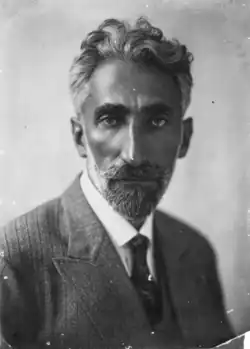

Antin Krushelnytskyi

Antin Krushelnytskyi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Native name | Антін Крушельницький |

| Born | 23 July 1878 Łańcut, Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, Austria-Hungary |

| Died | 3 November 1937 (aged 59) Sandarmokh, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Occupation | writer and pedagogue |

| Nationality | Ukrainian |

| Alma mater | Lviv University |

| Literary movement | Modernism |

| Years active | 1899-1934 |

| Spouse | Mariya Sloboda |

| Children | Ivan, Taras, Bohdan, Ostap, Volodymyra |

Antin Krushelnytskyi (Ukrainian: Антін Крушельницький, born 23 July 1878 in Łańcut, Austria-Hungary - died on 3 November 1937 in Sandarmokh, Soviet Russia) was a Ukrainian writer, pedagogue, political and civic activist, who served as Minister of Education of Ukraine for a short period in 1919. His decision to evade persecution in the Second Polish Republic by emigrating to the Soviet Union ended in tragedy and turned the whole Krushelnytskyi family into symbolic figures of the Executed Renaissance.

Biography

Early career

Born in Łańcut, Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria (now in Poland), Antin Krushelnytskyi spent his early years in Przemyśl, where his father, a lawyer by profession, was an active participant in the Ukrainian cultural community. After finishing the gymnasium, Antin enrolled into Lviv University, where he studied philosophy and wrote his thesis under the mentorship of Mykhailo Hrushevsky. During that time he joined the student organization Young Ukraine and became a member of the Ukrainian Radical Party. Some of Krushelnytskyi's early works were positively evaluated by the party's leader Ivan Franko, who promoted their publication.[1]

After finishing his studies, Krushelnytskyi worked as a teacher in various towns of Galicia. Starting from 1908 he was a member of pedagogical societies active in the region and took part in publishing of school literature dedicated to the teaching of Ukrainian language. His schoolbooks, which included works by Taras Shevchenko and other Dnieper Ukrainian authors, as well as elements of folk literature, were positively evaluated by critics. Before the beginning of the First World War Krushelnytskyi headed the Ukrainian gymnasium in Horodenka, where he worked on promoting access of the Ukrainian youth to education and supported the activities of Prosvita, Sich, Sokil and other civic organizations.[1]

Work in the Ukrainian government, emigration and return

After the proclamation of the West Ukrainian People's Republic in 1918, Krushelnytskyi was one of the most loyal supporters of its president Yevhen Petrushevych as member of the Ukrainian National Council. After the Unification Act he entered the government of the Ukrainian People's Republic, serving as the Minister of Education. However, after less than three months Krushelnytskyi resigned due to a conflict with Symon Petliura and emigrated to Vienna, where he established a Ukrainian publishing house. Soon thereafter Krushelnytskyi moved to Uzhhorod, the capital of Czechoslovak-ruled Carpathian Ruthenia, and managed a gymnasium there. Observing the developments in Soviet-occupied Ukraine, he was enthusiastic about the ongoing Ukrainization campaign organized there. Unknowingly to Krushelnytskyi, in 1921 Soviet secret services had issued a death warrant on him as an "enemy of the people".[1]

In 1925 Krushelnytskyi returned to Polish-ruled Galicia and worked as the director of a Ukrainian gymnasium in Rohatyn, where he actively introduced new pedagogical methods and ideas, among others founding a female branch of Plast. However, in 1926 he had to resign due to a conflict with the Ukrainian Pedagogical Society and moved first to Yavoriv, and finally to Kolomyia, where he directed a Jewish gymnasium. Krushelnytskyi eventually moved to Lviv, where he headed a teachers' seminary and gymnasium. However, his progressive ideas were opposed by the conservative public of Galicia, which forced him to end his teaching career in 1927. From that time he worked as a journalist, publicist and editor.[1]

Move to the Soviet Union, imprisonment and death

By the late 1920s Krushelnytskyi had become an active supporter of Bolshevism, adopting "Soviet nationalist" ideas. He maintained close contacts with the Soviet consulate in Lviv and used his publication New Ways (Ukrainian: Нові шляхи, 1929-1932) to promote the Sovietization of Eastern Galicia. In 1932 the newspaper was banned, and Krushelnytskyi himself arrested and imprisoned for three months.[1] This event failed to discourage him from supporting pro-Bolshevik positions, and until 1933 he edited another Sovietophile publication - Krytyka.[2] During that period the Krushelnytskyi family were close to publicist Yaroslav Halan, a fellow sympathizer of the Soviet Union. Krushelnytskyi himself publicly denied the truthfulness of reports about the Holodomor famine in Soviet Ukraine, which turned him into one of the targets of a planned assassination attempt by the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN). However, the plan failed after Mykola Lemyk, who had been tasked with the murder, killed a consulate worker instead.[1]

In 1934, hoping to start cultural work in Soviet Ukraine, Antin Krushelnytskyi left Lviv and moved to Kharkiv together with his wife, two sons, a daughter-in-law and a granddaughter. There they were joined by Volodymyra and Ivan, who had moved to the city earlier, and were followed by Taras and his wife Stefania. The family settled in the Slovo Building. Antin adopted Soviet citizenship and was hired as an editor of the Ukrainian Soviet Encyclopedia. However, in the night of 6 November 1934, Antin, Ivan and Taras were arrested. On 15 December the same fate awaited Bohdan, Ostap and Volodymyra. Antin himself was accused of maintaining ties with the OUN. According to the court sentence issued on 28 March 1935, he and fellow Galician Yulian Bachynsky had allegedly created an "underground counterrevolutionary nationalist organization" which supposedly prepared terror attacks against Soviet party leadership.[1]

Sentenced to ten years of imprisonment, Antin Krushelnytskyi served his term in Solovki prison camp. Having learnt of his the execution of his two sons, he declared a hunger strike and reportedly suffered from psychiatric problems. On 9 October 1937 Antin, Bohdan and Ostap were sentenced to death by the NKVD troika of Leningrad Oblast. On 3 November they were executed at Sandarmokh in Karelia together with other Solovki prisoners.[1]

The execution of Krushelnytskyi family shocked the Ukrainian community of Galicia and put an end to Sovietophile ideas among the region's intellectual elite. Literary works dedicated to the family's tragedy were created by contemporary authors Oleksandr Oles and Bohdan-Ihor Antonych.[1]

Personal life

Krushelnytskyi was married to Galician actress and activist Mariya Sloboda. The family had 5 children: sons Ivan, Taras, Bohdan and Ostap, as well as daughter Volodymyra. Ivan, the oldest son, followed his father's steps by studying philosophy at Vienna University, learned five languages and published his own works. In 1929 he was arrested by Polish authorities on the accusation of keeping banned literature. Next year Taras was also imprisoned after being implicated in ties with the Ukrainian Military Organization. Ivan later moved to Soviet Ukraine and worked at the Institute of Material Culture in Kharkiv, specializing on the art of Western Ukraine. After a court proceeding in Kyiv, on 17 December Ivan and Taras were executed by firing squad in the city's October Palace as part of a group of 28 members of Ukrainian intelligentsia. In 1935 Bohdan, Ostap and Volodymyra were sentenced by NKVD to up to five years of labour camps; the two younger sons would eventually be executed among with their father. The only members of Krushelnytskyi family not to be murdered or exiled by Soviet authorities were Antin's granddaughter Larysa, aged nine at the time of the process, and Taras's wife Stefania, who gave birth to a daughter two weeks after her husband's execution.[1]

Literary works

Krushelnytskyi's prose works were influenced by European modernist trends of the era. He also engaged in literary criticism, created school books and translated works of other authors.

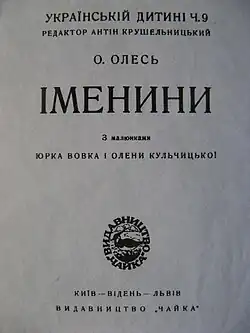

Notable works by Antin Krushelnytskyi:[2]

- Proletarians (Ukrainian: Пролетарі, 1899) - collection of stories

- Semchyshyn Family (Ukrainian: Семчишини, 1901) - drama

- Man of Honour (Ukrainian: Чоловік чести, 1904) - drama

- Eagles (Ukrainian: Орли), 1907) - comedy

- Forest is Being Cut Down (Ukrainian: Рубають ліс, 1918) - novella

- Noise of the Halych Land (Ukrainian: Гомін Галицької Землі, 1918-1919) - novella

- Weekday Bread (Ukrainian: Буденний хліб, 1920) - collection of stories

- When Earth Speaks (Ukrainian: Як промовить земля, 1920) - novella

- When Earth Embraces (Ukrainian: Як пригорне земля, 1920) - novella

- Artiste (Ukrainian: Артистка, 1920) - drama