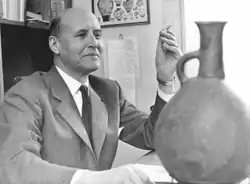

Arne Furumark

Arne Furumark | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Josef Arne Gerdt Furumark 26 September 1903 Kristiania, Sweden–Norway[a] |

| Died | 8 October 1982 (aged 79) Uppsala, Sweden |

| Nationality | Swedish[1] |

| Academic background | |

| Education | Uppsala University |

| Thesis | Studies in Aegean Decorative Art: Antecedent and Sources of the Mycenaean Ceramic Decoration |

| Academic work | |

| Discipline | Archaeology |

| Sub-discipline | Bronze Age Aegean civilisation |

| Institutions | Uppsala University |

| Notable works | The Mycenaean Pottery |

| Signature | |

Josef Arne Gerdt Furumark (26 September 1903 – 8 October 1982) was a Swedish archaeologist who specialised in the ceramics of Mycenaean Greece. His three-volume work The Mycenaean Pottery established a categorisation and chronology of the ceramics of the Late Bronze Age on the Greek mainland. A 1943 review credited him with doing "for Mycenaean pottery what Payne did for Corinthian and Beazley for Attic wares",[2] and subsequent scholars have considered the work a standard reference, though it received criticism for an over-rigid approach and for prioritising stylistic analysis at the expense of information about objects' archaeological contexts.

Furumark was born in the Norwegian capital of Kristiania (now Oslo).[a] After an unhappy childhood, in which he initially seemed set to follow his father into the paper business, he entered Uppsala University in Sweden in 1925 to study the humanities, and became a pupil of the archaeologist Axel W. Persson. He obtained his doctorate, with a thesis on the decoration of Mycenaean ceramics, in 1939, and became an associate professor at Uppsala in the same year. He led excavations at Sinda on Cyprus, the first Swedish archaeological work on the island since the Second World War, between 1947 and 1948, and became a professor at Uppsala in 1952. He remained there until his retirement in 1970, and served a year's term as director of the Swedish Institute at Athens, a research centre for classical archaeology, between 1956 and 1957. He also conducted excavations at San Giovenale in Italy between 1962 and 1963, and published on the Mycenaean settlement of the island of Rhodes.

Although an early sceptic of the idea that the Linear B script was used to write Greek, Furumark corresponded with Michael Ventris, who deciphered it in 1953, and was one of the first archaeologists to use his conclusion that the language was indeed Greek. Furumark's work on ceramics helped to establish the distinctive nature of mainland Greek ("Helladic") ceramics in relation to Cretan ("Minoan") wares, and highlighted the ways in which both cultural groups influenced each other to varying extents over time. In doing so, he helped to overturn the narrative of Arthur Evans that Minoan Crete had dominated mainland Greece throughout the Late Bronze Age. He also established continuity between Mycenaean pottery and that of the following Protogeometric period, and thereby that narratives which argued for the complete overturning of Greek culture at the end of the Bronze Age, such as that of the Dorian invasion, were incorrect.

Biography

Josef Arne Gerdt Furumark was born on 26 September 1903,[3] in the Norwegian capital of Kristiania (now Oslo),[4][a] where his father worked as a businessman in the paper industry.[6] He suffered from a skin condition throughout his life, which left him shy and socially isolated.[7] Family life during his early years was unhappy; Furumark initially attended business school in Norway and worked in his father's offices in Oslo and in London, where at the age of nineteen he visited the British Museum. He later said that this visit encouraged him to change his studies to archaeology. In 1925, he entered Sweden's Uppsala University, where he studied a wide humanities curriculum including classical archaeology, philosophy and theology. He eventually came to study there under the Mycenaean archaeologist Axel W. Persson,[6] under whom he took part in excavations in Greece.[8]

Furumark received his doctorate, with a dissertation on the subject of Mycenaean ceramic decoration, in 1939. In the same year, he was made an associate professor at Uppsala.[8] In 1941, he published The Mycenaean Pottery: Analysis and Classification and The Chronology of Mycenaean Pottery,[9] a two-volume study which analysed, categorised and dated Late Bronze Age ceramics from the mainland of Greece according to their shapes and decorative motifs.[10] He had begun writing a third volume, Mycenaean Pottery: A History, by 1941, but abandoned the project by 1944.[11] He published Det äldsta Italien, a handbook of Italian archaeology, in 1947, which became widely cited: he planned, but never published, an edition in English.[12]

Between 1947 and 1948, Furumark excavated at Sinda on Cyprus.[9] Swedish archaeologists had excavated widely on the island before the Second World War, but Furumark's was the first Swedish project there after 1945.[13] The excavation was conducted in two campaigns; the first from 22 December 1947 to 22 January 1948, and the second from 25 March to 7 May 1948.[14] Carl-Gustaf Styrenius later credited Furumark's excavations with expanding scholarly knowledge of migration from Greece to Cyprus at the end of the Bronze Age.[15] The project uncovered a Late Cypriot (c. 1300 – c. 1200 BCE) settlement with Cyclopean walls,[16] though only excavated a small fraction of its total area of around 46,500 square metres (11.5 acres).[17]

In 1950, Furumark argued, on the basis of the ceramics of Minoan Crete, that the idea of the Cretan site of Knossos being ruled by Greek-speakers in the Late Minoan II period (c. 1490 – c. 1430 BCE) was "untenable":[18] the fact of mainland rule over Crete in this period was established two years later by the discovery by Michael Ventris that the Linear B tablets made there at this time were written in a form of Greek.[19] Furumark had maintained a correspondence with Ventris since 1951;[20] after Ventris proposed his decipherment, Furumark worked with Gudmund Björck, the professor of Greek at Uppsala, to check its accuracy. The two wrote to Ventris in October 1952 to give their verdict that he was correct.[21][b] Furumark was one of the first archaeologists to use his decipherment in his own work.[23][c] Also in 1950, he argued that Mycenaean settlers had arrived on the island of Rhodes around the turn of the Late Helladic IIB and IIIA periods (that is, c. 1400 BCE), that they lived peacefully alongside the pre-existing population, who used Minoan pottery, and were allowed to live in existing houses. Mario Benzi, in 1988, called this idea "astonishing", and suggested that the Mycenaean incomers more probably subjugated the inhabitants by force.[25]

Furumark became Professor of Classical Archaeology and Ancient History at Uppsala University in 1952,[26] succeeding Persson.[27] In the early years of his professorship, he was involved in reorganising the university's collection of antiquities,[8] and created a small museum in two of the university's rooms.[28] He served as director of the Swedish Institute at Athens, a research centre for classical archaeology, between 1956 and 1957.[1] Among his students at Uppsala were Margareta Lindgren, who worked on Linear B,[29] and Gisela Walberg, who extended his work on Mycenaean ceramics to those of Middle Minoan Crete,[30] as well as Sture Brunnsåker and Carl Nylander.[28] His own academic work during his professorship, in contrast to his previous studies of Mycenaean and Italian archaeology, focused on the ancient Aegean scripts.[31] In 1956, he gave a lecture in Berlin in which he attempted to decipher the Linear A tablets uncovered at the site of Hagia Triada on Crete,[32] using the methods applied by Ventris to Linear B,[33] and posited that Linear A had similarities with the Anatolian Indo-European language of Luwian.[32][d] He was appointed a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1958.[35] Between 1962 and 1963, he excavated at San Giovenale in Italy,[9] continuing excavations begun there in the 1950s by the Swedish Institute in Rome.[36] After recovering from a period of serious illness in the late 1960s,[8] he retired from his professorship in 1970,[26] and was succeeded by his former student Sture Brunnsåker.[28] He died on 8 October 1982 in Uppsala.[3]

Contributions to archaeology

Johannes Siapkas, in 2022, identified Furumark as part of a Swedish tradition, traceable back to the work of Erik Hedén at the turn of the twentieth century, to distinguish the academic treatment of the ancient world from the popular understanding of it, and to prioritise scientific objectivity in its reconstruction.[37] A 1943 review of Mycenaean Pottery credited him with doing "for Mycenaean pottery what Payne did for Corinthian and Beazley for Attic wares";[2] Siapkas compared his work with that of Johann Joachim Winckelmann on ancient sculpture.[38]

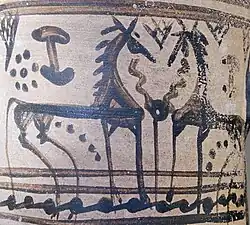

The Mycenaean Pottery was the first complete survey of its subject published in book form,[10] and became the established point of departure for subsequent studies.[38] Furumark's approach developed from that of German stylistic analysis, known as Strukturforschung ('Structural Research'), first practised in the 1920s by archaeologists such as Friedrich Matz.[e] However, Furumark rejected the association made in Strukturforschung, under the influence of Nazi racial theories, between cultural styles and biological races.[40] As well as ceramic vessels, he named and categorised the terracotta figurines known as psi, phi, and tau types.[41] The archaeologist Robin Hägg described the books as Furumark's "magnum opus ... [and] ever since the standard work on this topic";[9] Linda Medwid called them "the definitive reference on the subject" in 2000.[42] Although the absolute dates of Furumark's chronology have generally been revised, the categories and reference he assigned to particular shapes and motifs remain conventional vocabulary within the field.[43]

Furumark's contemporary Alan Wace criticised him for what he called "excessive pigeonholing" of ceramic styles, and for ignoring information about the archaeological contexts in which finds were unearthed; the latter criticism was also articulated by Wace's collaborator Carl Blegen.[38] Susan Sherratt, in 2021, criticised Furumark's approach as "essentially stylistically based and unrealistically over-analytical", particularly by contrast with that of Lisa French, who worked on Mycenaean pottery in the second half of the twentieth century.[44] Gerald Cadogan described Furumark's approach as dirigiste for what he considered its excessive devotion to ordered categorisation.[45][f] In 2011, Sherratt criticised Furumark's system for lumping together variations of shape and motif into single categories, on the basis of what he considered to be evolutionary relationships between them.[43] She also disagreed with his treatment of individual motifs and shapes in isolation, rather than as part of coherent decorative schemes.[47]

Influence on Minoan and Mycenaean studies

Furumark argued that the ceramics of the Mycenaean civilisation of mainland Greece were a development of pre-Mycenaean mainland forms, with influence from contemporary Minoan Crete.[3] This aligned with the view set forth by Wace and Blegen in 1918, that the civilisation of mainland Greece had been broadly continuous and indigenous throughout the Bronze Age. This view, known as the "Helladic Heresy" ("Helladic" meaning "native to mainland Greece"),[48] was itself an extension of the archaeological theory of Christos Tsountas, who argued for the continuity of Greek culture from prehistory to the modern period.[49] Furumark established the sub-periods of the Helladic chronology based on the stages of development of pottery styles, which became the standard relative chronology system used in studies of the Mycenaean period.[10]

Furumark's findings contradicted the idea of Arthur Evans, who had named Minoan civilisation in the early 20th century, that Mycenaean civilisation had developed from that of Crete.[50] Furumark concluded that the level of Minoan influence in mainland ceramics changed over time, with an overall balance roughly even between Cretan- and indigenous-derived vessel shapes, a high level of Cretan influence in the Late Helladic IIIA period (c. 1400 – c. 1300 BCE), and a dominant mainland influence in the following Late Helladic IIIIB period (c. 1300 – c. 1180 BCE).[51] He therefore rejected both the term "Late Minoan", used for mainland pottery of the Late Bronze Age by Evans and Duncan Mackenzie,[10] and Wace and Blegen's "Helladic", which he considered to imply that developments on the mainland were isolated from the wider Aegean. Since Furumark's work, the terms "Helladic" and "Mycenaean" have been considered equivalent,[42] though his belief that "Helladic" did not adequately encompass the influence of Crete and the other Aegean islands has generally been rejected by other scholars.[10]

Medwid called The Mycenaean Pottery "a final refutation" of Evans's view that Mycenaean Greece had been subordinate to Minoan Crete, referencing Furumark's demonstration of the continuity of Mycenaean pottery as well as that certain Mycenaean forms, such as the kylix, were adopted on Crete.[42] Following the 1938 work of Mogens B. Mackeprang,[52] Furumark included two styles of pottery, found by Wace at Mycenae and labelled by him the Granary Style and the Close Style, in his categorisation of the Late Helladic IIIC period (c. 1180 – c. 1050 BCE).[53] He identified a trend in the later part of the period towards simple geometric designs,[10] establishing continuity between Mycenaean pottery and that of the following Protogeometric period, and thereby that narratives which argued for complete cultural collapse or replacement at the end of the Bronze Age, such as that of the Dorian invasion, were incorrect.[42]

Published works

- Furumark, Arne (1939). Studies in Aegean Decorative Art: Antecedent and Sources of the Mycenaean Ceramic Decoration (PhD thesis). Uppsala University.

- — (1941). The Mycenaean Pottery: Analysis and Classification. Stockholm: Kungl. Vitterhets Historie och Antikvitets Adademien. OCLC 1227892574.

- — (1941). The Chronology of Mycenaean Pottery. Stockholm: Kungl. Vitterhets Historie och Antikvitets Adademien. OCLC 3384221.

- — (1947). Det äldsta Italien [Ancient Italy] (in Swedish). Uppsala: J. A. Lindblads Förlag. OCLC 38499170.

- — (1950). Några metod- och principfrågor inom arkeologien [Some Issues of Method and Principle in Archaeology] (in Swedish). Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell. OL 59624098M.

- — (1950). The Settlement at Ialysos and Aegean History c. 1550–1400 BC. Opuscula Archaeologica. Vol. 6. Lund: W. K. Gleerup. OCLC 483356129.

- — (1954). "Ägäische Texte in griechischer Sprache" [Aegean Texts in the Greek Language]. Eranos (in German). 52: 17–60. ISSN 2004-6332.

- — (1961). Redan de gamla grekerna [Already the Ancient Greeks] (in Swedish). Stockholm: Bonniers. OL 59624068M.

- — (1962). Hellener och barbarer [Hellenes and Barbarians] (in Swedish). Stockholm: Bonniers. OL 59624080M.

- — (1976). The Linear A Tablets from Hagia Triada Structure and Function. Lectiones Boethianae. Vol. 3. Stockholm: Paul Åströms förlag. OCLC 878691851.

- — (1992). Aström, Paul; Hägg, Robin; Walberg, Gisela (eds.). Mycenaean Pottery: The Plates. Stockholm: Astrom Editions. ISBN 9-17-916026-3.

- — (2003) [1951]. "Furumark's's Introduction to the 1951 Report". Swedish Excavations at Sinda, Cyprus: Excavations Conducted by Arne Furumark 1947–1948. By Furumark, Arne; Adelman, Charles. Stockholm: Paul Åströms Forlag. pp. 13–16. ISBN 91-7916-046-8.

- —; Adelman, Charles (2003). Swedish Excavations at Sinda, Cyprus: Excavations Conducted by Arne Furumark 1947–1948. Stockholm: Paul Åströms Forlag. ISBN 91-7916-046-8.

Footnotes

Explanatory notes

- ^ a b c Until 1905, Norway was in a personal union with Sweden.[5]

- ^ After Ventris's death in a car accident in 1956, Furumark wrote his obituary in the Swedish newspaper Dagens Nyheter, in which he called his death "an infinitely painful loss [of a] genius [and] shy young man".[22]

- ^ Furumark later suggested that the Linear B script may have been developed on the Greek mainland during the Shaft Grave period (c. 1675 – c. 1500 BCE).[24]

- ^ A manuscript on Linear A and Minoan religion was unpublished at the time of his death.[34]

- ^ According to Furumark's student and biographer, Carl Nylander, he used to say that his only two teachers were Matz and the philosopher Axel Hägerström.[8] Matz praised The Mycenaean Pottery, writing that "Swedish archaeology, which has recently flourished, can be proud of an achievement such as this".[39]

- ^ According to Jan Bouzek, who met Furumark, the latter intended his scheme to be used as a guideline rather than as a "fixed grid"; Bouzek criticised "the dogmatic interpretation of stylistic guidelines by less inspired followers [which] often turns a wise theory into a caricature".[46]

References

- ^ a b Accorinti 2014, p. 323, n. 3.

- ^ a b Daniel 1943, p. 252.

- ^ a b c Medwid 2000, p. 112.

- ^ "Folkräkningar (Sveriges befolkning) 1930" [Census (Sweden's Population) 1930] (in Swedish). National Archives of Sweden. Retrieved 20 July 2025.

- ^ Douglas-Scott 2023, p. 361.

- ^ a b Nylander 1983, p. 34.

- ^ Nylander 1983, p. 38.

- ^ a b c d e Nylander 1983, p. 35.

- ^ a b c d Hägg 1996, p. 476.

- ^ a b c d e f McDonald & Thomas 1990, p. 300.

- ^ Siapkas 2018, p. 14.

- ^ Brunnsaker 1976, p. 30.

- ^ Styrenius 1994, pp. 8–12.

- ^ Furumark 2003, p. 63.

- ^ Styrenius 1994, p. 12.

- ^ Göransson 2012, p. 419.

- ^ Iacovou 2007, p. 10.

- ^ For the dates, see Shelmerdine 2008, p. 5.

- ^ McDonald & Thomas 1990, p. 314.

- ^ Hedlund 2003, p. 10.

- ^ Hedlund 2003, p. 11.

- ^ Hedlund 2003, p. 12.

- ^ "Furumark, Arne". Dictionary of Art Historians. Retrieved 30 June 2025.

- ^ Mylonas 1956, p. 277.

- ^ Benzi 1988, p. 59.

- ^ a b Hägg 1996, p. 476; Medwid 2000, p. 112.

- ^ Åström 2003, p. 7.

- ^ a b c Brunnsaker 1976, p. 31.

- ^ Nosch & Enegren 2017, p. xxviii.

- ^ Hood 1978, p. 375.

- ^ Brunnsaker 1976, pp. 30–31.

- ^ a b MacKendrick 1981, p. 120.

- ^ Braidwood & Mason 1958, p. 59.

- ^ Nylander 1983, p. 37.

- ^ Pohl 1958, p. 412.

- ^ Karlsson 2006, p. 22.

- ^ Siapkas 2022, p. 114.

- ^ a b c Siapkas 2018, p. 7.

- ^ Matz 1943, p. 242.

- ^ Siapkas 2018, p. 15.

- ^ French 1971, p. 103.

- ^ a b c d Medwid 2000, p. 113.

- ^ a b Sherratt 2011, p. 258.

- ^ Sherratt 2021.

- ^ Cadogan 2003, p. 353.

- ^ Bouzek 1994, p. 218.

- ^ Sherratt 2011, p. 259.

- ^ Wace & Blegen 1918, pp. 118–119; Galanakis 2007, p. 241.

- ^ Pliatsika 2020, p. 292.

- ^ Medwid 2000, p. 113; Galanakis 2007, p. 240.

- ^ McDonald & Thomas 1990, p. 301. For the dates, see Shelmerdine 2008, p. 4.

- ^ French 1969, p. 133; see Mackeprang 1938.

- ^ For the dates, see Shelmerdine 2008, p. 4

Works cited

- Accorinti, Domenico (2014). Raffaele Pettazzoni and Herbert Jennings Rose, Correspondence 1927–1958. Texts and Sources in the History of Religion. Vol. 146. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-26684-1.

- Åström, Paul (2003). Foreword. Swedish Excavations at Sinda, Cyprus: Excavations Conducted by Arne Furumark 1947–1948. By Furumark, Arne; Adelman, Charles. Stockholm: Paul Åströms Forlag. pp. 7–8. ISBN 91-7916-046-8.

- Benzi, Mario (1988). "Mycenaean Rhodes: A Summary". In Dietz, Søren; Papachristodoulou, Ioannis (eds.). Archaeology in the Dodecanese. Copenhagen: National Museum of Denmark. pp. 59–72. ISBN 87-480-0626-2.

- Bouzek, Jan (1994). "Late Bronze Age Greece and the Balkans: A Review of the Present Picture". The Annual of the British School at Athens. 89: 217–234. doi:10.1017/S0068245400015380. ISSN 0068-2454. JSTOR 30102571.

- Braidwood, Robert J.; Mason, J. Alden (1958). "Archaeological News". Archaeology. 11 (1): 57–63. ISSN 1943-5746. JSTOR 41666489.

- Brunnsaker, Sture (1976). "Classical Archaeology and Ancient hIstory". Uppsala University. 500 Years: History, Art and Philosophy. Uppsala University. pp. 19–33.

- Cadogan, Gerald (2003). "Obituary: Mervyn Reddaway Popham 1937–2000" (PDF). Proceedings of the British Academy. 120: 345–361. ISSN 0068-1202.

- Daniel, John Franklin (1943). "Review: The Chronology of Mycenaean Pottery and The Mycenean Pottery: Analysis and Classification by Arne Furumark". American Journal of Archaeology. 47 (2): 252–254. doi:10.2307/499815. ISSN 0002-9114. JSTOR 499815.

- Douglas-Scott, Sionaidh (2023). Brexit, Union, and Disunion: The Evolution of British Constitutional Unsettlement. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-84178-8.

- French, Elizabeth (1969). "The First Phase of LH IIIC". Archäologischer Anzeiger [Archaeological Gazette]. 2: 133–138. doi:10.1515/9783112314449-004. ISBN 978-3-11-230326-9. ISSN 2510-4713 – via De Gruyter Brill.

- French, Elizabeth (1971). "The Development of Mycenaean Terracotta Figurines". The Annual of the British School at Athens. 66: 101–187. doi:10.1017/S0068245400019146. JSTOR 30103231. S2CID 194064357.

- Galanakis, Yannis (2007). "The Construction of the Aegisthus Tholos Tomb at Mycenae and the 'Helladic Heresy'". The Annual of the British School at Athens. 102: 239–256. doi:10.1017/S0068245400021481. ISSN 0068-2454. JSTOR 30245251. S2CID 162590402.

- Göransson, Kristian (2012). "The Swedish Cyprus Expedition, The Cyprus Collections in Stockholm and the Swedish Excavations after the SCE". Cahiers du Centre d'Études Chypriotes. 42: 399–421. doi:10.3406/cchyp.2012.1033. ISSN 2647-7300.

- Hägg, Robin (1996). "Furmark, Arne (1903–82)". In de Grummond, Nancy (ed.). An Encyclopaedia of the History of Classical Archaeology. Abingdon: Routledge. p. 476. ISBN 1-884964-80-X.

- Hedlund, Ragnar (2003). "'Bomben i brevlådan': Arne Furumark, Michael Ventris och dechiffreringen av Linear B" ["Bombs in Briefcases": Arne Furumark, Michael Ventris and the Decipherment of Linear B]. Hellenika (in Swedish). 106: 10–12. ISSN 0348-0100.

- Hood, Sinclair (1978). "Review: Kamares: A Study of the Character of Palatial Middle Minoan Pottery by Gisela Walberg". The Classical Review. 28 (2): 375–376. ISSN 0009-840X. JSTOR 3062350.

- Iacovou, Maria (2007). "Site Size Estimates and the Diversity Factor in Late Cypriot Settlement Histories". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 348: 1–23. doi:10.1086/BASOR25067035. ISSN 2161-8062. JSTOR 25067035.

- Karlsson, Lars (2006). San Giovenale: Results of the Excavations Conducted by the Swedish Institute of Classical Studies at Rome and the Sopritendenza alle antichità dell'Etruria Meridionale. Vol. 4. Stockholm: Swedish Institute at Rome. ISBN 91-7042-172-2.

- MacKendrick, Paul Lachlan (1981). The Greek Stones Speak: The Story of Archaeology in Greek Lands. New York: Norton. OCLC 1035307015 – via Internet Archive.

- Mackeprang, Mogens B. (1938). "Late Mycenaean Vases". American Journal of Archaeology. 42 (4): 537–559. doi:10.2307/499186. ISSN 0002-9114. JSTOR i221842.

- Matz, Friedrich (1943). "Review: The Mycenaean Pottery by Arne Furumark". Gnomon (in German). 19 (5): 225–242. ISSN 0017-1417. JSTOR 27676989.

- McDonald, William; Thomas, Carol G. (1990) [1967]. Progress into the Past: The Rediscovery of Mycenaean Civilisation (2nd ed.). Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-33627-9.

- Medwid, Linda M. (2000). "Arne Furumark". The Makers of Classical Archaeology: A Reference Work. Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 112–114. ISBN 1-57392-826-7 – via Internet Archive.

- Mylonas, George (1956). "Mycenaean Greek and Minoan–Mycenaean Relations". Archaeology. 9 (4): 273–279. ISSN 0003-8113. JSTOR 41663417.

- Nosch, Marie Louise; Enegren, Hedvig Landenius (2017). "Preface and Acknowledgements". In Nosch, Marie Louise; Enegren, Hedvig Landenius (eds.). Aegean Scripts: Proceedings of the 14th International Colloquium on Mycenaean Studies, Copenhagen, 2-5 September 2015. Rome: Istituto di Studi sul Mediterraneo Antico. pp. xxvii–xxix. ISBN 978-88-8080-275-4.

- Nylander, Carl (1983). "Furumark, Arne". Kungl. Vitterhets Historie och Antikvitets Akademiens Årsbok 1983 [Royal Academy of Literature, History and Antiquities Yearbook 1983] (in Swedish). Stockholm: Kungl. Vitterhets Historie och Antikvitets Akademien. pp. 34–39. ISBN 91-7402-123-0.

- Pliatsika, Vassiliki (2020). "Journal Pages from the Archaeological Life of Christos Tsountas at Mycenae". In Lagogianni-Georgakarakos, Maria; Koutsogiannis, Thodoris (eds.). These Are What We Fought For: Antiquities and the Greek War of Independence. Athens: Archaeological Resources Fund. pp. 290–305. ISBN 978-960-386-441-7.

- Pohl, Alfred (1958). "Personalnachrichten" [Personnel News]. Orientalia (in German). 27 (4): 412–421. ISSN 0030-5367. JSTOR 43079471.

- Shelmerdine, Cynthia (2008). "Introduction: Background, Methods and Sources". In Shelmerdine, Cynthia (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Aegean Bronze Age. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–18.

- Sherratt, Susan (2011). "Learning to Learn from Bronze Age Pots: A Perspective on Forty Years of Aegean Ceramic Studies in the Work of J. B. Rutter". In Gauß, Walter; Lindblom, Michael; Smith, R. Angus K.; Wright, James C. (eds.). Our Cups Are Full: Pottery and Society in the Aegean Bronze Age: Papers Presented to Jeremy B. Rutter on the Occasion of his 65th Birthday. BAR International Series. Vol. 2227. Oxford: Archaeopress. pp. 257–266. ISBN 978-1-4073-0785-5 – via Academia.edu.

- Sherratt, Susan (22 July 2021). "Lisa French Obituary". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 July 2025.

- Siapkas, Johannes (2018). "Negotiated Positivism: The Disregarded Epistemology of Arne Furumark". Journal of Archaeology and Ancient History. 22: 1–21. ISSN 2001-1199 – via ResearchGate.net.

- Siapkas, Johannes (2022). "Contested Classicism: Reconciling Classical Studies in Twentieth-Century Sweden". In Ekström, Anders; Gustafsson, Hampus Östh (eds.). The Humanities and the Modern Politics of Knowledge: The Impact and Organization of the Humanities in Sweden, 1850–2020. Studies in the History of Knowledge. Amsterdam University Press. pp. 105–128. doi:10.2307/j.ctv2svjznh. ISBN 978-94-6372-886-7.

- Styrenius, Carl-Gustav (1994). "From the Swedish Cyprus Expedition to the Medelhavsmuseet of Today". In Rystedt, Eva (ed.). The Swedish Cyprus Expedition: The Living Past. Stockholm: Museum of Mediterranean and Near Eastern Antiquities. ISBN 91-7192-939-8.

- Wace, Alan; Blegen, Carl (1918). "The Pre-Mycenaean Pottery of the Mainland". The Annual of the British School at Athens. 22: 175–189. doi:10.1017/S0068245400009916. S2CID 163842512. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

External links

- Westin Tikkanen, Karen (ed.). "Arne Furumark's correspondence". Researchdata.se. Retrieved 30 June 2025.