Burmese people in Japan

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 134,574 (In December, 2024)[1][2] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Tokyo (Shinjuku), Gunma (Tatebayashi), Nagoya | |

| Languages | |

| Japanese, Burmese | |

| Religion | |

| Buddhism · Shinto · Christianity (minority) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Burmese diaspora, Thais in Japan |

Burmese people in Japan (Japanese: 在日ミャンマー人) forms one of the significant foreigner population in Japan. In December 2024, there were 134,574 Burmese living in Japan.[3][4]

Migration history

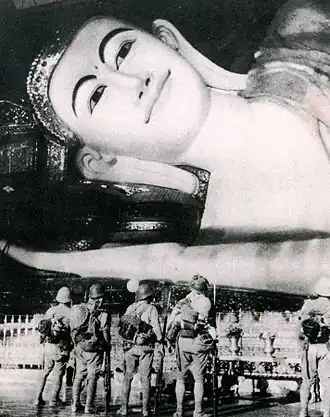

Prior to World War II, some Burmese students studied in Japan; these nationalist-oriented students became the core of the Burmese Independence Army set up by the Japanese prior to their invasion of Burma.[5] During the Japanese occupation of Burma, Japan continued to provide scholarships for Burmese students to study in Japan.[6]

Since the 1990s, a new wave of Burmese migrants have come to Japan. Among their numbers are hundreds of activists who had been active in Burmese democracy movements. Initially, the Japanese government refused to recognize any of them as refugees; however, their policy softened after 1998. By August 2006, the government had recognized 116 Burmese in Japan as refugees, and given special stay permission to another 139. These comprised almost all of the official refugees in Japan, with the exception of a few Afghans and Kurds.[7] In August 2010, the Japanese government agreed to accept for resettlement in Japan five families of Karen refugees from Myanmar, numbering 27 people; an additional family of five people chose to decline resettlement in Japan due to the country's high cost of living. The refugees had formerly been living at the Mera refugee camp in Thailand, and had been taking resettlement classes held by the International Organization for Migration.[8]

Takadanobaba in Tokyo is sometimes nicknamed “Little Yangon” which is home to numerous Burmese restaurants, grocery stores, shops, and community organizations serving both the Burmese diaspora and local Japanese citizens.[9][10]

Mingalaba, opened in 1997, is the oldest Burmese restaurant in the area.[9] Local shops such as Mother House cater largely to Burmese residents, offering regional ingredients and clothing. Burmese women often help explain traditional products to visitors.[9]

Community organisations

The first Burmese political organisation founded in Japan was the Burma Association in Japan, established in 1988.[7] In 2000, a number of Burmese dissident groups in Japan, including the Burmese Association in Japan, the Burma Youth Volunteer Association, the Students Organization for Liberation of Burma, merged to form a single organisation, the League for Democracy in Burma.[11]

Due to the Japanese government's limited assistance to refugees, Japanese voluntary civil society organisations have played a large role in providing aid to Burmese migrants, especially in the field of health care.[12] Organisations established by Burmese migrants or providing aid to them include the People's Forum on Burma, the Lawyers Group for Burmese Refugees in Japan, and the Federation of Workers' Union of Burmese Citizens in Japan.[13][14][15] Burmese associations have a strong base of support among mainstream Japanese; the umbrella organisation Burma Office in Japan is especially close to RENGO (the Japanese Confederation of Trade Unions), which provides them with financial support.[16]

Burmese in Japan are also organised in non-political associations and activities. Ahhara, the first Burmese library in Japan, was established in Itabashi, Tokyo in 2000, with the aim of collecting hard-to-obtain books and historical writings. Its name means "Food for Thought" in Burmese. In 2004, the library was moved to Shinjuku to be more conveniently accessible to the Burmese community; its name was also changed to Moe Thauk Kye, which means "Morning Star".[17] The library is staffed by 14 volunteers.[18] Burmese living in Tokyo organise a Thingyan (Burmese New Year Water Festival) celebration, which draws about 5,000 participants annually.[16]

Rakhine people in Japan are organized under groups like Arakan Union-Japan, Arakan Social Association of Japan, and Arakan National Democratic Party – Japan.[19][20] Events such as the Rakhine Thingyan Festival and the annual Fall of the Arakan Kingdom commemoration are held.[21][22] The groups actively protest in Tokyo, lobby Japanese NGOs and government officials, and align with the Arakan Army (AA).[23][24][25]

There are about 250 Rohingya refugees in Tatebayashi, Gunma.[26]

Burmese Chin community numbers hundreds across prefectures like Tokyo, Chiba, and Nagoya.[27] Several Chin-led or Chin-affiliated groups, such as the Chin Community of Japan (CCJ) and the Chin Youth Organization of Japan (CYO‑JP) are active in Japan.[28][29]

The World Peace Pagoda in Moji, Kitakyushu, is a Myanmar-style Buddhist pagoda built in 1958 to honor war victims in the World War and promote peace between Japan and Myanmar. It houses Theravada Buddhist relics and is maintained with the involvement of Burmese monks. The pagoda overlooks the Kanmon Strait and is open to visitors for cultural and religious activities.[30][31]

Burmese-Japanese co-produced films have appeared occasionally since the 1930s.[32] Early collaborations include the 1935 film Japan Yin Thwe,[33] while more recent examples are the 2003 drama Thway and the 2020 musical drama Gandaba: Strings of a Broken Harp.

Notable people

- Amisa Miyazaki, singer (half-Burmese)

- Asuka Saitō, actress (half-Burmese)

- Ten Miyagi, footballer (half-Burmese)

- Win Morisaki, singer

- U Kyaw Din, Football coach and one of Japanese football team Hall of Fame

- Ten Miyagi, footballer (half-Burmese)

Notes

- ^ "【在留外国人統計(旧登録外国人統計)統計表】 | 出入国在留管理庁".

- ^ 令和6年末現在における在留外国人数について

- ^ "【在留外国人統計(旧登録外国人統計)統計表】 | 出入国在留管理庁".

- ^ 令和6年末現在における在留外国人数について

- ^ Nemoto 2007, p. 98

- ^ Nemoto 2007, p. 101

- ^ a b Nemoto 2007, p. 106

- ^ Miyajima, Kanako (2010-08-28), "Karen refugees from Myanmar prepare for new life in Japan", Asahi Shimbun, retrieved 2010-08-30

- ^ a b c "The World Comes Together in Japan | January 2016 | Highlighting Japan". www.gov-online.go.jp. Retrieved 2025-07-24.

- ^ "Tokyo's "Little Yangon" a legacy of culture, freedom and hope". akihabara.tokyo. Retrieved 2025-07-24.

- ^ "Four Burmese dissident groups in Japan merge", Kyodo News, 2000-08-14, retrieved 2010-05-18

- ^ Banki 2006, p. 328

- ^ "Myanmar Dying to Get Out of Japan", Japan Times, 2003-09-12

- ^ Kamiya, Setsuko (2009-06-19), "Refugee treatment under spotlight: Asia-Pacific region watching how Japan handles new program for people fleeing Myanmar", Japan Times, retrieved 2010-05-18

- ^ "Gov't loses appeal to seek deportation of Myanmar asylum seeker", Kyodo News, 2006-03-13, retrieved 2010-05-18

- ^ a b Nemoto 2007, p. 107

- ^ Soe Win Shein 2006, p. 2

- ^ Soe Win Shein 2006, p. 3

- ^ "Japan-based 10 ethnic organizations denounce 195 groups' statement terming biased". Narinjara News. Retrieved 2025-07-24.

- ^ "Arakanese, their ethnic allies demonstrate in front of Tokyo's Myanmar embassy". Burma News International. Retrieved 2025-07-24.

- ^ "Fall of Arakan Kingdom observed by Arakanese organizations in Japan and South Korea". Narinjara News. Retrieved 2025-07-24.

- ^ "Arakanese traditional Thingyan Festival to be held in Japan". Narinjara News. Retrieved 2025-07-24.

- ^ "Protest in front of Tokyo Foreign Ministry draws Japanese attention to Rakhine". Narinjara News. Retrieved 2025-07-24.

- ^ "Japanese Government Representative Yohei Sasakawa Achieves Humanitarian Cease-Fire Between Myanmar Military and Arakan Army". The Nippon Foundation. 2022-11-29. Retrieved 2025-07-24.

- ^ "Myanmar nationals in Japan call for release of political prisoners". Burma News International. Retrieved 2025-07-24.

- ^ "獨協大学". Archived from the original on 2018-04-14. Retrieved 2018-04-14.

- ^ "Burma in Diaspora: A Preliminary Research Note on the Politics of Burmese Diasporic Communities in Asia | Renaud Egreteau". ResearchGate. Archived from the original on 2019-07-13. Retrieved 2025-07-24.

- ^ "မြန်မာစစ်အုပ်စု အသုံးပြုခွင့်ရရှိနေသည့်, ငွေကြေးများ၊ လက်နက်များနှင့် လေယာဉ်ဆီများကို တားဆီပိတ်ဆို့ရန် မြန်မာ ပြည်သူလူထုနှင့် ပြည်တွင်း ပြည်ပ အဖွဲ့အစည်းများမှ တောင်းဆိုသည့် စင်ကာပူအစိုးရသို့ ပေးပို့သော အိတ်ဖွင့်ပေးစာ – Progressive Voice". progressivevoicemyanmar.org. Retrieved 2025-07-24.

- ^ "Ethnic nationals protest in front of Myanmar Embassy in Tokyo". Burma News International. Retrieved 2025-07-24.

- ^ "ဂျပန်နိုင်ငံ၊ ခိတကျူးရှုးမြို့၊ မိုးဂျိကမ္ဘာအေးစေတီတော် | Embassy of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar Tokyo". Retrieved 2025-07-24.

- ^ "World Peace Pagoda | Search Details". Japan Tourism Agency,Japan Tourism Agency. Retrieved 2025-07-24.

- ^ Ferguson, Jane M. (2018). "Flight school for the spirit of Myanmar: Aerial nationalism and Burmese-Japanese cinematic collaboration in the 1930s". South East Asia Research. 26 (3): 268–282. doi:10.1177/0967828X18793046. ISSN 0967-828X.

- ^ Ferguson, Jane M (2018-09-01). "Flight school for the spirit of Myanmar: Aerial nationalism and Burmese-Japanese cinematic collaboration in the 1930s". South East Asia Research. 26 (3): 268–282. doi:10.1177/0967828X18793046. ISSN 0967-828X.

Sources

- Banki, Susan (2006), "Burmese Refugees in Tokyo: Livelihoods in the Urban Environment", Journal of Refugee Studies, 19 (3): 328–344, doi:10.1093/jrs/fel015

- Soe Win Shein (June 2006), "'Moe Thauk Kye', the First Burmese Library in Japan" (PDF), Library Services to Multicultural Populations, World Library and Information Congress, retrieved 2010-05-18

- Nemoto, Kei (2007), "Between Democracy and Economic Development: Japan's Policy towards Burma/Myanmar Then and Now", in Narayanan Ganesan; Kyaw Yin Hlaing (eds.), Myanmar: state, society, and ethnicity, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Hiroshima City University, ISBN 978-981-230-434-6

- JFA Hall of Fame Inductee|Japan Football Hall of Fame|JFA|Japan Football Association

Further reading

- Kingston, Keff (May 2008), "Political Refugees and Asylum Seekers in Japan", Paper presented at the annual meeting of The Law and Society Association, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, retrieved 2010-05-18

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link); a conference paper based on a series of interviews with Burmese asylum-seekers in Japan - ミャミャウィン (1997), カンチャマ「運命」—在日ビルマ人難民認定の3000日, ダイヤモンド社, ISBN 978-4-478-94135-5

- 原 千亜 (2008), 在日ミャンマー人の接触場面における社会文化管理-言語の社会化の事例- [Socio-cultural management in contact situations among Myanmar people in Japan: A case study of language socialization] (PDF) (M.A. thesis), Obirin University, retrieved 2009-06-09

- 田辺 寿夫 (2008), 負けるな!在日ビルマ(ミャンマー)人 [Don't give up! Burmese (Myanmar) people in Japan], 梨の木舎, ISBN 978-4-8166-0806-3