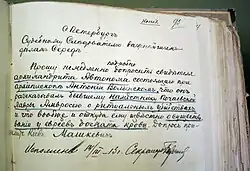

Beilis Affair

| Beilis Affair | |

|---|---|

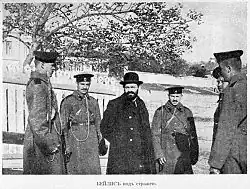

Beilis at the trial | |

| Started | September 25, 1913 |

| Decided | October 28, 1913 |

| Verdict | Acquitted |

| Defendant | M.-M. T. Beilis |

The Beilis Case was a judicial trial accusing Menahem Mendel Beilis of the ritual murder of 12-year-old Andrei Yushchinsky, a student at the preparatory class of the Kyiv-Sophia Theological School. The murder occurred on March 12, 1911, and the perpetrator was never identified.

The accusation of ritual murder was initiated by activists of Black Hundred and supported by several far-right politicians and officials, including the Minister of Justice Ivan Shcheglovitov. Local investigators, who believed the case involved a criminal murder motivated by revenge, were removed from the investigation. Four months after the discovery of Yushchinsky's body, Beilis, who worked as a clerk at a nearby factory, was arrested as a suspect and spent two years in prison.

The trial took place in Kyiv from September 25 to October 28, 1913,[1][2][3] and was accompanied, on one hand, by an active antisemitic campaign, and on the other, by nationwide and international public protests. Beilis was acquitted. Researchers believe the true perpetrators were Vera Cheberyak, a fence of stolen goods, and criminals from her home,[4][5][6][7] though this question remains unresolved.[8][9] The Beilis Case became the most high-profile trial in pre-revolutionary Russia.[10]

Victim

Andrei Yushchinsky (1898 – March 12, 1911) was the illegitimate son of Kyiv townsman Feodosiy Chirkov and Alexandra Yushchinskaya, who sold pears, apples, and greens in Kyiv.[11] He did not know his father: shortly after his birth, Chirkov abandoned his mother after living with her for only two years and was later drafted into military service. In 1905, Yushchinskaya married Luka Prikhodko, a bookbinder.

The boy grew up without proper supervision, as his stepfather, occupied with his workshop, only came home on Saturdays and Sundays. His upbringing was primarily overseen by his childless and relatively affluent aunt, Natalia Yushchinskaya, who owned a box-making workshop. She also paid for his education: at the age of eight, the boy was enrolled in a "shelter" or "kindergarten" at the Church of St. Theodore in Lukianivka, and the following year, he entered a teachers' seminary.[12] Andrei was deeply attached to his aunt and, when asked by a friend if he loved his mother and stepfather, replied that he loved his aunt the most.[13] The boy expressed a desire to become a priest ("he liked the uniform, he liked the position", explained his tutor, psalmist of the Church of St. Theodore, Deacon Dmitry Mochugovsky,[14] who worked with the boy for about nine months). In 1910, he enrolled in the Kyiv-Sophia Theological School at the Saint Sophia Cathedral.

The boy was described as capable, curious, and brave. Because he frequently walked at night and was unafraid of the dark, he earned the nickname "domovoi" (house spirit); at the same time, he "was reserved, did not get close to anyone, and kept to himself".[Notes 1]

Discovery of the body

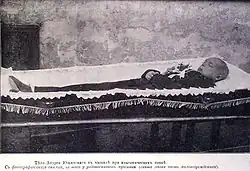

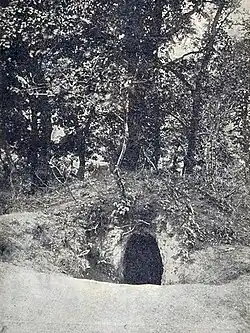

Twelve-year-old Andrei Yushchinsky disappeared on the morning of March 12 1911, while heading to school. On March 20, his body was discovered by boys playing in one of the small caves in the Lukianivka suburb, specifically by gymnasium student Yelansky. The body was covered with forty-seven stab wounds inflicted by an awl. The corpse was significantly drained of blood. It was determined that the cave was not the site of the murder.[15][16]

The cadaver was found in a sitting position, with hands tied, wearing only underwear and a single sock. Nearby were his jacket, sash, cap, and notebooks, rolled into a tube and tucked into a recess in the wall. A piece of pillowcase with traces of semen was found in the pocket of his tunic; it was later determined that this pillowcase had been used to gag the boy during the murder.[17][16]

The body was identified by inscriptions on the sash and notebooks. An expert analysis of the stomach contents (borscht from breakfast) established that he was killed 3–4 hours after eating, which, based on his mother's statement about the time of his last breakfast, indicated a time of death around 10 a.m. on March 12.[18][19]

Appearance of the "ritual" version

The version about the use of Christian blood by Jews for ritual purposes —the "blood libel"— has existed since ancient times. In the Middle Ages, such an accusation was widespread in Catholic Europe. By the 18th century, it had practically fallen out of use in Western Europe, while similar accusations continued to arise regularly in Eastern Europe. Thus, in Russia, precisely in the 19th century, a whole series of such cases was initiated. In none of them was such an accusation proven. Nevertheless, it arose again and again and served as a catalyst for antisemitic sentiments.[20][21]

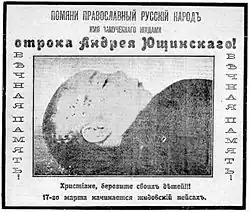

In the very first days after the discovery of the body, anonymous letters began to arrive to the relatives of the murdered boy, as well as to the prosecutor of the district court, the head of the detective department, and other officials, in which it was claimed that Andrei had been ritually murdered by Jews in order to obtain Christian blood for making matzo.[22] During the boy's funeral, hectographed proclamations were distributed with the following text: "Orthodox Christians! The boy was tortured by kikes, so beat the kikes, drive them out, do not forgive the shedding of Orthodox blood!"[23][24] With these proclamations, a member of the Black Hundred organization "Union of the Russian People" Nikolai Andreevich Pavlovich was detained, but the case against him was soon dropped. At the same time, the Black Hundred press first in Kiev, and then in the capitals, began to actively promote the theme of "ritual murder".[25][26][27] It was pointed out that the boy was killed on Saturday shortly before Jewish Passover, which that year fell on April 1.

The investigation was conducted by the head of the Kiev detective department Yevgeny Mishchuk; the preliminary investigation was carried out by the investigator for especially important cases of the Kiev District Court Vasily Fenenko, and supervision—by the prosecutor of the Kiev District Court Nikolai Brandorf. Also, to assist the investigation, an official for special assignments, assistant head of the detective department of the capital Mechislav Kuntsevich, was sent from Saint Petersburg for a short time.[28] They did not deny the possibility of the "ritual" nature of the murder, but after checking, they found no confirmation of this. Initially, the main version was mercenary motives: it was assumed that the boy's father, who had separated from his mother, had left a significant sum in Andrei's name, so suspicion fell on the boy's mother, his stepfather Luka Prikhodko, and a whole series of other relatives. Alexandra Prikhodko was arrested immediately after the initiation of the case, but then released; Luka Prikhodko was arrested twice (the second time—together with his father), but was also released.[29][30][31] It also turned out that the evidence against the relatives had been deliberately fabricated, and the confessions of the stepfather and uncle had been beaten out by the investigation.[32] The right-wingers openly declared that the Jews had bribed the police to direct the investigation down a false path.[33]

From the very beginning of the investigation, its course began to be influenced by the opportunistic and amateurish interference of the press, not only reactionary-right, but also democratic-liberal. Thus, the version of the involvement of Yushchinsky's relatives was voiced by the journalist of the liberal Kievskaya Mysl Semyon Barschevsky. When this version turned out to be unfounded, Kievskaya Mysl tried to accuse gypsies who had camped not far from the crime scene of the murder.[29]

The mention of the "ritual" version in the case appears for the first time only on April 22 in the testimony of Vera Cheberyak, who, regarding the corresponding conversations and proclamations at the funeral, states: "It seems to me now that the Jews probably killed Andryusha, since no one needed Andryusha's death in general. But I cannot provide you with evidence to support my assumption".[34][35]

Adoption of the ritual version by the investigation

Researchers note that the Beilis case undoubtedly had a strong political background.[36][37] Thus, Henry Resnik writes that in the conditions of the political crisis of 1911, the Russian right needed a high-profile event to strengthen their positions, and that is why an ordinary criminal murder began to turn into a ritual case.[38] The American historian Hans Rogger believes that the rise of the revolutionary movement in Russia became a pretext for the authorities to put a Jew on the dock as a ritual murderer.[39][Notes 2]

In February 1911, the State Duma for the first time began discussing a bill on the abolition of restrictions on Jews and, first of all, on the abolition of the Pale of Settlement,[40] at the same time a bill on the introduction of Zemstvo in the Western Territory was being considered, under which Jews had no voting rights. The struggle around the issue of Jewish equality was extremely acute at that moment, and the ritual version of Yushchinsky's murder became a key argument in antisemitic publications.[41][42][43][44]

On April 15, a meeting of the "Union of the Russian People" (URP) was held in Kiev, at which a decision was made to intensify measures to accuse Jews of murdering Yushchinsky.[45]

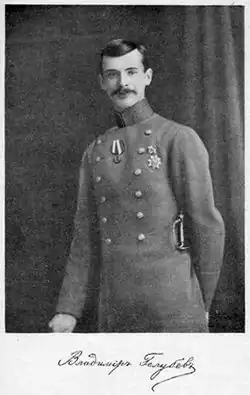

On April 17, members of the Union held a memorial service at Yushchinsky's grave and installed a cross; on the same day, they scheduled a Jewish pogrom, but after discussing the issue with the police chief, they postponed it until the fall; apparently, in view of the upcoming visit to Kiev of Tsar Nicholas II.[Notes 3] On the same day, the leader of the youth organization "Double-Headed Eagle", student Vladimir Golubev, the most active of the Kiev Black Hundreds, appealed to the Kiev governor with a demand to immediately expel up to three thousand Jews from Kiev according to the instructions of "patriotic" organizations, and having been refused,[46] he appeared to the first vicar of the Kiev metropolitan, Bishop Pavel, with the text of a "petition" to the highest name, in which the URP "most humbly petitioned for the expulsion of all Jews from Kiev, for they are engaged exclusively in immoral-criminal acts, not stopping even at shedding Christian blood for their religious needs, as evidenced by their commission of the ritual murder of Andrei Yushchinsky." The bishop crossed out the last phrase, stating that the ritual nature of the murder had not been proven, and in a mild form advised to abandon the idea of the petition.[47] As Doctor of Historical Sciences Sergei Firsov writes, "the Orthodox Russian Church itself ... never expressed its support (or at least 'understanding'—in the Black Hundred spirit) for the idea of the existence of ritual murders among Jews". That same day, the St. Petersburg Black Hundred newspaper Russkoye Znamya already published a sharp article about the "ritual murder" of Yushchinsky, accusing the authorities of inaction in solving this case.[48]

The next day, April 18, the faction of the right in the Duma decided to make a corresponding inquiry to the ministers of justice and internal affairs. The Ministry of Justice reacted immediately: on the same day, Minister Shcheglovitov appealed to the Minister of Internal Affairs and Chairman of the Council of Ministers Pyotr Stolypin with a request to pay special attention to the Yushchinsky case and composed a telegram to Kiev, entrusting supervision of the case to Georgy Chaplinsky, the prosecutor of the Kiev Court Chamber.[Notes 4] This was the beginning of the official politicization of the Yushchinsky case. Georgy Chaplinsky—a Pole who converted to Orthodoxy—demonstrated in every way his closeness to the extreme right, according to an employee's review, "in his conversations he struck with his extreme Judeophobia and the hatred with which he spoke about Jews".[49] According to Vasily Fenenko, Chaplinsky openly expressed his sympathy for Jewish pogroms.[Notes 5]

The draft inquiry, signed by 39 deputies, the first of whom was Vladimir Purishkevich, was introduced on April 29. The ritual murder was asserted in it as a fact and attributed to a criminal sect existing among Jews:[50][51]

Is it known to them (the ministers) that in Russia there exists a criminal sect of Jews who use Christian blood for some of their rituals, members of which sect tortured the boy Yushchinsky in the city of Kiev in March 1911? If known, what measures are being taken for the complete cessation of the existence of this sect and the activities of its members, as well as for the discovery of those of them who participated in the torture and murder of the minor Yushchinsky?

However, the inquiry was rejected by the Duma.[43][52]

At the same time, Shcheglovitov sent to Kiev the vice-director of the 1st criminal department Alexander Lyadov, who during his week-long stay in the city in early May finally directed the investigation onto the "ritual" track. According to Fenenko, "Lyadov arrived in Kiev with a ready opinion; in the office of the prosecutor of the chamber Chaplinsky, Lyadov told Chaplinsky in my presence that the Minister of Justice does not doubt the ritual nature of the murder, to which Chaplinsky replied that he is very glad that the minister holds the same view as he does".[53] It was Lyadov who introduced Chaplinsky to the leader of the "Double-Headed Eagle" organization Golubev, who from that moment began to exert the most important influence on the investigation. "Everyone in the Kiev administration had to reckon with him (Golubev); the governor-general also reckoned with him," asserted the former director of the Department of Police Stepan Beletsky. According to Mishchuk, the Union of the Russian People performed during the investigation the functions that are usually performed by prosecutorial supervision.[54] It was Lyadov who put pressure on the investigative team, forcing them to accept and check the "evidence" presented by the Black Hundreds.[55][56]

However, the position of Shcheglovitov and Chaplinsky contradicted the views of local police and investigative officials, whose strong resistance they had to overcome.[57] As a result, Prosecutor Brandorf was removed from the case.[Notes 6] At the same time, in early May, the famous detective, police captain Nikolai Krasovsky, was summoned to Kiev and entrusted with a secret investigation independent of Mishchuk. Soon after that, on May 29, Mishchuk, who, according to him, initially did not exclude the ritual version, but as the investigation progressed came to the firm conviction that the murder "was committed by the criminal world in order to simulate a ritual murder and provoke a Jewish pogrom," was also removed from the case, and since, despite this, he continued the search—a provocation was arranged against him, after which he was accused of forging evidence and arrested. The search was concentrated in the hands of Krasovsky. He was assisted by police sergeant Kirichenko and two detectives, Vygranov and Polishchuk, of whom Polishchuk later turned out to be a member of the Union of the Russian People.[58] Krasovsky behaved diplomatically: declaring to the Black Hundreds and persons connected with them that he did not doubt the ritual nature of the murder, at the same time he himself conducted the search in the direction that seemed correct to him.[59] When this was revealed, he was also removed from the case (in September) and then sent into retirement. Fenenko remained, but in fact the investigation began to be directed by the investigator for especially important cases Nikolai Mashkevich sent from Saint Petersburg, who became the key figure in the preparation of the "ritual" trial.[60] At the same time, Krasovsky, after complaining to Mashkevich that Black Hundred activists were interfering with his investigation, was arrested the very next day.[61]

-

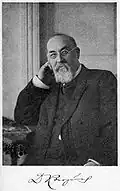

G. G. Chaplinsky

G. G. Chaplinsky -

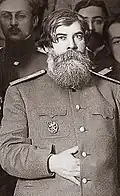

V. S. Golubev

V. S. Golubev

Examination

It was assumed that according to the ritual, the wounds should be inflicted on a living victim who is, if possible, conscious, and the goal is to drain as much blood as possible from it. From this followed a series of qualifying signs —the lifetime nature of the wounds and so on— which were considered as evidence of the ritual nature of the murder.

The autopsy, conducted by Doctor Karpinsky on March 22 (its results were immediately published in the press), noted no evidence allowing one to speak of the ritual nature of the murder. The autopsy results were deemed unsatisfactory, and on March 26, a new examination was conducted by Professor Obolonsky and prosector Tufanov. Their preliminary conclusions were against the "ritual" version. "Both the first and second autopsies rejected the assumption of the sexual and ritual nature of the murder," reported Metropolitan Flavian of Kiev in its wake. Since the Black Hundred press began to write that the examination allegedly established the ritual nature of the murder, Prosecutor Brandorf on April 15 turned to Tufanov for clarification and received from him the answer that "only the wounds to the head and neck were inflicted during Yushchinsky's lifetime, and the remaining injuries (stabs), in the area of the chest and heart, were caused already after death". To Chaplinsky's direct question about the ritual nature of the murder, the experts replied that they had no data allowing one to assume this and that it was most likely committed out of revenge, but they stated that "with further development of the investigation, they might be able to give a conclusion on the question of the ritual nature of this murder".[62]

The examination report was signed only on April 25, that is, a month after the autopsy and a week after Shcheglovitov's order. The conclusions set forth in it were clearly in favor of the "ritual" version:[63]

The nature of the weapon and the multiplicity of injuries, some superficial, in the form of stabs, indicate that one of the goals of inflicting them was the desire to cause Yushchinsky as much suffering as possible. No more than a third of the total amount of blood remained in his body; there is a negligible part of it on the underwear and clothing, and the rest of the blood flowed out, mainly through the cerebral vein, the artery at the left temple, and the veins on the neck. The immediate cause of Yushchinsky's death was acute anemia from the injuries received, with the addition of asphyxia phenomena.

These conclusions, which formed the basis of the accusation against Beilis, were unanimously protested by Russian and European specialists after the publication of the indictment, who pointed out that they contradict the factual material presented by the experts themselves: according to this material, the boy first lost consciousness from a blow to the head, then was strangled, and only after that —posthumously or at the moment of agony— most of the wounds were inflicted on him. They are mostly superficial in nature and cannot in any way testify to the intention to drain blood.[64]

Search for Andrei Yushchinsky's murderer

Parallel to the preparation of the trial, Chaplinsky gave an order to the head of the Kiev gendarme department Colonel Alexander Shredel to unofficially conduct a search for the true perpetrators of the murder.[65] Shredel had a similar order from the Minister of Internal Affairs Stolypin. Shredel entrusted this to his assistant, Lieutenant Colonel Pavel Ivanov.

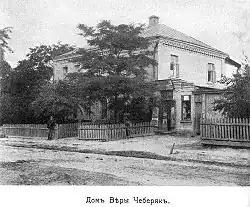

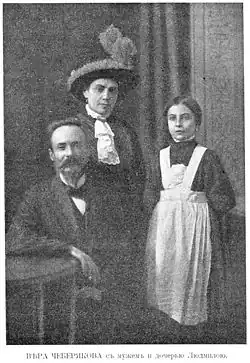

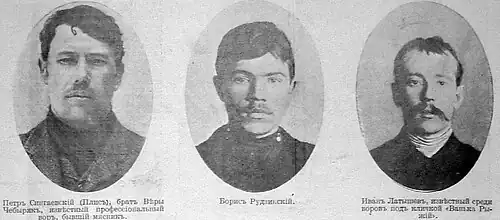

Meanwhile, the police's suspicion very quickly fell on Vera Vladimirovna Cheberyak (Cheberyakova), the wife of a minor postal-telegraph official Vasily Cheberyak and the half-sister of the professional thief Pyotr Singayevsky. The police knew Cheberyak well as the keeper of a thieves' den and a buyer of stolen goods; in the criminal world, she appeared under the nicknames "Cheberyachka" and "Verka-chinovnitsa". On the eve of the murder, on March 10, 1911, four professional thieves were arrested and brought to the detective department, identified as regular visitors to Cheberyak's den; then a search was conducted in Cheberyak's apartment, as a result of which two revolvers and cartridges were found.[66][30]

The Prikhodkos were previously neighbors of the Cheberyaks, and Andrei Yushchinsky continued to maintain friendship with their son Zhenya, his peer. Zhenya in a conversation with student Golubev initially stated that Andrei came to him on the morning of March 12 and they went together to play in the nearby Berner estate; but then during interrogations he began to deny this and claim that he last saw Andrei only about 10 days before the murder.[67] However, after the arrest of his mother, when control over him weakened, Zhenya confessed to Fenenko that Andrei came to him for gunpowder (Andrei had a homemade toy gun, and, according to relatives, he was concerned with obtaining gunpowder just before the murder). The lamplighter Kazimir Shakhovsky testified that on the morning of March 12 he saw Andrei together with Zhenya at the Cheberyaks' house, and Andrei was without books and a coat, and he could have left them, according to Shakhovsky, only at the Cheberyaks'. In Andrei's hands, Shakhovsky noticed a jar with gunpowder. Also, the police recorded a rumor in Lukyanovka that on the morning when the murder occurred, Andrei, in the presence of a third boy during play, quarreled with Zhenya; at the same time, Zhenya threatened to tell his mother that Andrei skipped classes, and Andrei in response—to report to the police that Zhenya's mother accepts stolen goods. According to the rumor, Zhenya immediately informed his mother about the threat, and this was the reason for the murder.[68]

The detailed course of the investigation remains unknown, since the special case on Cheberyak, references to which are in the documents, was not found already in the 1920s—apparently, it was deliberately destroyed. By June, the investigators no longer doubted that Cheberyak was one of the killers, although the motives for the murder remained unclear—as noted, the head of the search Mishchuk assumed that the criminals were provoking a subsequent pogrom in order to have the opportunity to safely rob. On June 9, Cheberyak was arrested by the gendarme department,[Notes 7] and Brandorf said that he issued the arrest warrant secretly from Chaplinsky. Indeed, according to Mishchuk's story, Chaplinsky expressed his displeasure to him: "Why are you torturing an innocent woman,"—and insisted that Mishchuk "not concentrate the search in the area where the body was found and where Vera Cheberyak lives." On July 13, Cheberyak was released on Chaplinsky's order, who, in turn, according to Brandorf's testimony, made this order at the categorical demand of Golubev, who stated that Cheberyak belongs to the "Union of the Russian People." On July 22, she was arrested again simultaneously with Beilis and released on August 7.[69]

The first thing she did after her release was to go to the hospital, where the seriously ill Zhenya was lying surrounded by detectives, and transport the dying child home in a cab. On August 8, Zhenya died, a week later his sister Valentina died. The reports of the detectives who were in the room at the moment of death describe Zhenya's last minutes as follows: in delirium he constantly repeated: "Andryusha, Andryusha, don't shout! Andryusha, Andryusha, shoot!" The mother constantly held him in her arms and, when he came to, asked: "Tell them (the agents) that I know nothing about this case," to which Zhenya replied: "Mom, don't talk to me about it, it hurts me a lot".[70]

There were persistent claims of poisoning, and the Black Hundred press directly wrote about the found "copper poisons." At the same time, Cheberyak and the Black Hundreds accused the Jews and Krasovsky of poisoning the children, whose detectives treated Zhenya to pastries, while Beilis's defenders accused Cheberyak; the latter opinion was held by certain "competent" people from the police's point of view.[Notes 8] The autopsy, in which Tufanov participated, noted dysentery bacilli in the intestines and no poisons except bismuth, with which Zhenya was treated in the hospital for dysentery.[71] Neighbors believed that the children got sick because after the arrest of their mother, out of hunger, they overate unripe pears.[72] In any case, Krasovsky notes that the mother neglected the sick children, took Zhenya from the hospital in a very serious condition, contrary to his insistence, did not send the girls—Valya and Lyuda, who was also ill but survived—to the hospital and clearly sought for the children to die.[73]

On September 14, the thief from Cheberyak's gang Boris Rudzinsky was arrested and immediately interrogated by gendarme Lieutenant Colonel Ivanov on the Yushchinsky case. On November 10, Zinaida Malitskaya, the saleswoman of a wine shop located right under the Cheberyaks' apartment, told Fenenko that on March 12 she heard unusual noise from Cheberyak's apartment, which made her alert. The door to Vera Cheberyak's apartment slammed, and some people stopped near the door. As soon as the door slammed, Malitskaya heard light children's and quick children's steps from the front door towards the adjacent room: apparently, the child was running there. Then quick steps of adults in the same direction were heard, then children's crying reached, and finally some fuss began. The Cheberyak children were not at home, and the child's voice did not resemble the voice of the Cheberyak children. "Even then I thought that something unusual and very strange was happening in Cheberyak's apartment... Having heard children's crying in Cheberyak's apartment that morning, it was clear to me that the child was grabbed and something was done to him".[74][75]

In those same days, Fenenko received information: Cheberyak, in connection with Rudzinsky's arrest, is very afraid that the investigation will find out who "Vanka-ryzhiy" and "Kolka-matrosik" are. Ivanov informed him that these are the nicknames of two thieves from Cheberyak's gang: Ivan Latyshev and Nikolai Mandzelevsky.[76] Latyshev was in custody, Fenenko immediately interrogated him regarding Yushchinsky's murder and met decisive resistance: "To the questions whether I visited Cheberyakova, I do not wish to answer until you tell me what you accuse me of, and although you, investigator, tell me that you do not accuse me of anything, I still do not wish to answer the questions". From this, Fenenko concluded that Latyshev was involved in the murder.[69]

On January 20, Shredel reported to the head of the Police Department Beletsky that he had "firm grounds to assume that the murder of the boy Yushchinsky occurred with the participation of the above-mentioned Cheberyakova and the deprived of rights criminal prisoners Nikolai Mandzelevsky and Ivan Latyshev." This was written just in those days when the case accusing Beilis of the ritual murder of Yushchinsky was completed and transferred to the court.

Further, the circle of Cheberyak's accomplices was determined. In particular, it was established that among the thieves in Cheberyak's circle, on March 12, Singayevsky, Rudzinsky, and Latyshev were at liberty in Kiev, and they left Kiev by express train to Moscow early in the morning of March 13; on March 16, they were detained in a Moscow beer hall and extradited to Kiev, but soon released. Kirichenko interrogated Rudzinsky's family and found out that on March 12 he was absent approximately between 8 and 12 a.m., and, coming home after 12 o'clock, demanded from his mother that she urgently redeem his pawned suit and discharge him, saying that he was going to Kovel.

All this gave Ivanov grounds to recognize the data collected by him as "completely sufficient material for accusing not Mendel Beilis, but Vera Cheberyak, Latyshev, Rudzinsky, and Singayevsky of the murder of Yushchinsky," to ask Chaplinsky for permission to arrest Cheberyak and Singayevsky (Rudzinsky and Latyshev were already in custody, and Latyshev on June 12 1912 threw himself out of the investigator's office window). Chaplinsky refused. Information about Ivanov's solving of Yushchinsky's murder was reported by Chaplinsky to the Minister of Justice, and by Colonel Shredel — to the Minister of Internal Affairs. Both these reports were ignored. At the same time, the preparation of the trial against Beilis continued.[77]

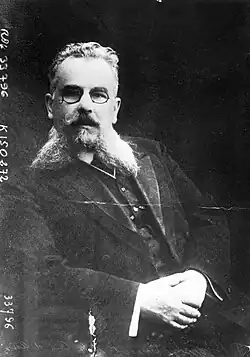

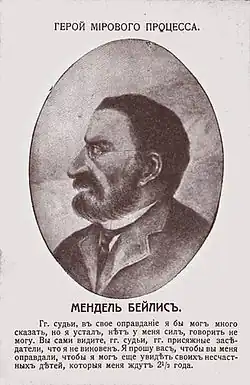

Beilis Affair

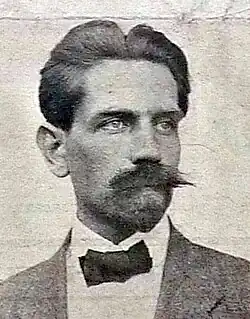

Menachem Mendel Beilis

Menachem Mendel Tevyeovich (Tovyevich) Beilis was born in 1874 in Kyiv[78] and was the son of a deeply religious Hasid, though he himself was indifferent to religion. He did not observe most religious rituals and worked on Saturdays. After completing military service, the 22-year-old Beilis married and began working at a brick factory[79] in Podil, at 2 Nizhne-Yurkovskaya Street. He became the father of five children. Beilis spent most of his adult life working as a clerk at Zaitsev's brick factory, owned by a friend of his father. Earning 50 rubles a month, he struggled financially, paying for his son's education at a Russian gymnasium and supporting a large family, often working from morning until late at night.[80] He maintained good relations with the Christian community, including the local priest. According to Maurice Samuel, his reputation was so strong that during the October 1905 pogrom, members of the Union of the Russian People assured him he had nothing to fear.[81][Notes 9]

Arrest

On July 22, 1911, 37-year-old Menachem Mendel Beilis, then a clerk at Zaitsev's brick factory, was arrested on suspicion of murdering Yushchinsky.[82][83][Notes 10]

According to Brandorf, the "guilt of Beilis was first invented" by Golubev.[54] Golubev surveyed the area and determined that the Berners' estate, where the body was found, adjoined the Jewish factory where Beilis worked as a clerk. Golubev initially told Chaplinsky verbally and later, during interrogations on May 5 and 6, formally testified to Fenenko that near the cave was "the estate of a certain Jew Zaitsev," where "his manager, some Jew named Mendel, resides… My personal opinion is that the murder was most likely committed either here or at the Jewish hospital. Of course, I cannot provide evidence for this".[84] Following this, Chaplinsky drafted a report to Shcheglovitov: "During a visit to Kyiv by the deputy director of the Ministry of Justice, Lyadov, the aforementioned student Golubev approached him and stated that he had significant material… Golubev is firmly convinced that Yushchinsky was killed by Jews for ritual purposes and expressed the opinion that the crime was likely committed at Zaitsev's estate, where the Jew Mendel resides…" The report was presented to the Tsar on May 18.[61]

Lamplighter Kazimir Shakhovsky, who in his first interrogation only stated that on March 12 he saw Andryusha with Zhenya near Cheberyak's house, claimed in his second interrogation that Beilis was friendly with Cheberyak.[85] On July 20, in Chaplinsky's presence, Shakhovsky stated that he had "forgotten to mention a very important detail" earlier: a few days later, he asked Zhenya how their outing with Andryusha went, and Zhenya replied that they couldn't play because "a man with a black beard, namely Mendel, the clerk of the factory estate, scared the children near the kiln at Zaitsev's factory. That's why I think this Mendel was involved in the murder".[86]

Immediately after, Chaplinsky ordered Beilis's arrest. Lacking grounds for a standard arrest, he requested N. N. Kulyabko, head of the security department, to detain Beilis under the extraordinary "Regulation on Enhanced Security." After issuing the order, Chaplinsky went to report to Shcheglovitov, who was vacationing at his estate in Chernihiv Governorate. That night, from July 21 to 22, Beilis was arrested at his home by a detachment of 15 gendarmes led by Kulyabko[83]. His nine-year-old son Pinkhas, a friend of Andryusha's, was also detained for three days at the security department. When Chaplinsky informed the investigators, Fenenko refused to prosecute Beilis. Brandorf argued to Chaplinsky that pursuing Beilis based on such dubious "evidence" was impossible, but Chaplinsky countered that he "could not allow an Orthodox woman to be charged in a Jewish case".[87] On August 3, Fenenko was forced to issue an arrest warrant for Beilis after a formal written order from Chaplinsky.[88] Beilis's lawyer, Vasily Maklakov, later called the arrest "a capitulation of the authorities to the right wing, of justice to politics".[89]

Following Kazimir Shakhovsky's testimony, his wife Ulyana claimed that a beggar Anna Volkivna told her that when Zhenya Cheberyak, Yushchinsky, and another boy were playing at Zaitsev's estate, a man with a black beard living there grabbed Andryusha in her presence and dragged him to the kiln. Beggar A. V. Zakharova was interrogated and denied having such a conversation with Shakhovskaya. Nevertheless, Ulyana persisted, and while intoxicated, told investigator Polischuk that her husband Kazimir personally saw Beilis dragging Yushchinsky to the kiln on March 12.[90]

Ulyana Shakhovskaya's claim about her conversation with Volkivna was corroborated by ten-year-old Kolya Kalyuzhny, who initially only said he knew Andryusha but was not part of his group. After speaking with Shakhovskaya and detectives, he returned to the investigator hours later with new testimony. In court, the Shakhovskys gave confused and contradictory testimony, revealing that detectives Vygranov and Polischuk had "visited" them, plied them with alcohol, and urged them to testify against Beilis, promising rewards or threatening exile to Kamchatka if they refused. Additionally, after his initial testimony, Shakhovsky was beaten by individuals likely connected to Cheberyak.[Notes 11]

The Shakhovskys' neighbor and Cheberyak's acquaintance, shoemaker Mikhail Nakonechny, told Krasovsky that Shakhovsky said he would "pin" the case on Beilis because Beilis had reported him to detectives for stealing factory firewood.[91][92] These were the only pieces of evidence against Beilis until November, when Kozachenko's statement was made.

Kozachenko's testimony

In November 1911, the (actual) investigation made significant progress: Malitskaya gave testimony. Her testimony outweighed the dubious evidence against Beilis. However, immediately after, on November 23, Ivan Kozachenko made a statement, becoming the third piece of evidence.[93]

One of Beilis's cellmates, Ivan Kozachenko, a police collaborator, gained his trust. Upon release, Kozachenko received a note from Beilis to his wife, in which the prosecution highlighted the request to give Kozachenko money (Beilis explained it was for a small reward) and the phrase: "Tell him who else is falsely testifying against me".[94] Kozachenko handed the note to the prison warden and claimed Beilis had tasked him with poisoning two witnesses: "the lamplighter", i.e., Shakhovsky, and "the Frog," a nickname for shoemaker Nakonechny, who consistently testified in Beilis's favor and exposed Shakhovsky as a false witness. The money for the poisoning was allegedly to come from Beilis's wife, with expenses covered by "the entire Jewish nation"; the strychnine was to be obtained from the Jewish hospital.[95]

"My dear, the person who delivers this note was in prison with me and was acquitted today. I ask you, my dear, to receive him as one of us; without him, I would have perished in prison long ago. Do not fear him; he can help greatly. Tell him who else is falsely testifying against me. Go with him to Mr. Dubovik.[Notes 12] Why is no one advocating for me?! The attorney Vilensky visited me. He lives at 30 Mariinsko-Blagoveshchenskaya. He wants to defend me for free; I haven’t met him personally, the authorities conveyed this. I’ve been suffering for five months; it seems no one is advocating, everyone knows I'm imprisoned innocently. Am I a thief or a murderer? Everyone knows I’m an honest man. I feel I won’t survive prison if I must stay longer. If this man asks for money, give him what’s needed for expenses. Is anyone trying to get me released on bail… These are my enemies falsely testifying against me, taking revenge because I didn’t give them firewood or allow them to cross the factory. The policeman is a witness that they were kept out; I wish you and the children well, greetings to everyone else. Pass my regards to Mr. Dubovik and Mr. Zaslavsky. Let them work to free me. November 22". The text was written by another prisoner, with a postscript in Beilis's hand: "Don't worry, you can rely on this man as on me".

Lieutenant Colonel Ivanov, after verifying Kozachenko's claims through his agents and finding them false, confronted Kozachenko, who fell to his knees, admitted his testimony against Beilis was false, and begged for forgiveness. Ivanov later shared this with the editor of the newspaper Kievlyanin, State Council member Dmitry Pikhno, and confirmed it during V. V. Shulgin's trial (1914) and before the Extraordinary Investigative Commission of the Provisional Government in 1917. In the latter, he added that he informed Fenenko, who offered to document it, but Chaplinsky forbade recording this fact. Consequently, Kozachenko's testimony remained a key evidence during Beilis's trial.[96][97]

The organizer of the false testimony was likely Deputy Prosecutor of the Kyiv District Court Andrey Karbovsky, whom Chaplinsky specifically used for such tasks — he was undoubtedly behind other false testimonies, like Kulinich's (see below); Beilis's lawyer Oskar Gruzenberg hinted at his involvement with Kozachenko's story in his defense speech.[98]

Vasily Cheberyak's testimony

Additionally, Vera Cheberyak's husband, Vasily, testified that "about a week before Yushchinsky's body was found, Zhenya, returning from Zaitsev's estate, told him that two Jews in unusual attire visited Beilis. Zhenya saw them praying. Immediately after the body was discovered, those Jews, according to Zhenya, left the apartment".[90] Cheberyak also stated that "a few days before the body was found, roughly three or four days, Zhenya came home out of breath and (…) said that he and Andryusha Yushchinsky were playing on the clay-kneading machine[Notes 13] at Zaitsev's brick factory, where Beilis saw him, chased him, while Beilis's sons stood somewhere in the factory and laughed. I don't know where Andryusha ran, and I didn't ask Zhenya about it." In later testimonies, however, two rabbis appeared, who, along with Beilis, allegedly grabbed and dragged Andrey in Zhenya's presence.

With this set of evidence (testimonies from the Shakhovskys, Kalyuzhny, Kozachenko, and V. Cheberyak), the case was finalized on January 5, 1912, and transferred to court for the first time.

Later, in March 1912, another fabricated testimony emerged from Beilis's cellmate. Convicted for forgery, Moisei Kulinich told Deputy Prosecutor Karbovsky that Beilis confessed to the murder; however, the falsification was so blatant that the prosecution did not pursue it in court.[99]

Private Investigation

Brazul-Brushkovsky's investigation

At the initiative of Henry Sliozberg and Kyiv lawyer Arnold Margolin,[Notes 14] a committee was established in 1911 to defend Beilis, aiming to identify the true perpetrators of Yushchinsky's murder. An active member of this investigation was journalist for Russkoye Slovo, who also collaborated with Kyivskaya Mysl, Sergei Brazul-Brushkovsky.[100] He was joined by detective Vygranov, who had previously coerced Shakhovsky into giving false testimony. Brazul-Brushkovsky actively engaged in the case since late August 1911, after Krasovsky's resignation, who, upon leaving, pointed him to Cheberyak: "the whole case, the entire mystery lies with Vera Cheberyakova; focus on Vera Cheberyakova, and if you succeed, the case will unravel." According to Brazul-Brushkovsky, judicial officials, compelled to pursue the case against Beilis while not believing in his guilt, encouraged him to gather evidence against Cheberyak to provide them with a "hook" to initiate proceedings against her. However, Brazul-Brushkovsky's actions were so reckless that they only compromised the private investigation. Brazul did not consider Cheberyak the direct killer (as he explained, not believing a woman could commit such a brutal murder) and thus began to court Cheberyak and her partner Petrov, hoping they would reveal the murderers. In particular, he took Cheberyak to a secret meeting with Margolin in Kharkiv (Margolin intended to act as Beilis's lawyer and thus could not directly interact with witnesses). Cheberyak made a sensational statement during the investigation and trial, claiming Margolin offered her 40,000 to take responsibility for the murder, which discredited Margolin.[Notes 15][101] Subsequently, these actions, particularly the Kharkiv trip, were heavily emphasized in the indictment: the prosecution portrayed them as a Jewish conspiracy to bribe Cheberyak and exonerate Beilis. Meanwhile, Cheberyak again fell out with her lover, Frenchman Pavel Mifle (previously, Cheberyak had blinded Mifle by throwing sulfuric acid in his face, but they later reconciled, and Mifle dropped legal action against her). Out of jealousy, Mifle attacked Cheberyak with brass knuckles, prompting Cheberyak to approach Brazul-Brushkovsky, claiming that Yushchinsky was killed by brothers Pavel and Evgeny Mifle, Luka Prikhodko, and Fyodor Nezhinsky (the boy's mother's brother, who had previously been arrested in connection with the case).[102] On January 18 1912, Brazul-Brushkovsky submitted a corresponding statement to the investigation. The investigation quickly determined these claims were baseless.[103] However, an enraged Mifle filed a denunciation against Cheberyak, resulting in her conviction during the trial to eight months in prison for falsifying entries in a debt ledger, and facing trial for escaping from a police station, where she had been detained under a false name the day before Andrey's murder on suspicion of selling stolen jewelry. This official conviction significantly undermined Cheberyak's credibility at the trial as a prosecution witness and a victim of slander.

Krasovsky's involvement

The private investigation truly gained traction in April 1912, when Nikolai Krasovsky, angered by his dismissal from the police and seeking professional rehabilitation, joined the effort.[102] He privately obtained all the investigation's findings to date from precinct officer Kirichenko and interviewed witnesses, including Cheberyak's friend Ekaterina Dyakonova, who provided details about the events on the day of the murder and the following days. According to Dyakonova, around noon on March 12, she and her sister Ksenia visited Cheberyak and found three men there: Singaevsky, Rudzinsky, and Latyshev. Their behavior was unusual, and a large bundle wrapped in a carpet lay in the corner by the bed. That night, Cheberyak, left alone, invited them to stay over, as she was frightened. The same occurred the next night, but all three women were so terrified that they fled the apartment and spent the night at the Dyakonovas' home. Ekaterina was convinced that Yushchinsky's body was in the carpet.[104] Ekaterina Dyakonova's testimony turned out to be fabricated, but this was only revealed at the trial.[105]

To obtain decisive evidence, Krasovsky, through a former student with ties to revolutionary circles, Makhalin, sent anarchist Amzor Karaev, a respected figure in the criminal underworld who agreed to act as an informant due to the case's societal importance, to approach Singaevsky (the only member of the gang, besides Cheberyak, still at large). Karaev alarmed Singaevsky with a false report that the gendarmerie was preparing to arrest him for Yushchinsky's murder. Panicked, Singaevsky, seeking help, revealed the murder's details to Karaev. Indeed, Rudzinsky, Singaevsky, and Latyshev killed Andryusha, suspecting him as the cause of recent failures (Cheberyak's arrest for selling a stolen ring on March 8; the arrest of four thieves from Cheberyak's den on March 9; a search of Cheberyak's apartment on March 10) ("because of that bastard, such good hideouts were busted").[106] When asked why they did not "dispose" of the body completely, Singaevsky replied: "That's how Rudzinsky's ministerial mind planned it" (evidently, Rudzinsky intended to stage a ritual murder). Latyshev, it turned out, was "weak in wet work" and vomited during the murder. The conversation continued in Makhalin's presence, who thus became a second witness to Singaevsky's confession. Karaev offered to take Andrey's belongings from Singaevsky to plant them on a Jew. However, this attempt to secure undeniable evidence failed, as Singaevsky wanted to consult Rudzinsky and Cheberyak first, who grew suspicious. Subsequent newspaper exposés fully exposed the ploy. Singaevsky later retracted his statements to Karaev and Makhalin at trial, and thus, the facts he disclosed in private to Karaev could not be accepted as legal evidence.[107] Researchers' opinions on Singaevsky's confession to Karaev diverge. Alexander Tager considers Karaev's testimony credible, while Sergei Stepanov believes the confession was fabricated by Makhalin and Karaev to extort money from Brazul-Brushkovsky.[108]

Brazul-Brushkovsky's statement

On May 6, 11 days before the scheduled start of the Beilis trial, Brazul-Brushkovsky submitted a new statement to Lieutenant Colonel Ivanov, outlining the gathered facts and identifying the true murderers. On May 30–31, he published the collected data in two Kyiv newspapers with opposing leanings — the liberal Kievskaya Mysl and the nationalist, monarchist, and antisemitic "Kievlyanin," edited by State Council member D. I. Pikhno (Pikhno was privately well-informed about the case's manipulations through Lieutenant Colonel Ivanov).[109] On June 2 1912, an attempt was made in the Duma to raise a ministerial inquiry on this matter. However, the Duma did not address the issue before June 8, and on June 9, it was dissolved.[110] Krasovsky was immediately arrested on charges of official misconduct but was acquitted by the court; Amzor Karaev was exiled to Siberia administratively, and special secret measures were taken to prevent his appearance at the trial (he was arrested during that time). However, the authorities could not ignore these facts, and the Beilis case was sent for further investigation on June 20, especially since the timing coincided with elections to the State Duma, making the start of the trial inconvenient for the authorities.[111] Confidence in Beilis's innocence became widespread among Kyiv residents.[112][113]

Following these publications, a new witness, barber Shvachko, identified Rudzinsky from a newspaper portrait. In the summer of 1911, Shvachko was detained with Rudzinsky. Shvachko reported overhearing a nighttime conversation between Rudzinsky and another professional thief, Krymovsky, during which Rudzinsky, in response to Krymovsky's question, "What about the bastard?" replied: "We finished him, the filthy snitch".[114] Earlier, according to Krymovsky, they had planned to rob Saint Sophia Cathedral, and it could be inferred that Andrey, a student at the cathedral's religious school, was intended to be used in this scheme.[115]

Further investigation

As a result of the further investigation conducted by N. Mashkevich, sent from St. Petersburg on the personal order of Shcheglovitov, the prosecution was supplemented with the following evidence:

- Vera Cheberyak's testimony, stating that before his death, Zhenya told her that Beilis had abducted Andryusha.

- Vera Cheberyak's 9-year-old daughter's testimony, Lyuda (Lyudmila). According to her, when the children went to Beilis's place for milk shortly before Andryusha's death, they saw two Jews in strange black attire, which frightened them greatly. Subsequently, Lyuda, Zhenya, Andryusha, Dunya Nakonechnaya, and other children went to play on the clay pits and saw that "Mendel Beilis and the Jew who sold hay at Tatarka and lived with Mendel <Faivel Shneerson> were running toward them. In the same direction, an old Jew, whom I had never seen before, with a fairly long gray beard, was slowly running toward the boys with Mendel and the hay merchant. Mendel's children also started to run but then stopped at the clay pit closer to the house where Beilis lived and just laughed." Beilis caught Zhenya and Andryusha; "Zhenya somehow wriggled free and ran home (...). I only saw Mendel Beilis dragging Andryusha by the hand toward the lower kiln." Later, according to Lyuda, Valya told her that she saw Beilis, the old man, and the hay merchant drag Andryusha to the kiln. "After that, we never saw Andryusha again".[116][117] These testimonies became central to the prosecution,[118][119] despite the fact that Dunya Nakonechnaya (daughter of M. Nakonechny) completely denied Lyuda's account.

As noted by Sergei Stepanov, Mashkevich ignored the fact that Vera Cheberyak's account emerged 16 months after the murder, only after accusations were leveled against her and following the deaths of the direct "witnesses"—Zhenya and Valya. None of the interrogated children, except Cheberyak's daughter Lyuda, corroborated this version. According to Stepanov, Mashkevich understood the flimsiness of these accusations but was fulfilling an "order" to pursue the ritual version.[120]

On January 30, 1912, Beilis, while in prison, was served a copy of the indictment, which had been approved by the judicial chamber 10 days earlier.[121]

Transfer to court

On May 13 1913, the further investigation was completed, and the case was once again transferred to court. Correspondence among senior officials indicates that they were aware of the evidence's weakness against Beilis and his evident innocence.[122]

In the summer of 1913, I. Shcheglovitov summoned the head of the Moscow criminal investigation department, Arkady Koshko, considered Russia's best detective, to St. Petersburg and tasked him with reviewing the case materials to highlight "as prominently as possible anything that could confirm the presence of a ritual." After a month of studying the case, Koshko informed the minister that he would "never have found it possible to arrest and detain him [Beilis] for years in prison based on the very weak evidence against him in the case".[14]

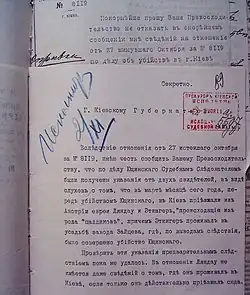

Kyiv Governor Alexei Girs wrote to the Minister of Internal Affairs, Makarov:[123]

Based on the available information, it is highly likely that the trial will result in the acquittal of the defendant. This is due to the fact that it will be impossible to prove the defendant's guilt in the alleged crime.

Makarov, in turn, wrote to Shcheglovitov on May 3, 1912:[123][124]

There is a strong possibility that the trial will result in a verdict of acquittal, given the evident lack of evidence that conclusively demonstrates the defendant's guilt.

Shcheglovitov himself recognized the extreme weakness of the evidence against Beilis and, in conversations with judicial officials, expressed hope in a skilled trial judge and a stroke of luck:[122]

Anyway, the case has attracted significant media attention and taken an unexpected turn, making it imperative to proceed with a trial. Failure to do so might lead to allegations of bribery against me and the government by Jewish parties.

Alexander Tager notes that the case's impact on Russia's political life became extremely significant. While it was initially used to obstruct projects for Jewish equality, by January 1912, it had become a cornerstone of the State Duma elections and the broader policies of the right-wing in Russia.[125] The situation was further intensified by the assassination of Prime Minister Stolypin in Kyiv in September 1911 by a Dmitrii Bogrov.[126]

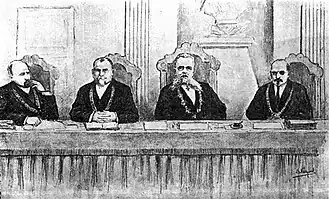

Trial

Organization of the Trial

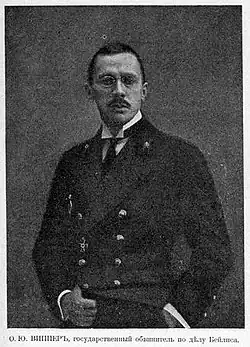

Some members of the Kiev Judicial Chamber believed the case should be dismissed due to lack of evidence.[127] None of the Kiev prosecutor's office staff were willing to act as state prosecutor, so Shcheglovitov had to send Oskar Vipper, deputy prosecutor of the St. Petersburg Judicial Chamber, to Kiev.[128] On the eve of the trial, and likely not by chance, an 1844 pamphlet titled Investigation into the Killing of Christian Children by Jews and the Use of Their Blood, attributed to Vladimir Dal, was republished.[129][130][131]

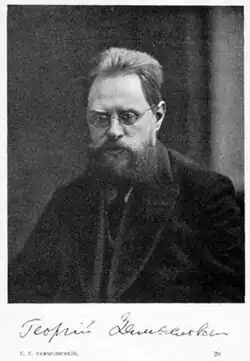

The trial began in Kiev on October 6, 1913, and lasted over a month. In addition to Vipper, the prosecution was represented by two private attorneys for the civil plaintiff, Yushchinsky's mother: Georgy Zamyslovsky, a member of the right-wing faction in the 4th State Duma, and the well-known antisemitic lawyer Aleksey Shmakov.[132] Beilis was defended by Kiev lawyer Dmitry Grigorovich-Barsky, who played a minor role in the trial, overshadowed by prominent lawyers from the capital: Alexander Zarudny, Nikolai Karabchevsky, Vasily Maklakov, and Oskar Gruzenberg; the latter was the only Jew among the defense. Also among the defendant's trusted representatives in court was Vladimir Nabokov, who attended as a correspondent for the newspaper Rech.[Notes 16]

The presiding judge, who initially conducted the trial fairly, adopted a clear prosecutorial bias toward the end. For example, to discredit Karaev, at the prosecution's request and despite the defense's objections, a letter from the imprisoned anarchist Feofilaktov, found during a search and hinting at Karaev's provocation and substantial financial reward, including for involvement in the "Beilis case," was read aloud. Not only were Feofilaktov's explanations during interrogation omitted, but his letter to the court, in which he clarified that he was merely repeating dark rumors to provoke Karaev into a frank conversation, was also (illegally) concealed from the jury.[133]

Prosecution's version

According to the prosecution, Yushchinsky was the victim of a long-planned human sacrifice, timed to coincide with the groundbreaking of a synagogue at the brick factory (investigation data indicated that five days before the murder, construction began on a building documented as a canteen but intended as a synagogue, which required a lengthy bureaucratic process to obtain construction permits).[Notes 17] For the sacrifice, Yushchinsky was allegedly targeted by tzadiks who arrived from abroad. Yushchinsky had been chosen as a victim long before, with surveillance established; initially, Beilis's acquaintance, Faivel Shneerson, allegedly from the renowned Chabad dynasty of tzaddikim, was supposed to lure Andrey to the factory by promising to show him his father (whom Andrey longed to find). However, since Andrey came to the factory with other children, Beilis allegedly kidnapped him and took him to a kiln, where the sacrifice was performed.

Later, the prosecution introduced a new version regarding the location of the sacrifice: during the investigation, a stable and adjacent office at the factory burned down, leading to the office near the stable being named the crime scene, with the fire attributed to an attempt to conceal evidence. The stable burned two days before its scheduled inspection under unclear circumstances.[134]

The boy's body was then carried through a hole in the fence and hidden in a cave. The prosecution suggested that Beilis's accomplices included foreign tzaddikim Etinger and Landau. All inconsistencies, contradictory testimonies, and other issues were explained by the prosecution as manifestations of an overarching Jewish conspiracy, which allegedly intimidated and bribed witnesses and even investigators (Krasovsky and Mishchuk). The prosecution devoted significant attention to the actions of Margolin and Brazul-Brushkovsky, seen as specific manifestations of this conspiracy.[85]

Witness testimonies

The prosecution had six witnesses: the Shakhovsky couple, Zakharova (Volkivna), the Cheberyak couple, and their daughter Lyudmila.[135] The trial revealed the falsehood of the testimonies on which the prosecution's case was based.

Mikhail Nakonechny, called as a prosecution witness, claimed that Shakhovsky deliberately slandered Beilis, that Beilis could not have seized Yushchinsky in broad daylight in front of many children without anyone knowing for so long, and that the children could not have been at Zaytsev's factory at that time, as they were playing near Cheberyak's house.[136]

Dunya Nakonechnaya, both during interrogation and at a face-to-face confrontation, refuted Lyuda Cheberyak's testimony, exclaiming indignantly at her story: "Who chased us away? Remember before you lie!" after which Lyuda burst into tears, saying, "I'm scared!" Lyuda, with genuine horror, stated that detectives threatened her with the same fate as Zhenya if she did not testify as required; yet, despite the prosecution's efforts, she persistently pointed not to Vygranov or Krasovsky but to Polishchuk, who had just given extensive testimony supporting the ritual version.[137] It was also revealed that in the winter of 1911, the children could not have gone to Beilis for milk, as he had sold his cow long before and was buying milk from a certain Bykova.[138] Moreover, interrogations of numerous factory workers established that on March 12, work was ongoing at the factory, with carters transporting bricks, making it difficult to commit a crime unnoticed, and Beilis was in the office, where he worked continuously. Vasily Cheberyak was caught by the defense contradicting his initial testimony to the investigator, which ended with: "I don't know where Andryusha ran, and I didn't ask Zhenya about it".[139] Witness Chekhovskaya testified that in her presence, in the witnesses' room, Vera Cheberyak coached the boy Nazar Zarutsky to claim that Beilis seized Andryusha in his presence, but the boy refused; this was confirmed by the boy himself at a face-to-face confrontation with Cheberyak, despite clear pressure from the prosecution and Cheberyak herself.[140] Vol kivna (Zakharova) did not confirm Shakhovskaya's testimony and said she knew nothing about the Yushchinsky case. Shakhovskaya's testimony about a conversation with Vol kivna was also contradicted by Nikolai Kalyuzhny, a boy present at their meeting on March 12.[141]

The mysterious tzadik Etinger and Landau, who turned out to be relatives of the factory owner Zaytsev, attended the trial and testified, revealing that neither had any connection to the case or to tzadik.[142][143] Shneerson also testified at the trial as a witness and turned out to be a Russo-Japanese War veteran and a small-scale hay trader, a very distant relative, if not merely a namesake, of the Chabad rebbes, and religiously indifferent (he even claimed never to have heard of Hasidim or the Chabad Shneersons).[144]

The Shakhovskys gave confused testimony, but it emerged that they were coached by Polishchuk and Vygranov to point to Beilis, and that Shakhovsky was beaten, likely by Cheberyak's people, which he did not deny. Shakhovsky confirmed a conversation with Zhenya and the story of a man with a black beard chasing the children away but now denied that Zhenya mentioned Beilis. Ulyana Shakhovskaya completely retracted her preliminary investigation testimony. Kozachenko did not appear in court; his written testimony was read, but it was not confirmed by his cellmate Kucheryavy and was directly contradicted by Pukhalsky's written testimony, who wrote Beilis's letter[145].

Two defense witnesses claimed that the pattern on a piece of pillowcase found in the victim's pocket resembled a pillowcase in the Cheberyak household, and one pillowcase in the common room disappeared after the murder.[146]

Vera Cheberyak at the trial

In reality, the trial centered not on Beilis (who was barely mentioned for entire days) but on Vera Cheberyak. She displayed remarkable composure and resourcefulness in court. A New York Times correspondent wrote: "Cheberyak continues to be the center of attention at the trial; she sits with the expression of a sphinx, and when confronted with witnesses testifying against her, she always finds an answer".[147] Nevertheless, numerous testimonies portrayed Cheberyak as an obvious criminal, and she contributed to this impression: besides the revealed attempts to coerce the boy Zarutsky into false testimony, she openly threatened witness Chernyakova in the courtroom, who made a corresponding statement, adding, "She is capable of anything".[148] Ultimately, even civil prosecutor Shmakov admitted it was plausible that Cheberyak could be an accomplice to the murder, but only as Beilis's accomplice. Shmakov's private diary reveals he had no doubt that Yushchinsky's murder was Cheberyak's doing.[Notes 18]

Makhalin and Singaevsky at the Trial

The events of the 17th and 18th days of the trial made a significant impression on the public: the interrogation of Makhalin, followed by the interrogation of Singaevsky and his confrontation with Makhalin. Makhalin made a favorable impression on the audience. Singaevsky denied everything, citing as an alibi that on the night of March 13, he, Rudzinsky, and Latyshev robbed an optical store on Khreshchatyk (Singaevsky and Rudzinsky confessed to this in March 1912 to establish an alibi, and the case was quickly closed). Gruzenberg's question about why a theft committed on the night of the 13th was incompatible with a murder committed on the morning of the 12th left him stumped. However, the prosecution came to the thief's aid: Zamyslovsky explained on his behalf that a robbery requires thorough preparation and is thus incompatible with the murder; Singaevsky merely nodded in agreement. During the confrontation with Makhalin, Singaevsky became flustered and, according to eyewitnesses, showed signs of "animal fear";[149] he was silent for several minutes, creating the impression that he was about to confess.[150] However, Zamyslovsky intervened, asking Singaevsky leading questions in a friendly tone. This gave the impression of direct collusion between the prosecution and criminals. "It is highly peculiar that the prosecutors have to shield heavily suspected individuals from judicial scrutiny," wrote Vladimir Korolenko.[151] Although Singaevsky did not confirm involvement in the murder, he confirmed knowing Karaev and Makhalin and several secondary details of their testimonies, significantly boosting their credibility, so much so that, according to police analyst Lyubimov, the public was convinced Beilis would be acquitted.[152][153]

Expert Examinations

During the trial, medical, psychiatric, and theological examinations were conducted to determine whether A. Yushchinsky's murder was ritualistic.[154]

On October 14, 1913, the court began reviewing the medical examination. First, the court fully read the protocol of the initial forensic autopsy of Yushchinsky's body, conducted by Kiev doctor T. N. Karpinsky on March 22, 1911, the protocol of the second forensic autopsy, conducted by Professor N. A. Obolonsky and prosector N. N. Trufanov on March 26, 1911, and their examination of individual parts of Yushchinsky's body and clothing on March 27, 1911.[155] Professor Dmitry Kosorotov and Trufanov were called to provide conclusions (Obolonsky had died by then). The defense proposed their own experts — Warsaw professor of surgery A. A. Kadyan and court surgeon Professor Evgeny Pavlov.[155] On October 15, the court asked all four experts to address questions about the nature of the injuries on Yushchinsky's body. After a day-long discussion, the experts could not reach a consensus, and on the morning of October 16, the court asked them to present their conclusions separately, which they did.[156]

According to Professor Kadyan, "Yushchinsky certainly lost blood from the wounds, but there is no evidence of deliberate exsanguination". According to court physician Pavlov, "Stabs to the heart area, like bullet wounds, cause massive internal bleeding and minimal external bleeding. These wounds are not a means to collect blood. It would be far more convenient to collect blood from one large wound if such a wound had been inflicted on Yushchinsky… It is impossible to kill a person without blood, and it is impossible to judge the killers' plan…"[157] Bekhterev also confirmed that there were actually 14 wounds on the right temple, as noted by Dr. Karpinsky during the first autopsy,[158] not 13 as the prosecution claimed, attributing a kabbalistic significance to the number as a key indicator of the ritual nature of the murder (one wound was double, from two overlapping blows).[159]

The experts supporting the prosecution —physician Professor Dmitry Kosorotov and psychiatrist Professor Ivan Sikorsky, a well-known Kiev Russian nationalist[160]— backed the prosecution's version. It was revealed after the February Revolution that Kosorotov received 4,000 rubles from the secret funds of the Police Department for his testimony.[161][162] The defense protested Sikorsky's examination, noting that his lengthy speech on Jewish ritual murders far exceeded his competence as a psychiatric expert; however, the court ignored this protest. Sikorsky's examination sparked outrage in the professional community: Professor Vladimir Serbsky described it, using Sikorsky's own terms, as a "complex qualified crime";[163] the Journal of Neuropathology and Psychiatry stated that Sikorsky "compromised Russian science and covered his gray head in shame," etc.[164] The Psychiatric Society issued a resolution deeming Sikorsky's examination "pseudoscientific, inconsistent with the objective data from Yushchinsky's autopsy, and not in line with the norms of the criminal procedure code".[157] Psychiatrist Mikhail Buyanov, noting the widespread rejection of Sikorsky's examination by colleagues, wrote that "psychiatrists have never been so united and principled in expressing their disgust at the political abuse of psychiatry".[165] The XII All-Russian Pirogov Medical Congress in spring 1913 passed a resolution against Sikorsky's examination, and later that year, it was condemned by the International Medical Congress in London and the 86th Congress of German Naturalists and Physicians in Vienna.[166]

In the theological examination, the defense was represented by prominent Hebraists: academician Pavel Kokovtsov, considered one of the greatest Hebraists and Semitologists of his era;[167] Professor of the St. Petersburg Theological Academy Ivan Troitsky, prominent Jewish religious figure and Moscow state rabbi Yakov Maze, and Professor Pavel Tikhomirov, who demonstrated the absurdity of accusing Jews of using blood for ritual purposes. Earlier, during the initial transfer of the case to court, a similar conclusion was provided by Professor of the Kiev Theological Academy Alexander Glagolev.[168][63]

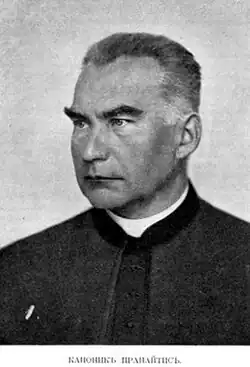

No Orthodox Church representatives agreed to serve as prosecution experts, so the confirmation of ritual murders in Judaism was assigned to a Catholic priest from Tashkent, Iustin Pranaitis, who had been effectively exiled to Central Asia for fraud and faced charges of blackmail.[169][162] Pranaitis argued that Judaism mandates hatred toward non-Jews and ritual murders, citing the Talmud and kabbalistic treatises.[170] However, the defense exposed his complete ignorance of Jewish religious literature (he could not answer a series of questions about Talmud sections); he refused to point out the cited passages in the Jewish text and ultimately admitted to quoting the Talmud from a falsified German translation. Shmakov inadvertently further discredited Pranaitis: in an attempt to prove the misanthropy of the Jewish religion using not only the Talmud but also the Old Testament, he posed several Bible-related questions to Pranaitis, who chose to evade them[171]. According to a police report, "due to his dilettantish knowledge, Pranaitis's examination carries little weight"[172]. Prominent Hebraists Troitsky and Kokovtsov, along with Tikhomirov, highlighted the fundamental prohibition on consuming blood in Judaism and demonstrated that Jewish religious tradition recognizes universal morality and the moral obligations of Jews toward non-Jews who follow the so-called "Seven Laws of Noah" (general moral rules given, according to tradition, to all humanity), and that Talmudic morality can be expressed in the Gospel formulation: "Do to others as you would have them do to you".[173] A weakness in the Hebraists' presentations was their limited familiarity with specific antisemitic literature, which prevented them from directly addressing some of Zamyslovsky and Shmakov's questions based on that literature. In other cases, however, they, along with Tikhomirov and Maze, demonstrated forgeries in translations and arbitrary interpretations of out-of-context quotes by their opponents.[174][63] Ultimately, the prosecution lost both the psychiatric and theological disputes.[175]

-

Prof. I. A. Sikorsky

Prof. I. A. Sikorsky -

Prof. D. P. Kosorotov

Prof. D. P. Kosorotov -

V. M. Bekhterev

V. M. Bekhterev -

I. Pranaitis

I. Pranaitis -

Academician P. K. Kokovtsov

Academician P. K. Kokovtsov -

Prof. I. G. Troitsky

Prof. I. G. Troitsky -

Rabbi Yakov Maze

Rabbi Yakov Maze -

Prof. A. A. Glagolev

Prof. A. A. Glagolev

Defense

The defense generally supported the following version of Yushchinsky's murder. After the arrest of four thieves and a search at Cheberyak's on March 10, the gang members believed someone had betrayed them. On the morning of March 12, instead of going to school, Yushchinsky met Zhenya Cheberyak, and they wandered around the city outskirts. During a quarrel, Andryusha threatened Zhenya that he would reveal the thieves' den in his mother's apartment, which he knew about since he often spent time at the Cheberyaks'. Zhenya immediately told his mother, overheard by Ivan Latyshev, Boris Rudzinsky, and Pyotr Singaevsky, who were at Vera's at the time. Luring Andryusha to the Cheberyak house with Zhenya's help, the thieves killed him and dumped the body in a cave at night, then left for Moscow, where they were arrested on March 16.[66] Like the prosecution, the defense also relied on some absurd testimonies and dubious witnesses.[176]

For example, Krasovsky's opinion about Yushchinsky's potential criminal tendencies, which could have made him useful in a cathedral robbery, was not confirmed by any witness. It was revealed that Ekaterina Dyakova, who claimed to have seen something wrapped in a carpet being carried out of Cheberyak's apartment, saw it in a dream. Makhalin and Karaev turned out to be former police informants whose services were discontinued due to their complete unreliability.[177]

Nevertheless, the defense attorneys successfully demonstrated the inconsistency of the charges against Beilis. V. A. Maklakov pointed to the following facts indicating Vera Cheberyak's involvement in Yushchinsky's murder:

- Andryusha went to the Cheberyaks' before his death, but Vera concealed this.

- Until Beilis's arrest and Brazul-Brushkovsky's public exposés, Vera did not report that, according to her children, Beilis had abducted Andryusha — even when she herself was suspected and arrested.

- Kirichenko's testimony that the mother forbade Zhenya to "talk" about the murder.

- The testimony of lamplighter Shakhovsky, who last saw Andryusha at the Cheberyaks' house with Zhenya.

- The circumstances of Zhenya Cheberyak's death (the fact that the mother took the dying child from the hospital, which can only be explained by a desire to keep him under constant control; Zhenya's delirious ravings as evidence that he was haunted by scenes of the murder; Vera's behavior, extorting a statement of her innocence from her son until the last moment).

Even Zamyslovsky acknowledged the persuasiveness of the evidence gathered by the defense against Cheberyak.[178]

Maklakov also highlighted blatant biases in the investigation: despite evidence, Cheberyak was not arrested, and evidence against her was not pursued; hairs found on Andryusha's body were compared only with Beilis's, not other suspects'; the clay on the body and clothing was compared with that of Zaytsev's factory but not Cheberyak's house; a carpet from Cheberyak's house, allegedly with bloodstains, was not properly investigated, etc. Regarding the accusations against Beilis, the defense dismissed the key testimony of young Lyuda Cheberyak, pointing out the absurdity of the assumption that a child's abduction in broad daylight, witnessed by many, would not become immediately known (the prosecution effectively acknowledged this absurdity but refused to comment). "You can only chase a chick in a henhouse in front of an audience!" Grigorovich-Barsky remarked ironically. Witness Mikhail Nakonechny also insisted that if the children had witnessed such an event, the entire street would have known about Yushchinsky's abduction within an hour.[179] The defense also rejected Kozachenko's testimony as provocative and absurd (Nakonechny, whom Beilis allegedly tried to poison, consistently gave testimony favorable to Beilis).

Maklakov also noted that the second expert examination refuted the data on which the prosecution relied: the boy was not undressed before the murder but killed clothed; his hands were not tied during the murder (they were tied only after death); he was killed in an unconscious state after severe blows to the head; the claim that the killers intended to drain his blood was not supported by the new examinations, as no major arteries were hit, and the wounds were stab wounds, not cuts; the blows were aimed at the heart, meaning the killers' sole goal was murder. According to the defense, the murder was spontaneous, explaining its brutal nature: lacking a suitable weapon, the killers repeatedly stabbed the stunned boy with a sharp object —likely an awl— trying to hit the heart until he finally died. Afterward, they staged a "Jewish ritual murder" by manipulating the body and possibly distributing corresponding leaflets at the funeral.[180]

In his speech following Maklakov, Gruzenberg provided a detailed justification of Cheberyak's guilt, addressing all evidence against her and refuting the prosecution's objections.[181]. In particular, Gruzenberg drew the judges' attention to Singaevsky's indirect admission: when asked if he was offered to plant Yushchinsky's belongings on a "tzaddik," he replied, "It was Makhalin who suggested it." However, Gruzenberg notes, such a suggestion would only make sense if Singaevsky had confessed to Makhalin his involvement in the murder and knowledge of the belongings' whereabouts. Zarudny devoted his speech primarily to refuting the prosecution's arguments regarding the "blood libel".[182] Grigorovich-Barsky demonstrated the insignificance of the evidence directly against Beilis.[183]

Jury

The authorities deliberately manipulated the selection of jurors to secure a guilty verdict. Jurors were specifically chosen from less-educated citizens;[184][185][186][187] the authorities sought to ensure that jurors were prejudiced against Jews.[188]

The jury included seven peasants, two burghers, and three minor officials. As Vasily Shulgin noted, "There was much talk and gossip in Kiev about this. When, in a minor criminal case, the court had three professors, ten educated individuals, and only two peasants among the jurors, in the Beilis case, ten out of twelve had only a rural school education, and some were barely literate".[189] According to police official Dyachenko, "The evidence against Beilis is very weak, but the prosecution is well-presented; the uneducated jury might convict due to ethnic animosity." It later emerged that five jurors, including the foreman, were members of the Union of the Russian People. The jurors were under constant surveillance before and during the trial: during the trial, they were isolated from the "outside world" and served by gendarmes disguised as bailiffs, who regularly reported on the jury's moods and overheard remarks.[190]

To exert moral pressure on the jurors, the prosecution even brought and displayed the relics of Gabriel of Białystok, canonized by the Orthodox Church in 1820 in connection with a "blood libel".[191]

Before the verdict, commenting on the jury's composition and the possible trial outcome, Korolenko wrote:[192]

The ordeal to which it has been subjected before the eyes of the world is severe, and if the jurors emerge from it with honor, it will mean that there are no longer conditions in Russia under which a ritual accusation can be extracted from the people's conscience.

Verdict

According to Vladimir Korolenko, the presiding judge's summary was biased and effectively amounted to a new prosecutorial speech, prompting a protest from the defense.[193][194] The jurors were presented with two questions: one regarding the fact of the murder and another regarding Beilis's guilt; the first question combined the fact of the murder, its location, and its method. Thus, by affirming the murder, the jurors had to simultaneously acknowledge that it occurred at Zaytsev's factory through multiple stab wounds, causing profuse bleeding and exsanguination.[195][Notes 19].

The jurors returned a positive verdict on the first question and a negative verdict on the second (regarding Beilis's guilt), and on November 10, 1913, at 6 p.m., Beilis was acquitted and immediately released.[196]

In literature, mainly of an antisemitic nature, there is a claim that the jurors' votes were evenly split. This claim first appeared immediately after the trial in the St. Petersburg newspaper Novoe Vremya.[197][198] with reference to a juror who allegedly confided in Yushchinsky's mother. There is a story that during the initial discussion of the verdict, seven jurors voted for conviction; but when it came to the final vote, one juror, a peasant, stood up, crossed himself before an icon, and said, "No, I don't want to take sin upon my soul—he's innocent!"[199] However, opponents of the split-vote claim argue that the jurors' votes could not have been known, as they were protected by the secrecy of the deliberation room, upheld by law.[198]

Beilis and other involved individuals' future

Shortly after the trial concluded, Beilis left Russia with his family. He lived for some time in Palestine and died in 1935 in the United States, having written the book The Story of My Sufferings.[200] The book was published in Yiddish and was first translated into Russian only in 2005.[201][202]

In January 1917, Zamyslovsky published a book about the Beilis case, funded by 25,000 rubles from a secret fund.[203] Golubev died on the front during World War I, Pranaitis and Shmakov died before the revolution, and Sikorsky in 1919.[204]