Abba Bagibo

| Ibssa Abba Bagibo | |

|---|---|

| King of Limmu-Ennarea | |

| Reign | 1825-1861 |

| Predecessor | Bofo Abba Gomol |

| Successor | Abba Bulgu |

| Born | 1802 |

| Died | 1861 |

| Spouse | Genne Minjoti |

| Issue | Abba Bulgu |

| Dynasty | Kings of Limmu-Ennarea |

| Father | Bofo Abba Gomol |

| Religion | Islam, Waaqeffanna |

Abba Bagibo (1802–1861), born Ibssa (meaning 'the light'), was the second ruler of the Kingdom of Limmu-Ennarea, the most influential and prosperous of the Oromo Gibe states during the first half of the 19th century. His reign marked the apogee of the Kingdom’s political and economic ascendancy.

Family

Ibssa Abba Bagibo was the son of Bofo Abba Gomol, a renowned Abba Dula (a Gadaa official responsible for military leadership) and the founder of the Kingdom of Limmu Ennerea. Although Bofo was the son of a hereditary Abba Bokku ( Father of the Law), he was initially but a poor nobleman, widely recognized for his exceptional bravery.[1] He cultivated his land along the frontier with Nonno, a neighboring territory that frequently encroached upon Limmu’s domain. From time to time, Bofo launched retaliatory raids into Nonno, invariably returning with plunder. His exploits brought him considerable fame, and Abba Rebu, one of the most prominent Soressa (chiefs) of Ennerea, offered him his daughter in marriage. From this union was born Abba Bagibo.[2][3]

According to the historian Mordechai Abir, a local tradition maintains that this marriage was a strategic political alliance between two rival clans: the Sapera, from which Abba Gomol descended, and the Sigaro, to which Abba Rebu belonged.[4]

Abba Bagibo harbored the ambition of unifying the Gibe region through dynastic alliances. As a result, he contracted multiple marriages with royal families from neighboring Gibe states. In 1823, his marriage to Genne Minjoti, daughter of the King of Kaffa, was solemnized. She remained his principal wife, until her death.[5] Later, in 1843, he successfully negotiated a marriage with the King of Kaffa’s sister. Similarly, in 1846, he sought the hand of the daughter of the King of Kullo. Over the course of his reign, Abba Bagibo took approximately thirteen queens—some of whom, such as the famed Kuletti, were celebrated throughout the kingdom for their extraordinary beauty—as well as more than three hundred concubines, who bore him twenty-seven sons and forty-five daughters.[6][7][8] One his sons, Abba Bulgu, succeeded him as king of Limmu Ennerea upon his death in 1861.[9]

Early Life and Education

Abba Bagibo was born in 1802 and raised in Sappa, the first capital of the Kingdom of Limmu-Ennarea. His father, Abba Gomol, embraced Islam shortly after ascending to power, influenced by Muslim traders who had settled in the region. As a result, Abba Bagibo received a rudimentary Islamic education. According to historian Mohammed Hassen, Muslim religious teachers appear to have exerted a formative influence on his mind from an early age.[10]

Originally named Ibssa, the young prince is said to have inherited much of his father’s vigor, though not his courage. He spent his formative years immersed in military training within his father’s army, acquiring both the practical skills of warfare and the ideological grounding necessary for leadership. It was during this period that he gained the name by which he would later be known—Bagibo—a nickname derived from his favorite horse.[11]

Rise to Power

In 1825, at the age of twenty-three, Abba Bagibo staged a coup d’état, compelling his father, Bofo Abba Gomol, to abdicate. Backed by a strong base of political and military support, he dictated the terms of his father's resignation.[12] Though stunned by his son’s rebellion, Bofo was not inclined to relinquish power without resistance, particularly as he was already confronting a rebellion around Saqqa. Following his successful seizure of power, Abba Bagibo allowed his father to remain in his massera (royal residence) in the former capital, Sappa.[13]

Reign (1825–1861)

Foundation of the New Capital at Saqqa

Abba Bagibo’s first challenge as ruler was the suppression of the Saqqa rebellion. According to Mohammed Hassen, both literary sources and oral tradition agree that he advanced with strategic caution—first consolidating his authority and ensuring the preparedness of his army. During this period, he also gained valuable political ground by securing the support of his grandfather, Abba Rebu, a powerful figure in Saqqa. This alliance not only facilitated the defeat of the rebellion but also helped divide the opposition. His swift and decisive victory opened the way for sustained military campaigns against neighboring groups such as the Nonno and Agallo, enabling significant territorial expansion.[14]

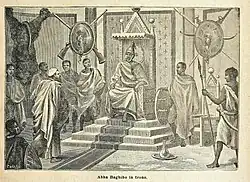

Having pacified the region, Abba Bagibo founded a new capital at Saqqa, establishing it as both the political heart of Limmu-Ennarea and the commercial hub of the Gibe region. Its strategic location at the convergence of major caravan routes transformed Saqqa into a thriving marketplace, where merchants of diverse origins converged for trade. The king’s revenues appear to have steadily accumulated in the royal treasuries and storehouses, deriving primarily from three sources: taxation on land and its agricultural output, income generated from the royal domains, and profits from trade. While precise figures for each category remain unknown, it is reasonable to infer that trade, in particular, constituted a significant portion of royal income—especially given Saqqa’s strategic position as a major commercial hub in the Gibe region. The French explorer Arnaud d’Abbadie, who visited the region in the mid-19th century, famously likened the royal court at Saqqa to that of King Solomon:

For the first time, I finally beheld what, in my childhood, I had imagined to be the court of Solomon. In these outer galleries supported by wooden columns stood a fairly large assembly, arranged in an angle against the wall—composed mostly of elderly, corpulent men wearing small, sharply pointed conical hats made of dried goat skin. No brims—just the cone in all its purity. At the rear of the semicircle formed by the courtiers, and leaning against the house wall, stood a small earthen throne, about a meter high, flanked on either side by two steps. It supported a hollow, backless seat with three legs, carved from a single piece of wood—topped by His Supreme Majesty.[15]

He further remarked on Abba Bagibo’s residence in the capital:

His house in Saqqa is enclosed within several compounds, better built than anything of the kind I have seen, even in Europe.[16]

As part of his plan to gain favor and solidify his rule, Abba Bagibo called artists and workers from Gibe to build fifteen royal residences that turned into busy trade spots in all parts of his land. The most famous among them was at Garuqqe near Saqqa. Known for its gate built in a style resembling Chinese architecture, the Garuqqe house was not just the most lively work spot of the Kingdom where known goods from Limmu-Ennarea were made and sent out everywhere but also a center of power and community life. [17]

Religion

As a Muslim ruler, Abba Bagibo positioned himself as a patron and defender of Islam, and the growing Muslim population of Saqqa contributed to the spiritual prestige of the capital. At the same time, he remained attached to traditional Oromo religious practices. He continued to participate in key ritual ceremonies and maintained relations with the Abba Muudaa, the highest religious authority in Oromo spirituality, to whom he regularly sent gifts. In the 1840s, the French explorer Antoine d’Abbadie documented one such religious ceremony under the title, “The Oromo Sacrifice.”:

The great priest was Abba Bagibo, in person and the God was good old mount Agamsa. The king himself walked towards the sacrificial animal pronouncing loudly; 'Oh God [Qallo Agamsa] where the goats are fed, I give you a bull, so that you favour us, protect our country, guide our soldiers, prosper our country side, and multiply our cows: I give you a bull, I give you a bull.' This done the animal was knocked down and the king cut its throat with a sabre, without stooping to do so. A small piece of meat was cut from above the eye and it was thrown into the fire together with myrrh and incense. Then all the courtiers returned to the palace. Someone told me that the slaves of the king would eat the flesh of the sacrificed animal.[18]

Abba Bagibo demonstrated notable religious tolerance, both in his personal beliefs and in his governance. Although a Muslim by faith, he allowed the establishment of Catholic missions within his Kingdom and showed respect for the diverse religious practices of his subjects. The King admired and respected Cardinal Massaja, the first Catholic bishop of Oromoland, and he treated him with the greatest courtesy. Massaja was impressed by the kindness which he received from Abba Bagibo. The king’s considerable charm, hospitality, kindness, and support for the Catholic mission can be seen again and again in Massaja’s writings.[19]

Policy Toward Neighboring States

Abba Bagibo continued the wars initiated by his father with greater vigor and success. In the early years of his reign, his campaigns focused primarily on the Kingdom of Gumma, which he managed to defeat repeatedly, though without ever managing to reduce it to tributary status. Realizing the futility of these efforts, he abandoned that objective and compensated for these losses by subjugating Jimma Badi, a disorganized group that became a tributary of Limmu-Ennarea. This success secured the trade route to the kingdom of Kaffa.[20]

He later attempted a peaceful approach toward Gumma, but this failed with the rise of the state of Jimma Abba Jifar in 1830, which annexed Jimma Badi and cut Limmu-Ennarea off from its border with Kaffa. Gumma and Jimma formed an alliance against their common enemy, forcing Abba Bagibo to abandon his ambitions on the western and southern fronts.

He then turned to the east and north, expanding his control over territories such as Agallo, Botor, Badi Folia, Nonno, and even Janjero (Yamma). His influence reached the famous market of Soddo, in what is now the Shewa region, during the reign of King Sahle Sellassie. Abba Bagibo also aimed to extend his Kingdom toward the Abbay and western Wallaga, though these efforts failed. His focus on the northern and eastern fronts brought significant military victories and economic benefits. Trade routes through Soddo and Agabja, connecting Gojjam and the Muslim land of Wollo, came under his control, increasing the kingdom’s wealth.

By 1840, at the height of his power and reputation, Abba Bagibo considered conquering the wealthy yet unstable land of Torban Gudru. Although tempted, he exercised caution, aware of the Gudru’s 15,000 cavalry and the simultaneous attacks from Gumma and Jimma. Concerned with preserving his gains and the growing power of Jimma Abba Jifar, he chose a strategy of alliance.

He thus proposed a coalition with Goshu, governor of Damot and Gojjam, who also sought a share of Gudru’s wealth. This initiative originated with Bagibo and is confirmed by a letter he sent to Goshu in 1840. Originally written in Oromo and translated into Arabic, the letter was passed on to Arnauld d’Abbadie, who produced a flawed French version. Despite its archaic language and imperfections, the letter sheds light on Abba Bagibo’s evolving policy: using wealth to strengthen his power and kingdom — a clear shift in strategy during the latter part of his reign.[21]

Death and Succession

Abba Bagibo died on September 24, 1861, at the age of fifty-nine, after a reign of thirty-six years. Upon falling suddenly ill, and sensing the imminence of death, he summoned all his sons and the three members of the Council of State. In a symbolic gesture intended to ensure a smooth succession and avert internal conflict, he handed his gold ring to Abba Bulgu, declaring him his heir.[22]

Despite this orderly transition, Abba Bagibo’s death marked the end of Limmu Ennarea’s golden age. His successor, Abba Bulgu, proved unequal to the task of preserving his father’s legacy. As historian Mordechai Abir notes, Abba Bulgu was an “untalented and fanatical Muslim son,” whose misrule accelerated the kingdom’s decline.[23]

References

- ^ d'Abbadie, Arnaud (1983). Douze ans de séjour dans la Haute-Éthiopie vol. III. CITTA DEL VATICANO Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana. p. 258.

- ^ Mordechai, Abir (1965). "The Emergence and Consolidation of the Monarchies of Enarea and Jimma in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century". The Journal of African History. 6 (2). Cambridge University Press: 209. JSTOR 180198.

- ^ Hassen, Mohammed (1994). The Oromo of Ethiopia: A history 1570-1860. (Trenton: Red Sea Press. p. 103.

- ^ Mordechai, Abir (1965). "The Emergence and Consolidation of the Monarchies of Enarea and Jimma in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century". The Journal of African History. 6 (2). Cambridge University Press: 209. JSTOR 180198.

- ^ Hassen, Mohammed (1994). The Oromo of Ethiopia: A history 1570-1860. (Trenton: Red Sea Press. p. 163.

- ^ Hassen, Mohammed (1994). The Oromo of Ethiopia: A history 1570-1860. (Trenton: Red Sea Press. p. 187.

- ^ d'Abbadie, Arnaud (1983). Douze ans de séjour dans la Haute-Éthiopie vol. III. CITTA DEL VATICANO Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana. p. 263.

- ^ Pankhurst, Richard (1984). Reviewed Work: Douze ans de séjour dans la haute éthiopie (abyssinie). Tome troisième by Arnauld d'Abbadie. The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, No. 2. p. 270-271. JSTOR 25211717.

- ^ Mordechai, Abir (1968). The era of the princes: the challenge of Islam and the re-unification of the Christian empire, 1769-1855.. Longmans. p. 93.

- ^ Hassen, Mohammed (1994). The Oromo of Ethiopia: A history 1570-1860. (Trenton: Red Sea Press. p. 105.

- ^ Hassen, Mohammed (1994). The Oromo of Ethiopia: A history 1570-1860. (Trenton: Red Sea Press. p. 106.

- ^ d'Abbadie, Arnaud (1983). Douze ans de séjour dans la Haute-Éthiopie vol. III. CITTA DEL VATICANO Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana. p. 260.

- ^ Hassen, Mohammed (1994). The Oromo of Ethiopia: A history 1570-1860. (Trenton: Red Sea Press. p. 164-165.

- ^ Hassen, Mohammed (1994). The Oromo of Ethiopia: A history 1570-1860. (Trenton: Red Sea Press. p. 166.

- ^ d'Abbadie, Arnaud (1983). Douze ans de séjour dans la Haute-Éthiopie vol. III. CITTA DEL VATICANO Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana. p. 254.

- ^ d'Abbadie, Arnaud (1983). Douze ans de séjour dans la Haute-Éthiopie vol. III. CITTA DEL VATICANO Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana. p. 255.

- ^ Hassen, Mohammed (2011). Abba, Bagibo I. Dictionary of African Biography. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-538207-5.

- ^ Hassen, Mohammed (1994). The Oromo of Ethiopia: A history 1570-1860. (Trenton: Red Sea Press. p. 171.

- ^ Hassen, Mohammed (1994). The Oromo of Ethiopia: A history 1570-1860. (Trenton: Red Sea Press. p. 172.

- ^ Hassen, Mohammed (1994). The Oromo of Ethiopia: A history 1570-1860. (Trenton: Red Sea Press. p. 175.

- ^ Hassen, Mohammed (1994). The Oromo of Ethiopia: A history 1570-1860. (Trenton: Red Sea Press. p. 175-178.

- ^ Hassen, Mohammed (1994). The Oromo of Ethiopia: A history 1570-1860. (Trenton: Red Sea Press. p. 195.

- ^ Mordechai, Abir (1968). The era of the princes: the challenge of Islam and the re-unification of the Christian empire, 1769-1855.. Longmans. p. 93.