Allal al-Fassi

Allal al-Fassi | |

|---|---|

علال الفاسي | |

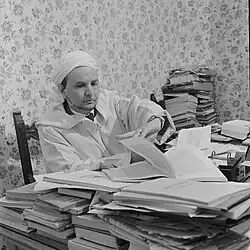

.jpg) Allal al-Fassi in 1949 | |

| Minister of Islamic Affairs | |

| In office 1961–1963 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 10 January 1910 Fes, Morocco |

| Died | May 13, 1974 (aged 64) Bucharest, Romania |

| Political party | Istiqlal |

| Parents | Abd al-Wahid al-Fassi |

| Religious life | |

| Religion | Islam |

| Movement | |

| Alma mater | al-Qarawiyyin University |

Muhammad Allal al-Fassi (Arabic: محمد علال الفاسي, romanized: Muḥammad ʿAllāl al-Fāsī; January 10, 1910 – May 13, 1974) was a Moroccan revolutionary,[2] politician, writer, poet, Pan-Arabist[3] and Islamic scholar[4] who was one of the early leaders of the Moroccan nationalist movement later becoming a leading member of the Istiqlal Party. He was a "neo-Salafist" who advocated for the synthesis of nationalism and Salafism. He developed the idea of Greater Morocco which later came to influence the official policy of Morocco.

He has been described as the "Father of Moroccan Nationalism".[5][6]

Early life and education

Muhammad Allal al-Fassi was born in Fes on 10 January 1910[2] to a prominent Andalusian family claiming descent from Uqba ibn Nafi[7] and a companion of the Islamic prophet Muhammad which produced hundreds of Islamic scholars[2] known as the Fassi Fihri family.[8] His father, Abd al-Wahid al-Fassi,[9] was a judge,[10] grand mufti,[11] doctor of divinity at and curator of the library of Qarawiyyin.[2] Abd al-Wahid was also a merchant who founded the Nasiriyyah Free School in Fes.[12] He served as the imam at the Royal Mosque in Fes and mufti of Fes.[13] Allal al-Fassi's mother came from a prominent mercantile family known as the Ma'safirine family[9] who held considerable influence in Northern Morocco.[2]

At the age of 5, he entered a Quranic school.[14] He memorized the Quran by the age of 7.[15] Before attending Qarawiyyin at the age of 14, Allal al-Fassi was a student in the Nasiriyyah Free School his father founded.[12] Beginning in 1924,[16] he studied at the University of al-Qarawiyyin[17][18] where he received a purely Arab education and came under the influence of the Salafiya movement.[7]

Early nationalist activity

According to al-Fassi, he became politically conscious in 1925 when the French authorities attempted to appropriate water from the Oued Fes to divert it to French companies.[10] When he joined Qarawiyyin, he associated with the older students who started their nationalist activities in 1919.[14] In 1926, he set up a nationalist newsletter called Umm al-Banin.[12][19] In 1927, along with other students at Qarawiyyin, al-Fassi founded the Students' Union which sought the purification of Islam and aimed to alter the teaching methods of the university. It joined with another group, Supporters of Truth, a student group in Rabat led by Ahmed Balafrej, in 1929 to form The Moroccan League.[20] By 1930, al-Fassi began to lecture at mosques, Quranic schools and the Qarawiyyin on the theme of the Prophet and the Rashidun caliphs.[14] Al-Fassi graduated with a degree in Islamic law in 1930[21] or 1932.[14] He used the public lectures and course on the life of the Prophet to express his political views like his disdain for the French Protectorate. This was seen as a threat by the French administration and by 1933, the Resident-General passed a dahir forbidding al-Fassi along with two other Qarawiyyin lecturers from public speaking.[22] He along with his colleagues were removed from their position as ulema at Qarawiyyin.[23]

In response to the Berber Dahir being passed, Allal al-Fassi began to coordinate alongside other nationalists like Ahmed Balafrej[24] and aroused public protest against the dahir. In al-Fassi's view, the dahir was "barbaric" and an "attempt at the annihilation of native people" by suppressing Arab and Islamic culture while replacing it with pre-Islamic Berber customs.[21] He co-founded the first political party in Morocco, the National Action Bloc (Arabic: كتلة العمل الوطني, romanized: Kutlat al-ʿAmal al-Waṭanī; or the Kutla)[10][25] or Moroccan Action Committee[24] (French: Comité d'Action Marocaine; CAM)[26] founded in 1931,[10] 1933[24] or 1934.[14] This party emerged from the protest movement against the Berber Dahir.[27] In February 1934, al-Fassi met with Sultan Mohammed.[28][29] The Kutla published the Plan of Reforms (French: Plan de Réformes marocaines) in 1934 in both Arabic and French.[30] Allal al-Fassi was one of the ten signatories of the reform plan[27] and he took a copy to the Resident-General with Mohammed Diouri.[31] The demands of the reform plan included the abolition of the Berber Dahir, unification of legal systems under Maliki law, expansion of the education system open to Moroccans, the forming of municipal councils, the promotion of Moroccans into positions of power and making Arabic an official language.[29] The reform plan did not outright call for independence but sought reform and the restoring of confidence in the aims of the 1912 Treaty of Fes.[32][33] Allal al-Fassi discussing the reform plan says:

The reform program was an ingenious stratagem to reconcile the existing treaties with the interests of the country, in the economic section, for example, the Kutla advocated the open-door policy and free trade, in accordance with the resolutions of the Algeciras Conference. This platform was designed to appeal to the support of the left-wing parties in France and to the signatories of the Algeciras international conference; at the same time, it was agreeable to the best interests of Morocco under the circumstances.[34]

The plan was rejected by the French administration[35] and by 1937, the nationalist movement started to split.[36] The Kutla split into the National Party (Ḥizb al-Waṭanī) which al-Fassi co-led and the Popular Movement (Ḥaraka Shaʿbiyya) later the The Party of Democracy and Independence (Ḥizb al-Shūrā wa-l-Istiqlāl) which was led by al-Fassi's former ally Mohamed Hassan Ouazzani.[10] Those that followed Allal al-Fassi in the split were often referred to as the Allaliyin, while al-Fassi was referred to as "Shaykh Allal" or "Hajj Allal".[37]

In 1931, he was allowed back to Fes, and he again picked up his political agitations in the city, and started campaigning and giving nationalistic speeches which gathered success and emotions amongst the masses who admired his eloquence. This prompted the French to exile him again in 1933, this time to Geneva where he met the Lebanese political leader Shakib Arslan, and would assist him in his historical works on the Maghreb region. Arslan, already in contact with young Moroccan nationalists in Switzerland such as the future PM Ahmed Balafrej, mentored him in political organization, and introduced him to many political contacts, and also publicized his name in his various journalistic articles and correspondences. Allal came back to Morocco in 1934, and founded the kutlat al-'amal al-watani كتلة العمل الوطني, Comité d'Action Marocaine (CAM) and the first Moroccan-led workers' union in 1936, and in December of that year officially petitioned the French Colonial Residence in Rabat demanding a number of reforms. This led the French authorities to decide to disband and persecute the members of his political organization, and in 1937, exiled him to the small town of Port-Gentil in Gabon where he would remain for the next nine years until 1946, receiving very little information about the affairs of the outside world during that period.

While he was in exile, the CAM was renamed in 1944 as the Istiqlal Party, which became the nationalist party and the driving force after the Moroccan Army of Liberation (Jaysh al-Tahrir).

Istiqlal party and post-independence

He broke with the party in the mid-1950s, siding with armed revolutionaries and urban guerrillas who waged a violent campaign against French rule, whereas most of the nationalist mainstream preferred a diplomatic solution. In 1956, as Morocco gained independence, he reentered the party, and famously presented his case for reclaiming territories that have once been Moroccan in the newspaper al-Alam. In 1959, after the left-wing UNFP split off from Istiqlal, he became head of the party.[38]

From 1961 to 1963, he served briefly as Morocco's Minister of Islamic Affairs.[39] He was elected to the Parliament of Morocco in 1963, and served there as an Istiqlal deputy. He then went on to become a main leader within the opposition during the 1960s and the start of the 1970s, campaigning against King Hassan II's constitutional reforms that ended parliamentary government. He died of a heart attack on 13 May 1974,[40] on a visit to Romania where he was scheduled to meet with Nicolae Ceaușescu.[2]

Views

Arabism

Allal al-Fassi wanted an independent Morocco that was closely linked to Arab culture and the Middle East[41] and he promoted a greater Arab identity.[42] He proposed that the phrase "Arab kingdom" be added to the 1962 constitution but this request was declined by the king.[43] He supported the Arab League.[44]

Salafism

Allal al-Fassi was one of the most prominent Salafists in Morocco[45] and he became influenced by Salafism during his time at al-Qarawiyyin.[7] He advocated for what he called neo-Salafiyya (al-salafiyya al-jadida)[46][47] and belonged to a liberal trend of Salafism.[16] According to scholars Frederic Wehrey and Anouar Boukhars, al-Fassi saw Salafism as "a constructive force that fostered progress and kindled nationalistic revolutionary consciousness".[45] According to al-Fassi, Salafism "was synonymous with nationalism".[16]

Al-Fassi differed greatly from "purist Salafis" who were more similar to Wahhabists from Saudi Arabia and disapproved of his conception of Salafism.[48] Al-Fassi saw Salafism as a movement that meant Islamic revival and his definition of it was so broad that it could include any reformer since the 9th century as long as they affirmed tawhid, advocated for Islamic law, attempted to prevent the decline of the ummah or opposed despotism. This meant, for al-Fassi, that both Ibn Rushd and Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab could be considered Salafis. He wanted students to read the Salafi writings of Rashid Rida and Muhammad Abduh who he claimed influenced the Salafist program of Morocco.[49] Allal al-Fassi has been associated with Islamic modernism.[50][51]

Sharia

Al-Fassi advocated for Sharia to serve as the basis for the Moroccan legal system.[52] He sought the reactivation of ijtihad[53] and was hostile to Maliki law.[45][54] Allal al-Fassi opposed customary law in Morocco which he labelled as jahili, a "pre-Islamic custom" that had to be abolished. He thought it was equally "horrific" to the customs of some African tribes and he believed customary law deprived women of rights that were granted to them by the Sharia like inheritance.[55] In the context of Islamic law, scholar of Islamic studies, Wael Hallaq, places Allal al-Fassi in the camp of legal reformers that he calls the utilitarianists who aimed to stay within limits of traditional Islamic legal theories and methodologies whilst also considering the need to modernise the legal system.[56]

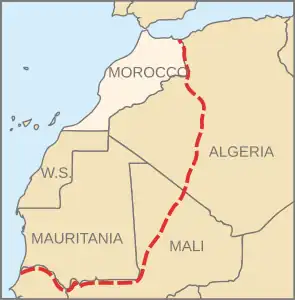

Greater Morocco

Allal al-Fassi was the thinker behind Greater Morocco[59] which he believed was the territories that were historically a part of Morocco[60] before colonialism truncated Morocco's borders. In July 1956, he put forward a map in the Istiqlal newspaper, Al-Alam, which included all of Mauritania, parts of Western Algeria and a section of Northern Mali and all of the Spanish Sahara.[58][59] He did not think the independence of Morocco would be complete without these territories:

... so long as Tangier is not liberated from its international status, so long as the Spanish deserts of the south, the Sahara from Tindouf and Atar and the Algerian-Moroccan borderlands are not liberated from their trusteeship, our independence will remain incomplete and our first duty will be to carry on action to liberate the country and to unify it.[57]

Initially, only a few were interested in Greater Morocco but in part because of Allal al-Fassi's charisma it gradually won over the support of the rest of the Moroccan government.[45]

Women's rights

Allal al-Fassi supported the emancipation of women.[45][61] He called for the ban of polygamy.[62][63] Although, he only opposed polygamy because he thought it tarnished the image of modern Islam rather than it harming women.[64][65] Allal al-Fassi was part of the codification commission of the Mudawana[66] and served as its head.[67][68] Despite this, his liberal ideas on women were not integrated into the Mudawana.[69]

Literature

| Moroccan literature |

|---|

| Moroccan writers |

|

| Forms |

|

| Criticism and awards |

|

| See also |

In 1925, Al-Fassi published his first book of poems. Some of Allal al-Fassi's works include:

- “Munāqashat al-mīzāniyya al-farʿiyya li-wizārat al-ʿadl.” In al-Adāʾ al-barlamānī lil-zaʿīm ʿAllāl al-Fāsī. Rabat: Muʾassasat ʿAllāl al-Fāsī, 2010.[70]

- Rasāʾil tashhad ʿalā l-tarīkh. Rabat: Muʾassasat ʿAllāl al-Fāsī, 2006.[70]

- Al-Ḥarakāt al-Istiqlāliyya fī l-Maghrib al-ʿArabī. Sixth Edition. Casablanca: Muʾassasat ʿAllāl al-Fāsī, 2003.[70]

- Al-Taqrīb: Sharḥ Mudawwanat al-Aḥwāl al-Shakhṣiyya al-kitābān al-awwal wa-l-thānī. Rabat: Muʾassasat ʿAllāl al-Fāsī, 2000.[70]

- Difāʿan ʿan al-Sharīʿa. Second Edition. Beirut: Manshūrāt al-ʿAṣr al-Ḥadīth, 1972.[70]

- “al-Ḥaraka al-Salafiyya fī l-Maghrib.” In Ḥadīth al-Maghrib fī l-Mashriq. Cairo: al-Maṭbaʿa al-ʿĀlamiyya, 1956.[70]

- al-Naqd al-dhati Rabat: Matba'at al-Risala, 1979 (Self Criticism).[72]

Personal life

Both of Allal al-Fassi's daughters were married to leading figures of Moroccan politics; ex-Prime Minister and longtime Istiqlal party Secretary General Abbas El Fassi, and Mohamed El Ouafa ex-Minister and vocal dissident figure within the party.

Despite his support for Arabization and Islam, he educated his children in francophone secular schools. His first-born son became a cardiologist.[73]

See also

References

- ^ Schriber 2024, pp. 351–352

- ^ a b c d e f g Reference Library of Arab America: International Arab figures. Vol. 2. Gale Group. 1999. pp. 25–26. ISBN 978-0-7876-4174-0.

- ^ Haller, Tobias; Käser, Fabian; Ngutu, Mariah (2021-01-06). Does Commons Grabbing Lead to Resilience Grabbing? The Anti-Politics Machine of Neo-Liberal Development and Local Responses. p. 194. ISBN 978-3-03943-839-6.

- ^ Encyclopedia of World Biography, Gale Research Inc, Edition: 2, Published by Gale Research, 1998, ISBN 978-0-7876-2541-2, p. 167

- ^ Reynolds, Guy (2008-01-01). Apostles of Modernity: American Writers in the Age of Development. University of Nebraska Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-8032-1646-4.

- ^ Guerin, Adam (2015-03-15). "'Not a drop for the settlers': reimagining popular protest and anti-colonial nationalism in the Moroccan Protectorate". The Journal of North African Studies. 20 (2): 229. doi:10.1080/13629387.2014.917586. ISSN 1362-9387.

- ^ a b c Bidwell, Robin (2012-10-12). Dictionary Of Modern Arab History. Routledge. pp. 137–138. ISBN 978-1-136-16291-6.

- ^ Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). "al-Fāsī family". Encyclopaedia of Islam (3rd ed.). Brill Online. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_27016. ISSN 1873-9830.

- ^ a b Mogilski 2006, p. 39

- ^ a b c d e Schriber 2024, p. 354

- ^ Howe, Marvine (2005-06-30). Morocco: The Islamist Awakening and Other Challenges. Oxford University Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-19-534698-5.

- ^ a b c Bano, Masooda (2015-03-20). Shaping Global Islamic Discourses. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-1-4744-0348-1.

- ^ Mogilski 2006, p. 40

- ^ a b c d e Johnston 2007, p. 84

- ^ Mohammed, Bek; Zine, Abdallah; Abdesslame, Akkache (2024-12-21). "Moroccan leader Allal El Fassi and the Algerian revolution". Journal for ReAttach Therapy and Developmental Diversities. 7 (6): 492. doi:10.53555/jrtdd.v7i6.3371. ISSN 2589-7799.

- ^ a b c Bruce, Benjamin (2018-08-25). Governing Islam Abroad: Turkish and Moroccan Muslims in Western Europe. Springer. p. 52. ISBN 978-3-319-78664-3.

- ^ Bulutgil, H. Zeynep (2022). The Origins of Secular Institutions: Ideas, Timing, and Organization. Oxford University Press. p. 155. ISBN 978-0-19-759844-3.

- ^ Dwyer, Kevin (2016-03-22). Arab Voices: The human rights debate in the Middle East. Routledge. p. 127. ISBN 978-1-317-24591-9.

- ^ Pennell 2000, p. 206

- ^ Mogilski 2006, p. 42

- ^ a b Mogilski 2006, p. 43

- ^ Mogilski 2006, pp. 45–46

- ^ Ashford 2015, p. 36

- ^ a b c Cabré, Yolanda Aixelà (2018). "Imazighen and Arabs in the Spanish Protectorate : A Review of the Construction on the Contemporary Moroccan Nation". In Cabré, Yolanda Aixelà (ed.). In the Footsteps of Spanish Colonialism in Morocco and Equatorial Guinea: The Handling of Cultural Diversity and the Socio-Political Influence of Transnational Migration. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 51. ISBN 978-3-643-91010-3.

- ^ Fenner, Sofia (2023-07-11). Shouting in a Cage: Political Life After Authoritarian Co-optation in North Africa. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-55750-4.

- ^ Powers, Holiday (2025-01-28). Moroccan Modernism. Ohio University Press. ISBN 978-0-8214-2581-7.

- ^ a b Cabré, Yolanda Aixelà (2018). "Imazighen and Arabs in the Spanish Protectorate : A Review of the Construction on the Contemporary Moroccan Nation". In Cabré, Yolanda Aixelà (ed.). In the Footsteps of Spanish Colonialism in Morocco and Equatorial Guinea: The Handling of Cultural Diversity and the Socio-Political Influence of Transnational Migration. LIT Verlag Münster. pp. 57–58. ISBN 978-3-643-91010-3.

- ^ Pennell 2000, p. 231

- ^ a b Bulutgil, H. Zeynep (2022). The Origins of Secular Institutions: Ideas, Timing, and Organization. Oxford University Press. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-19-759844-3.

- ^ Miller 2013, p. 129

- ^ Pennell 2000, p. 232

- ^ Miller 2013, p. 134. "Strikingly, the Plan did not call for an independent Morocco or separation from France; instead, it aimed at “ restoring confidence in the work of France in Morocco ” and demanded greater Moroccan participation in government, a more cooperative relationship with the Residency, and a more faithful execution of the provisions of the 1912 Treaty of Fez...The decision to work within the framework of the Residency was sincere, for at that moment, the nationalist leadership still did not visualize Morocco without France. But that did not mean a relationship of servility or abuse. At a fundamental level, the Plan launched a frontal assault on the colonial mentality and the corrupt practices it had engendered; namely, the racism, discrimination, and anti-liberalism that allowed Moroccans to be treated as inferiors."

- ^ Wyrtzen 2016, pp. 159–160. "It summarized their reformist agenda, which still accepted and assumed a Franco-Moroccan protectorate framework but appealed to the “protector” to do a better job of fulfilling the mandate of the Treaty of Fes."

- ^ Wyrtzen 2016, p. 160

- ^ Miller 2013, p. 135

- ^ Chenntouf, Tayeb (1993-12-31). "The Horn and North Africa, 1935-45: crises and change". In Mazrui, Ali A.; Wondji, Christophe (eds.). General History of Africa: Africa since 1935. UNESCO Publishing. p. 40. ISBN 978-92-3-102758-1.

- ^ Wyrtzen 2016, p. 151

- ^ "Reflecting on the legacy of 'Allal al-Fassi". Crescent International. Retrieved 2022-02-03.

- ^ Schriber 2024, p. 355

- ^ "Allal el Fassoi, 82, Dead; Top Moroccan Nationalist". The New York Times. 13 May 1974.

- ^ Howe, Marvine (2005-06-30). Morocco: The Islamist Awakening and Other Challenges. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-19-516963-8.

- ^ Gray, Doris H. (2012-11-08). Beyond Feminism and Islamism: Gender and Equality in North Africa. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 215. ISBN 978-0-85772-529-5.

- ^ Aslan, Senem (2015). Nation Building in Turkey and Morocco. Cambridge University Press. p. 109. ISBN 978-1-107-05460-8.

- ^ Pennell 2000, p. 276

- ^ a b c d e Wehrey, Frederic M.; Boukhars, Anouar (2019). Salafism in the Maghreb: Politics, Piety, and Militancy. Oxford University Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-19-094240-3.

- ^ Spadola, Emilio (2018-07-03). "The Call of Communication: Mass Media and Reform in Interwar Morocco". In Eickelman, Dale F. (ed.). Middle Eastern and North African Societies in the Interwar Period. Brill. p. 103. ISBN 978-90-04-36949-8.

- ^ Spadola, Emilio (2013-12-25). The Calls of Islam: Sufis, Islamists, and Mass Mediation in Urban Morocco. Indiana University Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-253-01145-9.

- ^ Lauzière, Henri (2012-08-06). "The Religious Dimension of Islamism Sufism, Salafism, and politics in Morocco". In Shehata, Samer (ed.). Islamist Politics in the Middle East: Movements and Change. Routledge. p. 97. doi:10.4324/9780203126318. ISBN 978-1-136-45536-0.

- ^ Lauzière, Henri (2015-11-17). The Making of Salafism: Islamic Reform in the Twentieth Century. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-54017-9.

- ^ Curtis IV, Edward E. (2012-02-01). Islam in Black America: Identity, Liberation, and Difference in African-American Islamic Thought. State University of New York Press. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-7914-8859-1.

- ^ Sadiqi, Fatima (2025-03-31). Daesh Ideology and Women's Rights in the Maghreb. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-1-3995-3688-2.

- ^ Ayoob, Mohammed (2014-03-26). The Politics of Islamic Reassertion (RLE Politics of Islam). Routledge. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-134-61110-2.

- ^ Cuno, Kenneth M.; Desai, Manisha (2009-12-28). Family, Gender, and Law in a Globalizing Middle East and South Asia. Syracuse University Press. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-8156-5148-2.

- ^ Bruce, Benjamin (2018-08-25). Governing Islam Abroad: Turkish and Moroccan Muslims in Western Europe. Springer. p. 53. ISBN 978-3-319-78664-3.

This suspicion extended even to certain members of the religious establishment and the ulema, in that Allal al-Fassi had shown himself to be hostile to Morocco's Maliki school of jurisprudence, which he saw as an impediment to the use of reason and an obstacle to a more dynamic and engaged understanding of Islam.

- ^ Abaza, Mona (2009-12-04). "'Ada/Custom in the Middle East and Southeast Asia". In Gluck, Carol; Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt (eds.). Words in Motion: Toward a Global Lexicon. Duke University Press. p. 76. doi:10.1215/9780822391104-005. ISBN 978-0-8223-9110-4.

- ^ Mogilski 2006, pp. 56–57

- ^ a b Baers, Michael (2022-10-10). A History of the Western Sahara Conflict: The Paper Desert. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 146–147. ISBN 978-1-5275-8573-7.

- ^ a b Lecocq, Baz (2010-11-15). Disputed Desert: Decolonization, Competing Nationalisms and Tuareg Rebellions in Mali. Brill. p. 62. ISBN 978-90-04-19028-3.

- ^ a b Zunes, Stephen; Mundy, Jacob (2010-08-04). Western Sahara: War, Nationalism, and Conflict Irresolution. Syracuse University Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-8156-5258-8.

- ^ Abourabi, Yousra (2024-05-13). Morocco’s Africa Policy: Role Identity and Power Projection. Brill. pp. 59–60. ISBN 978-90-04-54662-2.

- ^ Sadiqi, Fatima (2003). Women, Gender, and Language in Morocco. Brill. p. 92. ISBN 978-90-04-12853-8.

- ^ Sadiqi, Fatima (2003). Women, Gender, and Language in Morocco. Brill. p. 22. ISBN 978-90-04-12853-8.

- ^ Lamrabet, Asma (2018-05-02). Women and Men in the Qur’ān. Springer International Publishing. p. 27. ISBN 978-3-319-78741-1.

- ^ Ennaji, Moha; Sadiqi, Fatima (2008-02-07). "Morocco: Language, Nationalism, and Gender". In Simpson, Andrew (ed.). Language and National Identity in Africa. Oxford University Press. p. 54. doi:10.1093/oso/9780199286744.003.0003. ISBN 978-0-19-928674-4.

- ^ Sadiqi, Fatima (2013-09-13). "The Central Role of the Family Law in the Moroccan Feminist Movement". In Salhi, Zahia Smail (ed.). Gender and Diversity in the Middle East and North Africa. Routledge. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-317-98907-3. JSTOR 20455613.

- ^ Schriber 2024, p. 351

- ^ Baker, Alison (1998-01-01). Voices of Resistance: Oral Histories of Moroccan Women. SUNY Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-7914-3621-9.

- ^ Salime, Zakia (2009-12-28). "Revisiting the Debate on Family Law In Morocco: Context, Actors and Discourses". In Cuno, Kenneth M.; Desai, Manisha (eds.). Family, Gender, and Law in a Globalizing Middle East and South Asia. Syracuse University Press. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-8156-5148-2.

- ^ Sadiqi, Fatima (2013-09-13). "The Central Role of the Family Law in the Moroccan Feminist Movement". In Salhi, Zahia Smail (ed.). Gender and Diversity in the Middle East and North Africa. Routledge. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-317-98907-3. JSTOR 20455613.

- ^ a b c d e f Schriber 2024, p. 374

- ^ "Allal al-Fassi - Philosophers of the Arabs". www.arabphilosophers.com. Retrieved 2024-11-19.

- ^ Boutieri, Charis (2016-04-18). Learning in Morocco: Language Politics and the Abandoned Educational Dream. Indiana University Press. p. 256. ISBN 978-0-253-02050-5.

- ^ Boutieri, Charis (2016-04-18). Learning in Morocco: Language Politics and the Abandoned Educational Dream. Indiana University Press. pp. 54–55. ISBN 978-0-253-02050-5.

Sources

- Schriber, Ari (2024-11-04). "Allal al-Fassi: Visions of Shariʿa in Post-Colonial Moroccan State Law". In Hashas, Mohammed (ed.). Contemporary Moroccan Thought: On Philosophy, Theology, Society, and Culture. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-51953-4.

- Johnston, David L. (2007-09-17). "ʿAllāl al-Fāsī: Sharīʿa as a Blueprint for Righteous Citizenship". In Amanat, Abbas; Griffel, Frank (eds.). Shari’a: Islamic Law in the Contemporary Context. Stanford University Press. pp. 83–104. ISBN 978-0-8047-5639-6.

- Mogilski, Sara (2006). French influence on a 20th century 'Ālim : 'Allal al-Fāsī and his ideas toward legal reform in Morocco (Thesis). McGill University. Retrieved 13 August 2025.

- Pennell, C. R. (2000). Morocco Since 1830: A History. Hurst. ISBN 978-1-85065-273-1.

- Miller, Susan Gilson (2013-04-15). A History of Modern Morocco. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-81070-8.

- Wyrtzen, Jonathan (2016-01-05). Making Morocco: Colonial Intervention and the Politics of Identity. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1-5017-0425-3.

- Ashford, Douglas Elliott (2015-12-08). Political Change in Morocco. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-7850-5.

Further reading

- El Guabli, Brahim. "Racialization in Exile: Allal al-Fassi's Racial Positionalities in Gabon". Souffles.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Tajdin, Mustapha (2020). "Sharīʿa as State Law: An Analysis of ʿAllāl al-Fāsī's Concept of the Objectives of Islamic Law". Journal of Law and Religion. 35 (3): 494–514. doi:10.1017/jlr.2020.41. ISSN 0748-0814.

- Gaudio, Attilio (1972). Allal El Fassi ou l'Histoire de l'Istiqlal (in French). A. Moreau, 3 bis, quai aux Fleurs.

- Stora, Benjamin; Ellyas, Akram (1999). "EL-FASSI Mohamed Allal:(Maroc, 1910-1974, figure nationale et homme d'État)". Points d'appui (in French): 147–149. ISSN 1275-1561.

- Salih, Hamza (2021-09-30). "Allal Al-Fassi's Utopia: Liberalism and Democracy within the Revivalist System of Thought". International Journal of Language and Literary Studies. 3 (3): 202–215. doi:10.36892/ijlls.v2i3.705. ISSN 2704-7156.

External links

![]() Media related to Allal al-Fassi at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Allal al-Fassi at Wikimedia Commons

- World biography Biography of Mohammed Allal al-Fassi