Białystok during World War II

Białystok during World War II endured two occupations and suffered extensive human and physical devastation The war broke in September 1939, when Nazi Germany invaded Poland on 1st of September followed by the Soviet Union on the 17th of September. At that time, Białystok was the capital of Białystok Voivodeship in the Second Polish Republic. The city changed hands several times during the war. Initially occupied by German forces in early September 1939, it was soon transferred to Soviet control when the Red Army entered on September 20, in line with the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. The city, together with the surrounding territories was then annexed to the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic and it became the capital of Belastok Region.[1] During this period it passed through a massive Sovietization process which included installation of Soviet political system, nationalization of the economic sectors and adaptations of Soviet economic models, tight censorship and deportations to the Soviet Union. On June 1941, during Operation Barbarossa, the city was occupied again by the German Army and it became the capital of Bialystok District.[1] The German occupation further continued severe repression and exploitation, culminating in the establishment of the Białystok Ghetto. Following a failed uprising in August 1943, the remaining Jewish population was deported to the Treblinka extermination camp. German repression and exploitation of the city continued but by 1944, following a series of losses in major battles, the front came closer to the city, when in July 1944, shortly before they retreated, the Germans set in fire large part of the city center. On July 27, 1944 the Soviets entered the city. While in the first days of the renewed Soviet occupation, it was uncertain whether the city would become part of Poland or the Soviet Union by the end of August it was decided by the Soviet Union to hand over the city to Poland. By the time the war ended in May 1945 Białystok had undergone a dramatic transformation with 80% of the city's buildings destroyed (especially in the city center), its industrial potential fell by 74%, its once thriving large jewish community vanished and the overall population fell from approximately 100,000 in 1938 to fewer than 50,000.[2][3][4]

Background

At the turn of March and April 1939, Białystok intensified preparations to protect its population from potential bombings and gas attacks. Citizens received training in self-defense, while plans for trenches and shelters were developed. Specialized services were established, including alarm, communications, fire, rescue-medical, and technical units. Alongside scouts, various organizations contributed to these efforts, such as the Airborne and Antigas Defence League, the Polish Red Cross, the Polish Western Union, the Union of Reserve Officers of Poland and the Riflemen's Association.[5] The local newspaper Echo Białostockie provided instructions on how to respond during an air raid. In late July, a large-scale project began to dig anti-aircraft trenches across the city, particularly in the downtown area, near the two railway stations and the military barracks. Citizens also supported national defense initiatives by contributing to arms purchases for the Polish Army.[6] For instance, employees of the Plywood State Factory in Dojlidy, employing over 400 people, bought a heavy machine gun for the Polish Armed Forces. funded the purchase of a heavy machine gun for the armed forces. Additionally, money was raised for the National Defense Fund and the Maritime Defense Fund. On the eve of war, tensions increased due to a surge in espionage and sabotage, straining relations with the local German community. As a result, public gatherings among the German population were banned starting May 13.[7]

On August 27, just days before the war broke out, the Citizens' Committee for the Defence of the Homeland was formed.[8] Led by local parson Aleksander Chodyko, the committee included representatives from the Camp of National Unity, the Polish Socialist Party, and the Polish People's Party. The committee was divided into sections: one assisted the families of reservists, another supported soldiers, and a third handled propaganda efforts via newspapers and loudspeakers installed on town halls, the NCO military officers' club on Sienkiewicza Street, the balcony of the Municipal Library, and other key locations. Two additional sections were assigned to help with provisioning and shelter construction.[9]

On August 31, Military field Hospital No. 303[10] was opened in the Teachers' Seminary next to Branicki Palace on Mickiewicza Street.[11][12] The hospital had 300 beds and was staffed by 11 military doctors. As the number of wounded increased, additional patients were moved to the Princess Anna Jabłonowska High School.

Onset of the war

On 1 September 1939, the Germay invaded Poland marking the start of World War II. German bomber squadrons flew over Białystok Voivodeship, dropping the first bombs on military barracks and near the Białystok railway station, killing a woman near Wronia Street.[13] From September 4, the Citizen Guard (Polish: Straż Obywatelska), established by the city president Seweryn Nowakowski, was operating in the city, tasked with supporting and replacement functions for the police and the army which were evacuated.[14] The local press reported on the successes of the Polish Forces and even the air raids of Polish Air Force on Berlin. Only the information about the entry into East Prussia of cavalry squadrons supported by horse artillery proved to be true. The frontline around Białystok remained relatively calm, with skirmishes mainly around Myszyniec and Grajewo.

Białystok’s air raid alarm system functioned efficiently. Coloured shields were displayed on the tower of St. Roch Church to signal alarms, and factory sirens and gongs were used throughout the city. The Municipal Citizens' Committee for Social Self-Help with several sections began its work, and the Palace Theatre became the Polish Soldier's House. From September 4, the Civil Guard (Polish: Straż Obywatelska), established by city president Seweryn Nowakowski, was operating in the city, tasked with supporting and replacement functions for the state police and the army which were evacuated.[14] Some conscripts were sent to patrol the city to deter looting and enforce order, punishing shopkeepers who inflated prices. When the war broke, voivode of Białystok Voivodeship, Henryk Ostaszewski, ordered partial evacuation of state offices and institutions from Białystok. After September 11, the Citizens' Guard fully assumed the duties of the evacuated State Police. On the night of September 10–11, many officials, including Ostaszewski, left the city, and selected archives were taken with them.[15]

According to the Polish defense plans, Białystok was not intended for defense, and the military units located in the city took positions far from their garrison.[16] The following units remained in the city: the marching battalion of the 42nd Infantry Regiment, the marching squadrons of the Podlaska Cavalry Brigade and Suwałki Cavalry Brigade, the marching platoon of the 14th Horse Artillery Divizion at the barracks in Bema street with two cannons, guard unit no. 32, machine gun company no. 38 and anti-aircraft battery no. 5. Around September 10, the Wołkowysk Reserve Cavalry Brigade began forming, incorporating the cavalry squadrons. The infantry units, no longer in contact with their parent regiments, were still quartered in the barracks.

However, reports from the Narew River prompted a decision to resist:[17] Lieutenant Colonel Zygmunt Szafrankowski (commander of the District Command of Supplements and at the same time the oldest rank officer in Białystok) and Captain Tadeusz Kosiński (chief of staff) decided to mount a defense using marching and reserve units along with retreating soldiers from Narew..[18] They had at their disposal primarily the marching battalion of the 42nd Infantry Regiment and the incomplete guard battalion No. 33. Other sub-units were added, Infantry arrived from near Wizna were gathered as well as two squadrons of the 2nd Grochow Uhlan Regiment from Suwałki.

The defensive line created by the assembled units stretched from Dojlidy and Nowe Miasto, through Wysoki Stoczek, to Pietraszi: Uhlans from two squadrons of the 2nd Regiment were placed in Białostoczek and Pietrasze, guard battalion No. 32 was deployed in Nowe Miasto, and the center of defense was the hills of Wysokie Stoczek manned by the marching battalion of the 42nd Infantry Regiment commanded by Lieutenant Ignacy Stachowiak and chief of staff Antoni Malecki.[19] In addition, the city's defenders were supported by a company of heavy machine guns and one artillery platoon In total, the Polish defense force numbered about 900 soldiers.[20]

On September 11, Military field hospital no. 303 was evacuated[21][22] by train and the most seriously injured, approximately two hundred people, were transferred to civilian hospitals.[23] Combat contact between German and Polish units defending the Narew River crossing near Żółtki established on September 13. The defense command took up a position near the city slaughterhouse, at the intersection of Hetmańska and Żółtkowska Streets. On the evening of September 14th, the bridge over the Biała River in Bacieczki was blown up.

On the morning of September 15, German forces launched multiple assaults on the central section of the Polish positions in the area of the Marczuk and Wysoki Stoczek districts in several waves. The Polish forces were ordered to fight until 12:00. On 14:00. Polish troops were ordered to hold their ground until noon. After hours of intense fighting and repelling four waves of attacks, the two squadrons of the 2nd Grochow Uhlan Regiment, then the 42nd Regiment companies retreated towards the area of the train station and St. Roch's Church, where they assembled and then left through Piłsudskiego, Rynek Kościuszki, Kilińskiego, Żwirki i Wigury streets further (some units not before late evening) to the east towards Wołkowysk (following the war it was transferred to Byelorussian SSR).[24][20][25] while other units headed towards Zielona and from there in the direction of Vilnius.[19] Captain Kosiński seriously wounded in the battles and died later that day in a hospital in Warszawska street.[26] Overall, the number of Polish casualties is estimated at several dozens, and from September 1st to 16th, approximately 100 soldiers who died in local hospitals were buried at the Military Cemetery in Zwierzyniecki Forest.[27]

On 15 September, Białystok was occupied by the "Lötzen" Fortress Brigade under General Otto-Ernst Ottenbacher.[28] The Germans limited themselves to establishing the Military City Command, which ordered the surrender of all weapons and ammunition and the disbandment of the Citizens' Guard. A curfew and various restrictions were introduced. However, no civil administration was created, because these areas were to be occupied by the Soviets. Within a few days, a dozen or so Jewish residents were murdered. A transit camp for prisoners of war was set up in Primary School No. 1. On September 20, Wehrmacht soldiers executed eight people in the school’s courtyard for "disobedience".[15] Between September 20 and 21, Einsatzgruppe IV arrived in Białystok and began carrying out atrocities against the civilian population.[29]

Soviet occupation

.jpg)

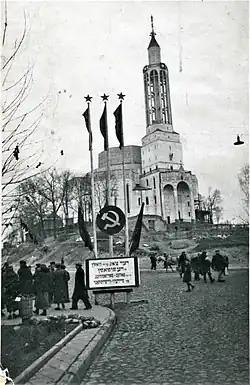

From 20 to 22 September, negotiations took place at the Branicki Palace regarding the transfer of the city from German to Soviet control. According to the agreement, the Wehrmacht was to withdraw by 14:00 on 22 September. After the talks concluded, both delegations attended a dinner at the Ritz Hotel. On 22 September, a formal handover ceremony was held in the courtyard of the Branicki Palace. It was attended by Ivan Boldin, commander of the Cavalry-Mechanized Group in the Byelorussian Military District and Andrey Yeremenko, commander of the 6th Cavalry Corps. A group of 120 Soviet soldiers from the 6th Cavalry Corps was permitted by the Germans to enter the city and take part in the ceremony. A brief joint parade took place along Lipowa Street and Kościuszko Market Square with Soviet and German vehicles driving in opposite directions,[30] and then the Germans handed over power to the Soviets and withdrew.[31][32] The ceremony concluded with the official transfer of authority to the Soviets, in accordance with the secret protocol of the Molotov–Ribbentrop pact and the Germans withdrew.[33]

The NKVD soon established its office in Białystok, occupying the building of the District Court at 5 Mieczkiewica Street.[34][35] The first chief of the provincial NKVD was Alexander Misiuriev who was later replaced by Peter Gladkov and Sergei Bielchenko. Among the victims of the arrests wave were employees of the District Court who were arrested such as Józef Ostruszka, the last president of the court (he was imprisoned in Białystok, then expelled with others to Soviet camps), Vice President Karol Wolisz,[36] Jan Bolesław Stokowski who chief secretary of the regional court and head of the Tax office.[37] The People's Assembly of Białystok met on 28–30 October at the Municipal Theatre under the slogan: "death to the white eagle".[38] The NKVD also took over the local prison.[39] In October, the NKVD arrested pre-war Polish mayor Seweryn Nowakowski, who was then probably deported to the USSR, however his fate remains unknown.[40] Białystok native and future President of Poland in exile Ryszard Kaczorowski was a member of the local Polish resistance and was arrested in the city by the NKVD in 1940.[41] Initially sentenced to death, he was later given 10 years in forced labor camps and deported to Kolyma. He was released in 1942 and joined Anders' Army.[41]

On 22 October 1939, less than two weeks after the Soviet invasion, the occupation authorities organized elections into a National assembly of West Belarus (Belarusian: Народны сход Заходняй Беларусі). The official turnout was 96.7 percent, with 90 percent of the vote going to candidates backed by the Soviet Union. The Elections to the People's Assemblies of Western Ukraine and Western Belarus took place under control of NKVD and the Communist Party.[42] On 30 October the National Assembly session held in Białystok passed the decision of so-called West Belarus joining the USSR and its unification with the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic. These petitions were officially accepted by the Supreme Soviet of the USSR on 2 November and by the Supreme Soviet of the Byelorussian SSR on 12 November, thus formalizing the creation of Belastok Voblast within the Byelorussian SSR with the center in Białystok.[43]

The city was divided into three administrative districts: Dzierzynski, Molotowski and Sowiecki. The comparison between the Soviet ruble and the Polish złoty triggered a wave of consumer activity, with Soviet newcomers purchasing large quantities of goods, leading to shortages and inflated demand. Long queues, rationing, and the black market in defiance of existing prohibitions became a regular part of life. Textile factories were consolidated into larger industrial complexes (kombinaty) and a labour competition campaign was launched under the slogan: "Białystok - the second Ivanovo".

The massive presence of Soviet troops in Białystok and its surroundings[44] quickly overwhelmed existing military infrastructure. Former Polish Army barracks, all repurposed for Soviet use, proved insufficient. As a result, soldiers were quartered in confiscated palaces, estates, religious buildings, and other public facilities. Despite these efforts, the continuous arrival of new and reorganized units led to overcrowded and often primitive living conditions.[45] The 6th Armoured Brigade was stationed in the barracks on Bema Street, the cavalry and other types of troops were deployed in the barracks on Traugutta, Wołodyjowskiego and Kawaleryjska streets. In the latter, part of the storage rooms was occupied by the air force.[46] On order of the 10th Army command, the 66th Anti Aircraft Brigade was established in stationed in Krywlany Airfield and on the Dojlidy district to give the city anti aircraft protection.[47] The 10th Army headquarters was set up in the District Court building on Mickiewicza Street. The ground floor housed the headquarters’ security department as well as the editorial office and printing house of the army newspaper Za Sovetskuyu Rodinu (“For the Soviet Homeland”). The adjacent Treasury Chamber building was occupied by the NKVD’s Special Department attached to the army command. Army vehicles and service subunits were parked in the square between the buildings. Along both sides of Żwirki i Wigury Street, from the Biała River to the Market Square, a residential quarter was designated for senior officers.

In the place where the Gołębiewski Hotel is located today, there was Ksawery Branicki's tenement house, which was set up as a hotel for officers of the special department of the army command. Next door, in a wooden villa, the deputy commander of the army for political affairs, General Dmitry Dubrovsky, lived with his family.[48]

A kindergarten for children of staff officers was set up in a wooden villa with a large garden in the location of today's city hall. At 2 Mickiewicza Street, a garrison hospital was organized in what is now the Medical University building. The Polish military casino at 15 Sienkiewicza street was transformed into a casino of the Red Army. Housing shortages worsened by the summer of 1940, when additional units began arriving in the Belastok Region.[45] This often led to illegal seizures of properties and the forced eviction of residents, creating tensions with the local population.[49] The local administration, lacking authority to enforce property laws, struggled to respond, resulting in frequent disputes. With billeting facilities in short supply, field camps were rapidly expanded to accommodate incoming troops. The housing problems became even more visible with the arrival of new units to the region.[50] The limited number of allocated billeting facilities resulted in the intensive expansion of the field camps in which most of the units were stationed. The command of the 6th Mechanized Corps and part of the 1st Rifle Division were stationed in now-demolished barracks on Wołodyjowskiego Street.[51] The command of the 4th Armoured Division and some of its units, including the 4th Armored Infantry Division and units of the 10th Army were located in the barracks on Bema Street.[52][53] Former Polish Army barracks of the 10th Lithuanian Uhlan Regiment on Kawaleryjska Street were also repurposed, hosting parts of the 4th Armored Division. Airport service and security units were stationed at the Krywlany airfield. The 41st Fighter Aviation Regiment of the 9th Mixed Air Division stationed at the airfield.[54] Across Mickiewicza Street, between today's Wiewiórcza and Kuronia streets, a logistics base and military camp were set up to support airport expansion. The Nowik Palace housed the air division’s headquarters, while the communications company was stationed in the building behind it.[55]

The situation with storage facilities and repair shops was no better. The correspondence between the commanders of individual units and the Białystok city authorities shows that the military could not count on the civilian authorities’ help in this respect. The commander of the 4th Independent Signal Battalion, Captain Nikolai Karpovsky, who had been quartered since 8 August 1940 on the property at 56 Pocztowa (Jurowiecka) Street, demanded in early April 1941 that the City Council transfer to him additional storage facilities at 47 Poleska Street and 37 Fabryczna Street, and that the owner of the property at 56 Pocztowa Street be evicted.[56] The city authorities refused to accept his demands. The housing situation of the tank repair units was to be improved by a repair and overhaul base, the construction of which began in the spring of 1941 at 24 Choroszczańska street. Its construction was planned to be completed in December 1941. The situation with training facilities was similar. In a report prepared at the beginning of May 1941, General Mikhail Khatskilevich, commander of the 6th Mechanized Corps reported a lack of teaching facilities, training grounds and shooting ranges. The worst situation in this respect was in units of the 29th Motorised Division. The land designated by the local authorities for the training needs of the units was still used by the local population. Therefore, there were field, primitive shooting ranges, which were only sufficient for basic firearms training. The 8th Infantry Regiment and 4th Anti-Aircraft Artillery Divizion of the 4th Tank Division led by Andrei Potaturchev did not have any shooting ranges at all. The only fully-fledged training ground in Zielona, was not adapted to conduct shooting at moving targets.[45]

Insufficient housing resources in Białystok and the surrounding area led the Soviet authorities to built a warehouse base and temporary barracks on the site of today's municipal market on Kawaleryjska Street. The second complex was organized along both sides of the railway line running to Bielsk Podlaski, on the section from the barracks to Ignatki.[57] The soldiers living there were billeted in wooden barracks and tents. The barracks of the 42nd Infantry Regiment on Traugutta Street were occupied by units including the 1st Armored Regiment. However, this was an insufficient area and the Soviets built another warehouse and barracks complex on the Wygoda district, north of the barracks. Temporary barracks were organized for the needs of the 7th Armored Division in the area located between the railway line and Krupniki. Additionally, some of the division's units were quartered in Folwark Nowosiółki and the complex organized to the north of it. Warehouse bases were built in Starosielce, Horodniany and Księżyno.[58]

Annexation and Sovietization

Following the incorporation of Białystok and the surroundings as Belastok Region in the Byelorussian SSR, a policy of Sovietization was swiftly implemented. In 1940, the town hall and the building housing the city scales were demolished to create a large open space for rallies and demonstrations. The square was adorned with striking red propaganda posters. At 27 Sovietskaya Street (Kościuszko Market Square), the Gorky District Library replaced the former City Public Library. Semyon Igayev, previously the Second Secretary of the Mogilev Obkom, was appointed as the Secretary of Białystok’s Obkom and later succeeded by Vladimir Gaisin. The Gorkom (city council) operated from 21 Warszawska Street, a building that no longer exists. From 20 November 1939 to February 1940, Girsz Gerszman served as the First Secretary of the Party City Committee, while Paweł Sienkiewicz was appointed Chairman of the City Executive Committee. The Soviets also sanctioned the establishing of a Yiddish-language newspaper, the Der Bialistoker Shtern.[59]

After being being annexed to the Soviet Union, thousands of ethnic Poles, Belarusians and Jews, were forcibly deported to Siberia by the NKVD, which resulted in over 100,000 people deported to eastern parts of the USSR.[60][61] Among the deported Poles were civil servants, judges, police officers, professional army officers, factory owners, landlords, political activists, leaders of cultural, educational and religious organizations, and other activists in the community. All of them were dubbed enemies of the people.[62] After October 25, Białystok was cleared of the so-called biezents, mostly Jewish refugees who had fled from areas under German occupation. The first major deportation of Białystok residents took place on 10–11 February 1940, when 1,582 people were sent by rail to Taiynsha, Kazakh SSR.[63] A second wave followed on 13 April, targeting the families of prisoners of war and those already held in Soviet camps or prisons. Transports departed from the Białystok Fabryczny Railway Station to Pavlodar and Taiynsha in the Kazakh SSR. In June 1940, five additional cattle wagons trains with of deportees left the city: three to Kotlas, one to Arkhangelsk, and one to Szabalino in Kirov Oblast.[64]

The integration of Białystok into the BSSR led to a significant influx of people from the Soviet interior, along with migration from nearby towns—particularly by local Belarusians—likely in an effort to strengthen the city’s ethnic base for Soviet governance. This shift supported the institutionalization of Belarusians and Belarusian culture took place in the city on a larger scale: Among others Belarusian schools, Pedagogical Institute with the Belarusian language faculty and Belarusian theatre were set up in the city. During this period there was a change in ethnic division in the city. Poles lost their dominant significance.[65][66] As a result, the ethnic composition of Białystok began to change, and Poles lost their previously dominant position. These demographic and political changes led to increased national tensions within the city, accompanied by a growing number of restrictions and prohibitions.[67]

Street names

Following the Invasion of the Soviet Union to Poland, Białystok was annexed to the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic (BSSR) and a massive Sovietization policies implemented. As such, many streets were renamed to promote Soviet and Communist ideology and narrative. On the 8th of January 1940 the Soviet-controlled city hall (called in Polish Miejski Komitet Wykonawczy w Białymstoku) published the list of street renaming, (officially in according with demands of the working people following the Conference of the Union of the Textile, Food and Construction Industry and the Meeting of Representatives of Workers' Councils). Among the changes:[68]

| Old name | New name |

|---|---|

| Piłsudskiego | Sowiecka |

| Rynek Kościuszki | Sowiecka |

| Kilińskiego | Sowiecka |

| Sienkiewicza | Lenina |

| Wasilkowska | Lenina |

| Dąbrowskiego | Czapajewa |

| Nowy Świat | Swierdłowa |

| Giełdowa | Leningradzka |

| Sobieskiego | Marksa |

| Jurowiecka | Pocztowa |

| Piasta | Gorkiego |

| Żwirki i Wigury | Czkałowa |

| Branickiego | Szczorsa |

| Giełdowa | Leningradzka |

| Kościelna | Tołstoja |

| Jagiellońska | 8 Marca |

| Park 3 Maja | 17 Września |

| Aleja 11 Listopada | 17 Września |

| Legionowa | Lotnicza |

| Rabińska | Majakowskiego |

| Harcerska | Sportowa |

| Jerozolimska | Czerwonej Gwiazdy |

| Bożnicza | Papanińska |

| Św. Rocha | Październikowa |

| Palestyńska | Luksemburga |

| Szlachecka | Kołchoźnicza |

| Świętojańska | Kominternu |

| Hetmańska | Libknechta |

| Nowy Świat | Swierdłowa |

| Poznańskiej | Dzierżyńskiego |

| Słonimska | Kirowa |

| Stołeczna | Czajkowskiego |

| Świętokrzyska | Stalskiego |

| Ułańska | Ulianowa |

| Wersalska | Moskiewska |

| Bema | Komsomolska |

| Częstochowska | Rewolucyjna |

| Grunwaldzka | Urickiego |

| Waszyngtona | Engelska |

Resistance

The Polish resistance movement which served as one of six main command centers of the Union of Armed Struggle in occupied Poland, alongside Warsaw, Kraków, Poznań, Toruń, and Lwów.[69] Resistance efforts in the Białystok region—particularly along the swampy Biebrza River began immediately after the September Campaign. By mid-1940, underground organizations operated in 161 towns and villages across what would later become the Bezirk Bialystok.[70] Demonstrations occurred on 1 and 11 November 1939 at the Military Cemetery, and on 7 November of that year during a parade. The origins of the Service for Poland’s Victory, later transformed into the Union of Armed Struggle, trace back to late September 1939 in Białystok, when Lieutenant Colonel Franciszek Śleczka ("Kruk"), representing General Józef Olszyna-Wilczyński, arrived in the city. Białystok native and future President of Poland in exile Ryszard Kaczorowski served as liaison between the Union of Armed Struggle and the Grey Ranks, He held several leadership roles, initially as deputy district commander, then district leader from February 1940, and commander of the Chorągiew from June 1941. He was arrested by the NKVD in 1940. Although initially sentenced to death, his punishment was later commuted to 10 years in a forced labour camp and deported to Gulag camp in Kolyma. He was released in 1942 and joined Anders’ Army.[41] The scout conspiracy of the Grey Ranks was also active in the city, led by ZHP commander Gabriel Pietraszewski[71] and troop commander Marian Dakowicz.[72]

German occupation

On June 22, 1941, without any formal declaration of war, Nazi Germany launched a surprise attack on the Soviet Union. That same day, as part of the Battle of Białystok–Minsk, German bombs struck Białystok railway station, military facilities, and nearby buildings. Early that morning, the local branch of the Białystok District of the Communist Party of Byelorussia convened an emergency meeting. The result was the formation of a special commission tasked with evacuating military families, civilians, and classified documents. The head of the NKGB established two subversive and spy groups to form the foundation of Soviet partisan activity. Although Soviet authorities downplayed the German invasion, referring to it as "maneuvers", they ordered the evacuation of Białystok on June 23. .[73]

At least several dozen residents were killed in the initial bombings. On June 22, as Soviet troops retreated under German pressure, they committed atrocities against local residents.[74] Civilians encountered by withdrawing units were executed, with entire families reportedly dragged from their homes and shot.[74] Among the victims were prominent figures such as a professor from the Teachers' Seminary, painter Józef Blicharski, and priest Adolf Odziejewski.[75]

On the morning of 27 June 1941, the Wehrmacht entered to the city. Troops from Police Battalion 309 and Police Battalion 316 of the Order Police[76] surrounded the central town square by the Great Synagogue, the largest wooden synagogue in Eastern Europe, and forced residents from their homes into the street. Some were shoved up against building walls and shot dead. Others, some 800 men, women and children were locked in the synagogue, which was subsequently set on fire; there they were burned to death. The Nazi onslaught continued with the demolition of numerous homes and further shootings. As the flames from the synagogue spread and merged with the grenade fires, the entire square was engulfed. By the end of the day, approximately 3,000 Jews were killed, out of a pre-war Jewish population of around 50,000. [77] In addition to the synagogue catastrophe, a series of pogroms and mass executions committed by the Ordnungspolizei and SS against the Jewish population of Białystok took place at the turn of June and July 1941. On July 3, Einsatzgruppe B rounded up nearly a thousand Jews in Białystok. Roughly 300, mostly intellectuals, were executed in the Pietrasze Forest the following day. Further executions, directly ordered by Heinrich Himmler, occurred on July 12 and 13. During these days, members of the police battalions 316 and 322 shot approximately 4,000 Jews in the Pietrasze forest.[1]

In the aftermath of the June 1941 Battle of Białystok–Minsk Białystok was placed under German Civilian Occupation (Zivilverwaltungsgebiet) as Bezirk Bialystok. The area was under German rule from 1941 to 1944/45, without ever formally being incorporated into the German Reich. Until the end of July the city was subject to military authorities, then the Civilian Board took over power, which was headquartered at the Branicki Palace. Hitler established Bezirk Bialystok by decree of July 22, placing Erich Koch, Gauleiter and Overseas President of East Prussia, at its head. The latter set the Lubomirski Palace as his residence. Alongside the civil administration of the district and the city county (Stadtkomisariat), the city housed extensive German security and military forces, including police units, Wehrmacht reserves, airport and rail security, and intelligence services. The long-term Nazi goal was to incorporate Bezirk Bialystok into East Prussia and fully Germanize the region.

Shortly after the German occupation began, the German authorities established the Białystok Ghetto, a Nazi ghetto set up by the German SS between July 26 and early August 1941 in the newly formed District of Bialystok within occupied Poland.[78] About 50,000 Jews from the vicinity of Białystok and the surrounding region were confined into a small, overcrowded area of the city, which was turned into the district's capital. The ghetto was split in two by the Biała River running through it. Most inmates were put to work in the slave-labor enterprises for the German war effort, primarily in large textile, shoe and chemical companies operating inside and outside its boundaries. Due to the ban on burying the dead outside the ghetto borders, a ghetto cemetery was established by the Judenrat. On 15 August 1943, the Białystok Ghetto Uprising began, and several hundred Polish Jews and members of the Anti-Fascist Military Organisation (Polish: Antyfaszystowska Organizacja Bojowa) started an armed struggle against the German troops who were carrying out the planned liquidation of the ghetto.[79][80], a process that was completed by November 1943.[81] Its inhabitants were transported in Holocaust trains to the Majdanek concentration camp and Treblinka extermination camps. Only a few hundred survived the war, either by hiding in the Polish sector of the city, escape following the Bialystok Ghetto Uprising, or by surviving the camps.

As the occupation progressed, German repression in Bezirk Bialystok intensified and most atrocities on civilian population were committed by German units and police from neighbouring East Prussia.[82] The Gestapo headquarters was located at 15 Sienkiewicza Street.[83] During the German occupation, a mass murder of Poles in the Bacieczkowski Forest (today lying on the border of Starosielce, Leśna Dolina and Bacieczki districts) was carried out by the Germans. In 1943, the German occupiers shot several hundred representatives of the Białystok intelligentsia: Germans placed men, women and children in ditches and shot them with automatic weapons. In July and August 1943, several hundred doctors, lawyers, priests, teachers, officials, students and pupils were killed. This crime deprived Białystok of much of its pre-war intelligentsia. A monument was erected in the site in 1980.[84]

The Germans operated a prison in the city,[85] and a forced labour camp for Jewish men.[86] Since 1943, the Sicherheitspolizei carried out deportations of Poles including teenage boys from the local prison to the Stutthof concentration camp.[87] The SS and police commander in Białystok was initially Werner Fromm.In May 1943 he was succeeded by Brigadenführer Otto Hellwig. The SS commander was responsible for the security police (Sipo), which was managed in the city by SS-Sturmbannführer Major Dr. Wilhelm Altenloh (to whom the Gestapo was subordinate). He was succeeded by Dr. Zimmermann. The head of the Białystok Gestapo was SS-Hauptsturmführer Lothar Heimbach, and the section for Jewish affairs was headed by Fritz Gustav Friedel. He was, on behalf of the Gestapo, the direct administrator of the ghetto.[88][89]

From the very beginning, the Nazis pursued a ruthless policy of pillage and removal of the non-German population. The 56,000 Jewish residents of the town were confined in a ghetto.[90] After the liquidation of the ghetto, according to data from the Government Delegation for Poland, Białystok was inhabited by over 63 thousand people, including over 49 thousand Poles (77%), about 11.5 thousand Belarusians (18%), and almost two thousand Russians (3%). The Germans took hostages and murdered people during interrogations at 15 Sienkiewicza and 50 Warszawska Streets and in other police stations and commands, and in the overcrowded prison at Szosa Południowa.[91] The number of victims in the camps grew: transit camps for Soviet prisoners of war and for Jews in the barracks at military base in Kawaleryjska street,[92] for those sent to work in Germany - in the area of the railway station and for those sentenced to forced labour at the military base in Kawaleryjska Street, and penal camps in Starosielce and Zielona. The camp at Kawaleryjska Street held about 23 thousand people and in all, about 95 thousand passed through this place. During the harsh winter of 1941–1942, mortality reached 100 deaths per day. By June 1944, roughly 4,000 Soviet prisoners and civilians from the USSR had been executed there.[93] German authorities also stripped Białystok’s economy. Factory machinery was dismantled and shipped away. The remaining textile operations produced only "hede", low-grade cloth made from waste materials. By 1942, all Polish-owned shops had been shut down. Craftsmen operated under strict control, and commercial activity was heavily restricted. [94]

Despite the repression, resistance efforts continued. In the last year of the occupation, a clandestine upper Commercial School came into existence. The pupils of the school also took part in the underground resistance movement. As a result, some of them were jailed, some killed and others deported to Nazi concentration camps. Anti-fascist groups emerged within weeks of the occupation, and over time, Białystok developed a well-organized resistance movement.

In the summer of 1944, heavy Soviet Forces pushed into the region as part of the Belostok Offensive: The 3rd Army managed to reach the outskirts of Białystok and even though encountered strong resistance from the LV Corps[95]

As the Germans began evacuating the city, widespread looting followed, lasting until July 26. On July 21 at 5:00 a.m., the prison in Kopernika street was evacuated. Prisoners were transported to Grajewo in two groups—one toward Zielona, the other to a transit camp on Żółtkowska Avenue. The Home Army’s intelligence unit collected information from the latter group. Around the same time, many men were forcibly conscripted to dig trenches. The roundup continued until July 25. Following the evacuation of offices and administrative structures, the Germans initiated a systematic campaign to burn the city. Special Brandkommando units composed of soldiers from the Russian Liberation Army were formed for this task and protected by a German armoured unit stationed in Dojlidy. Exit roads were secured by battalions of the Russian Liberation Army to prevent escapes.

The destruction began in the city center, focusing on key streets and infrastructure. Multi-story tenement houses—many Jewish-owned—on Lipowa, Sienkiewicza, Kupiecka, Zamenhofa, Równoległa, and surrounding streets were set ablaze. Other destroyed buildings included the hospital on Piwna Street, the slaughterhouse and cold store on Żółtkowska Street, and nearly all the railway infrastructure in Starosielce. The Lubomirski Palace, as well as local factories—such as the tobacco plant and Sokół factory on Warszawska Street, the Becker plush factory on Świętojańska Street, the timber factory on Cieszyńska Street, the textile factory on Sosnowa Street, the textile factory on Grunwaldzka Street, the Nowik textile factory on Mickiewicza Street and the tile factory on Bażantarska Street and multiple other facilities were also burned to the ground.[96] The Germans also burned down the building of the Pedagogical High School and the Exercise School on Mickiewicza Street. On the other hand, the Princess Anna Jabłonowska High School,[97] the Treasury Chamber and the modern building of the District Court on Mickiewicza Street and the building of the municipal theatre were bombed by the Soviet aircraft. The last troops destroying the city withdrew 26 July in the afternoon, when the Red Army was already visible on the outskirts of Białystok. The destruction of the city was completed by two-day (25 and 26 July) Soviet artillery fire. On the night of August 11–12, a final act of destruction, when the bridge on the bypass road at the powder magazine above the railway track to Grodno blew up as a result of the explosion of a time mine.

On July 20, 1944, before the Red Army entered Białystok, at the headquarters of the Białystok inspector Major Władysław Kaufman at 15 Wiktorii street in Bojary district, a briefing for unit commanders from the city was held, during which the orders of the district commander regarding the Operation Tempest were discussed once again. Combat tasks were to be carried out by commanders at the appropriate levels, and consisted in eliminating the Germans by all means. The Białystok-city district, strengthened as a result of the unification actions of the Home Army with other organizations, was to recreate the 10th Lithuanian Uhlan Regiment (dismounted). Martian Walter "Zadora" was appointed as the regiment's commander, and Czesław Hakke "Filip" was to become the chief of staff. As part of the preparations for the implementation of the Burza plan, information was collected on the dislocation of German forces in the city. It was assumed that when the Germans retreated, there would be an attack from within eight Home Army groups from the directions of Lipowa, Dąbrowskiego, Sienkiewicza, Słonimska, Warszawska, Mickiewicza, Mazowieka and Sosnowa streets[98] with an estimated strength of 2,400 to 3,000 people and at the same time partisans from other districts would come to help, so that a total of five thousand Poles would enter the fight. Junior commanders in the Polish underground pressured for a major office, while the higher command refused to execute it, assuming it would be a failure, with only a limited number of city-based units were present in the city and engaged in action. One notable group, of Roman Nowak "Ordon", the 1st Battalion of the re-created 10th Lithuanian Uhlan Regiment was concentrated in Bacieczki and attacked groups of German soldiers retreating from the city and individual cars were captured, 2 automatic rifles and 3 cars were burned. A 6-person Vlasov patrol that had ventured into the suburbs was also eliminated. There were also skirmishes with "Brandkommando" patrols in the city. In addition, a 15-person unit led by Piotr Miczunas "Adonis" entered to the city from the direction of Supraśl through the Napoleonic Route and Pieczurki area, supposing to protect inhabitants against robberies by gangs.[99] Over 20 rifles and a large quantity of ammunition was taken from a tenement building in Ogrodowa street. Units of Czesław Hake stayed in the city while Władysław Kaufman ordered all platoons to move to the surrounding forests in order to be then concentrated near Letniki.

In the city center, almost all the tenements and houses, the Branicki Palace, the Teachers' Seminary buildings, all the most important local and state buildings, industrial and production facilities, a new viaduct built just before the war were set on fire on Dąbrowskiego street, barracks of the 42nd Infantry Regiment and the 10th Lithuanian Uhlan Regiment in Wygoda district, Ritz Hotel, hospital buildings and a power plant.[100] Significant shelling occurred during the nights of July 18–19 and July 22–23, targeting the city center and worsening the devastation.[101] The last units left Bialystok on July 26 afternoon.[102]

Street names

In June 1941 the German Army entered Białystok as part of Nazi Germany's war on the Soviet Union. The renaming of streets could be seen in a city plan from 1942 issued by the German authorities. Among those changes of street names, can be noted:[68]

| Old name | New name |

|---|---|

| Aleja 11 Listopada | Richthofen Strasse |

| Angielska | Badenweiler |

| Antoniukowska | Nadrauen |

| Antoniuk Fabryczny | Nadrauen |

| Armatnia | Kanonen |

| Artyleryjska | Artillerie |

| Bema | Barbara |

| Biała | Mars |

| Białostoczańska | Kamerun |

| Botaniczna | Tapiauer |

| Branickiego | Goethe |

| Brukowa | Standarten |

| Czarna | Schwarze Casse |

| Częstochowska | Leipziger |

| Dąbrowskiego | Königsberger |

| Elektryczna | Kleindorf |

| Hetmańska | Insterburger |

| Jurowiecka | Post |

| Kilińskiego | Deutche |

| Kolejowa | Königzberger |

| Kupiecka | Markgrafen |

| Legionowa | Hamann |

| Marczukowska | Gotenhafener |

| Marmurowa | Marmer |

| Mazowiecka | Hochmeister |

| Mickiewicza | Reichsmarachall |

| Młynowa | Mühlen |

| Modrzewiowa | Albrecht |

| Niecała | Kirchen |

| Nowy Świat | Heidelberger |

| Odeska | Bromberger |

| Piłsudskiego | Langasse |

| Poleska | Preussisch |

| Pułaskiego | Heerbann |

| Sienkiewicza | Erich Koch |

| Sienny Rynek | Neuer Markt |

| Słonimska | Reinhard-Heydrich |

| Sosnowa | Nürnberger |

| Szlachecka | Posener |

| Szosa do Supraśla | Suprasler |

| Szosa do Zambrowa | Sürdring |

| Św. Rocha | Tannenberg |

| Świętojańska | Kant |

| Kościałkowskiego | Am Schlosspark |

| Wierzbowa | Trakenher |

| Wspólna | Hohenfriedberger |

| Zamenhofa | Grüne |

| Zwierzyniecka | Boeloke |

| Żelazna | Lobeer |

Renewed Soviet occupation

Just before the Soviets took over Białystok, the Białystok District of the Home Army, Colonel Władysław Liniarski assigned the city inspector Major Władysław Kaufman a new task consisting in conducting talks with the Soviet authorities: They concerned two issues: reaching an agreement with representatives of the Soviet side on the creation of a 100,000 Polish army corps from the inhabitants of the Białystok region and demand from the Soviet authorities that the areas east of the Curzon Line are part of the Polish state and cannot be incorporated into the USSR. Shortly before the Germans withdrew, a proclamation from the commander of the Home Army District, Liniarski, was posted on the city walls, informing the population that "In a victorious pursuit of the enemy, the Red Army has crossed the border of Poland. We are on the same side of the barricade in the fight against the common enemy".[103] The statement also declared that, by order of the Polish government and commander-in-chief, cooperation with the Red Army had begun—though its success would depend on the attitude of Soviet forces. This proclamation was printed at the copying point of the merged Home Army-Combat Organization "Wschód" at 31 Augustowska Street, located in the home of a member of the Propaganda Department of the "Nie" organization.[104]

In the order also issued on July 26, the population was decreed to surrender all weapons to State Security Corp posts within two days, suspend the activities of associations and societies (except for clandestine groups loyal to the Polish Government-in-Exile), banning public gatherings, alcohol sales, and the distribution of literature. He also warned against looting abandoned property. For the first time, voivode Józef Przybyszewski, the Delegate of the Government-in-Exile, signed an official document using his real name. This marked the beginning of the Polish underground civil administration’s attempt to assert power. In a proclamation issued the same day, Przybyszewski declared that the legitimate authority in the voivodeship belonged to the Government of the Republic of Poland and that his directives were binding for all civilians. He affirmed that the Home Army remained the only armed force acting on behalf of the Polish nation.[105]

According to the findings of the Home Army intelligence, there was no fierce defense of Białystok or its suburbs on the part of the Wehrmacht. On July 26, 1944, the first Soviet troops were approaching Dojlidy Górne (in the evening their reconnaissance team appeared on the Szosa Południowa). Here at night, apparently there were some battles, which actually consisted in the German artillery shelling the suburbs of Dojlidy, destroying a few houses. There can also be no talk of any infantry fighting in the evening of July 26 and at night in Dojlidy Górne, and because already at 6:45 p.m. on the Szosa Południowa (today Kopernika) a Soviet reconnaissance appeared from the direction of Dojlidy Górny, and half an hour later tanks appeared, driving towards Wiejska Street. Soon, Soviet army convoys also appeared in that area. Home Army units were indecisive with soldiers being sent towards Nowe Miasto and recalled four times. From the direction of Wasilków and Supraśl, Białystok was defended by the SS division, which also withdrew without a fight on the night of 26-27 July along the road in the direction of Jurowce, Osowicze and Leńce, hence Soviet units that entered the city from the district of Wygoda had not encountered fight.[103]

On July 27, 1944, Soviet troops entered Białystok.[106] People's Commissariat for State Security (NKGB) of the BSSR took the building at the 2 Sobieskiego street while SMERSH was located at 26 Słonimska street and 66 Boboli street. In the morning of the next day, the Home Army intelligence reported that the representative and minister of the Byelorussian SSR, in the rank of a colonel of the NKVD, had officially visited Father Aleksandr Chodyko in Białystok, stating that Białystok was the capital of Western Belarus. In the same day the Home Army Białystok Inspectorate commander Władysław Kaufman went together with delegate of the government-in-exile and voivode Józef Przybyszewski for a meeting with the Soviet city commandant general Lieutenant Pyotr Sobennikov at its headquarters at 35 Mickiewicza street. After an hour of waiting a Soviet delegation of several people appeared, including: general Sobennikov, a NKVD general, four officers from the staffs front armies and two ministers of the government of Western Byelorussia. The Soviet side declared that Przybyszewski has no right to organize local administration as according to the vote held in October 1939 the city became part of the Byelorussian SSR.[107][108] A report from the Home Army intelligence unit analyzed the situation, saying that "the advance of the Soviet troops was characterized by great restraint... The Germans used delaying actions with weak forces, small units, retreating according to their own plan. Of course, it was definitely not a walk in the park, as is best evidenced by the graves in the Military Cemetery in Białystok, but it was not a big battle either".

The party activists and partisans who carried out the orders of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Byelorussia did not know on the preliminary border agreement concluded on 25 July, according to which Stalin confirmed to the representatives of the Polish Committee of National Liberation his decision to transfer Poland to Białystok and Łomża. It was based on these decisions that on 27 July in the afternoon a delegation of the Polish National Liberation Committee arrived at the Krywlany Airfield to take over the city from Soviet hands. The delegation included: Edwarda Orłowska, who had appoint the Polish Workers' Party apparatus, Colonel Tadeusz Paszta, responsible for organizing the Office of Security and Civic Militia, and Zygmunt Zieliński with a team of 12 soldiers, appoint and fill Ministry of Defense powiat headquarters. The day after, they were joined by Major Leonard Borkowicz and the designated wojewoda Jerzy Sztachelski who were representatives of the Polish Committee of National Liberation in the Białystok Voivodeship.[109]

In early August, Soviet party activists were instructed to leave the territories newly recognized as part of "Lublin Poland". After arriving in Grodno they recreated however, the Białystok Regional Executive Committee (Polish: Białostocki obwodowy komitet wykonawczy) though decision about its liquidation occurred in December 1944.[110] Białystok continued to suffer sporadic German air raids, with bombing runs on the nights of August 28–29, September 6–7, and again on September 21–22, when bombs fell for the last time. the Germans were always repelled by Soviet anti-aircraft artillery fire, which managed to shoot down one of the planes on 31 August.[111]

Political situation

Beginning July 28, 1944, Soviet troops initiated daily forced labor roundups in Białystok, recruiting local men to fill bomb craters at the destroyed airport and build fortifications on the city’s outskirts. By August, newly established militia units assisted in these efforts. After the labor ended, mandatory political gatherings followed, where Soviet authorities conducted ideological indoctrination, denouncing the Polish Government-in-Exile and the Home Army.

As the NKVD intensified arrests of exposed Government Delegate officials and Home Army members, the Polish Committee of National Liberation (PKWN) began dismantling the remaining structures of Poland’s legal underground state: On 30 July 1944, PKWN activists posted appeals in the city informing that PKWN activists are the only legal authority in the city. The Polish government-in-exile represented by voivode Józef Przybyszewski and the mayor of Białystok Ryszard Gołębiewski, who, on July 27th (by other accounts July 28) revealed themselves to the Soviets as representatives of the legal Polish authorities and offered cooperation.[112] On August 2, Przybyszewski appointed Gołębiowski to the interim president of Białystok.[113] Initial discussions with Soviet city commander General Pyotr Sobennikov were unproductive. At first, Pyotr Sobennikov explained the Polish delegation that he has no appropriate authorization to discuss such topics with them and went away. After one hour, Sobennikov returned accompanied by NKVD general as well as generals from the staffs of the front armies and two ministers from the .[114] When mayor Ryszard Gołębiewski tried to discuss city matters with Soviet garrison commandant, Georgy Zakharov, he was replied that he should speak directly to Leonard Borkowicz who is "the supreme authority" in the city.[115] On August 3, soldiers of the 1st Tadeusz Kościuszko Infantry Division, under PKWN orders, attempted to disband the City Council appointed by the Polish Government Delegate. They tore down official notices and forcibly shut down the city hall at 30 Warszawska Street at 14:30. On 7 August NKVD arrested Przybyszewski at the next meeting of the Government Delegate and deported him to the Soviet Union.[116][117] On the same day, the Soviet military commander of Białystok invited president of Białystok, Ryszard Gołębiewski for talks. General Sobennikov banned the distribution of summonses and leaflets, and demanded that Gołębiowski make the Home Army soldiers surrender their weapons. Following the conversation, Gołębiowski left the Soviet command building, but the next day he was arrested by NKVD officers and deported to Kharkiv and from there sent to Camp 170 Dyagilevo next to Ryazan.[118] While Gołębiowski was allowed to return to Poland in 1947, Przybyszewski died in the Soviet Union.[117]

NKVD in cooperation with PKWN activists proceeded with the final liquidation Polish Underground State and its legal representatives.[119] On August 15, 1944, the then provincial commander of the Citizens' Militia, Lieutenant Tadeusz Paszta, closed the city government-delegate office located at the rectory of St. Roch's Church and disbanded the government-delegate's State Security Corps.[120] Another challenge was the resolution published by the Polish Committee of National Liberation on August 15, calling for mobilization of Polish men to join the Polish Armed Forces in the East.[121]

Due to the huge damage created by the war and unclarity as for whether the city would be part of the Soviet Union or Poland, economic recovery was slow. In addition to arbitrary roundups,[122]the Soviet authorities dismantled and sent to the Soviet Union many pieces of utilities and factories equipment that survived the war. Looting was widespread as well. Large units of Soviet soldiers located in the city's territory increased tensions with local population. Soviet soldiers stationed in the premises of factory no. 24 in Sosnowa street, Ruberg factory in Warszawska street, and kombinat no 5. a fact which prevented them from returning to normal activity. In Dojlidy district, in October 1944 an incident occurred when many fish were stolen from a church-owned pond, to be served as a food to the military field hospital which was established at the Lubomirski Palace. Parks were cut down with 300 cubic metre of wood was removed from Zwierzyniecki Forest in one week of October 1944 alone. Soviet soldiers dismantled factories and warehouses of their equipment and machinery. The railway workshops in Starosielce were totally deprived of the installation[123] and 30km of electric lines were cut and transported to the Soviet Union.

From the summer of 1944 to the end of 1945 Soviet authorities deported from the Central Prison in Kopernika street nearly 5,000 anti-communist underground soldiers to the Soviet Union. In the first week of November, two transports, totaling 2,000 prisoners, departed. The transport, which departed from the Białystok Fabryczny Railway Station Station on November 13th, contained 1,014 prisoners. They were sent, like the two previous deportations, to the notorious Camp 45 in Ostashkov. In 1944–1955, military courts in the Białystok Voivodeship sentenced over 550 people to death, of whom about 320 were murdered.[124] At the first meeting of the Municipal National Council (Polish: Miejska Rada Narodowa) in Białystok on 31 August 1944, by an election resolution of the council as chairman the council was elected Witold Wenclik, and vice-chairmen Józef Jankowski and Jan Pietkiewicz. On 30 May, Andrzej Krzewniak was appointed to that position (Polish: Przewodniczący MRN) and served until 1948.[125]

In parallel to the existence of Soviet security forces such as NKVD and SMERSH, the security apparatus of the Polish communist authorities began forming in the city with the establishment of territorial branches of the various security and intelligence agencies such as the Ministry of Public Security such as Voivodeship Office of Public Security at the voivodeship level, headquartered from 1946 to 1956 at 3 Mickiewicza Street, PUBP at the county level headquartered at 7 Warszawska street from 1945 to 1956 and MUBP at the municipal level, headquartered at 2 Staszica (then Monopolowa) street and headed by Piotr Grzymajło from 14 September 1944 to January 1946 when it was abolished.[126] Executions took place in seats of those organizations as well as in the Central Prison, Solnicki Forest, the military training ground at Zielona near Białystok (located at 53°08′50″N 23°16′53″E / 53.14722°N 23.28139°E), the KBW shooting range at Pietrasze Forest (located at 53°10′17″N 23°09′49″E / 53.17139°N 23.16361°E), and the military shooting range at the barracks on 100 Bema Street.[127]

Three NKVD regiments were sent to the city, numbering 4,500 soldiers and about 200 security officers. Mass arrests covered the entire area liberated from German troops. On November 8, 1944, the first transport left Białystok to the camp 45 in Ostashkov. Subsequent transports with AK and NSZ soldiers and additionally people serving the Nazis were sent east on November 12 and 22, December 26, January 30 and 31, 1945. Each Soviet "advisor" had at his disposal NKVD subunits of the 2nd Belorussian Front. They carried out arrests of those suspected of anti-Soviet and pro-German activities during the previous occupation. Independently of them, operations to combat the underground were also conducted by local NKVD units, which were part of the 64th Collective Division of the Internal Troops of the NKVD, deployed in Poland. On 19 October 1944, the 108th Border Regiment of this division arrived in Białystok. It numbered 1,400 soldiers. On 9 November, additional NKVD units arrived in the city, which was noticed by the Home Army intelligence, which noted reinforced patrols in the streets and stronger posts on the outskirts. The 108th Border Regiment of the NKVD was responsible for maintaining security in the city, protection of detention centres and prisons. It also set up checkpoints on access roads to the city. Even after Victory Day in May 1945, Soviet troops remained in Białystok. While control of daily civil administration slowly passed to the new Polish communist authorities, Soviet influence and military presence remained strong, firmly shaping the postwar political order in the region.[128]

See also

- Belarusian resistance during World War II

- War crimes of the Wehrmacht

- Soviet atrocities committed against prisoners of war during World War II

- German war crimes during the invasion of Poland

- Polish resistance movement in World War II

References

Citations

- ^ a b c Sychowicz, Krzysztof (2025-01-24). "Białostocczyzna między totalitaryzmami" (in Polish). Przystanek Historia. Retrieved 2025-04-25.

- ^ Straczyński, Karol. "Rozwój architektury Białegostoku w zarysie (XVII–XX w.)" (PDF). Podlaskie Czasopismo Regionalne. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2025-07-10.

- ^ Zielińska, Alicja (2014-07-14). "Po wojnie centrum Białegostoku było zniszczone aż w 80 procentach" (in Polish). Kurier Poranny. Archived from the original on 2025-07-10. Retrieved 2025-07-10.

- ^ Sadkowski, Jakub (2025-05-12). "Miasto okrutnie zniszczone przez wojnę. Tak wyglądał Białystok po II wojnie światowej" (in Polish). Radio ESKA.

- ^ Dobroński 2021, p. 35.

- ^ Fiedoruk 2019, p. 42.

- ^ Fiedoruk 2019, p. 44.

- ^ "Kalendarium dziejów Białegostoku" (in Polish). Informator Białostocki. Retrieved 2025-07-01.

- ^ Dobroński 2001, pp. 159–160.

- ^ "Służba zdrowia Białostocczyzny w II wojnie światowej" (PDF). Rocznik Białostocki. 1993. p. 477. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2025-07-09.

- ^ Kozak, Marek (2022-11-24). "Policja Państwowa województwa białostockiego we wrześniu 1939 r." (in Polish). Przystanek Historia. Retrieved 2025-02-10.

- ^ Zięckowski, Ryszard. "Od Seminarium do Uniwersytetu" (in Polish). Kurier Poranny. Archived from the original on 2025-07-09. Retrieved 2025-06-28.

- ^ Jankowski, Marek (2011-10-15). "Pierwsza ofiara wojny w Białymstoku. Ciało spoczęło w ogródku" (in Polish). Kurier Poranny. Retrieved 2025-06-29.

- ^ a b Truszkowski 2018, p. 316.

- ^ a b Kietliński 2019, p. 20.

- ^ Zielińska, Alicja (2016-09-16). "We wrześniu 1939 r. w Białymstoku nie było polskiego wojska" (in Polish). Kurier Poranny. Archived from the original on 2025-07-18. Retrieved 2025-07-17.

- ^ Poranny Kurier (13 September 2009). "Wysoki Stoczek. Reduta to pomnik chwały tych, którzy chcieli podjąć walkę, uratować honor miasta" (url) (in Polish). Retrieved 2019-12-18.

- ^ Zielińska, Alicja (2017-01-30). "Godnie wpisali się w historię Białegostoku" (in Polish). Kurier Poranny. Retrieved 2024-08-19.

- ^ a b "Telefon o 4 rano: Wojna!" (in Polish). Wspolczesna. 2004-08-31. Retrieved 2025-06-29.

- ^ a b Aleksander Dobroński. "Białystok we wrześniu 1939 roku" (url) (in Polish). Retrieved 2020-03-17.

- ^ "Kobiety z Podlasia – służba pod przysięgą" (PDF) (in Polish). Caritas Archidiecezji Białostockiej. 2024. p. 14.

- ^ "STANISŁAW GARNIEWICZ". zapisyteroru.pl. Archived from the original on 2025-07-09. Retrieved 2025-07-09.

- ^ Dobroński, p. 161.

- ^ Dobroński & Filipow 1993, p. 48.

- ^ Gajewski, Marek (2009). "Zbiór odznaczeń ostatniego komendanta PKU/KRU Białystok ppłk. Zygmunta Szafranowskiego" (PDF). Zeszyt Naukowy Muzeum Wojska (in Polish) (22): 192. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2025-07-08.

- ^ Gajewski, Marek (2009). "Zapomniany oficer - Tadeusz Kazimierz Kosiński (1891-1939)" (PDF). Zeszyt Naukowy Muzeum Wojska. p. 180.

- ^ Dobroński 1999.

- ^ Aleksander Dobroński (September 2016). "Prof. Śleszyński: 1 września w Białymstoku panował rodzaj entuzjazmu, wiary i siły" (url) (in Polish). Retrieved 2020-03-17.

- ^ Wardzyńska, Maria (2009). Był rok 1939. Operacja niemieckiej policji bezpieczeństwa w Polsce. Intelligenzaktion (in Polish). Warszawa: IPN. p. 55.

- ^ Lechowski, Andrzej. "17 września 1939 r. Tragiczna data w dziejach Polski" (in Polish). Kurier Poranny. Archived from the original on 2025-07-07. Retrieved 2025-07-07.

- ^ obiezyswiat.org. "Podlaskie wędrówki – Białystok" (url) (in Polish). Retrieved 2019-12-18.

- ^ "Wymiana okupantów" (in Polish). Przystanek Historia. 2019-03-12. Retrieved 2025-06-29.

- ^ Text of the Nazi–Soviet Non-Aggression Pact, executed 23 August 1939

- ^ "Miejsca represji komunistycznych lat 1944–56". SLA Samy Zbrodny. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- ^ "Dawny budynek Izby Skarbowej". polskaniezwykla.pl. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- ^ Fiedorczyk, Piotr; Siuchnicki, Krzysztof (2024). "Wojenne losy sądowników białostockich w świetle postępowań o uznanie za zmarłego i o stwierdzenie zgonu prowadzonych w Sądzie Grodzkim w Białymstoku w latach 1946–1950". Miscellanea Historico-Iuridica (in Polish). 2 (23): 564.

- ^ "75. rocznica deportacji kwietniowych" (in Polish). IPN. 2015-04-13.

- ^ "Sowieci zajęli Białystok w piątek. Pamiętny wrzesień 1939 (zdjęcia)". Kurier Poranny. 27 September 2016. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- ^ Grażyna Rogala. "Zespół więzienia carskiego, ob. areszt śledczy". Zabytek.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 14 January 2023.

- ^ Sylwia Wieczeryńska. "Wystawa "Seweryn Nowakowski – zaginiony prezydent Białegostoku" – od piątku". Dzieje.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 14 January 2023.

- ^ a b c "Ryszard Kaczorowski (1919 - 2010)". Uniwersytet w Białymstoku (in Polish). Archived from the original on 28 May 2022. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ^ "Białystok za pierwszego sowieta i parodia demokracji" (in Polish). ddb24.pl. Archived from the original on 2025-07-06. Retrieved 2025-06-21.

- ^ "Международное общественное объединение Развитие".

- ^ Dobroński, Adam (2011-01-02). "Lotnisko Krywlany. Rozbudowę zrobili Sowieci". Kurier Poranny. Archived from the original on 2025-07-08. Retrieved 2025-07-08.

- ^ a b c Wnuk 2007.

- ^ Czarnecki & Rembiszewski 2007, pp. 23–25.

- ^ "Деятельность ВВС и ПВО РККА в Западной Белоруссии и Западной Украины (сентябрь—ноябрь 1939 г.)" (in Russian). военно-исторический журнал. Archived from the original on 2025-07-07. Retrieved 2025-07-01.

- ^ Czarnecki & Rembiszewski 2007, p. 27-29.

- ^ Fiedoruk 2019, p. 58.

- ^ Czarnecki & Rembiszewski 2007, p. 31.

- ^ Wróbel 2020, p. 32.

- ^ "Koszary im. gen. Bema 14 Dywizjonu Artylerii Konnej (1921-1939) (BIAŁYSTOK)" (in Polish). Retrieved 2025-07-07.

- ^ "4-я танковая дивизия" (in Russian). Retrieved 2025-07-06.

- ^ Dobroński, Adam (2011-01-02). "Lotnisko Krywlany. Rozbudowę zrobili Sowieci". Kurier Poranny. Archived from the original on 2025-07-08. Retrieved 2025-07-08.

- ^ Czarnecki & Rembiszewski 2007, p. 33.

- ^ Fiedoruk 2019, p. 73.

- ^ Lechowski 2016, p. 61.

- ^ Czarnecki & Rembiszewski 2007, p. 46.

- ^ Dobroński 2001, p. 91.

- ^ "Сёньня — дзень ўзьяднаньня Заходняй і Усходняй Беларусі". Наша Ніва. 17 September 2008. Archived from the original on 30 April 2014.

- ^ "Мы помним о ссылках в Сибирь" (in Russian). Retrieved 2025-07-02.

- ^ "Michael Hope: Polish deportees in the Soviet Union". Archived from the original on 16 February 2012.

- ^ "W ciemny wagon nas jak w trumnę wsadzili" (in Polish). 2003-05-21. Archived from the original on 2025-07-07. Retrieved 2025-07-04.

- ^ "Zaginieni - 1939-1945 W świetle akt S W świetle akt Sądu Grodzkiego w Białymstoku" (PDF) (in Polish). IPN. p. 49.

- ^ Kuklo 2000, p. 51.

- ^ Winnicki 1998, p. 34.

- ^ Lechowski 2016, p. 43.

- ^ a b "Ulice Białegostoku" (PDF). IPN. Retrieved 2024-02-11.

- ^ Grabowski, Waldemar (2011). "Armia Krajowa". Biuletyn Instytutu Pamięci Narodowej (in Polish). No. 8-9 (129-130). IPN. p. 116. ISSN 1641-9561.

- ^ "Doctor Marek Wierzbicki of Institute of National Remembrance. Review of a book anti-Soviet conspiracy along the Biebrza, X 1939 – VI 1941 by Tomasz Strzembosz". Archived from the original on 11 June 2011. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- ^ "I NIE ZAWAHAC SIĘ PRZED OFIARĄ ŻYCIA - wspomnienia Pana Prezydentan Ryszarda Kaczorowskiego" (in Polish). Retrieved 2025-07-08.

- ^ Danilecki, Tomasz; Kaczorowski, Ryszard (2019-11-20). "Żyliśmy nadzieją" (in Polish). Przystanek Historia. Retrieved 2025-07-08.

- ^ "1941 - Wkroczenie wojsk niemieckich do Białegostoku. Pożar "Wielkiej Synagogi" przy ul. Suraskiej, początek nazistowskiej okupacji miasta". Institute Pamieci Narodowej. Retrieved 2022-10-19.

- ^ a b "Investigation into the murders of several Poles in Białystok and its area in June 1941". Archived from the original on 30 September 2012. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- ^ "Odsłonięcie tablicy poświęconej kapelanom wojskowym i duchownym poległym za wiarę i Ojczyznę" (in Polish). gov.pl. 2020-09-17. Retrieved 2025-06-20.

- ^ Goldhagen, Daniel J. Hitler's Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans and the Holocaust New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1997

- ^ Bender, Sara. The Jews of Byalistok. p. 93.

- ^ Geoffrey P. Megargee, ed. (2009). The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945. Vol. II: Ghettos in German-occupied Eastern Europe. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 886–871. ISBN 978-0-253-35599-7.

- ^ Mark, B (1952). Ruch oporu w getcie białostockim. Samoobrona-zagłada-powstanie (in Polish). Warsaw.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Mark, B. (1952). Ruch oporu w getcie białostockim. Samoobrona-zagłada-powstanie (in Polish). Warsaw.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Szymon Datner, The Fight and the Destruction of Ghetto Białystok. December 1945. Kiryat Białystok, Yehud.

- ^ "Kazimierz Krajewski, Shock in the Reich, Rzeczpospolita Daily". Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- ^ Marcin Zwolski. "Jak Zbyszek Rećko Wyprowadził" (PDF). IPN. Retrieved 2023-09-05.

- ^ "Zapomniana zbrodnia w Lesie Bacieczkowskim. 75 lat temu Niemcy zamordowali białostocką inteligencję". ddb24.pl. 18 July 2018.

- ^ "Schweres NS-Gefängnis Bialystok". Bundesarchiv.de (in German). Retrieved 14 January 2023.

- ^ "Zwangsarbeitslager für Juden Bialystok". Bundesarchiv.de (in German). Retrieved 14 January 2023.

- ^ Drywa, Danuta (2020). "Germanizacja dzieci i młodzieży polskiej na Pomorzu Gdańskim z uwzględnieniem roli obozu koncentracyjnego Stutthof". In Kostkiewicz, Janina (ed.). Zbrodnia bez kary... Eksterminacja i cierpienie polskich dzieci pod okupacją niemiecką (1939–1945) (in Polish). Kraków: Uniwersytet Jagielloński, Biblioteka Jagiellońska. p. 187.

- ^ Datner, Szymon (1957). "Niemiecki aparat wojskowy do walki z ruchem oporu w okresie drugiej wojny światowej". Biuletyn GKBZH w Polsce (9).

- ^ Gopaniuk, Kamil (2013-02-05). "Fritz Gustaw Friedel. Przez tego sadystę zginęło wiele osób". Archived from the original on 2025-07-08. Retrieved 2025-07-02.

- ^ "Bialystok". Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 26 July 2007.

- ^ Dobroński 2021, p. 153.

- ^ "Białystok, ulica Kawaleryjska 70/3" (in Polish). IPN - Śladami zbrodni. Retrieved 2025-06-15.

- ^ Zwolski 2013, p. 45.

- ^ Dobroński 2021, p. 155.

- ^ "Białystok Offensive Operation". codenames.info. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- ^ Zielińska, Alicja (2016-03-12). "Białostockie fabryki były sławne na cały świat". Kurier Poranny. Archived from the original on 2025-07-07.

- ^ "Historia szkoły" (in Polish). Retrieved 2025-07-02.

- ^ Kułak 1996, p. 11.

- ^ Kułak 1996, p. 14.

- ^ Wodociągi i kanalizacja białegostoku od czasóW najdawniejszych do 2015 roku, p. 192

- ^ Kietliński 2019, p. 26.

- ^ Kietliński 2019, p. 27.

- ^ a b Kułak 1996, p. 16.

- ^ Fiedoruk 2019, p. 124.

- ^ Kietliński & Lechowski 2014.

- ^ Soczak, Kazimierz (1967). "Wyzwolenie Mazowsza przez Armię Radziecką i Ludowe Wojsko Polskie w latach 1944-1945" (PDF). Rocznik Mazowiecki (in Polish). p. 85.

- ^ Kułak 1996, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Situational report of the head of intelligence at the Home Army Białystok District Command – the city of "Wiktor" from 17 August, p. 28.

- ^ Żarski-Zajdler 1966, pp. 88–90.

- ^ Wolna Praca : organ komitetów: Białostockiego Obwodowego i Miejskiego KP(b)B i Obwodowej Rady Delegatów Ludu Pracującego 1941.02.26 nr 24 (204).

- ^ Kułak 1996, p. 17.

- ^ Kułak 1996, p. 20.

- ^ "W Białymstoku będzie tablica upamiętniająca prezydenta miasta z 1944 r." (in Polish). dzieje.pl. 2017-07-23. Retrieved 2024-08-12.

- ^ Kułak 1996, p. 21.

- ^ Kułak 1996, p. 24.

- ^ "Wojna i okupacja (1939-1944)". Muzeum Powstania Warszawskiego. Retrieved 2025-07-06.

- ^ a b TVN24 2023.

- ^ Januszkiewicz, Julita (2017-04-07). "Odkrywamy Białystok. Ryszard Gołębiewski był prezydentem tylko tydzień. Zasługuje na naszą pamięć" (in Polish). Kurier Poranny. Archived from the original on 2025-07-09.

- ^ Zwolski 2013, p. 20.

- ^ Kułak 1996, p. 30.

- ^ "Polski Komitet Wyzwolenia Narodowego w Lublinie" (in Polish). Brama Grodzka - Teatr NN. Retrieved 2025-07-10.

- ^ Białous, Adam (2014-07-27). "27 lipca – zmiana okupanta" (in Polish). Nasz Dziennik. Retrieved 2025-07-09.

- ^ Kułak 1996, pp. 34–36.

- ^ Bialystok, BiałystokOnline pl. "70 lat temu do Białegostoku wkroczyli Sowieci". BiałystokOnline.pl.

- ^ "Powstanie, rozwój organizacyjny oraz główne problemy działalności białostockiej wojewódzkiej organizacji PPS w latach 1944-1948" (PDF). p. 130.

- ^ Zwolski 2013, pp. 84–87.

- ^ Zwolski 2013, pp. 91.

- ^ Kułak 1996, pp. 65–67.

Bibliography

- Michał Gnatowski; Daniel Boćkowski, eds. (2005). Sowietyzacja i rusyfikacja północno-wschodnich ziem II Rzeczypospolitej (1939-1941). Studia i materiały (in Polish). Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu w Białymstoku. ISBN 83-89031-69-8.

- Borchert, Marek (2017). "Inspektorat V Białostocki Armii Krajowej w latach 1941-1944 w świetle dokumentów opracowanych przez Władysława Żarskiego-Zajdlera" (PDF). Juchnowieckie szepty o historii (in Polish) (2): 163–181. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2025-07-13.

- Czarnecki, Witold; Rembiszewski, Henryk (2007). Armia Krajowa na Białostocczyźnie 1939-1945 (in Polish). Światowy Związek Żołnierzy Armii Krajowej Okręg Białystok.

- Fiedoruk, Andrzej (2019). Moje białostockie powidoki (in Polish). Buniak-Druk. ISBN 978-83-64319-05-1.

- Dobroński, Adam (1999). "Czy Białystok bronił się we wrześniu 1939 roku?" (PDF). Niepodległość i Pamięć (in Polish). 15 (6/2): 95–104. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2025-07-09.

- Dobroński, Adam (2021). Historia Białegostoku (in Polish). Fundacja Sąsiedzi. ISBN 978-83-66912-02-1.

- Dobroński, Adam; Filipow, Krzysztof (1993). "Dzieci Białostockie" : 42 pułk piechoty im. gen. Jana Henryka Dąbrowskiego (in Polish). Muzeum Wojska w Białymstoku.

- Kuklo, Cezary, ed. (2000). Białystok w 80-leciu. W rocznicę odzyskania niepodległości 19 luty 1919-19 luty 1999 (in Polish). Instytut Historii Uniwersytetu w Białymstoku.

- Kułak, Jerzy (1996). Pierwszy rok sowieckiej okupacji: Białystok 1944 1945 (in Polish). Białystok: Awadom.

- Kietliński, Marek (2019). Straty wojenne województwa białostockiego 1939-1945. Biblioteka Uniwersytecka im. Jerzego Giedroycia w Białymstoku. ISBN 978-83-7657-385-4.

- Kietliński, Marek; Lechowski, Andrzej (2014). Prezydenci Białegostoku (in Polish). Publikator. ISBN 9788386462278.

- Lechowski, Andrzej (2016). Sekrety Białegostoku (in Polish). Księży Młyn.

- Wnuk, Rafał (2007). „Za pierwszego Sowieta”. Polska konspiracja na Kresach Wschodnich II Rzeczypospolitej (wrzesień 1939 – czerwiec 1941) (in Polish). IPN. ISBN 9788360464472.

- Wróbel, Wiesław (2020). Białystok, którego nie ma (in Polish). Księży Młyn. ISBN 978-83-7729-375-1.

- "Objął funkcję prezydenta miasta, po tygodniu aresztowało go NKWD. "Zasługuje na naszą pamięć i szacunek"" (in Polish). TVN24. 2023-07-29. Retrieved 2024-08-12.

- Zwolski, Marcin (2013). Śladami zbrodni okresu stalinowskiego w województwie białostockim (in Polish). Białystok: IPN. ISBN 978-83-62357-25-3.