Albert Pel

Albert Pel | |

|---|---|

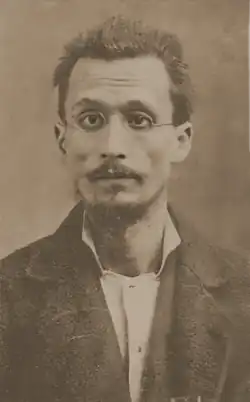

Portrait of Pel by artist Henri Meyer for the newspaper Le Journal illustré, November 2, 1884 | |

| Born | Félix-Albert Pel 12 June 1849 Aigueblanche, Savoie Department, France |

| Died | 9 June 1924 (aged 74) New Caledonia Prison, New Caledonia |

| Other names | "The Watchmaker of Montreuil" |

| Conviction | Murder |

| Criminal penalty | Death; commuted to life imprisonment with hard labour |

| Details | |

| Victims | 1–4 |

Span of crimes | 1872–1884 |

| Country | France |

Date apprehended | July 1884 |

Félix-Albert Pel (12 June 1849 – 9 June 1924) was a French suspected serial killer. He was nicknamed The Watchmaker of Montreuil.

The serial killer Landru was compared to Pel at his own trial because of the many similarities between the two cases.

Youth

Born in Grand-Coeur, in the municipality of Aigueblanche, Albert Pel was the son of a watchmaker and a merchant. His parents separated shortly after his birth, apparently because of adulterous acts committed by his mother. Pel said during his trial he suffered from "doubts that he really was the son of the Savoie watchmaker listed as his father on his birth certificate". He remained with his father in Bourg-Saint-Maurice when his mother moved to Paris. She was remembered for her modest trade of religious objects on Sainte-Croix-de-la-Bretonnerie street. Pel was raised by his father and later taken in by one of his uncles.[1]

In 1859, Pel's uncle, Master Flandin, a lawyer at Moûtiers and took an interest in the boy, proposed to send him to Paris to finish his education and serve an apprenticeship. There, he lived mainly with his mother who entrusted the boy first to the sisters of Saint Augustine, then to the brothers of Saint Nicolas, Vaugirard.

At the age of fifteen he joined MM. Leriel and Maucolin. Three years later he joined the Manceau watchmaking company at 17 Rue La Fayette as a craftsman then moved on to the Josse company at 13 Rue de Douai. Pel lived with his mother on Rue Bleue at this time, but he did not prosper, so they moved to rue de Rochechouart in mid-1869, where Albert opened a watchmaking shop. Miss Reichenbach, a neighbor of the Pels, testified at the trial about Albert's lack of sympathy for his mother.

First murder

In early August 1872, Mrs. Pel was struck by violent abdominal pain. The doctor visited her once, noting pain in her abdomen and stomach, and obstruction in her airways.When she died on August 26, her son didn't seem very upset. According to witnesses, he only exclaimed: “She's gone!” The death certificate listed the cause of death as “chronic bronchitis.” Pel insisted that no one come to sit watch over the body or attend the burial. Neighbors assumed that the strange noises they heard that day was him searching for hidden valuables in the house.

Pell's father died in Bourg Saint-Maurice the next year. Pel had not left Paris and seemed utterly detached from this death. He did return, though, to collect his inheritance of approximately 25,000 francs. The investigation notes that he wore a red ribbon in his buttonhole for the occasion, which intrigued those attending the funeral. When questioned, he replied:

“It's because I'm a big shot in Paris! When you make the trip, be sure to come and attend the course I teach at the Sorbonne.”

First signs of psychic disorders

Pel moved frequently over the next two years. From 1872 to 1874 he presented himself as a mathematics teacher at the Lycée Saint-Louis, as a rhetoric teacher, and as an organist at the Trinity Church. He wore emblems of awards he had not earned. He also told a fellow apprentice, Mr. Hubert, that his mother had been electrocuted by a Ruhmkorff coil he had.[2]

In July 1874, he settled in Rue Raynouard in Passy. Over the next three years his refined demeanor, serious appearance, and hard work ethic had earned him the respect of the neighborhood when an unfortunate event occurred in October 1877. A Mr. Serin, to whom he owed money, apparently very rudely demanded payment of a debt of 2,000 francs. Pel responded at first with threatening letters, then one day went Serin's home and pointed a gun at him. Disarmed and taken to the police commissioner, Pel was jailed. Rambling incoherently, he was quickly taken to the infirmary, where he was examined and diagnosed as delusional. He was placed in Sainte-Anne, where he remained under observation for a month. Upon his release, specialists declared him completely cured, and he paid off his creditor.

First disappearance

On his release he opened a pastry shop, then an advertising agency, and later became manager and sponsor of the Théâtre des Délassements-Comiques. In 1878, he moved to Rue Doudeauville, where he used the name Cuvillier, with the consent of Mme Cuvillier, to protect himself from his creditors. In May 1879, he moved to Rue Doisy in Les Ternes, to an apartment where he devoted himself exclusively to physics and chemistry. He then passed himself off as a physician.

Pel lived with his mistress and Eugénie Meyer, a seamstress in her fifties who mended costumes at the Théâtre de l'Odéon. Also in the home was Marie Mahoin, the maid. Two months later, Meyer and Mahoin both suddenly showed symptoms of vomiting, diarrhea, and unquenchable thirst. Meyer fell ill first. Mahoin cared for her for some time, but then feeling very ill herself, was admitted to Beaujon Hospital on July 19, 1880. She recovered in only eight days, but in the meantime Meyer had disappeared. During this time Pel had lived as a recluse in his home, having his mail passed to him through a transom window. When Miss Mahoin wanted to return, Pel, looking strange, refused to let her into the home. She demanded to at least take the trunk she had left behind, so he asked her to wait a few moments, closed the door, then brought her the belongings. Pel sold Meyer's clothes and jewelery and when he moved out of the apartment, bloodstains were found on the walls.[3] In a corner of the garden, under a pile of manure, the landlord found a bloody carpet.[4] A preliminary investigation was opened to look into Meyer's disappearance. Pel was the main suspect but the case was dismissed for lack of evidence. Pel then moved to Rue Kléber, where he resumed his profession as a watchmaker.

Second wave of deaths

First marriage

On August 26, 1880, Pel married a young saleswoman named Eugénie Buffereau, who worked in a shop on Avenue d'Eylau (now Avenue Victor-Hugo). She brought a dowry of about 4,000 francs to the marriage. A month later, the young woman suffered from continuous vomiting and complained of intense thirst.

On October 21, having received a note from Buffereau saying, “Come quickly if you want to see me alive!” her mother came to visit. Bufferau wanted to eat at the table, but could barely stand and vomited a lot. A doctor, Dr. Raoult, was called and initially suspected mushroom poisoning,[5] but then concluded that it was acute gastroenteritis. Buffereau died on October 24, 1880, to the complete indifference of her husband. Her family, outraged, considered taking legal action before changing their minds for fear of scandal. Bufferau's body was exhumed and examined by experts after Pel was arrested in 1884 and they found a significant amount of arsenic in her remains. He defended himself by claiming that his wife had been taking an arsenic-containing patent medicine called Fowler's solution.[6]

Second marriage

Pel moved again in 1881, settling on Rue du Dôme in Passy. He courted an apprentice he had employed for some time named Angèle Dufaure Murat-Bellisle. After several weeks they announded plans to marry but her family was suspicious. They wanted to draw up a marriage contract to protect her dowry of around 5,000 francs. Pel fiercely opposed this but was willing to agree that after the ceremony he would draw up a will leaving his property to his widow if she and her mother did the same for his benefit.

After the wedding, the Pel couple decided to settle in Nanterre and Mrs. Dufaure-Murat moved in with them. Albert resumed his studies of toxic substances while continuing his profession as a watchmaker. He developed a "Philloxericide by Dr. Pel," supposedly a pesticide that would revolutionize the wine-growing regions. In addition, he obtained authorization from the Paris Police Prefecture to sell poisonous substances and chemicals. Mrs. Dufaure-Murat then began to suffer from abdominal pain. Frightened by the large quantity of dangerous substances in the house, which she attributed to her illness, she eventually moved to Paris and left the young couple alone. Without the ability to kill Madam Dufaure-Murat, killing his wife was pointless.[4] When in April, Angèle abandoned Albert, he let her go. He had begun a relationship with Élise Boehmer, an employee of commercial firms who had brought watches for him to repair. Boehmer had grown up in a convent and had lived a frugal, solitray life, investing her money as the years went by into bonds with Credit Foncier.[4][7]

In Montreuil

On June 21, 1884, Albert and Boehmer moved to Montreuil-sous-Bois, at 9 Rue de l'Église. At some point she had sold all her bonds and given the last of the money to Pel. When she had no more, he began poisoning her.[8] On July 2, she began suffering from abdominal cramps and vomiting that caused her intolerable pain.[9] A Madame Deven and another neighbor came to care for her daily until July 12, when Pel stationed himself at the sick woman's bedside.[7] She died that evening, and nothing of her was ever seen again. Several witnesses reported that during the night Pel had covered the windows with black cloth and rugs. Others complained of a terrible smell coming from the kitchen and claimed to have seen the watchmaker lighting large fires in an oven which did not go out until sunrise.[10] Two neighbors pulled themselves up high enough to peep around the cloth and saw Pel, stripped naked and perspiring, stoking the flames in a stove with a bellows. The next morning Madam Deven climbed up to Boehmer's bedroom window. The bed was empty with the bedding scattered about and through the window she noticed a strong smell of bleach. After a brief investigation, the public prosecutor suspected him of having cremated his girlfriend and ordered his arrest. It is likely that Pel destroyed the remains to prevent forensic identification of arsenic in them.[11] Pel claimed that Boehmer, feeling much better, had left him on July 13 in a carriage that he himself had gone to fetch more than five kilometers away in Faubourg Saint-Antoine. After making inquiries, the police charged Albert Pel with seven counts of poisoning and he was held for trial.

Trial

Pel appeared before the Seine Assize Court on Thursday, June 11, 1885. The trial, presided over by Judge Dubard, lasted three days. The indictment included seven counts poisoning over a period of ten years, but only two were prosecuted (those of Eugénie Buffereau and Élise Boehmer). Albert Pel denied all charges. He pleaded innocence and was represented by a young public defender named Mr. Joly.

Thirty-six years old at the time of his conviction, Pel was, according to newspapers of the time, of average height and frail appearance.[12] His very distinctive features made as much of an impression on people at the time as the originality of his crimes. He combed his black hair upward, his face was thin and sallow, his cheekbones extraordinarily prominent; his eyes hidden behind gold-rimmed glasses; his nose beaked and pointed; his lips thin and discolored. He sported a black mustache and goatee. During the two trials, he appeared dressed in black and wearing a white scarf. The nonchalance journalists often noted in him contrasted with the seriousness of the charges against him. He proclaimed his innocence until the end.

The public prosecutor, Attorney General Bernard, emphasized Pel's greed throughout the trial. The symptoms of all the victims -- stomach cramps, difficulty breathing, nausea, abdominal pain, diarrhea, rapid weakness, convulsions -- are the very distinct characteristics of arsenic poisoning. No fewer than fifty witnesses, including experts, took the stand and explained how Élise Boehmer's remains could have been dismembered and destroyed in the back room of the Montreuil store. In forty hours the stove would have destroyed every last trace of the human body. The evidence against him included the large quantities of ash found at Pel's home, a blood-stained saw, a hatchet and kitchen knife covered in suspicious stains, a cast-iron stove suspected of having been used to incinerate the missing bodies; a book on chemicals and another on poisons, and a staggering quantity of chemicals of all kinds.

On June 13, 1885, after three quarters of an hour of deliberation, the jury declared Pel not guilty of poisoning Eugénie Buffereau, but guilty of the murder of Élise Boehmer. Albert Pel, aged 36, was thus sentenced to death.[13] However, due to a procedural error (one of the jurors was tainted and had not been replaced), the verdict was overturned and the case was referred to the Melun Assize Court. As Pel had been acquitted of the poisoning of Buffereau, he could only be tried for Boehmer's. On August 14, the Seine-et-Marne jury found Pel guilty of poisoning her, but granted him mitigating circumstances. Pel was sentenced to hard labor for life and served his sentence in the New Caledonia penal colony in Bourail.

He died there on 9 June 1924, three days before his seventy-fifth birthday, which made him the oldest convict in France.[14]

See also

Bibliography

- Lecoq (policeman-amateur) (1886). The secret of Pel: novel of a famous cause. Paris. p. 60.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Pel, the poisoning clockmaker: an ancestor of Landru ("Crimes and Punishments" (No. 21) ed.). Paris: The National Bookstore. 1931. p. 32.

- Pierre Bouchardon and Jean Prunière (1934). A forerunner of Landru: The watchmaker Pel (Rainbow ed.). Grenoble: Benjamin Arthaud. p. 117.

- Solange Fasquelle (1976). The Watchmaker of Montreuil (Never admit ed.). Paris: Presses de la Cité. p. 188. ISBN 2-258-00037-8.

- Paul Brouardel (1886). The Pel Affair. Baillière. p. 60.

TV documentaries

- The Mysterious Affair of the Watchmaker Pel, telefilm directed by Pierre Nivollet and broadcast on 28 February 1961 as part of the programme En your soul and conscience.[15]

References

- ^ Paul Brouardel (1886). The Pel Affair. Baillière. p. 6..

- ^ Irving, H. B. (1901). Studies of French Criminals of the Nineteenth Century (PDF). London: William Heineman. p. 257.

- ^ "Pel the poisoner". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. 13 June 1885. p. 6. Retrieved 15 August 2025.

- ^ a b c Chauvaud, Frédéric (2022). Les Tueurs de femmes et l’addiction introuvable (PDF). HAL Open Archive. p. 110.

- ^ "Many Murders Laid at his Door". The Buffalo Daily Republic. 12 June 1885. p. 1. Retrieved 15 August 2025.

- ^ Chast, François (2018). "Les substances vénéneuses en France, 1518-2018". Revue d'Histoire de la Pharmacie. 105 (400): 607–630. doi:10.3406/pharm.2018.23717.

- ^ a b "Pel the poisoner". Harrisburg Daily Independent. 13 June 1885. pp. 3, continues here. Retrieved 15 August 2025.

- ^ "A poisoner of Paris". The Gazette. 13 June 1885. p. 1. Retrieved 15 August 2025.

- ^ Pel, l'horloger empoisonneur : un ancêtre de Landru. 1931.

- ^ Brouardel, Paul (1886). Affaire Pel: accusation d'empoisonnement (in French). Baillière.

- ^ Cage, E. Claire, ed. (2022), "Poisoning and the Problem of Proof", The Science of Proof: Forensic Medicine in Modern France, Studies in Legal History, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 45–78, ISBN 978-1-009-19834-9, retrieved 15 August 2025

- ^ "p1 - Votre recherche - Recherche exacte Liste de résultats Tout "albert pel" : 203 résultats - Gallica". gallica.bnf.fr. Retrieved 13 August 2025.

- ^ "ALBERT PEL". West Australian. 13 August 1885. p. 3. Retrieved 15 August 2025.

- ^ Christophe Hondelatte, "Albert Pel, the big brother of Landru", broadcast by Hondelatte on Europe 1, June 29, 2017, 29 mins. 15 s.

- ^ "En votre âme et conscience - E41 - La Mystérieuse Affaire de l'horloger Pel - Vidéo Ina.fr". ina.fr. Retrieved 28 June 2018.