Aetna Life Insurance Co. v. Lavoie

| Aetna Life Insurance Co. v. Lavoie | |

|---|---|

| |

| Decided April 22, 1986 | |

| Full case name | Aetna Life Insurance Company v. Lavoie |

| Citations | 475 U.S. 813 (more) |

| Argument | Oral argument |

| Holding | |

| The Due Process Clause requires state supreme court justices to recuse themselves from cases in which they have a direct, personal, substantial, and pecuniary interest in the outcome. | |

| Court membership | |

| |

| Case opinion | |

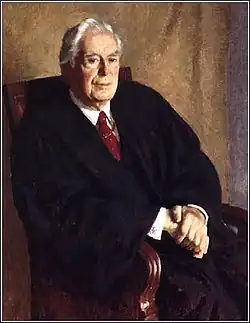

| Majority | Burger, joined by unanimous |

| Stevens took no part in the consideration or decision of the case. | |

Aetna Life Insurance Co. v. Lavoie, 475 U.S. 813 (1986), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court held the Due Process Clause requires state supreme court justices to recuse themselves from cases in which they have a direct, personal, substantial, and pecuniary interest in the outcome.[1][2]

Background

In Winter of 1997, Margaret Lavoie was admitted to a hospital on her physician's recommendation. Mrs. Lavoie remained in the hospital for twenty-three days for various medical tests. After Mrs. Lavoie's discharge, the hospital sent the local Aetna Life Insurance Company office the requisite forms, medical records, and a bill for $3,028.25. The local office paid $1,650.22 of the $3,028.25 hospital bill and sent a letter to the Aetna national office reasoning that Mrs. Lavoie's twenty-three day hospital day was unnecessary.[1]

When Aetna Life Insurance Company refused to pay the full amount of a hospital bill, Margaret and Roger Lavoie (her husband) brought suit in an Alabama state court, seeking both payment of the full amount and punitive damages for the company's alleged bad-faith refusal to pay a valid claim. The jury awarded $3.5 million in punitive damages. The Alabama Supreme Court affirmed, 5 to 4, in a per curiam opinion written by Justice T. Eric Embry.[1]

Aetna then filed an application for rehearing, and, before the application was acted on, learned that, while the case was pending before the Alabama Supreme Court, Justice Embry had filed two actions in an Alabama court against insurance companies alleging bad-faith failure to pay claims and seeking punitive damages. One of the actions was a class action on behalf of all state employees insured under a group plan by Blue Cross-Blue Shield. Aetna then filed a motion challenging, on due process grounds, Justice Embry's participation in the per curiam decision and his continued participation in considering the rehearing application, and also alleging that all justices on the court should recuse themselves because of their interests as potential class members in the Blue Cross suit. The court denied these motions, and also the rehearing application. Two justices wrote separately in the brief order stating that they were taking action to not be included as class members in the Blue-Cross suit.[1]

Approximately two weeks later, Aetna received a copy of Justice Embry's deposition taken in the class action. During the deposition, Justice Embry expressed frustration with insurance companies and that he had issues processing insurance claims for years. After receiving the deposition, Aetna filed another motion for rehearing. After that motion was denied, Aetna filed an appeal to the Supreme Court of the United States.[1]

Subsequently, the Blue-Cross suit was settled, and Justice Embry received $30,000 under that settlement.[1]

Opinion of the court

The court heard oral arguments on December 4, 1985. The court issued its opinion on April 22, 1986. Justice John Paul Stevens took no part in the decision.[1]

Majority Opinion

Chief Justice Warren E. Burger wrote the unanimous 8–0 Majority opinion.[1]

First, the court reasoned that it had jurisdiction because the Alabama Supreme Court reached the merits of Aetna's constitutional challenge and Aetna timely objected.[1]

Proceeding to the merits, the court considered was whether Justice Embry's participation in the case violated the Due Process Clause through various lenses. The common law rule was that judges could not be disqualified for bias or prejudice. In Tumey v. Ohio, the court had previously held that judicial bias was a statutory issue, not a constitutional one. The court had held such a recusal statute constitutional in Patterson v. New York. The court also referenced the American Bar Association's Code of Judicial Conduct, which requires a judge to disqualify themselves for bias or prejudice. However, ultimately the Court declined to address the matter as a Due Process Clause issue because it said Aetna's allegations were not extreme.[1]

Instead, court relied on its prior holding in in re Murchison for the proposition that no judge "can be a judge in his own case [or be] permitted to try cases where he has an interest in the outcome" and is disqualified from presiding over the matter. The Court held that Justice Embry's participation in the case did violate the Fourteenth Amendment because he initiated a similar case that the decisions in the Alabama Supreme Court would be binding on. The Court reasoned that Justice Embry essentially made new law in his decision as he did not apply well-established law in the Alabama Supreme Court. Accordingly, the Court held that Justice Embry was acting as a judge in his own case.[1]

The majority found that Justice Embry did have a direct, personal, substantial, and pecuniary interest in the suit between Aetna and the Lavoies because shortly after his decision in the Alabama Supreme Court, the lawsuit he initiated with similar issues settled out of court and he received $30,000 dollars. However, the Court clarified that it was not required to find that Justice Embry was influenced. The issue was whether there was temptation that would sway the average judge. In addition, the majority noted that the Due Process Clause may bar judges who had no bias or could overlook their bias, but their disqualification is necessary for the appearance of justice.[1]

The court held that the participation of all of the Alabama Supreme Court justices besides Justice Embry did not violate the Due Process Clause. Reasoning that the Justices did not have a direct, personal, substantial, and pecuniary interest in the outcome of the case because there was no evidence or suggestion that the other justices were aware of the class action before deciding the case on its merits.[1]

The Court decided to vacate the lower court's judgment and remand due to Justice Embry's vote being a decisive one vote and the fact that he authored the Alabama Supreme Court's opinion.[1]

Justice Brennan's Concurring Opinion

Justice William J. Brennan Jr. wrote a concurring opinion. He agreed with the majority that Justice Embry's interest in the case and participation violated due process. Additionally, he agreed that Justice Embry should have recused himself.[1]

Justice Brennan wrote separately from the majority to articulate that non-pecuniary interests require recusal. As well as the point that a judge's interest in a case can be direct even if a judge's goal cannot be obtained in that same proceeding.[1]

Justice Brennan also wrote separately to clarify his understanding of the Majority opinion. Stating that even if Justice Embry did not receive the thirty-thousand dollar settlement, he still was disqualified from proceeding over the case. As well as his view that the majority opinion should not be read to suggest that Justice Embry being the deciding vote was outcome determinative. Reasoning that a judge's influence cannot be measured, as judges exchange ideas and arguments that influence one another.[1]

Justice Blackmun's Concurring Opinion

Justice Harry Blackmun wrote a Concurring opinion joined by Justice Thurgood Marshall. He joined the majority opinion's conclusion that Justice Embry's participation in the case violated the Due Process Clause.[1]

Justice Blackmun wrote separately to state that Justice Embry being the deciding vote should be irrelevant to the constitutional violation. Reasoning that Justice Embry's participation in deliberation was enough to violate the Due Process Clause, regardless if he wrote the decision or joined a decision. Justice Blackmun referenced his own experience on the Supreme Court for the proposition that a strong dissent could sway justices to change their vote. He argued that since deliberation between justices is private, a reviewing court may not be able to discover whether bias played a role in the ultimate decision.[1]

Subsequent developments

The matter returned to the Alabama Supreme Court in 1987. The court noted how it was the fourth time it heard the matter. As a result and due to extenuating circumstances, the court decided to make a decision without remanding to the lower court. The Alabama Supreme Court upheld the Trial court's denial of Aetna's Motion for directed verdict and post-trial motion for Judgment notwithstanding verdict. The court conditioned the ruling on Aetna filing a Remittitur of damages.

In Williams v. Pennsylvania, the Supreme Court held that a judge who should have been disqualified does not need to cast a deciding vote in the case to violate the Due Process Clause.[3]

References

External links

- Text of Aetna Life Insurance Co. v. Lavoie, 475 U.S. 813 (1986) is available from: Cornell Findlaw Google Scholar Justia

This article incorporates written opinion of a United States federal court. As a work of the U.S. federal government, the text is in the public domain.