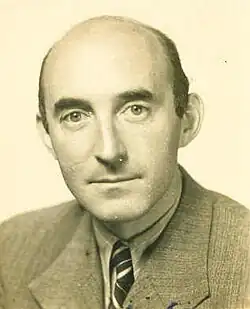

Arnold Buchthal

Arnold Buchthal (born 28 November 1900 in Dortmund, Germany; died 5 August 1965 in Pesaro, Italy) was a German lawyer, a translator at the Nuremberg trials and a State's attorney in Frankfurt.

Early life and education

Arnold Buchthal was the son of Rosa and Felix Buchthal. His mother was the first woman in the Dortmund city council, while his father ran a coffee import and roasting facility with some branches in the city. Arnold grew up in a home built by his parents at Bornstraße 19 which included coffee roasting facilities. He graduated from high school in 1918, having attended the Municipal Gymnasium. In 1923, as part of his law studies, he became a trainee at the Higher Regional Court in Hamm and in 1924 he moved to Dortmund district court. He spoke five languages.[1]

Career

He became a district and county magistrate with an annual salary of 7800 Reichsmark.[1] With the seizure of power by the National Socialists in January 1933, within a few months all Jewish citizens in civil servant positions were dismissed. Arnold Buchthal, son of Jewish parents, "full Jew" in Nazi jargon, was one of them. He received his dismissal from the Prussian Ministry of Justice on July 7, 1933. He and his wife Grete (Margaret)[2] could barely pay for the medical delivery costs of their second daughter (the businesswoman and philanthropist Vera “Steve” Shirley) in September 1933.

The family emigrated to Austria at the end of 1933. After the annexation of Austria by the German Reich in 1938, Jews were no longer safe there. To save the lives of their daughters Renate and Vera, the Buchthals sent them on a Kindertransport from Vienna to England in 1939. Renate (b. 1929) emigrated to Australia later in life. Vera became one of England's most successful entrepreneurs in the 1970s, having changed her name to Stephanie. She was named Dame Stephanie in 2000 and a Companion of Honour in 2018.

Second World War

Arnold Buchthal and his wife Grete (née Schick) who had been born in Krems, Austria, separated. The main reason for the discord was Grete's accusation of having to suffer as a non-Jew from his political problems. Arnold Buchthal emigrated to Switzerland and little later to England. Like all male adults who fled Nazi Germany, he was considered an "enemy alien". The British immigration authorities deported him to Australia in 1940 – along with some 2,000 Jewish refugees and 400 German and Italian prisoners of war. He was sent to the prison camp in Hay, New South Wales. Only a debate in the British Parliament ensured that the survivors of that incarceration came back to England.

From 1941, on Arnold Buchthal was part of an auxiliary team of British troops.

Postwar

After the World War II, Buchthal transferred to the US Army and was employed as a translator to the Nuremberg war crimes trials. Among other things, he had to explain to the US judges words like "Polnisches Untermenschentum", a racist term in Nazi language.

Arnold Buchthal moved to Offenbach and went into the civil service. Until October 1957, he was senior prosecutor of the Frankfurt district court. In this function, he had to deal with the pending case against the Nazi war criminals Adolf Eichmann and his deputy Hermann Krumey. Buchthal cooperated in this matter with his colleague Fritz Bauer, who was the Attorney General of Hesse, and the driving force in organising the Frankfurt Auschwitz trials. Buchthal also received criticism; as prosecutor he acted rashly against a controversial election campaign ad published in several newspapers in 1957.[3] As a result he was transferred as Senate President at the Higher Regional Court to Darmstadt.

Buchthal died in Italy in 1965.

References

- ^ a b Stephanie., Shirley (2012). Let it go : the entrepreneur turned ardent philanthropist. Askwith, Richard. Luton: Andrews. ISBN 9781782342823. OCLC 819521713.

- ^ Ferry, Georgina (2025-08-11). "Dame Stephanie Shirley obituary". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2025-08-12.

- ^ Bär, Fred G. (2003-01-01). "Meusch, Matthias, Von der Diktatur zur Demokratie. Fritz Bauer und die Aufarbeitung der NS-Verbrechen in Hessen (1956–1968)". Zeitschrift der Savigny-Stiftung für Rechtsgeschichte: Germanistische Abteilung. 120 (1): i–ii. doi:10.1515/zrgga.2003.120.1.fm. ISSN 0323-4045.