Calendars of Laurynas Ivinskis

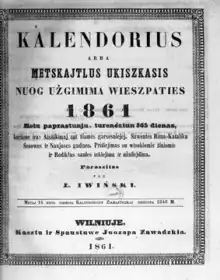

Farmer's Calendar or Year Counter (Lithuanian: Kalendorius, arba Metskajtlus ukiszkasis) were annual Lithuanian-language calendars or almanacs compiled by Laurynas Ivinskis. These calendars were the first periodical Lithuanian publication in the Russian Empire.[1] 21 issues of the calendar were published in the Russian Empire from 1846 to 1867 with an additional issue in 1878; three of them were published in the Cyrillic script due to the press ban. Due to the ban, at least five calendars were published in East Prussia from where it was smuggled into Russia.

The calendars ranged from 32 to 64 pages in length and included astronomical information, lists of religious feasts, articles on agriculture, medicine, veterinary science, and housekeeping. The calendars are valued for including a literary section which published examples of Lithuanian folklore, didactic stories, and original and translated poems. In 1860–1861, the calendars were first to publish the epic poem The Forest of Anykščiai by Antanas Baranauskas which has become a classic work of Lithuanian literature. Other notable published authors included Silvestras Valiūnas, Dionizas Poška, Karolina Proniewska, Antanas Strazdas, and Jurgis Pabrėža.

Publication history

Number of issues

It is likely that Ivinskis was inspired to publish a Lithuanian calendar after he bought the popular Polish calendar Kalendarz gospodarski (Farmer's Calendar) in 1842.[2] Ivinskis prepared his first calendar for publication in fall 1845.[3] The first issue of Ivinskis' calendar was published for year 1846 and became the first Lithuanian calendar. Erdmonas Šesnakas published a calendar for Prussian Lithuanians in East Prussia for year 1847.[4]

Due to the Russian censorship, Ivinskis' calendars for 1853 and 1854 were not published.[5] Censor Antanas Petkevičius (graduate of Varniai Priest Seminary who converted to Eastern Orthodoxy) was a demanding reviewer.[6] He paid particular attention to the list of historical events and objected to the use of the word "Muscovy" to refer to Russia. He also objected that Tsar was referred to as king and not emperor.[6] Due to the delays in censorship and financial difficulties, the calendars for 1853 and 1854 were not published but their content was reused for later issues.[7]

The 1865–1867 calendars were printed in the Cyrillic due to the Lithuanian press ban.[5] The 1865–1867 calendars were sponsored by a government commission tasked with the implementation of the Cyrillic in Lithuanian publications. Jonas Krečinskis assisted in compiling the 1866–1867 calendars and took over the publication of the calendars after Ivinskis resigned from the commission in spring 1866.[8] The 1867 calendar was renamed to Russian–Lithuanian Calendar and promoted the Eastern Orthodox Church causing a conflict with bishop Motiejus Valančius who usually reviewed and approved Ivinskis' calendars for publication.[9] Such calendars continued to be published until 1872. These calendars were not popular and their printing runs steadily decreased from 3,500 copies in 1868 to 900 copies in 1871.[8]

With the help of Ireneusz Kleofas Ogiński,[10] Ivinskis attempted to get permissions to publish his calendar for 1872 and a prayer book in Lithuanian.[11] The calendar was printed but then confiscated; Ivinskis demanded 3,000 rubles from the authorities to compensate for his losses.[10] Ivinskis and other Lithuanian activists managed to get permissions to publish the 1878 calendar in Latin alphabet in Saint Petersburg.[12] 1,200 copies of this calendar were printed.[13] Further efforts of publishing the calendar in Russia were rejected, including 1879 and 1880 calendars.[14] Therefore, in total, Ivinskis published 21 issues of his calendar in Russia (1846–1852, 1855–1867, 1878).[15]

Due to the ban, Ivinskis published at least five calendars (1870, 1874, 1876, 1877, 1879) in Tilsit, East Prussia, from where it was smuggled into Russia.[16] Because these calendars were illegal, they were unsigned and it is difficult to ascertain their authorship. It is likely that Ivinskis was at least partially involved in publishing other calendars in East Prussia, particularly for 1869 and 1873.[16]

Finances

Until 1867, the calendar was printed by the Zawadzki printing shop in Vilnius. Until 1855, Ivinskis financed the publication from his personal funds.[17] His annual salary was 120 to 150 Russian rubles; the annual publishing costs were about 180 rubles. Therefore, Ivinskis had to borrow money, often from the Ogiński family.[17] He borrowed 60 Russian rubles from Ireneusz Kleofas Ogiński, the owner of the Rietavas Manor, for the publication of his first calendar.[18]

The calendars were sold for 10 to 20 kopecks (most other calendars cost 30–40 kopecks).[19] Ivinskis received 400–500 copies of the calendar so he could recoup printing costs by selling them, but he was not very successful at it.[20] In total, Ivinskis lost about 1,000 rubles publishing the calendars. When the calendars became more popular, Zawadzki printing shop agreed to finance the publication.[21]

The calendars were sold mainly in Samogitia. Ivinskis tried to have the calendars printed by early September so that they could be sold during the parish feast in Šiluva.[20] Ivinskis sent copies of the calendars to various Lithuanian nobles. Ireneusz Kleofas Ogiński usually received about 100 copies. Varniai Priest Seminary distributed about 2,000 copies of the calendars per year.[20] The main distributor of the calendars was the bookshop of the Zawadzki printing shop in Varniai. In ten years, it received about 35,000 copies of the calendar for sale.[22]

Number of copies

It is believed that 1,500 copies of the first 1846 calendar were printed.[23] The run increased to 3,400 copies for the 1852 calendar.[21] For the 1855 calendar, the plans were to include a map of Telšiai powiat and increase the run to 10,000 copies.[19] The map, measuring an arshin (71.12 centimetres or 28.00 inches), was prepared and engraved by Ivinskis. It would have been the first published map in the Lithuanian language, but it was not published and the number of copies was decreased.[24]

The 1861 calendar was published twice. The first run of 8,000 copies was quickly sold out; it included the poem The Forest of Anykščiai by Antanas Baranauskas. This prompted the second run of 3,000 copies, but to expedite the printing the length of the calendar was reduced from 64 to 40 pages, eliminating the poem. This run remained unsold.[19]

Content

Structure

The calendars ranged from 32 to 64 pages in length.[25] They were aimed at Lithuanian peasants. Their content was original and not borrowed from similar Polish or Russian calendars.[17] The calendars included astronomical information (Zodiac signs, information on planets in the Solar System), lists of religious feasts and important historical events, including from the history of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.[26] The days and months were printed in Lithuanian, Latin, and Polish using both the Julian ("old style" still used in Russia) and Gregorian calendars.[17]

The calendar was then followed by supplements which included articles on agriculture, medicine, veterinary science, housekeeping, proper behavior and etiquette.[27] From 1849 to 1855, the calendars included a religious section.[26] In 1849, Ivinskis published the first literary work (translation of poem A Poem on the Last Day by Edward Young). In 1851, the literary section became a firmly established part of the calendar.[26] The calendar ended with a list of fairs and markets held in various Lithuanian towns, table of sunsets and sunrises, and weather and harvest predictions.[17]

Occasionally, the calendars included articles on other matters. For example, an article on the history of Kaunas was published in 1860.[17] The same year, Ivinskis published a bibliography of Lithuanian books – he added 47 entries to the first bibliography published by Kajetonas Nezabitauskis in 1824.[28] In 1861–1863, calendars published a list of Lithuanian books advertising them to the potential readers.[29]

Medical advice

In almost every calendar, Ivinskis published articles on advice how to treat ailments and diseases, ranging from minor (e.g. warts, sprain) to major (e.g. dysentery, cancer) conditions.[30] He used various published and folk treatments, and most frequently prescribed herbal remedies.[31] Ivinskis prepared a separate book on human and animal treatments, but it remained unpublished.[32] Most of his remedies are questionable if not outright ridiculous by modern standards, but it reflected the level of medical science in the 19th century in general and lack of medical care in Lithuania in particular.[33]

Astronomical information

The calendars contained astronomical information, mainly about the Sun and planets in the Solar System, solar and lunar eclipses, comets (including 1858 Comet Donati that Ivinskis witnessed personally), lunar phases, times of sunrises and sunsets.[34] Ivinskis focused on scientific information, including new discoveries, and not on horoscope or predictions as in many other calendars.[35] For specific local information, he obtained astrological information from the Vilnius University Astronomical Observatory.[36] Since Ivinskis was one of the first to write about astronomy in Lithuanian, he had to create or find numerous Lithuanian words for astrological terms.[37]

Lithuanian folklore

In the calendars, Ivinskis published different genres of Lithuanian folklore, including fairytales, songs, proverbs, and riddles.[38]

The calendars published seven Lithuanian fairytales.[39] Ivinskis also published a myth about Praamžius, the chief deity in the Lithuanian mythology, which he translated from the history of Lithuania by Teodor Narbutt.[40] In the 1846 calendar, he also published a list of Lithuanian gods and mythological figures based on works by Narbutt and Jan Łasicki.[41]

Ivinskis collected Lithuanian folk songs, but published only nine of them in the calendars.[42] They included three humorous, two social-historical, one youth, two wedding, and one celebration songs.[43] While Ivinskis collected the songs from the people and did not borrow them from published works, he chose to publish popular songs and some of them were already included in other song collections published by Simonas Daukantas, Simonas Stanevičius, and Ludwig Rhesa. Therefore, only three songs were not yet published by others.[44]

Ivinskis collected Lithuanian proverbs and riddles as they helped him compile a Lithuanian dictionary (unpublished).[45] He rewrote many of the probers as couplets. In total, the calendars included 355 proverbs, 243 of which were in the form of a couplet, and 21 riddles.[46]

Fiction

The calendars included 15 longer and six short didactic stories or sketches. These were texts promoting moral values and Christian virtues.[47] Some of these texts were quite simple and barely qualify as a work of fiction. Other texts were written based on motifs and plot devices borrowed from folklore or translated from other publications (three stories were translated from works by Ignacy Krasicki).[48] Researchers attribute authorship of at least five stories to Ivinskis.[49] In addition to didactic stories, Ivinskis published two stories and one article by Juozapas Silvestras Dovydaitis; they all concerned the temperance movement which was promoted by bishop Motiejus Valančius.[50]

The fiction section was closely monitored by the Russian censors. They objected to any references to social inequality and criticism of the ruling classes, even in abstract allegorical stories about a conceited ruler.[51]

Poetry

Ivinskis published several poems in the calendars. He referred to them as song and did not indicate authors (occasionally, he indicated initials or pen name of the author).[52]

In 1851–1852, the calendars published two poems by Silvestras Valiūnas.[52] Poem Rašančiam lietuvišką žodįnį (To Those Writing the Lithuanian Word) is addressed to Dionizas Poška, praises his work on the Lithuanian language, discusses the issues of language purity, and the need for standardized Lithuanian.[53] Poem Birutė is Valiūnas most popular work which became a folk song.[54] It is about the Grand Duchess Birutė and was adapted into the first Lithuanian opera Birutė in 1906.[55] Ivinskis wanted to publish two different sheet music to Birutė, but it was not accomplished.[56]

In 1859, Ivinskis published rhymed fairy tale Žalčio motė (based on Eglė the Queen of Serpents) translated from Polish by Karolina Proniewska. It was a rather free translation from Anafielas by Józef Ignacy Kraszewski.[57] It became the first published Lithuanian poem by a woman.[58]

In 1860–1861, Ivinskis published epic poem The Forest of Anykščiai by Antanas Baranauskas. The poem was published just months after it was completed by then 23-year old Baranauskas. Thus, Ivinskis discovered Baranauskas.[58] The publication was flawed (about 20 out of 342 lines were missing, there were proofreading errors, Ivinskis edited the poem to make it more suitable to people speaking the Samogitian dialect), but it was the most widely accessible edition and contributed to poem's popularity.[59] In 1861 and 1863, Ivinskis published three other poems by Baranauskas – a 800-line original poem, a translation from Polish, and an original poem of low artistic value. All three poems promoted the temperance movement.[60]

In 1861, the calendars included humorous poem Kiškis (Hare) by Antanas Strazdas. It was copied from a collection of poems published in 1814.[61] The same calendar published poem Artojas (Ploughman) by Jurgis Pabrėža. It was the first and most authentic publication of the poem which deals with economic hardship and oppression faced by Lithuanian farmers.[62]

In 1863, Ivinskis published Mano darželis (My Garden) and Gromata pas Tadeušą Čackį (Letter to Tadeušas Časkis), two poems by Dionizas Poška.[61] These autobiographical poems provide insight into the daily life of Poška and the early stages of the Lithuanian National Revival.[63] Additionally, Ivinskis published at least ten couplets by Poška in 1852. Ivinskis was interested in Poška's works and collected his manuscripts. Several works by Poška are known only from the archives of Ivinskis.[64]

Ivinskis published his own didactic poetry in the calendars. He is attributed two poems, two rhymed fairytales, and two rhymed fables. However, he was not a strong poet.[65] Smetona (Sour Cream), a light humorous poem about a servant who is caught snacking on sour cream, is artistically the strongest work among these. It was popular among the people and was turned into a song. It was first attributed to Ivinskis by Jonas Šliūpas, but there are serious doubts if this attribution is correct.[66]

Ivinskis also published poems by lesser known authors. These were a poem by Mikalojus Gadliauskas (1862) about tasks of a Lithuanian peasant during all four seasons, a poem by Jokūbas Kurmavičius (1860) promoting the temperance movement, a satirical poem by Karolis Bruno Rimavičius (1858) which poked fun at people's character flaws, a pastoral poem by Motiejus Žutautas (1860).[67] Authors of three other poems remain unknown.[68]

References

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 230.

- ^ Biržiška 1990, p. 121.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 121.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 119.

- ^ a b Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 126–127.

- ^ a b Labanauskienė 1997, p. 103.

- ^ Labanauskienė 1997, pp. 102, 104, 106.

- ^ a b Merkys 1994, p. 92.

- ^ Merkys 1994, pp. 55, 92.

- ^ a b Merkys 1994, p. 128.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 92–93, 95.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 127.

- ^ Biržiška 1990, p. 188.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 128, 131–132.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 131.

- ^ a b Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 129.

- ^ a b c d e f Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 123.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 30–31.

- ^ a b c Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 125.

- ^ a b c Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 126.

- ^ a b Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 124.

- ^ Ulpis 1969, p. 129.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 35–36, 125.

- ^ Biržiška 1990, p. 184.

- ^ a b c Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 122.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 123, 191.

- ^ Žukas 1983, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Žukas 1983, p. 41.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 132, 133.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 133, 135.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 138–139.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 132, 136, 138.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 139–140, 146.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 140, 142.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 148–149.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 140–141.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 150.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 151.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 153.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 154.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 155.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 156.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 156–157.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 157.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 158.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 161.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 161–163.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 188.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 168.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 170.

- ^ a b Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 171.

- ^ Lebedys 1972, pp. 298–299.

- ^ Lebedys 1972, p. 299.

- ^ Landsbergis 1976.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 172–173.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 173.

- ^ a b Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 174.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 174–175.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 175.

- ^ a b Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 176.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 178.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 176–177.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 177.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 195–196.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 197–199.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, pp. 179–184.

- ^ Petkevičiūtė 1988, p. 185.

Bibliography

- Biržiška, Vaclovas (1990) [1965]. Aleksandrynas: senųjų lietuvių rašytojų, rašiusių prieš 1865 m., biografijos, bibliografijos ir biobibliografijos (in Lithuanian). Vol. III. Vilnius: Sietynas. OCLC 28707188.

- Labanauskienė, Danutė (1997). "Neišleisti 1853-1854 m. Lauryno Ivinskio kalendoriai". Knygotyra (in Lithuanian). 33. doi:10.15388/Knygotyra.1997.14. ISSN 2345-0053.

- Landsbergis, Vytautas (1976). "Apie "Birutę"". In Burokaitė, Jūratė (ed.). Mikas Petrauskas: straipsniai, laiškai, amžininkų atsiminimai (in Lithuanian). Vaga. OCLC 3627920. adapted and cited in "Apie M. Petrausko operą "Birutė"". Aruodai (in Lithuanian). Lietuvių literatūros ir tautosakos institutas, Lietuvių kalbos institutas, Lietuvos istorijos institutas. 2003–2006. Retrieved 26 December 2022.

- Lebedys, Jurgis (1972). Lituanistikos baruose (in Lithuanian). Vol. 1. Vilnius: Vaga. OCLC 1049923.

- Merkys, Vytautas (1994). Knygnešių laikai 1864–1904 (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Valstybinis leidybos centras. ISBN 9986-09-018-0.

- Navickienė, Aušra (1993). "Juozapo Zavadzkio firmos lietuviškų leidinių platinimas 1805–1864 m." Knygotyra (in Lithuanian). 20 (27): 34–44. ISSN 0204-2061.

- Petkevičiūtė, Danutė (1988). Laurynas Ivinskis (in Lithuanian). Mokslas. ISBN 5-420-00104-7.

- Ulpis, Antanas; et al., eds. (1969). Lietuvos TSR bibliografija. Serija A: Knygos lietuvių kalba (in Lithuanian). Vol. 1 (1547–1861). Mintis. OCLC 1424644.

- Žukas, Vladas (1983). Lietuvių bibliografijos istorija (in Lithuanian). Vol. 1 (iki 1940). Mokslas. OCLC 11187042.