The new structure featured multiple bastions and was armed with cannons. It had three main gates—facing east, west, and north. Defensive towers were added to the northern and northeastern sections of the fortress walls, which were also fronted by double moats. On the southern and western sides, where the fortress met the Bega marshes, oak palisades provided protection. Of the old Anjou fortress, only the foundation stones and the water tower remained. The new fortress walls extended along what are now Mărășești Street, Eugene of Savoy Street, and Carol Telbisz Street, running southeast near the later Transylvanian Barracks and encircling Hunyadi Castle to the south.

The two suburbs, Great Palanka to the west and Little Palanka to the east, were also protected by palisades, earthworks, and moats. Stone for the fortifications was sourced from the Vršac Mountains, while sand and gravel came from Lipova, and timber was gathered from nearby forests. The labor force was made up of Vlachs and Serbs who had settled in what is now the Fabric district.

After ascending to the throne in 1490, King Vladislav II ordered the refortification of the Cetate. The project was overseen by Count Pál Kinizsi, who also contributed part of his own funds toward the effort.[8] At that time, the Cetate was regarded as one of the strongest fortresses, vulnerable only from the north and west, while the remaining sides were naturally defended by the marshes of the Bega River. The Cetate consisted of three main sections: the castle, the residential areas, and the island known as the Little Palanka to the east. Outside the fortress walls lay the Great Palanka to the west. Positioned between the castle and the residential areas was the water tower, the fortress's most critical defensive structure, through which the road connecting the castle to the residential district passed via a bridge. Hunyadi Castle itself was protected by sturdy walls and moats.

.jpg)

After the Ottoman conquest in 1552, the fortress was left in a severely damaged state, with its walls badly battered by cannon fire. Kasım Pasha promptly initiated repairs, conscripting Vlachs from nearby villages for forced labor.[9] The city's churches were transformed into mosques. At that time, the streets were not yet paved; muddy paths were mostly covered with wooden planks. Most houses were constructed from wood, while prayer houses, the Powder Tower, the mill, and some administrative buildings were built of brick in an oriental architectural style.

Around 1642–1643, the Cetate was reinforced under the direction of a captured German architect. Andrea Cornaro from Crete was tasked with renovating the fortifications and canalizing a branch of the Bega River.[10]

In 1660, the Ottoman traveler Evliya Çelebi provided a detailed description of the Cetate, stating:

Tamışvar lies in the marshes of the Tamış River, like a tortoise in water. Its four legs are the four large bastions, but the inner castle is its head. Its shape is five-cornered. There are neither bricks nor stones within it, as it is a fortress built of thick oak logs covered with woven fences. The skilled builder made this fence of wild vines and covered it with plaster and lime, creating a white castle. The walls are fifty feet thick, in some places even sixty. All around is a deep moat, and at three points there are guard rooms overlooking the moats. Every evening, nine bands play, and all the sentries call out to each other from time to time throughout the night: 'Allah akbar!' The fortress has no loopholes or defensive turrets, but it does have many gun embrasures. In total, there are 200 fine cannons. The number and quantity of the Only the Most High God knows the extent of the war equipment, as well as the fodder and provisions stored in the fortress. The fortress can be circumnavigated on the ramparts in an hour.

At that time, the fortress featured five gates, two of which—located in the south and east—were known as Azab. Additionally, there were the Rooster Gate (named after the weather vane above it) in the north, the Water Gate, and the Shore Gate.[11] The Cetate contained 1,200 houses divided into four residential districts, along with ten suburbs housing an additional 1,500 homes.[12]

After the Habsburgs recaptured the fortress in 1716, it was redesigned between 1723 and 1765 in the then-popular Vauban style. The new fortifications replaced the older, smaller Ottoman citadel and included nine bastions, of which only four smaller wall fragments remain today, aside from the Maria Theresa Bastion. This bastion, constructed of brick between 1730 and 1735, covers approximately 1.7 hectares in the current city center. These remnants can be found along Alexandru Ioan Cuza Street, within the Botanical Park, and at Timișoara 700 Square—located both north and south of Coriolan Brediceanu Street.[13] Under the direction of Governor Claude Florimond de Mercy, the Bega Canal was constructed starting in 1728, helping to drain the surrounding marshlands.[14]

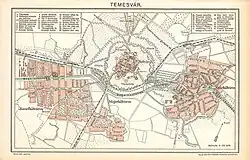

After the Hungarian Revolution of 1848/1849, the castle and its fortifications lost their strategic importance, leading to the demolition of the walls and castle gates. Starting in 1895, urban planning transformed the Cetate into the city center of what was then Temesvár. It was connected to the suburbs by wide, primary traffic routes—such as today's 1989 Revolution Boulevard—measuring 40 meters across. The city center's dense, grid-like street layout was encircled by a ring road modeled after Vienna's. By 1910, the outer districts had merged with the Cetate area, creating a continuous urban landscape. The bombings and battles during World War II caused little significant damage to the buildings in Cetate.

The Transylvanian Barracks, constructed between 1719 and 1723 and measuring 483 meters long—making it the longest building in Europe—were demolished in 1964 during the communist dictatorship. Throughout this time, many buildings in Cetate experienced neglect and poor maintenance. However, following the Romanian Revolution of 1989, new investments in renovating the often dilapidated structures have positively transformed the city's appearance.

Landmarks

Squares, buildings, statues

-

_02.jpg) Victory Square

Victory Square -

.jpg) Union Square

Union Square -

Liberty Square

Liberty Square -

Ion I. C. Brătianu Square

Ion I. C. Brătianu Square -

Hunyadi Castle

Hunyadi Castle -

_-_img_12.jpg) Piarist Complex

Piarist Complex

Parks

Expansive parks were established on the formerly undeveloped land between the fortress and the Bega River. These include, from west to east: Central Park, Cathedral Park, Roses Park, and Children's Park. Additionally, the Civic Park is located in the heart of the district, while the Botanical Park lies to the northwest.[15]

Bridges

The following bridges cross the Bega River and connect the inner city with other districts of Timișoara (from west to east):

References

- ^ Rieser, Hans-Heinrich (1992). Temeswar: geographische Beschreibung der Banater Hauptstadt. Sigmaringen: Thorbecke. p. 101. ISBN 3-7995-2501-7.

- ^ Zollner, Anton. "Aus der Vorgeschichte der Temeschburger Festung". Banater Aktualität.

- ^ a b Zollner, Anton. "Die Temeschburger Festung unter den Árpáden". Banater Aktualität.

- ^ a b Berkeszi, István (1900). Temesvár szabad királyi város kis monographiája (PDF). Timișoara: Henrik Uhrmann.

- ^ Giurescu, Constantin C.; Giurescu, Dinu C. (1974). Istoria românilor. Vol. 1. Din cele mai vechi timpuri până la întemeierea statelor românești. Editura Științifică. p. 241.

- ^ Zollner, Anton. "Temeschburg - die Hauptstadt Ungarns". Banater Aktualität.

- ^ Zollner, Anton. "Die Temeschburger Festung unter dem Hause Luxemburgern". Banater Aktualität.

- ^ Zollner, Anton. "Die Temeschburger Festung unter den Corvins". Banater Aktualität.

- ^ Kul, Eyüp (2019). "Temeşvar Eyaleti'ne nizam verme çalışmaları ve Temeşvar'ın kaybı öncesinde yapılan faaliyetler (1700-1715)" (PDF). International Journal of History. 11 (3): 1009–1029. doi:10.9737/hist.2019.751. ISSN 1309-4173.

- ^ Ottendorf, Henrik (2006). De la Viena la Timișoara. Timișoara: Banatul. ISBN 973-97121-7-7.

- ^ Iliuță, Silviu (2022). "Ottoman fortifications on the territory of Banat (the 16th–18th centuries)". Ziridava. Studia Archaeologica. 36 (1): 259–315. ISSN 2392-8786.

- ^ Zollner, Anton. "Temeschburg während der Türkenherrschaft". Banater Aktualität.

- ^ Opriș, Mihai (2007). Timișoara. Monografie urbanistică. Vol. 1. BrumaR. ISBN 978-973-602-245-6.

- ^ Magina, Adrian (2015). "From swamp to blessed land: transforming medieval landscape in the Banat" (PDF). Banatica. 25: 115–121.

- ^ Ciupa, Vasile (coord.) (2010). Cadrul natural și peisagistic al municipiului Timișoara (PDF). Vol. I. Cadrul natural. Timișoara. p. 17.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)