Anglo-Indian cuisine

| British cuisine |

|---|

|

| National cuisines |

| Regional cuisines |

| Overseas/Fusion cuisine |

| People |

|

|

|

Anglo-Indian cuisine is the cuisine that developed during British rule in India, between 1612 and 1947, and has survived into the 21st century. Spiced dishes such as curry, condiments including chutney, and a selection of plainer dishes such as kedgeree, mulligatawny and pish pash were introduced to British palates. Anglo-Indian food arrived in Britain by 1758, with a recipe for "a Currey the Indian Way" in Hannah Glasse's The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy.

Anglo-Indian cuisine was documented in detail by the English colonel Arthur Robert Kenney-Herbert, writing as "Wyvern" in 1885. Many of its usages are described in the 1886 Anglo-Indian dictionary, Hobson-Jobson. Definitions vary somewhat; this article follows The Oxford Companion to Food in distinguishing colonial era Anglo-Indian cuisine from post-war British cuisine influenced by the style of dishes served in Indian restaurants.[1]

History

During the British rule in India, between 1612 and 1947,[1] cooks began adapting Indian dishes for British palates and creating Anglo-Indian cuisine, with dishes such as kedgeree (by 1790)[2] and mulligatawny soup.[3] As Anglo-Indian cuisine grew in popularity in Britain, the desire for authentic Indian delicacies grew.[4] The first Indian restaurant in England, the Hindoostane Coffee House,[5] opened in London around 1810,[6] offering Indian ambience and curries as well as a hookah-smoking room.[4] As described in The Epicure's Almanack in 1815, "All the dishes were dressed with curry powder, rice, Cayenne, and the best spices of Arabia".[7] The founder, Sake Dean Mohomed, stated that the ingredients for the curries as well as the herbs for smoking were authentically Indian.[4]

The British East India Company arrived in India in 1600,[8] developing into a large and established organisation.[9] By 1760, men were returning home from India with money and a taste for Indian food.[10] In 1784, a listing in the Morning Herald and Daily Advertiser promoted ready-mix curry powder to be used in Indian-style dishes.[11] The Anglo-Indian term "curry" is derived from the Tamil word "kari" meaning a spiced sauce poured over rice, to denote any spicy Indian dish in a thick sauce.[11]

Many handwritten cookbooks including Indian-style dishes were created by British women in the late 18th century.[13] Hannah Glasse's 1758 book The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy included the recipe "To make a Currey the Indian Way".[14] Clarissa Dickson-Wright commented that the spices in the recipe did not resemble those of a modern curry, but the dish had a good flavour.[15]

Anglo-Indian cuisine was documented in practical detail by the English colonel Arthur Robert Kenney-Herbert, writing his Culinary Jottings for Madras as "Wyvern" in 1885.[1][16] Many of its usages are described in what Alan Davidson calls the "wonderful"[1] 1886 Anglo-Indian dictionary, Hobson-Jobson.[1] The Veeraswamy restaurant opened in London (in Regent Street) in 1926;[17][18] it originally served Anglo-Indian food, but as regional Indian food became popular in Britain it switched to serving dishes from Punjab and other regions.[19]

More recently, the cuisine has been analysed by Jennifer Brennan in 1990 and David Burton in 1993.[1][20][21][22] A minority mixed race Anglo-Indian community and its cuisine have survived in India into the 21st century, though the cuisine may be in decline as younger people are no longer learning the recipes.[23]

Dishes

Among colonial era Anglo-Indian creations are kedgeree, a range of curries, and mulligatawny curry soup, eaten with Indian accompaniments such as Bombay duck, chutneys, pickles, and poppadoms.[12] They freely drew on British, Dutch, French, and Portuguese cuisines as well as Indian recipes.[24]

Anglo-Indians in independent India cook a range of dishes from their traditional cuisine, including pork dishes such as pork chops, pork bhoonie, and the Goan pork assado.[25] They adopted the British custom of adding side dishes to a dinner; these could include recipes like coq au vin, roast duck with orange sauce, and pepper steak.[26] They welcome friends with tea, which may be served with British accompaniments like sandwiches, buns, and cake, and with Indian snacks like pakoras and samosas.[27] The spices they use are the same as those used in Indian cuisine.[28]

Soups

Mulligatawny soup was based on molo tunny, a watery broth of tamarind with chillies or black pepper. To this was added a small amount of vegetables, rice, and meat. It became extremely popular, representing a British idea of soup combined with an Indian recipe. It was supposedly created in Madras, but became ubiquitous across British India.[29]

Main dishes

Kedgeree derived from the simple Indian rice and lentil dish khichari. The Anglo-Indian version added garnishes of hard-boiled egg, fish, and fried onions; the British version used smoked haddock as the fish, and dropped the lentils.[30]

Anglo-Indian curries derived from Indian dishes by a process of change and simplification to meet their taste. Korma or quorema, for example, was adapted from the quarama of Lucknow by leaving out the cream and reducing the amounts of ghee, spices, and yoghurt; these were replaced by the usual Anglo-Indian spice mix of pepper, coriander, and ginger.[31]

Pish pash was defined by Hobson-Jobson as "a slop of rice-soup with small pieces of meat in it, much used in the Anglo-Indian nursery".[1] The term was first recorded by Augustus Prinsep in the mid 19th century.[32] The name may derive from the Persian pash-pash, from pashidan, to break.[1] A version of the dish, using rabbit meat, is given in The Cookery Book of Lady Clark of Tillypronie of 1909.[33]

Spices for curries in India and Britain

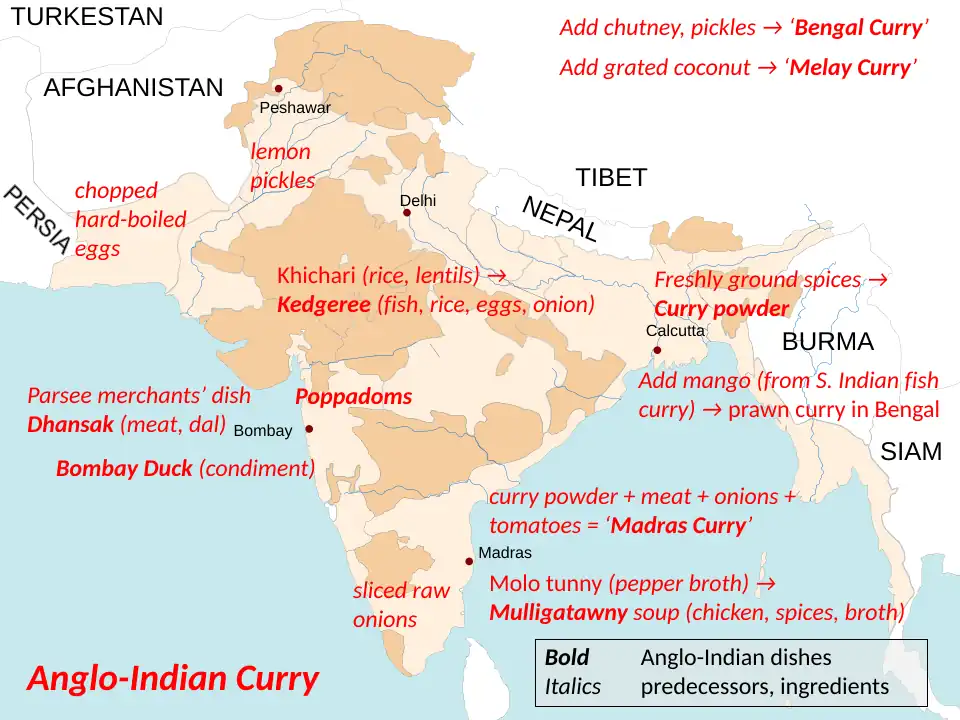

Anglo-Indian cooks created what they called curry by selecting elements of Indian dishes from all over British India. Collingham describes their taste as "eclectic", "pan-Indian", "lacking sophistication", and forming a "coherent repertoire".[12] She notes especially their "passion for garnishes", which they borrowed from multiple traditions: chopped hard-boiled eggs from Persian cuisine; lemon pickles from Punjab; pappadoms, dried coconut, and raw onions from South India; and pieces of fried bacon.[34]

Their Indian cooks ground spices afresh for each dish, but the Anglo-Indians created recipes for curry powders, different mixtures of spices. Ready-ground curry powder became available commercially in Britain by 1784, differentiating British from Anglo-Indian curries.[35] The basic approach to curry was to grind spices with garlic and onion, mix them to a paste with ghee (clarified butter), and simmer this with the meat. As this recipe returned to Britain, the fresh spices were replaced by curry powder, and the ghee with butter. Lizzie Collingham writes that variations were created with simple additions, such as of chutney and pickles to form "Bengal" curry, or grated coconut to make "Melay" curry.[36]

In her 1895 book Anglo-Indian Cooking at Home, Henrietta Hervey described how to make three curry powders, which she called "Madras", "Bombay", and "Bengal". The "Madras" powder recipe called for coriander, saffron, chilli, mustard seed, pepper, and cumin, among other ingredients. The "Bombay" recipe used coriander, cummin, turmeric, mustard seed, pepper, chillies, and a little fenugreek. The "Bengal" mixture consisted mainly of coriander, turmeric, fenugreek, ginger, black pepper, and chilli.[37] For cooks in England, Hervey suggested the commercial Crosse & Blackwell mixture, which she called "the nearest approach to the real article", but "a pis aller [a desperate measure[38]] at the best".[39] Hervey's recipe for "Country Captain" chicken curry for a British audience consisted of a chicken cut into joints, dusted with curry powder, and fried with onions;[40] Brown's recipe for the modern Anglo-Indian version of the dish calls for chillies, ginger, and black pepper in place of the curry powder.[41]

Chutney, one of the few Indian dishes—alongside curry—that has had a lasting influence on English cuisine according to The Oxford Companion to Food,[1] is a cooked and sweetened condiment of fruit, nuts or vegetables. It borrows from a tradition of jam-making where sour fruit and sugar are combined, the sour note being provided by vinegar.[42]

Puddings and sweets

Hervey gives recipes for several Anglo-Indian puddings. "'Bombay' Pudding" calls for slices of stale bread in egg custard and fried in ghee. Her coconut pudding consists of grated coconut with sugar, butter, and eggwhite, baked in the oven. "Raggi" pudding is ground finger millet boiled with milk, sugar, and flavourings, and baked. Her banana pudding uses roasted plantains, sliced and flavoured, and boiled in pudding paste. Her rice pudding is baked with milk and sugar, topped with butter and nutmeg.[37]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Davidson 2014, pp. 21–22

- ^ "Sustainable shore – October recipe – Year of Food and Drink 2015". nls.uk. National Library of Scotland. Archived from the original on 10 January 2018.

- ^ Roy, Modhumita (7 August 2010). "Some Like It Hot: Class, Gender and Empire in the Making of Mulligatawny Soup". Economic and Political Weekly. 45 (32): 66–75. JSTOR 20764390.

- ^ a b c Collingham 2007, p. 129.

- ^ Jahangir, Rumeana (26 November 2009). "How Britain got the hots for curry". British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

"Indian dishes, in the highest perfection… unequalled to any curries ever made in England." So ran the 1809 newspaper advert for a new eating establishment in an upmarket London square popular with colonial returnees.

- ^ "Curry house founder is honoured". BBC Online. 29 September 2005. Retrieved 21 March 2012.

- ^ The Epicure's Almanack, Longmans, 1815, pp. 123–124.

- ^ Metcalf 2014, p. 44.

- ^ Metcalf 2014, p. 56.

- ^ Rees, Lowri Ann (1 March 2017). "Welsh Sojourners in India: The East India Company, Networks and Patronages, 1760-1840". The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. 45 (2): 166. doi:10.1080/03086534.2017.1294242. S2CID 159799417. Retrieved 8 November 2023.

- ^ a b Maroney, Stephanie (23 February 2011). "'To Make a Curry the India Way': Tracking the Meaning of Curry across Eighteenth-Century Communities". Food and Foodways. 19: 129. doi:10.1080/07409710.2011.544208. S2CID 146364557.

- ^ a b c Collingham 2007, pp. 118–125, 140.

- ^ Bullock, April (2012). "The Cosmopolitan Cookbook". Food, Culture & Society. 15 (3): 439. doi:10.2752/175174412X13276629245966. S2CID 142731887.

- ^ Glasse, Hannah (1758) [1747]. The Art of Cookery made Plain and Easy. Edinburgh. p. 101.

- ^ Dickson Wright, Clarissa (2011). A History of English Food. Random House. pp. 304–305. ISBN 978-1-905-21185-2.

- ^ Kenney-Herbert, Arthur Robert (1994) [1885]. Culinary Jottings for Madras, Or, A Treatise in Thirty Chapters on Reformed Cookery for Anglo-Indian Exiles (Facsimile of 5th ed.). Prospect Books. ISBN 0-907325-55-6.

- ^ Singh, Rashmi Uday (26 April 2006). "Veeraswamy". Metro Plus Chennai. The Hindu. Archived from the original on 6 December 2007.

- ^ Gill, A.A. (23 April 2006). "Veeraswamy". The Times. London.

- ^ "Veeraswamy". Evening Standard. 27 February 2001.

- ^ Brennan, Jennifer (1990). Encyclopaedia of Chinese and Oriental Cookery. Black Cat.

- ^ Brennan, Jennifer (1990). Curries and Bugles, A Memoir and Cookbook of the British Raj. Viking. ISBN 962-593-818-4.

- ^ Burton, David (1993). The Raj at Table. Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0571143900.

- ^ "Fears for the decline of Anglo-Indian cooking". BBC News Online. 7 February 2011.

- ^ Brown 1998, p. 78.

- ^ Brown 1998, pp. 151–155.

- ^ Brown 1998, pp. 117, 126–127, 131–133, 137–138.

- ^ Brown 1998, pp. 395–398.

- ^ Brown 1998, p. 84.

- ^ Collingham 2007, p. 120.

- ^ Collingham 2007, pp. 119, 145.

- ^ Collingham 2007, pp. 116–117.

- ^ "pish-pash". Oxford Dictionaries. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

- ^ Frere, Catherine Frances, ed. (1909). The Cookery Book of Lady Clark of Tillypronie. London: Constable and Company. p. 153. OCLC 752897816.

- ^ Collingham 2007, pp. 119.

- ^ Collingham 2007, pp. 140–141.

- ^ Collingham 2007, p. 140.

- ^ a b Hervey 1895, pp. 39–41.

- ^ "pis aller". Vocabulary.com. Retrieved 18 August 2025.

- ^ Hervey 1895, p. 10.

- ^ Hervey 1895, p. 17.

- ^ Brown 1998, p. 120.

- ^ Bateman, Michael (17 August 1996). "Chutneys for Relishing". The Independent. Archived from the original on 7 May 2022. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

Sources

- Brown, Patricia (24 February 1998). Anglo-Indian Food and Customs. Penguin Books India. ISBN 0-14-027137-6.

- Collingham, Lizzie (2007). Curry: A tale of cooks and conquerors. Chapter 1: Chicken Tikka Masala: The Quest for an Authentic Indian Meal, Chapter 6: Curry Powder: Bringing India to Britain: Oxford University press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Davidson, Alan (2014). Tom Jaine (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Food (3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-967733-7.

- Hervey, Henrietta (1895). Anglo-Indian Cookery at Home. London: Horace Cox. ISBN 978-1-900318-33-4.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Metcalf, Barbara (2014). A Concise History of Modern India. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139207805. ISBN 9781139207805.

Further reading

- Chapman, Pat (1997). Taste of the Raj. London: Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 0-340-68035-0.

External links

- "Food Stories" Archived 10 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine – British Library