Archaeocyatha

| Archaeocyatha Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Porifera |

| Clade: | † Vologdin, 1937 |

| Synonyms | |

| |

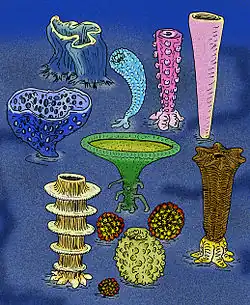

Archaeocyatha (/ˈɑːrkioʊsaɪəθə/, "ancient cups") is a taxon of extinct, sessile, reef-building[a] marine sponges that lived in warm tropical and subtropical waters during the Cambrian Period. It is thought that the centre of the Archaeocyatha origin is now located in East Siberia, where they are first known from the beginning of the Tommotian Age of the Cambrian, 525 million years ago (mya).In other regions of the world, they appeared much later, during the Atdabanian, and quickly diversified into over a hundred families. They became the planet's first reef-building animals and are an index fossil for the Lower Cambrian worldwide.

Preservation

The remains of Archaeocyatha are mostly preserved as carbonate structures in a limestone matrix. This means that the fossils cannot be chemically or mechanically isolated, save for some specimens that have already eroded out of their matrices, and their morphology has to be determined from thin cuts of the stone in which they were preserved.

Geological history

Today, the archaeocyathan families are recognizable by small but consistent differences in their fossilized structures: Some archaeocyathans were built like nested bowls, while others were as long as 300mm. Some archaeocyaths were solitary organisms, while others formed colonies. In the beginning of the Toyonian Age around 516 mya, the archaeocyaths went into a sharp decline. Almost all species became extinct by the Middle Cambrian, with the final-known species, Antarcticocyathus webberi, disappearing just prior to the end of the Cambrian period.[3] Their rapid decline and disappearance coincided with a rapid diversification of the Demosponges. As for the earliest archaeocyathan, the Ediacaran sponge Arimasia from the Nama Group may be within the clade and specifically allied with Monocyathea; however, this is unclear.[2]

The archaeocyathans became the planet's first reef-building animals and are an index fossil for the Lower Cambrian worldwide.[4] for the Lower Cambrian worldwide. were important reef-builders in the early to middle Cambrian, with reefs (and indeed any accumulation of carbonates) becoming very rare after the group's extinction until the diversification of new taxa of coral reef-builders in the Ordovician.[5]

Antarcticocyathus was considered the only late Cambrian archaeocyath, but its reinterpretation as a lithisid sponge[6] means that there are no archaeocyaths identified post the mid-Cambrian.

Morphology

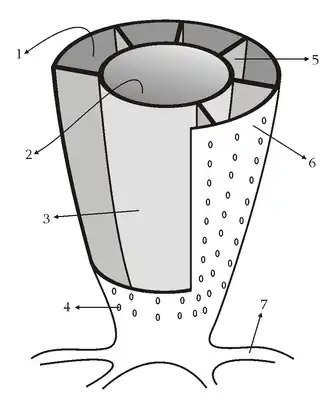

The typical archaeocyathid resembled a hollow horn coral. Each had a conical or vase-shaped porous skeleton of calcite similar to that of a sponge. The structure appeared like a pair of perforated, nested ice cream cones. Their skeletons consisted of either a single porous wall (Monocyathida), or more commonly as two concentric porous walls, an inner and outer wall separated by a space. Inside the inner wall was a cavity (like the inside of an ice cream cup). At the base, these pleosponges were held to the substrate by a holdfast. The body presumably occupied the space between the inner and outer shells (the intervallum).

Ecology

Flow tank experiments suggest that archaeocyathan morphology allowed them to exploit flow gradients, either by passively pumping water through the skeleton, or, as in present-day, extant sponges, by drawing water through the pores, removing nutrients, and expelling spent water and wastes through the pores into the central space.

The size of the pores places a limit on the size of plankton that archaeocyaths could have consumed; different species had different sized pores, the largest large enough to conceivably consume mesozooplankton, possibly giving rise to different ecological niches within a single reef.[7]

Although archaeocyaths have commonly been thought of as stenobionts narrowly adapted to carbonate-dominated marine settings, they were also present in siliciclastic-dominated environments as well.[8]

Distribution

A 2010 study showed that the centre of the Archaeocyatha origin is located in East Siberia, where they are first known from the beginning of the Tommotian Age of the Cambrian, 525 million years ago (mya).[9] In other regions of the world, they appeared much later, during the Atdabanian, and quickly diversified into over a hundred families.

The archaeocyathans inhabited coastal areas of shallow seas. Their widespread distribution over almost the entire Cambrian world, as well as the taxonomic diversity of the species, might be explained by surmising that, like true sponges, they had a planktonic larval stage that enabled their wide spread.

Taxonomy

Their phylogenetic affiliation has been subject to changing interpretations, yet the consensus is growing that the archaeocyath was indeed a kind of sponge,[10] thus sometimes called a pleosponge. But some invertebrate paleontologists have placed them in an extinct, separate phylum, known appropriately as the Archaeocyatha.[11] However, one cladistic analysis[12] suggests that Archaeocyatha is a clade nested within the phylum Porifera (better known as the true sponges).

True archaeocyathans coexisted with other enigmatic sponge-like animals. Radiocyatha and Cribricyatha were two diverse Cambrian classes comparable to Archaeocyatha, alongside genera such as Boyarinovicyathus, Proarchaeocyathus, Acanthinocyathus, and Osadchiites.[13]

The clade Archaeocyatha have traditionally been divided into Regulares and Irregulares (Rowland, 2001):

- Putapacyathida Vologdin, 1961—incertae sedis

- Regulares

- Monocyathida Okulitch 1935

- Capsulocyathida Zhuravleva 1964

- Ajacicyathida Bedford 1939

- Irregulares

- Thalassocyathida

- Archaeocyathida

- Kazakhstanicyathida Konyushkov 1967

However, Okulitch (1955), who at the time regarded the archaeocyathans as outside of Porifera, divided the phylum in three classes:

- Phylum Archaeocyatha Vologdin, 1937

- Class Monocyathea Okulitch, 1943

- Class Archaeocyathea Okulitch, 1943

- Class Anthocyathea Okulitch, 1943

Notable fossil sites

_18.jpg)

The Ajax Mine Fossil Reef in the Flinders Ranges of South Australia contains a large number of Lower Cambrian Archaeocyath fossils, exposed in limestone at ground level.[14] The term "Ajax limestone" is now used worldwide, and this site has been state-heritage-listed as a place of palaeontological and geological significance. The site contains a sample of almost every species of archaeocyatha known to have existed within the Australian-Antarctic geologic province. Its diversity is much greater than any other assemblage in the province, and it also contains over 100 type species, which include over 40 type species from the Cambrian period.[15][16] As of 2022 the fossil site is also one of seven sites in the Flinders Ranges under consideration for UNESCO World Heritage status.[14]

Footnotes

- ^ Archaeocyathid reef structures ("bioherms"), although not as massive as later coral reefs, might have been as deep as 10 m (33 ft) (Emiliani 1992:451).

References

- ^ Wang, Qi; Dai, Qiaokun; Vayda, Prescott; Luo, Jinzhou; Shao, Tiequan; Liu, Yunhuan; Hua, Hong; Xiao, Shuhai (4 April 2025). "Fortunian archaeocyath sponges acquired biomineralization in the beginning of the Cambrian explosion". Geology. doi:10.1130/G53249.1. ISSN 0091-7613. Retrieved 19 April 2025.

- ^ a b Runnegar, Bruce; Gehling, James G.; Jensen, Sören; Saltzman, Matthew R. (October 2024). "Ediacaran paleobiology and biostratigraphy of the Nama Group, Namibia, with emphasis on the erniettomorphs, tubular and trace fossils, and a new sponge, Arimasia germsi n. gen. n. sp". Journal of Paleontology. 98 (S94): 1–59. Bibcode:2024JPal...98S...1R. doi:10.1017/jpa.2023.81.

- ^ The last-recorded archaeocyathan is a single species from the late (upper) Cambrian of Antarctica.

- ^ Anderson, Dr. John R. "Paleozoic Life". Georgia Perimeter College. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 6 July 2010.

- ^ Munnecke, A.; Calner, M.; Harper, D. A. T.; Servais, T. (2010). "Ordovician and Silurian sea-water chemistry, sea level, and climate: A synopsis". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 296 (3–4): 389–413. Bibcode:2010PPP...296..389M. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2010.08.001.

- ^ Lee, Jeong-Hyun (2022). "Limiting the known range of archaeocyath to the middle Cambrian: Antarcticocyathus webersi Debrenne et al. 1984 is a lithistid sponge". Historical Biology. 36: 1–5. doi:10.1080/08912963.2022.2155818. S2CID 254628199.

- ^ Antcliffe, Jonathan B.; Jessop, William; Daley, Allison C. (2019). "Prey fractionation in the Archaeocyatha and its implication for the ecology of the first animal reef systems". Paleobiology. 45 (4): 652–675. Bibcode:2019Pbio...45..652A. doi:10.1017/pab.2019.32. S2CID 208555519.

- ^ Yang, Aihua; Luo, Cui; Han, Jian; Zhuravlev, Andrey Yu.; Reitner, Joachim; Sun, Haijing; Zeng, Han; Zhao, Fangchen; Hu, Shixue (1 November 2024). "Niche expansion of archaeocyaths during their palaeogeographic migration: Evidence from the Chengjiang Biota". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 653: 112419. Bibcode:2024PPP...65312419Y. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2024.112419. Retrieved 15 November 2024 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

- ^ Maloof, A.C. (2010). "Constraints on early Cambrian carbon cycling from the duration of the Nemakit-Daldynian–Tommotian boundary $$\delta$$13C shift, Morocco". Geology. 38 (7): 623–626. Bibcode:2010Geo....38..623M. doi:10.1130/G30726.1. S2CID 128842533.

- ^ Scuba divers have discovered living calcareous sponges, including one species that -- like the archaeocyathans -- is without spicules, thus morphologically similar to the archaeocyaths. Rowland, S.M. (2001). "Archaeocyatha: A history of phylogenetic interpretation". Journal of Paleontology. 75 (6): 1065–1078. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2001)075<1065:AAHOPI>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Debrenne, F. and J. Vacelet. 1984. "Archaeocyatha: Is the sponge model consistent with their structural organization?" in Palaeontographica Americana, 54:pp358-369.

- ^ J. Reitner. 1990. "Polyphyletic origin of the 'Sphinctozoans'", in Rutzler, K. (ed.), New Perspectives in Sponge Biology: Proceedings of the Third International Conference on the Biology of Sponges (Woods Hole) pp. 33–42. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC.

- ^ Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology Part E, Revised. Porifera, Volumes 4 & 5: Hypercalcified Porifera, Paleozoic Stromatoporoidea & Archaeocyatha, liii + 1223 p., 665 figs., 2015, available here. ISBN 978-0-9903621-2-8.

- ^ a b "Ajax Limestone Archaeocyath fossils". Flinders Ranges Field Naturalists. 29 July 2022. Retrieved 3 August 2025.

- ^ "[Ajax Mine Fossil Reef], Zinc Mine Road PUTTAPA". SA Heritage Places database search. Government of South Australia. 2 February 2017. Archived from the original on 3 August 2025. Retrieved 3 August 2025.

Text may have been copied from this source, which is available under a Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) licence. (See here.

Text may have been copied from this source, which is available under a Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) licence. (See here.

- ^ South Australian Heritage Council (8 August 2014). "Summary of state heritage place: Ajax Mine Fossil Reef PLACE NO.: 26390" (PDF). pp. 1–12. Retrieved 3 August 2025.

Further reading

- Emiliani, Cesare. (1992). Planet Earth : Cosmology, Geology, & the Evolution of Life & the Environment. Cambridge University Press. (Paperback Edition ISBN 0-521-40949-7), p 451

- Okulitch, V. J., 1955: "Part E – Archaeocyatha and Porifera. Archaeocyatha, E1-E20", in Moore, R. C., (ed.) 1955: Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology. Geological Society of America & University of Kansas Press, Lawrence, Kansas, 1955, xviii-E122.

External links

- Archaeocyatha - A knowledge base

- Archaeocyathans (UCMP Berkeley)

- Archaeocyatha (Palaeos Invertebrates)

- Three Cambrian Archaeocyatha fossls in limestone in Brachina Gorge, Flinders Ranges, South Australia