Auniati Satra

| Sri Sri Auniati Satra | |

|---|---|

The singhason (throne) of the main idol Govinda in the Manikut of the Auniati Satra | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Hinduism |

| District | Majuli |

| Deity | Govinda |

| Festivals | Raasleela, Paal Naam |

| Location | |

| State | Assam |

| Country | India |

| Geographic coordinates | 26°56′25″N 94°07′26″E / 26.9402°N 94.1238°E |

| Architecture | |

| Type | Assamese |

| Creator | Sri Sri Niranjana Deva Goswami (first satradhikar), Swargadeo Jayadhwaj Singha (patron king) |

| Completed | 1653 CE |

| Inscriptions | Assamese, Brajavali |

Sri Sri Auniati Satra is a satra or monastery located in the Majuli river island in Assam, India, that adheres to the Brahma Sanghati of the Ekasarana Dharma, a socio-religious and cultural movement initiated by Srimanta Sankaradeva, who was born in 1449 CE. It is one of the four "raj satras" or royal satras associated with the Ahom dynasty. It is the first satra patronised by the kingdom. It is usually believed that this satra was established in the year 1653 CE, with the initiative of Ahom king Jayadhwaj Singha, the first head monk or satradhikar being Sri Sri Niranjana Deva Goswami, even though different opinions exist.

The monks of the satra are udaseen Vaishnavas, meaning, they are celibate and avoid every worldly affair to focus entirely on Krishna, who is the supreme deity in Ekasarana Dharma and considered to be Param Brahma, the ultimate reality. Out of the sari bostu, or the four objects of prime importance in Ekasarana, namely Deva, Naam, Guru and Bhokot, Deva is given the most importance. Krishna is worshipped as Govinda in this satra[1]. Monks are trained in the thoughts of Sankaradeva and other preceptors, as well as Satriya life, theatrical performance called bhaonas, playing instruments like khol and taal and Sattriya dance. Many festivals, like Paal Naam, Ras Lila, Janmashtami, tithis of Sankaradeva and Madhavadeva, Bihu etc. are celebrated in this satra.

Etymology

The name "auniati" is traditionally believed to have come from the words "auni", which is a variety of betel and "ati", which means a place with high altitude.[2] It was built at an elevated place where the auni variety of betel used to grow, giving the satra its name. Kavichandra Dvij, in his "Keshava Charita Pada", writes:[3]

"Aunipan ek brikhyot asil

Tar xomipot zotu xotro xazisil

Etekexe auni asi nam xotro kohe

Dokhyine Dihing nodi mohabege bohe"

(There was an auni betel tree

Near that a satra was built

Therefore, it is named Auni Asi Satra

In its south, the river Dihing flows fast)

History

The exact year in which the satra was established is a matter of debate. The most commonly accepted theory places the origin of the satra in 1653 CE.[4] This was the time when the area was under Ahom rule, with Sutamla as the king. The establishment of the satra was a part of his bid to provide patronage to the Hindu faith, whereby he asked the pathak of the Kurubahi Satra to set this new satra up. After the establishment of the satra, he adopted the Vaishnava faith and received the name Jayadhwaja Singha from the first satradikar of the Auniati Satra.[5] However, other historians believe that the satra was actually established at the behest of Sutamla's predecessor king Sutingpha in the year 1644 CE.[4][6] Yet another opinion is that Jayadhwaj Singha got it established as a "raj satra" in 1656, donating land and paiks or labour. The Satsari Assam Buronji states that the foundational pillar of the home of the Gosain was laid in 1656 CE.[7] Auniati was the first satra to be patronised by the Ahom kingdom.[8]

The Sri Sri Auniati Satra is associated with the Brahma Sanghati, one of the four orders of Ekasarana satras. It is the most tolerant of Brahminical practices out of the four, and has historically been headed by Brahmin monks. This sanghati has historically maintained ties with the Koch and Ahom monarchy. The founder of this sanghati, Sri Sri Damodaradeva, had initiated Koch king Naranarayana into the Ekasarana fold.[9] On the other hand, the first satradhikar of the Auniati Satra, Sri Sri Niranjana Deva Goswami had initiated the Ahom king Jayadhwaj Singha into the Vaishnava fold,[5] effectively Sanskritising the dynasty. While the Ahoms, who migrated from southeastern China in the 1200s had their own religion, they began adopting Hindu ways since the time of Suhungmung, particularly Brahminical Shakta ways, often persecuting Ekasarana monks. Despite this, the Ahom dynasty's formal adoption of Hinduism only took place with Jayadhwaja Singha's initiation into the Vaishnava fold under the Sri Sri Auniati Satra.[8] The Auniati Satra became one of the four "raj satras" or royal satras,[4][9] the others being Dakhinpat, Garamur and Kuruwabahi. The Ahom kings considered Auniati to be of the highest position among the various satras.[2] After the initiation of Jayadhwaja Singha, the Ahom kings largely spared the Vaishnavas of the Brahma Sanghati from persecution, but continued to persecute the monks of the satras of the other sanghatis (except during the rule of Gadadhara Singha, where even the satras of the Brahma Sanghati faced persecution).

The relationship between satras of the Brahma sanghati and others has been complex historically. During the reign of Jayadhwaj Singha, the abbot of the Mayamara Satra, one of the primary satras of the Kal Sanghati, had to go into hiding in fear of persecution by the king. It was at the instance of the Auniati abbot that he was brought back.[10] During the reign of Gadadhara Sungha's son, Rudra Singha, satras of the Brahma Sanghati were patronised (Rudra Singha even accepted initiation under the Auniati satradhikar Sri Sri Harideva Goswami),[6] while restrictions were placed on other satras. Non-Brahmin satradhikars were barred from initiating Brahmin disciples by the king.[11] This was done in a meeting where both Brahmin and non-Brahmin mahantas were present, and allegedly, the Brahmin Mahantas sided with the king, infuriating the non-Brahmin Mahantas.[8] During the reign of his son Siva Singha, the stature of Shaktism rose even more. Following astrological advice, Siva Singha offered his throne to his three queens, Phuleswari Devi, Ambika Devi and Sarveswari Devi, with Phuleswari being the chief queen. Phuleswari Devi was a staunch Shakta and tried to make Shaktism the state religion. Once, she invited the adhikars of the major satras to a Durga Puja function and after the event, made the mahantas and gosains of other sanghatis bow their heads before the satradhikars of the Sri Sri Auniati and the Sri Sri Garamura Satra, further infuriating them.[8][12] During the Moamaria rebellion against the Ahom monarchy, which took place from 1786 to 1789, the rebels who were associated with the Kal Sanghati burned the royalist satras, including the Auniati Satra.[13]

Satradhikars

The first head monk or satradhikar of this satra was Niranjanadeva Goswami and the current one is Pitambaradeva Goswami. The following is the list of the satradhikars of Auniati Satra:[14][15]

- Sri Sri Niranjana Deva Goswami (1653 to 1658 CE)

- Sri Sri Keshavadeva Goswami (1658 to 1726 CE)

- Sri Sri Ramachandradeva Goswami (1726 to 1727 CE)

- Sri Sri Damodaradeva Goswami (1727 to 1737 CE)

- Sri Sri Harideva Goswami (1737 to 1760 CE)

- Sri Sri Pranaharideva Goswami (1760 to 1785 CE)

- Sri Sri Lakshminathadeva Goswami (1785 to 1804 CE)

- Sri Sri Padmapanideva Goswami (1718 to 1821 CE)

- Sri Sri Kusharadeva Goswami (1821 to 1838 CE)

- Sri Sri Dattadeva Goswami (1838 to 1904 CE)

- Sri Sri Kamalachandradeva Goswami (1904 to 1922 CE)

- Sri Sri Leelakantadeva Goswami (1922 to 1926 CE)

- Sri Sri Hemachandradeva Goswami (1926 to 1983 CE)

- Sri Sri Vishnuchandradeva Goswami (1983 to 1998 CE)

- Dr. Sri Sri Pitambaradeva Goswami (1998 CE to present)

Organisation and activities

Deity

Being a part of the Ekasarana Dharma, Krishna is worshipped as the supreme deity. Adhering to the Brahma Sanghati, the worship of idols is allowed in this satra, unlike some other sanghatis. The primary deity is worshipped as Sri Sri Gobindo Mohaprobhu, and his idol was brought in from Jagannath Puri in what is now the Indian state of Odisha.[2] In addition, other idols of Krishna are also worshipped, namely, Bansigopala, Madana Mohana and Bhuvana Mohana, who are all worshipped together with Gobindo Mohaprobhu.[16] During the time of Raslila, Sri Sri Gobindo Mohaprobhu is placed in a throne and worshipped.

Monkhood and responsibilities

The overall responsibility of overseeing all the activities of the Satra, like in other satras, rests on the head monk, or the Satradhikar.[17] Following the satradhikar, the next highest position is held by the Deka Adhikar.

Auniati monks are kewoliya, which means they are celibate. They are udaseen Vaishnavas (literally, indifferent), meaning they leave every worldly thought and focus entirely on Krishna.[2] Many join the satra as monks at very young ages. The satra arranges for both their formal (secular) education and training on the thoughts of Sankaradeva, Sattriya or monastic culture and the rules of monkhood.[18] Young monks leave ties with their families, reside in the satra premises and partake in its activities. The monks are dressed very simply in a white cotton dothi and angavastra, they are bare-chested and barefoot. Only the adhikar wears an angavastra decorated with a golden motif. They do not have shaved heads, on the contrary they wear long hair, following the example of the founder Sankardev who is represented with long hair. They eat vegetarian food. They participate in daily prayers. They live in range of houses known as "Hati".

They are taught the art of Gayan Bayan, which is singing (particularly the works of preceptors such as the borgeets) and playing instruments such as the khol and taal. The style of dance developed in the satras, called Sattriya, is recognised as one of India's eight major classical dance forms by the Sangeet Natak Akademi,[19] the Government of India and other scholars of Indian culture.[20] Natua, Apsara, Sutradhar, Ozapali (Panchali and Dulari), Sali, Jumura, Krishna Gopi Nritya, Maati Akhara and Gayan-Bayan are some of the dances practiced in this satra.[5] In addition, theatrical performances called bhaonas are practiced and performed on various occasions.

The laity who wish to associate with the satra but are unable to adopt monkhood in its entirety are initiated into the fold via institutions called xoron and bhojon.[2] Xoron luwa (literally, taking shelter) is the ceremony whereby a member of the laity accepts the Satradhikar as guru, and vows to follow certain principles preached in the Ekasarana dharma, such as devotion to Krishna, forgoing the consumption of alcohol, treating guests at home well etc. Bhojon luwa is a more extensive version of it.

Festivities

Several festivals are organised in the Satra, associated with the Ekasarana faith, such as the anniversaries of preceptors and various occasions marking events in the life of Krishna.

_of_Kamalabari_Satra.jpg)

A major festival associated with the Auniati Satra is the Paal Naam, first organised at the satra in 1695 by the fifth Sattradhikar, Hari Dev Goswami. It is celebrated annually in the Assamese month of Kartika, from the 25th to the 29th day.[5][21] During the festival, a naam nouka (“boat of the Name”) is placed at the centre, and continuous naam (chanting of the name of God) is performed, symbolising that the divine name is the vessel that carries devotees across the ocean of maya (illusion) to moksha (liberation). The boat used during this festival is on permanent display in the museum.

Other festivals celebrated include the tithis or anniversaries of the two principal preceptors of Ekasarana Dharma, Srimanta Sankaradeva and Sri Sri Madhavadeva; the Ras festival, celebrating Krishna's dance with the gopis of Braj; Janmashtami, celebrating the birth of Krishna; the three Bihus, marking different phases of agriculture in Assam etc.[21]

Influence

Performing arts

The monks of the Sri Sri Auniati Satra have been involved in numerous cultural and literary activities for centuries. The monks are routinely trained in theatre (bhaona), dance (Sattriya), singing (borgeet) and playing instruments (khol and taal).[5][18] Sattriya is one of the eight major classical dance forms of India. The monks of the Sri Sri Auniati Satra are often invited as delegations for Sattriya performances at various places, including the Indian Republic Day celebrations in New Delhi; in the presence of the President of India at the Rashtrapati Bhawan and other cultural institutions such as the National Museum in Delhi and various places in India and abroad.[2]

Literature

The monks of the Sri Sri Auniati Satra have over hundreds of years, engaged in the writing of several manuscripts and books. Several of these are works of play, such as[22] Godaporbo, Bhismoporbo, Bhorotagomon etc. by Sri Sri Dattadeva Goswami, Prahlad Soritro, Birat Porbo etc. by Kamalachandradeva Goswami, Tripur Toron by Lilakantadeva Goswami, Dondi Porbo, Droupodir Xomonwoy, Sri Krisnor Jonmolila, Jonmastomi etc. by Sri Sri Hemachandradeva Goswami, Jotanol Gitabhinoy, Dut Krisno, Bolisolon, Mohix Mukti etc. by Vishnuchandradeva Goswami etc.

Charita Puthis are a distinctive genre of Ekasarana literature, where hagiograpphies of the faith's gurus are written. Among the Charit Puthis, the charitas of Sri Sri Damodaradeva, Sri Sri Vansigopala Deva and Sri Sri Harideva were composed in the Sri Sri Auniati Satra itself.[22]

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the Sri Sri Auniati Satra played an important role in the development of modern Assamese literature. The first Assamese newspaper was published by Baptist missionaries, by the name of Orunodoi, in 1846. Soon after that, in the year 1871, the Sri Sri Auniati Satra began the publication of the second oldest newspaper in the Assamese language, Asam Bilasini.[23] The Auniati satradhikar Sri Sri Dattadeva Goswami personally oversaw the procurement and use of the "Dharmaprakasha Yantra", a modern printing press, for the purpose.[22] Some other periodicals published by the Sri Sri Auniati Satra include Assam Dipika (1976), Assam Tora (1989) etc. Currently, Sanskriti Biplav is in publication.

Politics

The Sri Sri Auniati Satra is one of the raj satras or royal satras of the Ahom kingdom. The Ahom kingdom was established in upper Assam after a Tai prince from Mong Mao (present day southeastern China), Chao Lung Sukaphaa, migrated to Assam in 1228. While it remained relatively small for centuries, it suddenly expanded under the rule of king Suhungmung and went on to become the most influential power in the northeast of India. As a result of the expansion, by 1536, the Hindu subjects greatly outnumbered the Ahoms in the kingdom. To gain legitimacy in the Hindu society, the Ahom dynasty underwent Sanskritisation, with Suhungmung adopting the Sanskrit name Swarganarayana.

However, the formal initiation of the Ahom dynasty into Hinduism did not take place till 1648, when Sutamla became the king.[24] Sutamla established the Sri Sri Auniati Satra and took formal initiation under its first Satradhikar Sri Sri Niranjana Deva Goswami, effectively Sanskritising the dynasty. This was a major event in the history of Assam. Sutamla adopted the name Jayadhwaj Singha following this. Following this, the Ahom state was largely lenient towards the satras of the Brahma Sanghati, while continuing the persecution of the satras of other sanghatis. Rudra Singha even provided the position of raj satra to Auniati, Dakhinpat, Garamur and Kuruwabahi and received initiation from the satradhikar of the Sri Sri Auniati Satra, Sri Sri Harideva Goswami, who was the most prominent of the Brahmin satradhikars of the time.[25] Despite this, the relationship was not always cordial. For example, during the reign of Gadadhara Singha, even satras of the Brahma Sanghati faced persecution. Even at other times, the Ahom kings kept patronising Shaktism in opposition to Vaishnavism.[26][27]

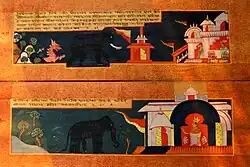

Conservation of manuscripts and artefacts

The satra premises conserve manuscripts and artefacts dating back hundreds of years. These have either been created in the satra itself or gifted by disciples to the satra over the span of several centuries. Almost 150 manuscripts are preserved in the satra's premises, some of which include ankia nats of Srimanta Sankaradeva and Sri Sri Madhavadeva in Brajavali, Adbhut Ramayana by Raghunath Mahanta in old Assamese, Anadi Patan by Sankaradeva in old Assamese, Amara Koshha by Amar Singha in Sanskrit etc.[28]

Several of the artefacts are those gifted by Ahom kings after taking xoron in the satra. A mat of ivory tusks, an inscription with the Srihasta Muktavali translated by Suchananda Oja etc. were gifted by Rudra Singha. He also gifted the plates used by his father Gadadhara Singha to the satra. Gajendra Chintamani, detailing how elephants are caught and tamed, illustrated by Mughal painters Dilbar and Dosai, was gifted by Siva Singha. A musical instrument named Bheri was gifted by Rajeswara Singha. He also gifted a bortaal, a musical instrument weighing 7.5 kilograms. The hendang or sword of Lachit Barphukan is also stored in the satra's museum. The satra has also received gifts from other royalties. The king of Burma Bodofa had gifted Maan Xofura to the then satradhikar Sri Sri Kusharamadeva Goswami, asking his forgiveness, as he was retreating to Burma after the invasion of Assam. Apart from royal gifts, many of the artefacts also include artistic creations by monks themselves. For example, the Rangoli Xorai, Onaroxi Lota etc. Some gifts from disciples include a Naga spear by Naga disciples and Khamti da from Khamti disciples.[29]

Words of wisdom

There are 56 moral verses in assamese inscribed on Goldfish-shaped panels, arranged along the path leading to the Namghar (prayer hall), 28 on each side. The 56 maxims displayed along the path to the Namghar reflect the ethical and spiritual vision of the Assamese saint-scholar Srimanta Sankardev (1449–1568) and the Ekasarana Dharma (Neo-Vaishnavism), which emerged from the broader Shakta–Shaiva–Vaishnava synthesis of medieval Assam. They emphasise selfless service, moral discipline, and the cultivation of vidyā – knowledge understood not merely as intellectual learning, but as transcendent wisdom that leads to liberation (moksha). This knowledge is seen as an inalienable treasure, attained through righteous conduct, self-discipline, and the company of the virtuous, devotion to the Guru, and above all exclusive surrender to Krishna, here referred to as Gobindo Mohaprobhu (“Govinda, the Supreme Lord”), regarded as the ultimate source of liberation. Many of these aphorisms promote altruism, compassion towards all beings, detachment from material greed, and the remembrance of God as the central path to spiritual fulfilment.

- Treat your mother as a goddess, your father as a god, your teacher as a god, and your guest as a god.

- From knowledge comes growth; from growth comes righteousness; from righteousness comes happiness. Therefore, acquire knowledge through effort and study.

- To the narrow-minded, people are divided into “mine” and “others”; to the noble-minded, the whole world is one family.

- Avoid the company of the wicked, seek the company of the virtuous, perform good deeds day and night, and remember always the impermanence of life.

- Righteousness is the wish-fulfilling cow, contentment is the Nandana forest, desire is the river Vaitarani, and knowledge is said to grant liberation.

- The essence of righteousness lies hidden in a cave; the path is that which the great ones have trodden.

- In Kali Yuga, man lies down; in Dvapara, he begins to rise; in Treta, he stands; in Krita, he walks.

- Whatever the best man does, others imitate; the world follows the standard he sets.

- Rivers flow for the benefit of others; cows give milk for the benefit of others.

- A snake is calmed by mantras and medicine; why then can a wicked man not be restrained?

- The hand is adorned by giving, not by bracelets; purity comes from bathing, not sandal paste; satisfaction comes from eating, not merely seeing; peace comes from renunciation, not decoration.

- An elephant is bound by a thousand hands, a horse by a hundred, and a wicked man by simply being sent away.

- All this belongs to the Lord; enjoy what is given, and covet not another’s wealth.

- Even if a crow’s beak is made of gold, its wings inlaid with jewels, and its feet studded with pearls, it is still not a royal swan.

- Of what use is scripture to one without understanding, just as a mirror is useless to the blind?

- The jewel of knowledge is the greatest wealth—it is neither stolen by thieves nor diminished by giving nor divided among relatives.

- Even if Mount Meru moves and the seven seas dry up, a steadfast seeker never swerves from his goal.

- However much sugar you heap on a neem tree, however much milk you pour on it daily, its bitterness will not become sweetness.

- Pamper your child for the first five years, discipline him for the next ten, and when he turns sixteen, treat him as a friend.

- The moon adorns the night, a husband adorns a woman, a king adorns the earth, and learning adorns a gentleman.

- Shun a friend who speaks sweetly to your face but works against you behind your back—like milk poisoned by a snake’s fang.

- Even small things, when united, can accomplish great tasks; a rope made of small strands can bind a mad elephant.

- As fragrance is in the flower, oil in the sesame seed, fire in wood, sugar in sugarcane—so in the body, seek the self through discrimination.

- In righteous conduct resides Lakshmi (fortune); in righteous conduct resides Saraswati (learning); all gods dwell in righteous conduct, and in unrighteous conduct is downfall.

- The tongue of the wise may slip, the foot of the elephant may slip.

- Even Bhima may be broken in battle; even sages may lose their judgment.

- One good tree with fragrant flowers scents the whole forest; likewise, one good son ennobles the whole family.

- As water enters the ground through a spade, so knowledge from the teacher enters the disciple through service.

- A well-refined untruth may seem sweeter than truth and even fit for the gods; hence it is called “the divine speech.”

- A learned man and a king are never equal—the king is honored in his own land, the learned everywhere.

- The father is heaven, the father is dharma, the father is the supreme austerity; when the father is pleased, all gods are pleased.

- Lakshmi dwells in trade, half in agriculture, and half in royal service—never in begging.

- From knowledge comes wisdom; from wisdom comes righteousness; from righteousness comes happiness. Therefore, acquire knowledge through effort and study.

- Milk to a serpent is only a binding of poison; advice to a fool causes anger, not peace.

- Learning is a friend in exile, a mother is a friend at home, medicine is a friend in sickness, righteousness is a friend after death.

- Trees bear fruit for the benefit of others; this body exists for the benefit of others.

- Avoid a wicked man even if learned—like a snake with jewels, he is still dangerous.

- The wise give away wealth for others’ benefit while alive; better to give for a cause than to lose it in destruction.

- There is no mother equal to forgiveness, no wealth equal to fame.

- One’s own dharma, even if imperfect, is better than another’s dharma well performed; dying in one’s own dharma is better, for another’s dharma is dangerous.

- Words without truth do not shine; a man without wisdom does not shine.

- A flower without fragrance does not please; a face without teeth does not please.

- All sins, such as killing a Brahmin, reside in food on the day of Hari’s worship.

- The poison of the Takshaka snake is in its fangs, of the fly in its head, of the scorpion in its tail, but the wicked have poison throughout their body.

- In the three ages, truth, knowledge, and renunciation were means to liberation; in Kali Yuga, only devotion to Brahman leads to it.

- Negligence causes loss of work, loss of growth, poverty, begging, loss of honor, and total ruin by evil deeds.

- Scholars have all virtues but only faults in speech; thus among a thousand speakers, one wise man is distinguished.

- Knowledge gives humility; from humility comes worthiness; from worthiness, wealth; from wealth, righteousness; from righteousness, happiness.

- There is no friend like knowledge, no enemy like disease, no love like that for a child, and no power greater than fate.

- There is no holy place like the Ganga, no mother like one’s own, no guru like one’s own.

- A true friend stands by you in festivals, in misfortune, in famine, in political upheaval, at the king’s gate, and at the cremation ground.

- The jewel of knowledge is not divided among relatives, stolen by thieves, or diminished by giving—it is the greatest treasure.

- The faithful, devoted, and self-controlled attain knowledge; through knowledge, they quickly reach supreme peace.

- One cannot act for the dead, just as one cannot reverse death; mourning the departed is futile—so say the knowers of the Veda.

- Nothing is as pure as knowledge; through self-discipline, in time one realizes it within oneself.

- The gift of ten million cows, the observance of a month at Prayag in Magha, the gift of gold equal to Mount Meru—none equal the utterance of the name of Govinda.

References

- ^ https://auniati.org/about.php

- ^ a b c d e f "Sri Sri Auniati Satra". Official Website of the Majuli District. Retrieved October 24, 2023.

- ^ Kakoti, Keshav (2018). Sri Sri Auniati Xotror Ruprekha (in Assamese) (2nd ed.). Majuli: A. K. Publications. p. 3.

- ^ a b c Kakoti, Keshav (2018). Sri Sri Auniati Xotror Ruprekha (in Assamese) (2nd ed.). A. K. Publications. p. 2.

- ^ a b c d e "Auniati Satra". Assam Info. Retrieved October 24, 2023.

- ^ a b Sarma, Tirthanath. (1975) Auniati Satrar Buronji. (In Assamese). Majuli: Auniati Satra.

- ^ Bhuyan, Suryya Kumar (1960). Satsari Assam Buranji (in Assamese). Guwahati: Gauhati University.

- ^ a b c d Saharia, Diplina (2021). "The Interplay of State and Religion in the Brahmaputra Valley from 16th to the 18th Centuries" (PDF). Journal of Northeast India Studies. 11 (2): 1–16.

- ^ a b Shin, Jae-Eun (2017), "Transition of Satra from a Venue of Bhakti Movement to the Orthodox Brahmanical Institution", in Ota, Nobuhiro (ed.), Clustering and Connections in Pre-Modern South Asian Society, Tokyo: Tokyo University of Foreign Studies, pp. 248

- ^ Barpujari, HK (1992). Barpujari, H K (ed.). The Comprehensive History of Assam. Vol. 2. Guwahati: Publication Board Assam. pp. 263.

- ^ Bhuyan, S. K. (1968). Tungkhungia Buranji or the History of Assam 1681-1806 A.D. Guwahati: DHAS. pp. 32–33.

- ^ Bhuyan, S.K. ed. (1962). Asam Buranji : A history of Assam from the commencement of the Ahom rule to the British occupation in 1826. Guwahati : DHAS.

- ^ Sharma, Chandan Kumar (1996). "Socio-Economic Structure and Peasant Revolt : The Case of Moamoria Upsurge in the Eighteenth Century Assam". Indian Anthropologist. 26 (2): 33–52. JSTOR 41919803. pp. 47.

- ^ Kakoti, Keshav (2018). Sri Sri Auniati Xotror Ruprekha (in Assamese) (2nd ed.). Majuli: A. K. Publications. pp. 3–4.

- ^ "Sri Sri Auniati Satra | Past Satradhikar". www.auniati.org. Retrieved 2023-10-25.

- ^ Kakoti, Keshav (2018). Sri Sri Auniati Xotror Ruprekha (in Assamese) (2nd ed.). Majuli: A. K. Publications. p. 6.

- ^ Nath, Puja; Barua, Upala (2022). "The Importance of Satra and Namghar in the Greater Assamese Society: An Appraisal". Antrocom Online Journal of Anthropology. 18 (2): 671–676.

- ^ a b Kakoti, Keshav (2018). Sri Sri Auniati Xotror Ruprekha (in Assamese) (2nd ed.). A. K. Publications. pp. 6–7.

- ^ Bishnupriya Dutt; Urmimala Sarkar Munsi (2010). Engendering Performance: Indian Women Performers in Search of an Identity. SAGE Publications. p. 216. ISBN 978-81-321-0612-8.

- ^ Frank Burch Brown (2013). The Oxford Handbook of Religion and the Arts. Oxford University Press. pp. 195–196. ISBN 978-0-19-972103-0., Quote: All of the dances considered to be part of the Indian classical canon (Bharata Natyam, Chhau, Kathak, Kathakali, Kuchipudi, Manipuri, Mohiniattam, Odissi, Sattriya, and Yakshagana) trace their roots to religious practices (...) the Indian diaspora has led to the translocation of Hindu dances to Europe, North America and the world."

- ^ a b Kakoti, Keshav (2018). Sri Sri Auniati Xotror Ruprekha (in Assamese) (2nd ed.). A. K. Publications. pp. 13–14.

- ^ a b c Kakoti, Keshav (2018). Sri Sri Auniati Xotror Ruprekha (in Assamese) (2nd ed.). Majuli: A. K. Publications. pp. 15–16.

- ^ Mahotsav, Amrit. "Assam Bilasini and the Freedom Movement". Azadi Ka Amrit Mahotsav, Ministry of Culture, Government of India. Retrieved 2023-10-25.

- ^ Guha, Amalendu (December 1983), "The Ahom Political System: An Enquiry into the State Formation Process in Medieval Assam (1228–1714)", Social Scientist, 11 (12): 21–22, doi:10.2307/3516963, JSTOR 3516963 "The Ahom kings also began to assume Hindu names in addition to their Tai patronymics It was from the days of Pratap Simha again, that they started patronising Hindu temples with land grants. Their formal conversion to Hinduism did not however take place before 1648 and the new attachment became stable only towards the end of the century."

- ^ Gogoi, Lila (1986). The Buranjis, Historical Literature of Assam. the University of Michigan: Omsons Publications.

- ^ Baruah, S.L. (1985), A Comprehensive History of Assam, Munshiram Manoharlal. pp. 294.

- ^ Dutta, Sristidhar (1985), The Mataks and their Kingdom, Allahabad: Chugh Publications. pp. 88.

- ^ Kakoti, Keshav (2018). Sri Sri Auniati Xotror Ruprekha (in Assamese) (2nd ed.). Majuli: A. K. Publications. pp. 38–50.

- ^ Kakoti, Keshav (2018). Sri Sri Auniati Xotror Ruprekha (in Assamese) (2nd ed.). Majuli: A. K. Publications. pp. 28–37.