Biology of romantic love

| |||||||

The biology of romantic love has been explored by such biological sciences as evolutionary psychology, evolutionary biology, anthropology and neuroscience. Neurochemicals and hormones such as dopamine and oxytocin are studied along with a variety of interrelated brain systems which produce the psychological experience and behaviors of romantic love.

The study of romantic love is still in its infancy.[1] As of 2021, there were a total of 42 biological studies on romantic love.[2]

Definition of romantic love

The meaning of the term "romantic love" has changed considerably throughout history, making it difficult to simply define.[3][4] Initially it was coined to refer to certain attitudes and behaviors described in a body of literature now referred to as courtly love.[5] However, academic psychology and especially biology also consider romantic love in a different sense, which refers to a brain system (or systems) related to pair bonding or mating with associated psychological properties.[3][6][7][8]

Bode and Kushnick undertook a comprehensive review of romantic love from a biological perspective in 2021. They considered the psychology of romantic love, its mechanisms, development across the lifespan, functions, and evolutionary history. Based on the content of that review, they proposed a biological definition of romantic love:[6]

Romantic love is a motivational state typically associated with a desire for long-term mating with a particular individual. It occurs across the lifespan and is associated with distinctive cognitive, emotional, behavioral, social, genetic, neural, and endocrine activity in both sexes. Throughout much of the life course, it serves mate choice, courtship, sex, and pair-bonding functions. It is a suite of adaptations and by-products that arose sometime during the recent evolutionary history of humans.

Romantic love in this sense is also not necessarily "dyadic", "social" or "interpersonal", despite being related to pair bonding. Romantic love can be experienced outside the context of a relationship, for example in the case of unrequited love where the feelings are not reciprocated.[9][10] A person can develop romantic love feelings before any relationship has occurred, for only a potential partner.[9][10][11][7] The potential partner can even be somebody they do not know well or aren't acquainted with at all, as in cases of love at first sight and parasocial attachments.[9][12][13]

The early stage of romantic love (which has obsessive and addictive features) might also be referred to as being "in love", passionate love, infatuation, limerence or obsessive love.[11][14][6][15] Research has never settled on a unified terminology or set of methods.[6][2] Distinctions are drawn between this early stage of romantic love and the "attachment system" theorized by the attachment theorists like John Bowlby.[16][8][14] In the past, attachment theorists have argued that attachment theory and attachment styles can replace other theories of love, but academics on love have argued this is incorrect and that romantic love and attachment are not identical concepts.[17][14][16] The early stage of romantic love is thought to involve additional brain systems for other purposes, with distinct evolutionary histories.[16][11][8] Romantic love is also distinct from sexual attraction, although they most often occur together.[11][8][18]

Variation exists in the way romantic love is expressed in the population. A cross-cultural study of currently in-love people found four clusters, with varying degrees of intensity, obsessive thinking, commitment, frequency of sex and other differences.[19] Other studies indicate romantic love can be experienced both with or without obsessional features.[20][21] Typically, intense romantic love is limited to a duration of 12-18 months or as long as 3 years, depending on the estimate;[6][15] however, in a rare phenomenon called "long-term intense romantic love", some people experience intense attraction inside a relationship, even for 10 years or more. This is similar to early-stage intense romantic love, but at this later stage they exhibit less of the obsessional features.[20][21]

Independent emotion systems

Helen Fisher and her colleagues proposed that the brain systems involved with mammalian reproduction can be separated into at least three parts:[16][11]

Neuroscientists currently believe that the basic emotions arise from distinct circuits (or systems) of neural activity; that humans share several of these primary emotion-motivation circuits with other mammals; and that these brain systems evolved to direct behavior [...]. It is hypothesized that among these primary neural systems are at least three discrete, interrelated emotion-motivation systems in the mammalian brain for mating, reproduction, and parenting: lust, attraction, and attachment [...].

- Lust is the sex drive, or libido.

- Attraction (or early-stage romantic love, also called passionate love or infatuation) is associated with feelings of exhilaration, obsessive (or "intrusive") thoughts and the craving for emotional union.

- Attachment (the attachment system from attachment theory, and also called companionate love) is associated with feelings of calm, security and comfort, but separation anxiety when apart.[16][11][8]

In Fisher's theory, the systems tend to act in unison, but may become disassociated and act independently. For example, a person in a long-term partnership may feel deep attachment for their spouse, while experiencing intense romantic love (attraction) for some other individual, while being sexually attracted (lust) to still others, all at the same time.[22][11] Lisa Diamond has also used independent emotions theory to explain why people can 'fall in love' sometimes without sexual desire, as in the case of "platonic" infatuation for a friend.[18][23]

Fisher associates each system with different neurotransmitters and/or hormones (lust: estrogen & androgens; attraction: dopamine, norepinephrine & serotonin; attachment: oxytocin & vasopressin), but modern research shows these associations are not as clearly defined as Fisher's theory proposes.[11][8][6][24] Additionally, romantic love has been associated with endogenous opioids, cortisol and nerve growth factor, which are not included in Fisher's earlier model.[8][25][26] With respect to the idea that the systems are independent, a more modern theory holds that the attachment system is active in early-stage romantic love, in addition to the infatuation component. Fisher's model is considered outdated, although the idea of interrelated systems is useful.[8]

Evolution of systems

Evolutionary psychology

Evolutionary psychology is seen as an organizing framework which offers explanations behind psychological functions (rather than merely describing them), as well as specifying theoretical constraints, like requiring that a given trait is adaptive in the form of providing reproductive benefit to an individual.[27] Evolutionary psychology has proposed a variety of explanations for romantic love.[28][29]

- Romantic love is a powerful commitment device.[6][30] Romantic love suppresses the search for alternative mates (even irrationally so, when a more desirable one comes along), and signals this to the partner.[30][31][32] Romantic love may also signal to alternative mates, disincentivizing them from pursuing oneself.[33] The emergence of longer pair bonds in the evolution of humans coincided with the emergence of concealed ovulation, where it cannot (in general) be determined when a woman is ovulating, requiring partners to stay together while having sex during the entire menstrual cycle. Commitment is seen as adaptive to facilitate this, and to facilitate child care.[31][30] Love feelings might be the psychological reward produced by the brain when the problem of commitment is being solved.[34]

- Romantic love signals parental investment.[29] Paternal investment in the form of pair bonds has been linked to better outcomes for children, both as infants and as they grow older. Children raised in pair bonds are more socially competitive and more likely to survive to reproductive age.[35]

- Successful pair bonding predicts better health and survival.[30] Happy, well-functioning romantic relationships contribute to mental and physical health, especially when stress is encountered. The end of a pair bond (e.g. divorce) is associated with vulnerability, such as to disease, depression, substance abuse, or negative outcomes for children. Victims of a heart attack, for example, are more likely to have another when they live alone.[30][36]

- Romantic love may have evolved to override rationality, so that one reproduces regardless of the considerable costs of raising a child, and regardless of any rational will to be single or child-free.[37]

- Being in love makes people more creative, so romantic love may have evolved as a courtship display. It has been suggested that art, music and literature serve a function like a peacock's tail, but as a display of mental prowess, designed to impress and make a potential partner swoon. Creativity is believed by some authors to be especially a part of the male courtship display.[38]

- Romantic love may conserve time and metabolic energy by focusing courtship efforts on a specific individual over others.[7]

- Monogamous pair bonding helps prevent sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) which compromise fertility, especially for women. Certain STDs (e.g. syphilis) increase the risk of miscarriage, and otherwise harm or can be passed to an unborn child. The strongest predictor of contracting an STD is the number of sexual partners, so limiting this is the best way to limit the risk of contracting a disease which would harm one's reproductive health.[39]

- Romantic love promotes exclusivity via mate guarding.[29] Romantic jealousy is one of the most common correlates of being in love, which evolved as a protection from the threat of losing one's love to a romantic rival.[40] Jealousy is seen as adaptive (when it motivates one to maintain their relationship) up to a point, but can also take the form of pathological jealousy where a sufferer has a delusional or paranoid belief in their partner's infidelity regardless of actual evidence.[41]

Time of evolution

Although the exact moment during human evolution is unknown, modern romantic love is usually believed to have evolved either during or after the time of bipedalism.[8][6] The earliest hominid found with extensive evidence of bipedalism (and some evidence of pair bonding) is Ardipithecus ramidus, from about 4.4 million years ago, although it may also be the case that bipedalism is older than this.[42][43][8] It has been proposed that monogamous pair bonding (which is rare among mammals) evolved during this time, because walking bipedally requires mothers to carry infants in their arms or on their hip, instead of on their backs. With their hands occupied, mothers would be more vulnerable, requiring additional help for food and protection from males of the species (hence, husbands or fathers).[44] A different selection pressure which has been proposed is the evolution of infant altriciality (immaturity and helplessness) and large brain size at birth, which occurred around 2 million years ago.[8] At this time, brain size became so large that a fully-developed infant's head could not fit through the mother's pelvic birth canal (known as the obstetricial dilemma), requiring the infant to be born early and underdeveloped in comparison to other species. This would have also placed a greater burden on mothers, and made paternal support more valuable.[45][46]

Due to the general scarcity of evidence, it is still also possible that romantic love (or a precursor to it) predated bipedalism and altriciality, possibly originating in a common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees, 5-8 million years ago. While chimpanzees primarily mate opportunistically, some of their rarer reproductive strategies have features reminiscent of romantic love (involving mate guarding, and a more-than-fleeting association).[8][6] One assumption behind hypotheses based on fossil evidence is that less sexual dimorphism in body mass (i.e. similarity) is indicative of monogamy, but the comparative similarity between the sexes in human body mass occurred as recently as 500,000 years ago. This suggests that there may have been multiple steps in the evolution of human pair bonding, and romantic love may have evolved during any of these periods.[8][6]

Courtship attraction

Helen Fisher's theory is that romantic love (which she considers distinct from attachment) is a motivation system for choosing and focusing energy on a preferred mating partner. According to Fisher, this brain system evolved for mammalian mate choice, also called "courtship attraction". In this phenomenon, a preferred mating partner is chosen based on a display of physical traits (such as a peacock's tail feathers) or other behaviors.[16][11][7] Fisher also includes the attraction to personality traits and other characteristics in her mate choice theory for humans.[47][48][49] Courtship attraction shares similar behaviors with romantic love in humans, and both involve activation of dopaminergic reward circuits. In most species, courtship attraction is as brief as lasting only minutes, hours, days or weeks, but intense romantic love can last much longer in humans.[7] Fisher believes that during the timeline of human evolution, mammalian courtship attraction may have become prolonged and intensified as pair bonding evolved, eventually becoming the phenomenon of romantic love today.[15]

A critique of Fisher's theory published by Adam Bode holds that courtship attraction only encompasses love at first sight attraction or a crush, and the core components of romantic love (including the intense attraction and obsessive thoughts, in addition to attachment) evolved as a co-option of mother-infant bonding.[8] A study on love at first sight found that even though people reporting the experience retrospectively will recall features resembling passionate love ("constant thoughts about the person and the desire to be with him or her"), people reporting love at first sight currently after just meeting the potential partner only report neutral scores (neither agreeing nor disagreeing) on a romantic love measure including a passion component. Some authors have speculated that the remembered account of falling in love at first sight (with high passion) is often actually a memory confabulation. Furthermore, the study found that the experience of love at first sight was related to the physical attractiveness of the potential partner. This led the researchers to conclude that love at first sight is actually a strong initial attraction, rather than resembling the state of being in love.[13] Bode argues this more closely resembles the concept of courtship attraction, and can be considered a separate system from core romantic love components. Courtship attraction may be characterized by dopamine, oxytocin and opioid activity, but little is known about it because existing studies were not designed to target it.[8]

Co-option of mother-infant bonding

Co-option is an evolutionary process whereby a given trait is repurposed to take on a new function.[50][8][6] One example is how a number of species of fish (e.g. catfish) have co-opted their gas bladder to produce sound. Co-opted traits can be morphological, but also behavioral. Co-option has been used as an explanation of how a species can develop an evolutionary adaptation very quickly sometimes, seemingly faster than Darwinism could explain. With this process, a seemingly "new" trait can develop quickly because its structure predated the time of adaptation, only needing to be modified to function in a new way. In some cases, co-option involves one gene whose function is altered, while in other cases the co-opted gene is a duplicate and the function of the original gene is retained.[50] The terms "co-option" and "exaptation" are closely related, but have different connotations. Exaptation refers to structural continuity when a trait takes on a new function.[50][8]

Adam Bode has proposed that romantic love is "a suite of adaptations and by-products" consisting of a number of interrelated systems, several of which evolved by co-opting mother-infant bonding (attraction for bonding, obsessive thinking and attachment). The co-option theory says that the genes that regulate mother-infant bonding were recreated and took on a new function. Courtship attraction and sexual desire are "causally linked adjuncts" which were not co-opted, but were combined and modified in romantic love. The theory is based on the available human evidence, but also a literature arising from research on prairie voles that pair bonding uses the same mechanisms that mother-infant bonding uses.[8][6]

Academic literature has drawn a parallel between romantic love and the mother-infant dyad since the 1980s, with attachment theorists like Cindy Hazan and Phillip Shaver believing the two share a common biological process.[51] In 1999, James Leckman & Linda Mayes compared features of romantic love and early parental love, finding substantial similarities. Both are altered mental states featuring preoccupations, exclusivity of focus, a longing for reciprocity and idealization of the other. The trajectories of both also share similarities, with preoccupation increasing during courtship (for romantic love) and around the time of birth (for parental love), then diminishing after a relationship is established (for romantic love) or shortly after the postpartum period (for parental love).[52][8][6] (The use of "baby talk" by romantic lovers is another "uncanny" similarity.)[8] In 2004, Andreas Bartels and Semir Zeki were the first to compare romantic love and maternal love with fMRI. This comparison looked at areas known to contain high densities of receptors for the attachment hormones oxytocin and vasopressin. Bartels & Zeki found precise overlap in some specific areas including the striatum (putamen, globus pallidus and caudate nucleus) and some overlap in the ventral tegmental area, areas with dopamine and oxytocin receptors. Each type of love was also associated with other unique activations. Notably, maternal love involved the periaqueductal gray matter, an area associated with endogenous pain suppression during intense emotional experiences such as childbirth.[53][54][8] Two meta-analyses of fMRI experiments have also found similarities between maternal love and romantic love.[55][54][8] A 2022 meta-analysis by Shih et al. found that both types of love were associated with the left ventral tegmental area (more associated with the pleasurable aspect of reward, or "liking"), while in addition romantic love also involved the right ventral tegmental area (more associated with reward "wanting").[54]

In 2003, Lisa Diamond suggested that adult pair bonding is an exaptation of the affectional bond between infants and caregivers, using this to explain instances of "platonic" infatuations, or i.e. "romantic" passion without sexual desire.[56][18] Some instances of this are reported by Dorothy Tennov in her study of "limerence" (i.e. love madness, commonly for an unreachable person), in which a younger woman who otherwise considered herself heterosexual would have this type of reaction towards an older woman.[56][57][58][59] Among other examples are schoolgirls falling "violently in love with each other, and suffering all the pangs of unrequited attachment, desperate jealousy etc." (historically called a "smash"), and Native American men who seemed to fall in love with each other and form intense, but non-sexual bonds. Helen Fisher's theory that sexual desire is a separate system from romantic love and attachment is also given as theoretical evidence. Diamond argues that romantic love without sexual desire can even happen in contradiction to one's sexual orientation: because it would not have been adaptive for a parent to only be able to bond with an opposite sex child, so the systems must have evolved independently from sexual orientation. People most often fall in love because of sexual desire, but Diamond suggests time spent together and physical touch can serve as a substitute. Diamond believes the connection between romantic love and sexual desire is "bidirectional" in that either one can cause the other to occur because of shared oxytocin pathways in the brain.[18]

New model

Based on contentions over evolutionary theories and Fisher's outdated neurochemical model, Bode has suggested Fisher's model, while useful and the predominant one for a time, is oversimplified and proposes five systems:[8]

- Sexual desire is associated with a drive to initiate and be receptive to sexual activity. Testosterone, dopamine, serotonin, norepinephrine, acetylcholine, histamine and opioids have been implicated in sexual behavior.

- Courtship attraction is for choosing and focusing energy on a preferred mating partner and promotes courtship behaviors. It can take the form of e.g. love at first sight attraction or a crush and also be intertwined with other forms of attraction, but might not precede a relationship in all cases. Courtship attraction may be associated with dopamine, oxytocin and opioids.

- Bonding attraction is the type of attraction for pair bond formation, characterized by a strong desire for proximity, separation anxiety when apart, exclusivity of focus and heightened awareness of the loved one. Bonding attraction is associated with dopamine and oxytocin activity, especially in the ventral tegmental area. According to Bode's arguments, this is the type of romantic attraction shown in fMRI experiments of early-stage romantic love.

- Obsessive thinking involves preoccupation or intrusive thinking about the loved one. Some authors have drawn a comparison between this feature and obsessive-compulsive disorder, suggesting they share similar neurobiology, but the evidence for that is limited and ambiguous.

- Attachment is for pair bond maintenance, or maintaining very close personal relationships, with psychological features like a heightened sense of responsibility, longing for reciprocity and a powerful sense of empathy. Attachment is associated with oxytocin, dopamine and opioid activity, but there is also some evidence for the involvement of vasopressin.

Bode suggests that the systems of bonding attraction, obsessive thinking and attachment (the three systems which were co-opted from mother-infant bonding) together form the core of romantic love (the necessary components). However, all five systems are merged into one single phenomenon of romantic love, with a variety of different outcomes depending on the circumstances.[8]

Mechanics

Reward, motivation and addiction

The early stage of romantic love is being compared to a behavioral addiction (i.e. addiction to a non-substance) but the "substance" involved is the loved person.[60][61][15][62] Addiction involves a phenomenon known as incentive salience, also called "wanting" (in quotes).[63][64] This is the property by which cues in the environment stand out to a person and become attention-grabbing and attractive, like a "motivational magnet" which pulls a person towards a particular reward.[65][64] Incentive salience differs from craving in that craving is a conscious experience and incentive salience may or may not be. While incentive salience can give feelings of strong urgency to cravings, it can also motivate behavior unconsciously, as in an experiment where cocaine users were unaware of their own decisions to choose a low dose of cocaine (which they believed was placebo) more often than an actual placebo.[66] In the incentive-sensitization theory of addiction, repeated drug use renders the brain hypersensitive to drugs and drug cues, resulting in pathological levels of "wanting" to use drugs.[62][64] People in love are thought to experience incentive salience in response to their beloved. Lovers share other similarities with addicts as well, like tolerance, dependence, withdrawal, relapse, craving and mood modification.[15]

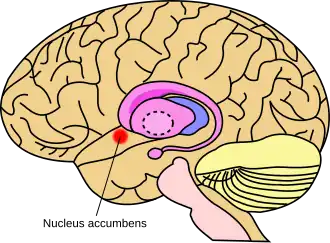

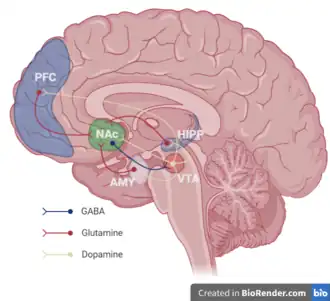

Incentive salience is mediated by dopamine projections in the mesocorticolimbic pathway of the brain, an area generally involved with reward, motivation and reinforcement learning.[63][64][67][21] Dopamine signaling for incentive salience originates in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and projects to areas such as the nucleus accumbens (NAc) in the ventral striatum.[68][64] The VTA is one of two main areas of the brain with neurons which produce dopamine (the other being the substantia nigra pars compacta). Projections from the VTA innervate the NAc, where dopamine activity attaches motivational significance to stimuli associated with rewards.[69] Brain scans of people in love using fMRI (commonly while looking at a photograph of their beloved) show activations in these areas like the VTA and NAc.[15][62][54] Another dopamine-rich area of the reward system shown to be active in romantic love is the caudate nucleus, containing 80% of the brain's dopamine receptor sites, located in the dorsal striatum.[15][21][70][71] The caudate nucleus has shown activity in response to a monetary reward and cocaine.[70][72][53] This activity in reward and motivation areas suggests that early-stage intense romantic love is a motivation system or goal-oriented state (rather than a specific emotion), consistent with the description of romantic love as a desire or longing for union with another person.[70][62][21] These activations are also consistent with the similarity between romantic love and addiction.[15][62]

In addiction research, a distinction is drawn between "wanting" a reward (i.e. incentive salience, tied to mesocorticolimbic dopamine) and "liking" a reward (i.e. pleasure, tied to hedonic hotspots), aspects which are dissociable.[65][64] People can be addicted to drugs and compulsively seek them out, even when taking the drug no longer results in a high or the addiction is detrimental to one's life.[15] They can also "want" (i.e. feel compelled towards, in the sense of incentive salience) something which they do not cognitively wish for.[65] In a similar way, people who are in love may "want" a loved person even when interactions with them are not pleasurable. For example, they may want to contact an ex-partner after a rejection, even when the experience will only be painful.[15] It is also possible for a person to be "in love" with somebody they do not like, or who treats them poorly.[73]

Academics have proposed a number of theories for how addictions begin and perpetuate.[66] One prominent theory developed by Wolfram Schultz involves a dopamine signal which encodes a reward prediction error (RPE): the difference between the predicted value of a reward which would be received by performing a particular action and the actual value upon receiving it (i.e. whether the reward was better, equal to or worse than expected).[74][62][75] In this theory, dopamine is also part of a mechanism for reinforcement learning which associates rewards with the cues which predicted them. Drugs of abuse like cocaine hijack this mechanism by artificially overstimulating dopamine neurons, mimicking an RPE signal which is much stronger than could be produced naturally.[74] An alternative model developed by Kent Berridge and Terry Robinson states that dopamine signaling causes the motivational output (incentive salience) which is proportional to RPE, but that the dopamine signal itself may be an effect of learning rather than causing it directly.[76][65][66] There is, however, said to be overwhelming evidence that dopamine guides learning in addition to motivation.[77] The computation of dopamine signaling is complicated, with inputs from a variety of areas in the brain, although its output (primarily from the VTA) is a relatively homogeneous signal encoding the level of RPE.[78][77] One study has investigated whether people in long-term romantic relationships experienced RPE in response to having expectations about their partners' appraisal of them validated or violated, indicating they do. This study used fMRI to find that reward areas like the VTA and striatum responded in a way consistent with other research on RPE.[79] Most fMRI studies of romantic love have had participants look at a photograph, and the resulting reward system activity has been interpreted in terms of salience.[54][15][62]

Research has not investigated whether romantic love shares all of the neurobiological aspects of addiction.[6][80] Despite similarities, there are also differences between romantic love and addiction. One of the major differences is that the trajectories diverge, with the addictive aspects tending to disappear over time during a relationship in romantic love. By comparison, in a drug addiction, the detrimental aspects magnify over time with repeated drug use, turning into compulsions, a loss of control and a negative emotional state.[62][63] It has been speculated that the difference between these could be related to oxytocin activity present in romantic love, but not in addiction.[62] Academics do not universally agree on whether or not love is always an addiction or when it needs to be treated.[80] The term "love addiction" has had an amorphous definition over the years and does not yet denote a psychiatric condition, but recently one definition has been developed that "Individuals addicted to love tend to experience negative moods and affects when away from their partners and have the strong urge and craving to see their partner as a way of coping with stressful situations."[81] Other authors include rejected lovers as love addicts,[82] or specify that love is an addiction when it involves abnormal processes which carry negative consequences. A broader view is that all love is addiction, or simply an appetite, similar to how humans are dependent on food.[80] Research on behavioral addictions is more limited than research on drugs of abuse; however, there is a growing body of evidence that some people are susceptible to showing brain patterns in response to natural rewards (food, sex, etc.) similar to drug addicts, particularly in the case of gambling addiction.[66][83] Romantic love may be a "natural" addiction, which differs from the nature of drug addiction in that love may be prosocial and has been evolved for the purpose of pair bonding.[62][15] Helen Fisher, Arthur Aron and colleagues have proposed that romantic love is a "positive addiction" (i.e. not harmful) when requited and a "negative addiction" when unrequited or inappropriate.[15]

Oxytocin, bonding and attraction

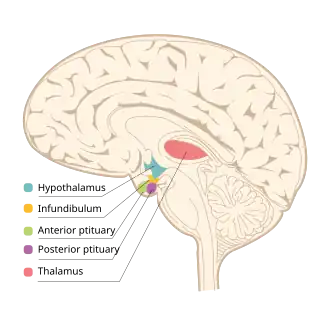

Oxytocin is sometimes called the "love hormone", because of its involvement in the mechanisms of maternal behavior and adult pair bonding. Oxytocin is synthesized primarily in an area of the hypothalamus and released into the blood via the pituitary gland, where it's been found circulating in people in the early stages of romantic love.[75][8][84] Additionally, the hypothalamus projects oxytocin to other areas of the brain, like the ventral tegmental area (VTA), nucleus accumbens (NAc), amygdala and hippocampus. The projections to reward areas (VTA and NAc) are thought to modulate social salience, or i.e. the level of dopamine activity in response to socially-relevant stimuli.[75][1] This oxytocin signaling in reward pathways may also be the source of salience in response to a loved one.[1] In humans, circulating oxytocin levels have been associated with higher levels of interaction between partners, and also predicted which couples would still be together 6 months later.[75] Anna Machin calls the combination of oxytocin and dopamine the "glue" which makes the early stages of a relationship possible.[85]

The role of oxytocin in human behavior is varied and complex.[84] Oxytocin lowers inhibitions to forming new relationships by deactivating the amygdala, involved with processing fear and anxiety.[86] Oxytocin can be released with physical touch, hence it's also sometimes called the "cuddle hormone".[18][87][84] Oxytocin also plays a role in sexual behavior, being released during sexual arousal and orgasm.[75] Aside from romantic and parental bonding, oxytocin activity has a role in the interactions with peers or strangers, for example facilitating facial recognition and eye contact. Oxytocin is believed to facilitate trust and altruistic behaviors towards in-groups (e.g. partners or children), but also aggression towards out-groups (e.g. strangers or conspecifics).[75]

Much of the research on oxytocin comes from experiments on monogamous prairie voles (notably by Larry Young),[88] but this research is also used for making inferences about humans.[75][8][84] In prairie voles, both oxytocin and dopamine signaling have been shown to influence pair bond development. For example, the number of oxytocin receptors in the NAc is positively related to how fast a partner preference is formed. A partner preference can also be prevented by injecting either a dopamine or oxytocin receptor antagonist (a drug which blocks transmission) into the NAc of a prairie vole directly.[75]

In a contemporary model of the brain systems involved with romantic love, this type of salience (or 'bonding attraction') is present throughout the entire time a person is experiencing romantic love, including during the early stages. This contrasts with some previous theories (e.g. proposed by Helen Fisher in 1998) which stated that oxytocin activity and dopamine activity were distinct (and independent) systems, and that oxytocin activity only became prominent at some later stage of a relationship.[8][16][11] Levels of oxytocin would still vary from situation to situation because of differing types of stimuli, for example because of less regular interaction and physical touch in cases of unrequited love. This could be used to explain some of the maladaptive symptoms of infatuation (e.g. sleep difficulties, social anxiety, clammy hands, etc.), when dopaminergic activity is high without the calming effect of oxytocin from the attachment system.[8]

Brain opioid theory of social attachment

Modern research is increasingly showing the importance of endogenous opioids in love and social attachment, particularly the β-endorphin (the most potent endogenous opioid) and the μ-opioid receptor system.[8][26][89][90] While opioids have their origin being the body's natural painkiller, they're also implicated in a variety of other systems, essentially like neurotransmitters.[26][91] Opioid receptors are located throughout the brain, including in the limbic system (affecting basic emotions) and neocortex (affecting more conscious decision-making).[92] Opioids are linked to the consummatory part of reward, or i.e. "liking" or pleasure, and released in areas of the brain called hedonic hotspots (or pleasure centers). Hedonic hotspots are located in the nucleus accumbens, the ventral pallidum and other areas.[26][89][68] This function includes social reward, or the pleasurable aspect of social interactions.[26] The brain opioid theory of social attachment (BOTSA) is a long-running theory summarizing this connection, originally conceived of in the 1970s, based on a proposal by the psychiatrist Michael Liebowitz and research by the neuroscientist Jaak Panksepp. Starting in the 1990s, opioids were overshadowed by the interest in oxytocin and largely overlooked until more recently, possibly because of the difficulty studying them (requiring e.g. a PET scan, which is expensive).[26] Opioids have been connected to a variety of social experiences, including the early stage of romantic love and attachment styles.[90][26][25] While the addictive aspects of love have been compared to cocaine or amphetamine addiction, other aspects may also resemble an opioid addiction.[8]

BOTSA (as it was originally conceived of) predicts that in the absence of social relationships, individuals will have comparatively lower levels of endogenous opioids, motivating them to initiate contact with other people. Social contact then leads to feelings of euphoria and contentment, but individuals also need to continue contact to avoid withdrawal symptoms.[26] Liebowitz originally argued that romantic relationships resemble narcotic addiction, and that individual neurochemical differences could also explain why some people are unable to commit, or stay in abusive relationships.[26] Earlier experiments on BOTSA were animal studies, but in the 2000s this has been expanded to include human experiments.[26][90]

Among the animal studies which have been done, there's some evidence that separation distress is akin to opioid withdrawal. Studies on chicks, puppies, Guinea pigs, rats, sheep and monkeys have shown that administrating morphine reduces distress vocalizations when separated from the mother, and administrating naloxone (an opioid antagonist) increases them, even in the presence of other members of the same species.[26] In another study, mutant mouse pups with a μ-opioid receptor knockout (lacking the μ-receptor gene) vocalized less frequently in response to isolation than normal mice. Administration of morphine had no effect on distress vocalization frequency in the knockout mice, despite reducing it in normal mice. Furthermore, these knockout mice had a reduced preference for their mother's odor, which is normally the result of conditioning mediated by the endogenous opioid system.[93][26] In nonhuman primates, studies have suggested that endogenous opioids provide the euphoria behind dyadic social grooming behaviors.[26][94] Other animal studies have shown that endogenous opioids play a role in the desire for rough-and-tumble play (a physical, but also social behavior).[26] In humans, physical activity with a social element (rowing, dancing, laughing) increased pain tolerance more when the activities were synchronized with other people.[95]

An fMRI experiment in 2010 investigated whether viewing a picture of a romantic partner could reduce pain sensitivity, and which areas of the brain became active. Participants were exposed to high temperatures (resulting in moderate or high pain levels) while viewing a picture of a romantic partner (whom they were intensely in love with), or a friend, or performing a word association task which has also been shown to reduce pain via distraction. Participants were then asked to rate how much pain they felt on a pain scale, and both viewing a romantic partner and performing the distraction task (but not viewing a friend) were found to reduce pain levels. The fMRI scans revealed that viewing a romantic partner activated reward circuits in the brain, while the distraction task did not. Brain areas were also correlated with pain relief to reveal that reward analgesia and distraction analgesia involved distinct areas. Some areas associated with sensory processing of pain also had decreased activity while viewing a romantic partner.[25][26] Another earlier experiment showed that viewing photos of a romantic partner reduced experimental pain, but did not pair it with a brain scan.[25] A PET scan experiment in 2016 investigated whether non-sexual social touching between romantic partners was mediated by endogenous opioid activity. This study found that social touch did have an effect, but unexpectedly found that social touching decreased opioid activity in the brain rather than increasing it (despite being rated as pleasurable by participants). This is in contrast with prior PET research that pleasant affect is related to increased opioid activity. One possible explanation is that touching decreases stress, so this might also decrease the ongoing opioid activity in response to distress and pain. As this is also at odds (to some extent) with primate studies on grooming, there may be some variation between species in how opioids are involved with social reward.[96] Other modern studies on humans include blood plasma levels,[97] genetics[98] and studies with drugs like morphine and naltrexone to see how they change social perception and behavior.[89]

Obsessive thinking

Obsessive thinking about a loved one has been called a hallmark or a cardinal trait of romantic love,[8][99] ensuring that the loved one is not forgotten.[100] Some reports have been made that people can even spend as much as 85 to 100% of their days and nights thinking about a love object.[101] One study found that on average people in love spent 65% of their waking hours thinking about their beloved.[102] Another study used cluster analysis to find several different groups of lovers, with the least intense group spending 35% of their time on average and the most intense at 72%.[19] Since the late 1990s, these obsessional features have been compared to obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD).[16][52][103] This is also sometimes paired with a theory that obsessive (or intrusive) thinking is related to serotonin levels being lowered while in love, although study results have been inconsistent or negative.[16][103][6][104] Another theory relates obsessive thinking to addiction, because drug users exhibit obsessive thoughts about drug use, as well as compulsions.[62][60][63]

In 1999, James Leckman and Linda Mayes published a theoretical comparison between early-stage romantic love, early parental love and OCD. This paper was intended as an investigation into the origin of OCD, but it also relates to the evolutionary theory of romantic love.[52][8] Both early-stage romantic love and OCD share features of preoccupation, intrusive thoughts, a heightened sense of responsibility, a need for things to be "just right" and some proximity-seeking behaviors. In some cases, obsessions experienced by OCD patients relate to what harms might happen to a family member, which resembles some behavioral patterns involved with romantic and parental love. The authors also speculate that psychasthenia (feelings of incompleteness, insufficiency or imperfection) resembles the "longing for reciprocity" and idealization which are features of romantic love.[52]

Two experiments have investigated whether there's a relationship between romantic love and serotonin levels, by taking different measures using blood samples.[102][6] Although serotonin levels in the central nervous system would actually be the measure of interest, it has been assumed that measures of peripheral serotonin can be used as a marker for this.[102] A 1999 experiment led by Donatella Marazziti found that people in love had platelet serotonin transporter (SERT) density which was lower than controls, and similar to the density of a group of unmedicated OCD patients. Six of the 20 in-love participants were also retested after a period of 12 to 18 months, and SERT density had returned to normal.[103] However, because Marazziti's experiment looked at SERT (rather than serotonin directly), this makes it ambiguous whether serotonin levels were actually higher or lower. SERT transports serotonin from blood plasma back into the platelets, so that a reduction in SERT could correspond to an increased plasma level.[102][6] Another experiment in 2012 led by Sandra Langeslag which looked at blood serotonin levels found a contradictory result, with men and women being affected differently. Men had lower serotonin levels than controls, but women had higher serotonin levels. In women, obsessive thinking was also actually associated with increased serotonin.[102] A 2025 study led by Adam Bode also found no association between SSRI use and obsessive thinking about a loved one, or the intensity of romantic love. Therefore, although the earlier experiments do suggest romantic love and serotonin are probably associated, the authors suggest that the idea of obsessive thinking being attributed to lowered serotonin levels seems inaccurate.[104]

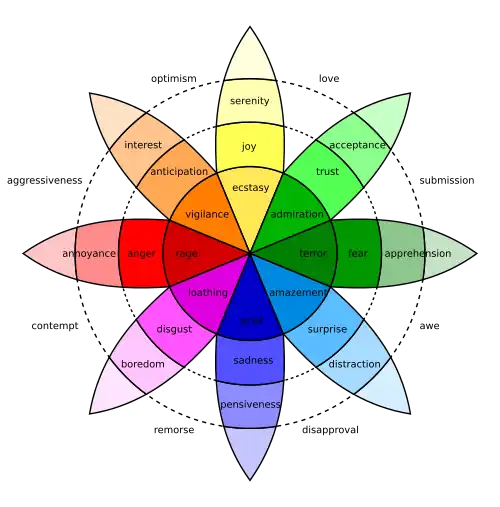

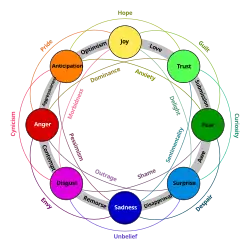

Emotional valence

Rather than being a specific emotion itself, romantic love is believed to be a motivation or drive which elicits different emotions depending on the situation: positive feelings when things go well, and negative feelings when awry.[9][70][105] Reciprocated love may elicit feelings of joy, ecstacy or fulfillment, for example, but unrequited love may elicit feelings of sadness, anxiety or despair.[9][106] A 2014 study of Iranian young adults found that the early stage of romantic love was associated with the brighter side of hypomania (elation, mental and physical activity, and positive social interaction) and better sleep quality, but also stronger symptoms of depression and anxiety. Those authors conclude that romantic love is "not entirely a joyful and happy period of life".[107] Romantic love may be either pleasant or unpleasant, regardless of the intensity level.[108][109] One of Dorothy Tennov's interview participants recalls being in love this way: "When I felt [Barry] loved me, I was intensely in love and deliriously happy; when he seemed rejecting, I was still intensely in love, only miserable beyond words."[109] The intensity of love feelings is also distinct from whether an individual is satisfied with their relationship (although the measures have been shown to be related to some extent). One can be satisfied with their relationship because it fulfills some other need besides love for their partner (like money or child care), or conversely be in love with an abuser in an abusive relationship.[9]

Unrequited love is common among young adults, although what purpose it serves (if any) is not understood. In one study, 63% of respondents reported having a "huge crush" at least once in the past 2 years but not letting the person know, and unrequited love was four times more frequent than equal love.[10] Another study found that 92.8% of participants reported at least one "powerful or moderate" experience of unrequited love in the past 5 years.[110] In 2010, Helen Fisher, Arthur Aron and colleagues published their fMRI experiment investigating which areas of the brain might be active in recently-rejected lovers. Participants had been in a relationship with their ex-partner for an average of 21 months, and then were post-rejection for an average of 63 days at the time of the experiment.[111] These participants reported spending more than 85% of their waking hours thinking of their rejector, reported a lack of emotional control, and exhibited unhappiness, with sometimes more extreme emotions like depression, anger, and even paranoia in pre- and post-interviews.[111][112] Similar to other fMRI experiments, the scan while looking at a photograph of the rejecting partner showed activations in dopaminergic reward system areas, like the ventral tegmental area and nucleus accumbens. These activations were also stronger than in a previous experiment of participants who were happily in love. The nucleus accumbens, prefrontal cortex and orbitofrontal cortex which were active have been associated with assessing one's gains and losses, and areas of the insular cortex and anterior cingulate cortex which were active have been involved with physical pain and pain regulation (respectively) in other studies.[111][15]

Stress and physiological arousal

In the early stages of romantic love, individuals may start out hypervigilant (hyperaware and sensitive to a partner's cues) due to uncertainty and novelty, but become synchronized over time as a relationship progresses. Bonding is thought to be in part facilitated by coordinated behaviors which display reciprocity and events which evoke beneficial stress (eustress), like a passionate kiss. The stress response system involves two major systems: the autonomic nervous system and the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis.[113] Some experiments have been done which support the idea that the stress response is involved during the early stage of romantic love, measuring cortisol levels; however, these experiments have been inconsistent with respect to cortisol being higher or lower.[114][113][6]

Positive illusions

People in love tend to overemphasize the positive aspects of their loved one or relationship, while overlooking or devaluing negative aspects.[115][116][6] This is regarded as a type of cognitive bias called positive illusions.[6][117][118] The phenomenon has also been referred to as crystallization,[115] idealization,[117] "love is blind" bias,[6] putting the loved one on a pedestal,[119] or seeing through rose-colored glasses.[120] In the past, some authors have depicted the phenomenon as a malady, arguing that people who idealize would have their partner fall short of their high expectations as a relationship progresses; however, despite this, significant modern scientific evidence has shown that positive illusions actually contribute to relationship satisfaction, long-term well-being and decreased risk for relationship discontinuation.[117][118][115]

The exact mechanism is not currently understood, but some brain areas are proposed to be related.[118][6] The dopaminergic areas of the reward system which are active in romantic love may be involved with attributing salience to the positive characteristics of a loved one. The dorsal anterior cingulate cortex is involved with error detection and has been active during negative social evaluation and exclusion, so that reduced activation of this area would be an adaptive response to a partner's negative characteristics. Certain areas of the prefrontal cortex could also be exerting top-down control to suppress emotional responses to attractive alternatives. Information is then passed to the orbitofrontal cortex, where positive and negative information is weighed, resulting in a biased subjective value about the partner.[118]

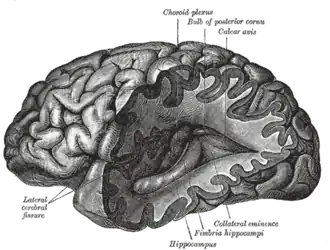

Brain imaging

Brain imaging techniques such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and positron emission tomography (PET) have been used to investigate which brain regions are involved in romantic love. Nearly all of these experiments have had participants look at a photograph of their beloved during an fMRI scan, with a few exceptions, although the specific procedures used have not always been identical. The differences in experimental design (e.g. length of time the participants had been in love, or the specific task given to participants during the scan) can be used to explain why the experiment results are sometimes different.[99][111][121][54][122]

In 2000, a study by Andreas Bartels and Semir Zeki of University College London was the first fMRI study of romantic love.[123] The 17 participants were "truly, deeply and madly in love", had been together for a mean of 2.4 years, and were shown either one or two photographs of their loved one during the scan. Two main areas were active in this study: the middle insular cortex, associated with stomach churning or "gut feelings", which could have something to do with the feeling of "butterflies in the stomach", and part of the anterior cingulate cortex, associated with feelings of euphoria. Other activations were areas in the cerebrum, the caudate nucleus, putamen and the cerebellum.[72][124][125] A later analysis in 2004 by the same authors also reports activity in the ventral tegmental area (VTA), which produces dopamine.[53][99] The study also showed key deactivations, areas of the brain that were less active in romantic love compared to friendship love, in the amygdala and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC). The amygdala is involved with fear and risk detection, and the mPFC is involved with understanding and predicting the intentions of other people, called mentalizing. These deactivations are taken as evidence that "love is blind", or i.e. that people in love discount the risks involved and misunderstand people's intentions, even leading to folly sometimes.[126]

In 2005, a study by Arthur Aron, Helen Fisher, Debra Mashek, Greg Strong, Haifang Li and Lucy Brown was the first fMRI study of early-stage intense romantic love.[99][127] It has been praised as advancing the scientific understanding of infatuated love, even by a skeptic of fMRI literature.[127] This study differed from Bartels & Zeki in that the 17 participants who had "just fallen madly in love" had been in love for a much shorter mean time of only 7.4 months. These participants were more intensely in love, and spent 85% or more of their waking hours thinking of their loved one.[99][11][15] This study also had participants look at a photograph of their loved one during the scan. Reward and motivation areas were active, like the VTA and areas of the caudate. Activity was also found in the insular and cingulate cortex, involved with emotion. Some interesting areas were correlated with the length of the relationship, like the ventral pallidum, implicated in attachment in prairie voles, and the anterior cingulate, implicated in obsessive thinking, cognition and emotion. This study also examined correlations with facial attractiveness to determine that the right VTA was active because of romantic passion rather than because the partner was aesthetically pleasing. Aesthetically pleasing faces elicited more activity in the left VTA, which is more associated with "liking" a reward (i.e. pleasure), whereas the right VTA is more associated with "wanting" a reward (i.e. incentive salience).[99][15] In 2011, Xu et al. repeated the experiment by Aron et al., but using Chinese participants.[128]

Ortigue et al. used fMRI to investigate the subliminal influence of romantic love on motivation, interested in how these implicit neural representations might differ from previous experiments where subjects were consciously aware of the stimulus (viewing a photograph).[129] In Ortique et al.'s study, participants were shown a subliminal prime word for 26ms (either their beloved's name, the name of a friend, or a word describing a personal passion like a hobby), followed by a series of symbols (#) for 150ms, followed by a target word for 26ms. This target was either an English word, non-word or blank, and participants were asked to identify whether it was a word or not. In trials with the love prime or passion prime, participants were faster to identify whether the target was a word or not, and this also correlated with scores on the Passionate Love Scale. The authors believe this shows that love priming activates motivation systems in the brain, rather than just evoking a particular emotion.[129] The fMRI scanning showed brain regions active for love primes similar to previous experiments, including reward and motivation areas like the VTA and caudate, but with some additions. Subliminal love priming additionally activated the bilateral fusiform gyri and angular gyri, involved in integrating abstract representations. The authors relate this to the self-expansion model of interpersonal relationships, where self-expansion by integrating the characteristics of one's beloved into one's self (called inclusion of the other in the self) is a rewarding experience which may promote romantic love feelings.[129][21]

In brain scans of long-term intense romantic love (involving subjects who professed to be "madly" in love, but were together with their partner 10 years or more) led by Bianca Acevedo, attraction similar to early-stage romantic love was associated with dopamine reward center activity ("wanting"), but long-term attachment was associated with the globus palludus, a site for opiate receptors identified as a hedonic hotspot ("liking"). Long-term romantic lovers also showed lower levels of obsession compared to those in the early stage.[21][20]

Some brain scan experiments of early-stage romantic love have found activation of the posterior cingulate cortex, which is implicated in autobiographical memory of socially relevant stimuli (e.g. partner names) and attention.[121] Most experiments (including long-term romantic love) have shown activity in the hippocampus and parahippocampal gyrus, areas involved with learning and memory.[121][21]

| Authors | Year | Type | Description | Time in love/in relationship | Stimuli |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bartels & Zeki[72] | 2000 | fMRI | Passionate love in relationships | 2.4 years (mean) | Pictures |

| Najib et al.[130] | 2004 | fMRI | Grief after rejection | Within 6 weeks after separation, after relationship at least 6 months | Rumination |

| Aron et al.[99] | 2005 | fMRI | Early-stage intense passionate love in relationships | 7.4 months (mean) | Pictures |

| Ortigue et al.[129] | 2007 | fMRI | Passionate love in relationships | 15.3 months (mean) | Names |

| Kim et al.[131] | 2009 | fMRI | Passionate love in relationships, retested 180 days later | Not more than 100 days | Pictures |

| Fisher et al.[111] | 2010 | fMRI | Intense passionate love after rejection | 63 days post-rejection, after 21 month relationship (averages) | Pictures |

| Younger et al.[25] | 2010 | fMRI | Early-stage intense passionate love in relationships, with pain reduction measure | <9 months in relationship | Pictures |

| Zeki & Romaya[132] | 2010 | fMRI | Passionate love in heterosexual and homosexual relationships | 3.7 years (mean) | Pictures |

| Acevedo et al.[21] | 2011 | fMRI | Long-term intense passionate love | Married 10–29 years | Pictures |

| Stoessel et al.[133] | 2011 | fMRI | Passionate love in happy relationships, and unhappy after separation | Maximum 6 months | Pictures |

| Xu et al.[128] | 2011 | fMRI | Early-stage intense passionate love in relationships (Chinese) | 6.54 months (mean) | Pictures |

| Xu et al.[134] | 2012 | fMRI | Intense passionate love in relationships (Chinese men who are smokers) | 14.22 months (mean) | Pictures |

| Acevedo et al.[135] | 2012 | fMRI | Marital satisfaction in long-term passionate love relationships | Married 21.4 years (mean) | Pictures |

| Poore et al.[79] | 2012 | fMRI | Reward prediction error in long-term relationships | 53 months (mean) in relationship | Gain/Loss |

| Song et al.[136] | 2015 | fMRI | Resting-state comparison of in-love with those in recently-ended relationships and those never in love | 12 months in love vs. 10 months post-breakup after 15 months in relationship (means) | Rest |

| Takahashi et al.[122] | 2015 | PET | Early-stage passionate love in relationships | 17 months (median) | Pictures |

See also

- Attachment theory – Psychological ethological theory

- Biology and sexual orientation – Field of sexual orientation research

- Interpersonal attraction – Study of the attraction between people that leads to friendship or romance

- Neuroanatomy of intimacy – Components and neurological implications of intimacy

- Passionate and companionate love – Two fundamental ways to experience romantic feelings for another person

- Religious views on love

- Reward theory of attraction

- Romance (love) – Type of love that focuses on feelings

- Theories of love – Psychological and sociological theories

References

- ^ a b c Bode, Adam; Kavanagh, Phillip S. (November 2023). "Romantic Love and Behavioral Activation System Sensitivity to a Loved One". Behavioral Sciences. 13 (11): 921. doi:10.3390/bs13110921. ISSN 2076-328X. PMC 10669312. PMID 37998668.

- ^ a b Bode, Adam; Kowal, Marta (2023). "Toward consistent reporting of sample characteristics in studies investigating the biological mechanisms of romantic love". Frontiers in Psychology. 14. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.983419. ISSN 1664-1078. PMC 10192910. PMID 37213378.

- ^ a b Tallis 2004, pp. 87–88, 106: "The cultural history of 'romance' and various meanings of the word 'romantic' make it extremely difficult to define 'romantic love'. Academic psychology—usually quite pedantic about its terminology—has been unable to establish a consensus. Some psychologists use the term in accordance with its courtly origins, whereas others use it interchangeably with 'passionate love'. As a culture, we seem to have settled on the latter usage, viewing 'romantic love' and 'falling in love' as much the same thing."

- ^ Karandashev 2017, p. xi-xiii, 35-38

- ^ Karandashev 2017, p. 7

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Bode, Adam; Kushnick, Geoff (2021). "Proximate and Ultimate Perspectives on Romantic Love". Frontiers in Psychology. 12: 573123. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.573123. ISSN 1664-1078. PMC 8074860. PMID 33912094.

- ^ a b c d e f Fisher, Helen; Aron, Arthur; Brown, Lucy (13 November 2006). "Romantic love: a mammalian brain system for mate choice". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 361 (1476): 2173–2186. doi:10.1098/rstb.2006.1938. PMC 1764845. PMID 17118931.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag Bode, Adam (16 October 2023). "Romantic love evolved by co-opting mother-infant bonding". Frontiers in Psychology. 14. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1176067. PMC 10616966. PMID 37915523.

- ^ a b c d e f Langeslag, Sandra (2024). "Refuting Six Misconceptions about Romantic Love". Behavioral Sciences. 14 (5): 383. doi:10.3390/bs14050383. PMC 11117554. PMID 38785874.

- ^ a b c Bringle, Robert G.; Winnick, Terri; Rydell, Robert J. (1 April 2013). "The Prevalence and Nature of Unrequited Love". SAGE Open. 3 (2). doi:10.1177/2158244013492160. hdl:1805/15150. ISSN 2158-2440.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Fisher, Helen E.; Aron, Arthur; Mashek, Debra; Li, Haifang; Brown, Lucy L. (1 October 2002). "Defining the Brain Systems of Lust, Romantic Attraction, and Attachment". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 31 (5): 413–419. doi:10.1023/A:1019888024255. ISSN 1573-2800.

- ^ Tallis 2004, pp. 121–132

- ^ a b Zsok, Florian; Haucke, Matthias; De Wit, Cornelia Y.; Barelds, Dick P. H. (2017). "What kind of love is love at first sight? An empirical investigation". Personal Relationships. 24 (4): 869–885. doi:10.1111/pere.12218. ISSN 1350-4126.

- ^ a b c Berscheid, Ellen (2010). "Love in the Fourth Dimension". Annual Review of Psychology. 61: 1–25. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100318. PMID 19575626.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Fisher, Helen; Xu, Xiaomeng; Aron, Arthur; Brown, Lucy (9 May 2016). "Intense, Passionate, Romantic Love: A Natural Addiction? How the Fields That Investigate Romance and Substance Abuse Can Inform Each Other". Frontiers in Psychology. 7: 687. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00687. PMC 4861725. PMID 27242601.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Fisher, Helen (March 1998). "Lust, attraction, and attachment in mammalian reproduction". Human Nature. 9 (1): 23–52. doi:10.1007/s12110-998-1010-5. PMID 26197356. Retrieved 18 February 2024.

- ^ Hendrick & Hendrick 2006, pp. 162–163

- ^ a b c d e Diamond, Lisa (January 2003). "What does sexual orientation orient? A biobehavioral model distinguishing romantic love and sexual desire". Psychological Review. 110 (1): 173–92. doi:10.1037/0033-295x.110.1.173. PMID 12529061.

- ^ a b Bode, Adam; Kavanagh, Phillip S. (1 June 2025). "Variation exists in the expression of romantic love: A cluster analytic study of young adults experiencing romantic love". Personality and Individual Differences. 239: 113108. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2025.113108. ISSN 0191-8869.

- ^ a b c Acevedo, Bianca; Aron, Arthur (1 March 2009). "Does a Long-Term Relationship Kill Romantic Love?". Review of General Psychology. 13 (1): 59–65. doi:10.1037/a0014226.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Acevedo, Bianca; Aron, Arthur; Fisher, Helen; Brown, Lucy (5 January 2011). "Neural correlates of long-term intense romantic love". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 7 (2): 145–159. doi:10.1093/scan/nsq092. PMC 3277362. PMID 21208991.

- ^ Fisher, Helen (23 January 2014). "10 facts about infidelity". TED.com. Archived from the original on 6 January 2025. Retrieved 15 January 2025.

- ^ Diamond, Lisa M. (2004). "Emerging Perspectives on Distinctions Between Romantic Love and Sexual Desire". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 13 (3): 116–119. doi:10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.00287.x. ISSN 0963-7214.

- ^ Bode, Adam; Kowal, Marta; Cannas Aghedu, Fabio; Kavanagh, Phillip S. (15 April 2025). "SSRI use is not associated with the intensity of romantic love, obsessive thinking about a loved one, commitment, or sexual frequency in a sample of young adults experiencing romantic love". Journal of Affective Disorders. 375: 472–477. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2025.01.103. PMID 39848471.

- ^ a b c d e Younger, Jarred; Aron, Arthur; Parke, Sara; Chatterjee, Neil; Mackey, Sean (13 October 2010). Brezina, Vladimir (ed.). "Viewing Pictures of a Romantic Partner Reduces Experimental Pain: Involvement of Neural Reward Systems". PLOS ONE. 5 (10): e13309. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...513309Y. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013309. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 2954158. PMID 20967200.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Machin, A.J.; Dunbar, R.I.M (2011). "The brain opioid theory of social attachment: a review of the evidence". Behaviour. 148 (9–10): 985–1025. doi:10.1163/000579511X596624. ISSN 0005-7959.

- ^ Pinker 2005, pp. xi–xii, xiv–xv

- ^ Campbell & Ellis 2005, pp. 419–423

- ^ a b c Buss 2006, p. 66

- ^ a b c d e Fletcher, Garth J. O.; Simpson, Jeffry A.; Campbell, Lorne; Overall, Nickola C. (14 January 2015). "Pair-Bonding, Romantic Love, and Evolution: The Curious Case of Homo sapiens". Perspectives on Psychological Science. 10 (1): 20–36. doi:10.1177/1745691614561683. ISSN 1745-6916.

- ^ a b Buss 2006, pp. 70–72

- ^ Kowal, Marta; Bode, Adam; Koszałkowska, Karolina; Roberts, S. Craig; Gjoneska, Biljana; Frederick, David; Studzinska, Anna; Dubrov, Dmitrii; Grigoryev, Dmitry; Aavik, Toivo; Prokop, Pavol; Grano, Caterina; Çetinkaya, Hakan; Duyar, Derya Atamtürk; Baiocco, Roberto (27 December 2024). "Love as a Commitment Device: Evidence from a Cross-Cultural Study across 90 Countries". Human Nature. 35 (4): 430–450. doi:10.1007/s12110-024-09482-6. ISSN 1045-6767. PMC 11836147.

- ^ Gelbart, Benjamin; Walter, Kathryn V.; Conroy-Beam, Daniel; Estorque, Casey; Buss, David M.; Asao, Kelly; Sorokowska, Agnieszka; Sorokowski, Piotr; Aavik, Toivo; Akello, Grace; Alhabahba, Mohammad Madallh; Alm, Charlotte; Amjad, Naumana; Anjum, Afifa; Atama, Chiemezie S. (March 2025). "The function of love: A signaling-to-alternatives account of the commitment device hypothesis". Evolution and Human Behavior. 46 (2): 106672. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2025.106672.

- ^ Buss 2006, p. 71

- ^ Campbell & Ellis 2005, pp. 420–421

- ^ Campbell & Ellis 2005, p. 422

- ^ Tallis 2004, pp. 60–66, 85–86

- ^ Tallis 2004, pp. 266–272

- ^ Campbell & Ellis 2005, p. 421

- ^ Buss 2006, pp. 73–74

- ^ Tallis 2004, pp. 201, 209–211

- ^ Fisher 2016, pp. 120–121

- ^ Wayman, Erin. "Becoming Human: The Evolution of Walking Upright". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on 26 July 2025. Retrieved 26 July 2025.

- ^ Fisher 2016, pp. 132–134

- ^ Fisher 2016, pp. 236–237

- ^ Campbell & Ellis 2005, p. 420

- ^ Fisher 2009, pp. 11, 37, 142–143, 157–159, 284

- ^ Fisher 2016, pp. 20–23, 26–27

- ^ Fisher, Helen (2012). "We have chemistry! The role of four primary temperament dimensions in mate choice and partner compatibility". The Psychotherapist. No. 52. United Kingdom: United Kingdom Council for Psychotherapy. ISSN 2049-4912.: "Passionate love, obsessive love, being in love, whatever you wish to call it. [...] In short, Explorers preferentially sought Explorers, Builders sought other Builders, and Directors and Negotiators were drawn to one another."

- ^ a b c McLennan, Deborah A. (24 June 2008). "The Concept of Co-option: Why Evolution Often Looks Miraculous". Evolution: Education and Outreach. 1 (3): 247–258. doi:10.1007/s12052-008-0053-8. hdl:1807/87202. ISSN 1936-6434.

- ^ Hazan, Cindy; Shaver, Phillip (April 1987). "Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 52 (3): 511–524. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.52.3.511. PMID 3572722. Retrieved 23 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d Leckman, James; Mayes, Linda (July 1999). "Preoccupations and Behaviors Associated with Romantic and Parental Love: Perspectives on the Origin of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder". Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 8 (3): 635–665. doi:10.1016/S1056-4993(18)30172-X. PMID 10442234.

- ^ a b c Bartels, Andreas; Zeki, Semir (March 2004). "The neural correlates of maternal and romantic love". NeuroImage. 21 (3): 1155–1166. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.11.003. PMID 15006682. Retrieved 22 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Shih, Hsuan-Chu; Kuo, Mu-En; Wu, Changwei; Chao, Yi-Ping; Huang, Hsu-Wen; Huang, Chih-Mao (26 June 2022). "The Neurobiological Basis of Love: A Meta-Analysis of Human Functional Neuroimaging Studies of Maternal and Passionate Love". Brain Sciences. 12 (7): 830. doi:10.3390/brainsci12070830. ISSN 2076-3425. PMC 9313376. PMID 35884637.

- ^ Ortigue, Stephanie; Bianchi-Demicheli, Francesco; Patel, Nisa; Frum, Chris; Lewis, James W. (1 November 2010). "Neuroimaging of Love: fMRI Meta-Analysis Evidence toward New Perspectives in Sexual Medicine". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 7 (11): 3541–3552. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01999.x. ISSN 1743-6109.

- ^ a b Diamond, Lisa M. (2004). "Emerging Perspectives on Distinctions Between Romantic Love and Sexual Desire". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 13 (3): 116–119. doi:10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.00287.x. ISSN 0963-7214.

- ^ Tennov 1999, pp. 24, 216

- ^ Hayes, Nicky (2000), Foundations of Psychology (3rd ed.), London: Thomson Learning, pp. 457–458, ISBN 1861525893: "Tennov (1979) used the term limerence to refer to a kind of infatuated, all-absorbing passion — the kind of love that Dante felt for Beatrice, or that Juliet and Romeo felt for each other. Tennov argued that an important feature of limerence is that it should be unrequited, or at least unfulfilled. It consists of a state of intense longing for the other person, in which the individual becomes more or less obsessed by that person and spends much of their time fantasising about them. [...] Tennov suggests that limerence can only really last if external conditions are such that it remains unfulfilled: it is not uncommon for people to maintain a state of limerence about someone who is unreachable for some years; but if the desired person should actually come within reach, so that the desired relationship begins, then the limerence becomes extinguished and the attraction sometimes disappears very quickly."

- ^ Beam 2013, pp. 72, 75: "[Tennov] discovered that many who considered themselves 'madly in love' had similar descriptions of their emotions and actions. She chose the label limerence to describe an intense longing and desire for another person that is much stronger than a simple infatuation, but not the same as a long-lived love that could last a life-time. [...] In 2002, Helen Fisher, PhD, in concert with other researchers, published the article 'Defining the Brain Systems of Lust, Romantic Attraction, and Attachment' in the Archives of Sexual Behavior. Considered a leading researcher [...], she and her research colleagues have identified several characteristics of a person who is 'madly in love,' or, as we put it, in limerence."

- ^ a b Tallis 2004, pp. 216–218, 235: "There are certainly some striking similarities between love and addiction[.] [...] At first, addiction is maintained by pleasure, but the intensity of this pleasure gradually diminishes and the addiction is then maintained by the avoidance of pain. [...] The 'addiction' is to a person, or an experience, not a chemical. [...] [O]ne of the characteristics shared by addicts and lovers is that they both obsess. The addict is always preoccupied by the next 'fix' or 'hit', while the lover is always preoccupied by the beloved. Such obsessions are associated with compulsive urges to seek out what is desired [...]."

- ^ Grant, Jon; Potenza, Marc; Weinstein, Aviv; Gorelick, David (21 June 2010). "Introduction to Behavioral Addictions". The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 36 (5): 233–241. doi:10.3109/00952990.2010.491884. PMC 3164585. PMID 20560821.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Zou, Zhiling; Song, Hongwen; Zhang, Yuting; Zhang, Xiaochu (21 September 2016). "Romantic Love vs. Drug Addiction May Inspire a New Treatment for Addiction". Frontiers in Psychology. 7: 1436. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01436. PMC 5031705. PMID 27713720.

- ^ a b c d Koob, George F; Volkow, Nora D (August 2016). "Neurobiology of addiction: a neurocircuitry analysis". The Lancet Psychiatry. 3 (8): 760–773. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(16)00104-8. PMC 6135092. PMID 27475769.

- ^ a b c d e f Berridge, Kent; Robinson, Terry (2016). "Liking, wanting, and the incentive-sensitization theory of addiction". American Psychologist. 71 (8): 670–679. doi:10.1037/amp0000059. PMC 5171207. PMID 27977239.

- ^ a b c d Berridge, Kent; Robinson, Terry; Aldridge, J. Wayne (February 2009). "Dissecting components of reward: 'liking', 'wanting', and learning". Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 9 (1): 65–73. doi:10.1016/j.coph.2008.12.014. PMC 2756052. PMID 19162544.

- ^ a b c d Robinson, Terry E.; Berridge, Kent C. (17 January 2025). "The Incentive-Sensitization Theory of Addiction 30 Years On". Annual Review of Psychology. 76: 29–58. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-011624-024031. ISSN 0066-4308. PMC 11773642.

- ^ Baskerville, Tracey A.; Douglas, Alison J. (6 May 2010). "Dopamine and Oxytocin Interactions Underlying Behaviors: Potential Contributions to Behavioral Disorders". CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics. 16 (3). doi:10.1111/j.1755-5949.2010.00154.x. ISSN 1755-5930. PMC 6493805. PMID 20557568.

- ^ a b Olney, Jeffrey J; Warlow, Shelley M; Naffziger, Erin E; Berridge, Kent C (August 2018). "Current perspectives on incentive salience and applications to clinical disorders". Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences. 22: 59–69. doi:10.1016/j.cobeha.2018.01.007. PMC 5831552. PMID 29503841.

- ^ Nestler, Hyman & Malenka 2010, p. 147-148, 266, 364-367, 376: "Most [neurons which produce dopamine] have their cell bodies in two contiguous regions of the midbrain, the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) and the ventral tegmental area (VTA). [...] Neurons from the VTA innervate the ventral striatum (nucleus accumbens), olfactory bulb, amygdala, hippocampus, orbital and medial prefrontal cortex, and cingulate cortex. [...] [D]opamine confers motivational salience ("wanting") on the reward itself or associated cues (nucleus accumbens shell region), updates the value placed on different goals in light of this new experience (orbital prefrontal cortex), helps consolidate multiple forms of memory (amygdala and hippocampus), and encodes new motor programs that will facilitate obtaining this reward in the future (nucleus accumbens core region and dorsal striatum). [...] Dopamine acts in the nucleus accumbens to attach motivational significance to stimuli associated with rewards (such as food). [...] The brain reward circuitry targeted by addictive drugs [...] includes the dopaminergic projections from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) of the mid-brain to the nucleus accumbens (NAc) and other forebrain structures. [...] A reward is a stimulus that the brain interprets as intrinsically positive or as something to be approached. A reinforcing stimulus is one that increases the probability that behaviors paired with it will be repeated. [...] The neural substrates that underlie the perception of reward and the phenomenon of positive reinforcement are a set of interconnected forebrain structures called brain reward pathways; these include the nucleus accumbens (NAc; the major component of the ventral striatum), the basal forebrain (components of which have been termed the extended amygdala [...]), hippocampus, hypothalamus, and frontal regions of cerebral cortex. These structures receive rich dopaminergic innervation from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) of the midbrain."

- ^ a b c d Aron, Arthur; Fisher, Helen; Mashek, Debra J.; Strong, Greg; Li, Haifang; Brown, Lucy L. (July 2005). "Reward, Motivation, and Emotion Systems Associated With Early-Stage Intense Romantic Love". Journal of Neurophysiology. 94 (1): 327–337. doi:10.1152/jn.00838.2004. ISSN 0022-3077. PMID 15928068. S2CID 396612.

- ^ Aron, Fisher & Strong 2006, p. 601

- ^ a b c Bartels, Andreas; Zeki, Semir (27 November 2000). "The Neural Basis of Romantic Love". NeuroReport. 11 (17). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: 3829–3834. doi:10.1097/00001756-200011270-00046. PMID 11117499. S2CID 1448875.

- ^ Hatfield & Walster 1985, pp. 103–105

- ^ a b Schultz, Wolfram (31 March 2016). "Dopamine reward prediction error coding". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 18 (1): 23–32. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2016.18.1/wschultz. PMC 4826767. PMID 27069377.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Love, Tiffany M. (April 2014). "Oxytocin, motivation and the role of dopamine". Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 119: 49–60. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2013.06.011. PMC 3877159.

- ^ Berridge, Kent C. (1 April 2007). "The debate over dopamine's role in reward: the case for incentive salience". Psychopharmacology. 191 (3): 391–431. doi:10.1007/s00213-006-0578-x. ISSN 1432-2072.

- ^ a b Diederen, Kelly M. J.; Fletcher, Paul C. (2021). "Dopamine, Prediction Error and Beyond". The Neuroscientist. 27 (1): 30–46. doi:10.1177/1073858420907591. ISSN 1073-8584. PMC 7804370.

- ^ Watabe-Uchida, Mitsuko; Eshel, Neir; Uchida, Naoshige (25 July 2017). "Neural Circuitry of Reward Prediction Error". Annual Review of Neuroscience. 40: 373–394. doi:10.1146/annurev-neuro-072116-031109. ISSN 0147-006X. PMC 6721851.

- ^ a b Poore, Joshua; Pfeifer, Jennifer; Berkman, Elliot; Inagaki, Tristen; Welborn, Benjamin Locke; Lieberman, Matthew (8 August 2012). "Prediction-error in the context of real social relationships modulates reward system activity". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 6. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2012.00218. ISSN 1662-5161. PMC 3413956.

- ^ a b c Earp, Brian D.; Wudarczyk, Olga A.; Foddy, Bennett; Savulescu, Julian (2017). "Addicted to Love: What Is Love Addiction and When Should It Be Treated?". Philosophy, Psychiatry, & Psychology. 24 (1): 77–92. doi:10.1353/ppp.2017.0011. ISSN 1086-3303. PMC 5378292. PMID 28381923.

- ^ Costa, Sebastiano; Barberis, Nadia; Griffiths, Mark D.; Benedetto, Loredana; Ingrassia, Massimo (1 June 2021). "The Love Addiction Inventory: Preliminary Findings of the Development Process and Psychometric Characteristics". International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 19 (3): 651–668. doi:10.1007/s11469-019-00097-y. ISSN 1557-1882.

- ^ Bolshakova, Maria; Fisher, Helen; Aubin, Henri-Jean; Sussman, Steve (31 August 2020), Sussman, Steve (ed.), "Passionate Love Addiction: An Evolutionary Survival Mechanism That Can Go Terribly Wrong", The Cambridge Handbook of Substance and Behavioral Addictions (1 ed.), Cambridge University Press, pp. 262–270, doi:10.1017/9781108632591.026, ISBN 978-1-108-63259-1, retrieved 12 June 2025