98th Illinois Infantry Regiment

| 98th Regiment Illinois Volunteer Infantry/Illinois Volunteer Mounted Infantry | |

|---|---|

Illinois flag | |

| Active | 1862–1865 |

| Disbanded | July 29, 1865 |

| Country | United States |

| Allegiance | Union |

| Branch |

|

| Equipment | Spencer repeating rifle |

| Engagements | |

| Insignia | |

| 1st Division, XIV Corps |  |

| 4th Division, XIV Corps |  |

| Illinois U.S. Volunteer Infantry Regiments 1861-1865 | ||||

|

The 98th Regiment Illinois Volunteer Infantry, later the 98th Regiment Illinois Volunteer Mounted Infantry, was an infantry and mounted infantry regiment that served in the Union Army during the American Civil War.[1]

Service

After the first year of war and the debacle on the Peninsula caused the Lincoln administration to realize that the war would take longer than first expected and many more men, on July 1, 1862, Lincoln issued a call for 300,000 volunteers for three-year commitments. Illinois’ quota under this call was 26,148. [2] The 98th Illinois Volunteer Infantry was raised in response to this quota. Col. John J. Funkhouser, of Effingham, IL,[3][note 1] organized and trained it at Centralia, IL,[note 2] in southern Illinois, during the summer of 1862. He mustered it into federal service on Wednesday, September 3.[5] By this time of the war, Illinois had imported stocks of rifle-muskets from Europe to make up for the shortfalls in the standard Springfields, and the state issued Austrian Rifle Muskets to the 98th Illinois.[6]

Initial Deployment

In the Western campaigns earlier in 1862, U.S. forces had largely driven organized Confederate forces from Kentucky and large parts of Tennessee.[7] The Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers were now U.S. Navy avenues for logistics and troop movements. The Tennessee state capital, Nashville, the railroad hub at Corinth, and New Orleans, the Confederacy's largest city at that time, were back in federal hands. Vicksburg, on the Mississippi, was now a target for the Union commands, ergo, Confederate Gen. Braxton Bragg decided to divert U.S. attention by invading Kentucky, the most southern of the southern border states,[7] which would occur simultaneously Gen. Lee's invasion of Maryland and Maj. Gen.s Earl Van Dorn's[8] and Sterling Price's attack to regain the rail center at Corinth. Kentucky produced cotton (in west Kentucky) and tobacco on large scale plantations similar to Virginia and North Carolina in the central and western portions of the state with slave labor, and was the primary supplier of hemp for rope used in the cotton industry. The state was also a major slave trade center especially out of Louisville.[7]

Bragg had begun his campaign in August, hoping that he could rally secessionist supporters in Kentucky (similar to Lee in Maryland at the same time) and draw Union forces under Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell back to protect the Ohio River.[9] Bragg sent his infantry by rail from Tupelo, MS, to Chattanooga, TN, while his cavalry and artillery moved by road. By moving his army to Chattanooga, he was able to challenge Buell's advance on the city.[10][11]

On Monday, September 8, Funkhouser received orders to take the 98th Illinois via the Ohio and Mississippi Rail Road to Louisville, KY. At Bridgeport, IL, their train derailed killing eight men and injuring seventy-five.[12] Arriving in Jeffersonville, IN, opposite Louisville the next day, they marched into Camp Jo Holt. Once his forces had assembled in Chattanooga, Bragg then planned to move north into Kentucky in cooperation with Lt. Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith, who was commanding a separate force operating out of Knoxville, Tennessee. In response to Bragg's advances, the 98th remained north of the Ohio River for ten days as part of the defense of Louisville.[12]

Meanwhile, Bragg, advancing to Glasgow, KY, pursued by Buell, Bragg approached Munfordville, a station on the Louisville & Nashville Railroad (L&IRR), about 70 miles (110 km) south of Louisville, and the location of an 1,800 foot long railroad bridge crossing Green River, in mid-September.[7] The 98th Illinois' future commander Col. John T. Wilder,[note 3] commanded the Union garrison at Munfordville, which consisted of three new, raw regiments behind extensive fortifications. After rebuffing the Rebels on September 14 and unaware that Buell was nearing him, Wilder surrendered to Bragg's army on Tuesday, September 16 and became prisoners of war (POWs) for two months.[14]

In response, on Sunday, September 19, the regiment marched 18 miles (29 km) south of Louisville to a blocking position at Shepherdsville. Eleven days later, September 30, they were ordered 90 miles (140 km), via Elizabethtown, to Frankfort to protect the capital. While the 98th Illinois was on the march, Bragg had participated in the inauguration of Richard Hawes as the provisional Confederate governor of Kentucky on Saturday, October 4.[7] The next Wednesday, October 8, the wing of Bragg's army under Maj. Gen. Leonidas Polk met Buell's army at Perryville (60 miles (97 km) southeast of Louisville amd 40 miles (64 km) southwest of Lexington) on October 8 and won a tactical victory against him. Despite this result, Bragg ordered his army to retreat through the Cumberland Gap to Knoxville, labeling it a withdrawal and the successful culmination of a giant raid. He had reasons for withdrawing in that news had arrived that Van Dorn and Price had failed at the Second Battle of Corinth, just as Lee had failed at Antietam.[7]

This all occurred while the 98th Illinois were on their 90 miles (140 km) march to Frankfort, where they arrived on Thursday, October 9. Two days later, the regiment, moved 13 miles (21 km) to Versailles taking 200 sick POWs from the Rebel army hospital that they had abandoned.[12] On Monday, the regiment returned to the capital. At this time, the regiment was brigaded in the Col. Abram O. Miller's 40th Brigade, with the 72nd and 75th Indiana, 123rd Illinois, and 13th Indiana Battery in Brig. Gen. Ebenezer Dumont's 12th Division in the Army of the Ohio.[12][15]

The War Department was disappointed with Buell who although the strategic victor, had lost the battlefield to Bragg at Perryville.[11] As a result of his part in rebuffing the Confederate advamce on Corinth, William S. Rosecrans was given command of XIV Corps (which, because he was also given command of the Department of the Cumberland, would soon be renamed the Army of the Cumberland), on October 24. Rosecrans was promoted to the rank of major general (of volunteers, as opposed to his brigadier rank in the regular army), which was applied retroactively to March 21, 1862, so that he would outrank fellow Maj. Gen. Thomas who had earlier been offered Buell's command, but turned it down out of loyalty to Buell.[16][note 4] Rosecrans soon became popular with his men as "Old Rosy and began organizing his army.[18]

Two days after Rosecrans took command, Sunday, October 26, the 450th Brigade marched out of Frankfort for Bowling Green. Their route took them southwest via Bardstown, Mumfordsville, and Glasgow, to Bowling Green.[12] The brigade, averaging 15 miles (24 km) per day, completed the roughly 130 miles (210 km) on Monday, November 3.[12] A week later, November 10, the 98th Illinois' brigade moved with its division to Scottsville.[12] Roughly two weeks later, Tuesday, November 25, the division moved into Tennessee to Gallatin, and on Friday, November 28, to Castalian Springs. Two weeks and two days later, Sunday, December 14, the regiment moved to Bledsoe Creek.[12] On 22 December 1862 in Gallatin, Col. Wilder, who with his regiment had ended parole mid-November, took command of the 40th Brigade which at that time consisted of the 98th and 123rd Illinois Infantry Regiments, the 17th, 72nd, and 75th Indiana Infantry Regiments, and the 18th Indiana Battery of Light Artillery.[19] Maj. Gen. Reynolds took command of the 12th Division on Tuesday, December 23.[12]

The 98th Illinois was now with its most famous brigade commander. Wilder's initial combat mission was to pursue another of Morgan's raids into Kentucky intended to sever the Army of the Cumberland's primary supply line. Lacking sufficient cavalry to screen his army as he moved south toward what would be the Battle of Stones River as part of the Stones River Campaign, Rosecrans again had to use infantry to chase off Morgan. He tasked Rewynolds to use his infantry brigades for this mission. Trying to speed their movement, these infantry units deployed partially by rail. Wilder also unsuccessfully tried to replicate the use of mule-drawn wagons with the addition of men mounting the mules pulling the wagons.[20] Unfortunately, they still traveled the majority of the pursuit on foot over unpaved roads. Despite the use of rail and wagons to speed up the pursuit, the mission was a failure with Morgan's command escaping at the Rolling Fork River.[21] The difference in speed between cavalry and infantry made the pursuit near impossible. On Boxing Day, December 26, Wilder's brigade had marched northward after Morgan, arriving Wednesday, New Year's Eve, December 31, at Glasgow.[12]

Mounted infantry

On Friday, January 2, 1863, the 989th and its brigade marched to Cave City,[22] and, on Sunday, the regiment's division took the Louisville and Nashville Railroad (L7NRR) 78 miles (126 km) to Nashville. After detraining, the division with the 98th Illinois, marched the 30 miles (48 km) to join the Army of the Cumberland (AoC) in camp by the Stones River battlefield by Murfreesboro which they reached at dusk on Tuesday, January 6. The army was recovering from the battle there and resupplying and drilling. Rosecrans reorganized the army further and 12th Division became the 5th Division of Maj. Gen. Thomas' Center Corps and the 40th Brigade became the 2nd Brigade in that division and once again commanded by Col. Miller.[22] Eight days later, a further reorganization renumbered it as the 1st Division and added the 123rd Illinois to the brigade, again commanded by Wilder.[12] On Saturday, January 24, moved through Bradyville, and, on 25th, returned.

Despite the AoC's victory at Murfreesboro, the war in its area of operations (AOR) was still hanging in the balance. It was still struggling with Bragg's Confederate Army of Tennessee to control Tennessee and all its valuable resources and strategic rail interchanges. Strategically important, Tennessee had Union loyalists in its east that Lincoln wanted to liberate and bring back under Federal protection. It also was a critical rail link between Virginia and the west of the Confederacy that supplied Rebel forces in Tennessee and throughout the Eastern Theater. The state also produced food and mineral supplies for the war effort.[23]

After Stones River, while he rested and reorganized his AoC, Rosecrans, pushed back against the War Department's pressure to begin a spring offensive against the Rebels. One of his reasons was a deficiency in cavalry as the Rebels had twice as much.[23] Moving further south and east in Tennessee would further lengthen his already lengthy supply lines, which were already being raided by Confederate cavalry. With good reason therefore, he pestered Washington for more cavalry yet the War Department mistakenly saw his requests as an excuse to not move.[24] The failure to capture Morgan and other mounted Confederate raiders had shown Rosecrans had legitimate reasons to ask for more cavalry. After Washington's denial of more cavalry, Rosecrans and his subordinates, with Wilder very involved in the discussion, tried to find a solution. The experiment with wagons from the October events was revisited and analyzed, and it became apparent that the solution to their problems was the early role of dragoons as mounted infantrymen.[25] Rosecrans thought an infantry brigade mounted on horseback and armed with more firepower than an ordinary brigade might be a solution. This was how the 98th Illinois and Wilder's brigade acquired horses and repeating rifles.[26]

Several times, Rosecrans wrote to the Union General-in-Chief Maj. Gen. Halleck stating his desire to convert or establish units of mounted infantry and asking for authorization to purchase or issue enough tack to outfit 5,000 mounted infantry.[27] He also believed, with Wilder in agreement, that he needed to outfit all of his cavalry with repeating weapons. When he felt he was not being heard, he went over Halleck directly to War Secretary Edward M Stanton.[28]

In Wilder, an innovative and creative man, Rosecrans found an eager acolyte for mounted infantry as a solution. On Monday, February 16, Rosecrans authorized Wilder to mount his brigade.[29] The regiments also voted on whether to convert to mounted infantry. Col. Funkhouser and his men voted for the transition possibly motivated by the frustration of never catching the Rebel raiders when they attacked.[26] The 17th amd 72nd Indiana also wanted to transition, but the 75th Indiana voted against the change. The 123rd Illinois who had wanted to become mounted infantry transferred from the 1st Brigade of the 5th Division of XIV Corps to replace them.[30] In addition, the briagde's artillery battery, the 18th Independent Battery Indiana Light Artillery under the future pharmaceutical giant and benefactor of Purdue, CAPT Eli Lily,[31] had ten artillery pieces, six 3-inch Ordnance Rifle pulled by eight horses each and four mountain howitzers pulleed by two mules each. This gave the brigade increased artillery firepower.[32]

Finding mounts

Throughout February and March 1863, Wilder started a lengthy process of sweeping the Tennessee countryside to round up enough mounts for his entire brigade[33] Instead of getting mounts sent on from federal remount agencies, the 98th Illionois and its brigade mates obtained them from the countryside. Fairly early in the process, the obstinacy of the mules led to horses becoming the priority. Moving out from Murfreesboro, the 98th Illinois' patrols combed the local civilian population and confiscated horses and mules for their purposes. Early efforts yielded horses not meeting army standards, but needing them for transport and not charges, the men were not picky taking what they found. The government's policy of quartermasters giving receipts was ignored as horses and mules were frequently seized as contraband.[34] Wilder boasted that it did “not cost the Government one dollar to mount my men.”[35] The 18th Illinois regiment was ordered to mount its men on Sunday, March 8.[36] By the following Saturday, March 14, the regiment had 350 men mounted. Shortly afterward the whole Brigade was mounted.[37]

In theory and in practice, the 98th Illinois would ride their horses to travel rapidly to contact, but upon engagement, fight dismounted. The horses and mules required saddles, tack, feed bags, grooming equipment, and farrier support, which the men either purchased locally or took from captured or confiscated stocks. The increase in the size of the brigade's supply train led to a further increase in the number of wagons, mule,s and horses to support the brigade.[38] The 98th Illinois and its brigade mates began training with their horses. Wilder, Funkhouser, the other regimental commanders, and their staffs next focused on developing new tactics.[35] They adapted concepts from the cavalry and the infantry in their tactics and standard procedures. They developed a transition movement from horseback to forming infantry line of battle. To facilitate this they took the standard cavalry one horse holder for to three men in the battle line from the cavalry.[39] This training ran concurrently with the constant forage expeditions and search for better mounts and tack from the countryside. The 98th was lucky in having been mounted most of the month and by the end of March, most of the brigade was mounted, and Wilder, Funkhouser et al. could begin plan for the primary purpose of countering Confederate regular and irregular raids on the AoC's supply lines.[40] Their resulting speed of deployment, earned the brigade the nickname, "The Lightning Brigade." The regiment and its mates would prove the validity of its conversion in the campaign in the Western theater. [note 5]

Finding a suitable weapon

As well as mounting the command for faster deployment, Wilder felt that muzzle-loaded rifles were too difficult to use when traveling on horseback. Like Rosecrans, he also believed that the superiority of repeating rifles was worth their price in return for the great increase in firepower. The repeating rifles also had the standoff range like the standard infantry Lorenzes, Springfields, and Enfields in use by the Army of the Cumberland. Wilder felt the repeating and breech loading carbines in use by the Federal cavalry lacked the accuracy at long range that his brigade would need.[41]

While Rosecrans looked at the five-shot Colt revolving rifle that would equip other units in the Army of the Cumberland (particularly seeing action with the 21st Ohio Volunteer Infantry Union forces at Snodgrass Hill during the Battle of Chickamauga), Wilder was initially opting for the Henry repeating rifle as the proper weapon to arm his brigade. In early March, Wilder arranged a proposal for New Haven Arms Company (which later became famous as Winchester Repeating Arms) to supply his brigade with the sixteen-shot Henry if the soldiers paid for the weapons out of pocket. He had received backing from banks in Indiana on loans to be signed by each soldier and cosigned by Wilder, but New Haven could make a deal with Wilder despite the financing.[42][43]

Into this void stepped by Christopher Spencer. After attending a promotional demonstration for the Army of the Cumberland of his Model 1860 Spencer Army rifle, Wilder proposed the Henry arrangement to Spencer. Spencer agreed and got the Ordnance Department to send a shipment to the Army of the Cumberland.[44] The shipment armed all men of the brigade, as well as several other units in the AoC.

The regiment's new weapon used a tubular magazine in the butt stock, fitted with a coil spring and holding seven Spencer No. 56 .52-Caliber copper rimfire cartridges that fed into the breech allowing the user to fire as quickly as they could work the lever action.[45] This rifle's increase in firepower would quickly make it one of the most effective weapons in the Civil War. With new mounts and new weapons, the brigade worked out new tactics. Alongside the Army of the Cumberland's other mounted infantry units, Wilder developed new training and tactics through March and June 1863.[46] While awaiting the Spencers, Wilder sent the regiments out as part of their training. On Wednesday, April 1, the 98th Illinois moved out on an eight days' scout, going to Rome, Lebanon and Snow's Hill before returning to Murfreesboro the Tursday of the next week.[47] After a three-day stay in camp, on Monday, April 13, the regiment moved with the brigade moved to Lavergne and Franklin, and returned the next day. The following Monday, April 20, the brigade, with the 98th Illinois, moved to McMinnville where it destroyed a cotton factory and captured a railroad train. On Wednesday anmd Thursday, the regiment and its brigade, moved via Liberty to Alexandria where it joined its parent command, Reynold's 4th Division on April 23. Monday, April 27, saw the brigade move to Lebanon where it captured a large number of horses and mules and by Wednesday, April 29th, it returned to Murfreesboro.[47]

Developing training and tactics

During the months of April and May, the regiment made three weekly brigade sorties from the brigade's Murfreesboro base. The patrols were combined raids on Confederate cavalry operating nearby, the destruction of Confederate supplies, and further foraging for horses, food, and material (mainly saddles and tack). [48] On Wednesday, April 1, the 98th Illinois moved out with the brigade on an eight days' scout, going to Rome, Lebanon and Snow's Hill,[note 6] and returned the following Thursday, April 9.[12] The next week, on Monday, April 13, the brigade rode to Lavergne and Franklin, and returned the next day, Tuesday without enemy contact made by the regiment nor any command in the brigade.[50] The following Monday, April 20, the 98th Illinois was on the road with the brigade.[12] Rosecrans had ordered a larger operation to McMinnville to destroy the enemy cavalry and destroy their stores of resources used to conduct their raids. Rosecrans told both Brig. Stanley, his cavalry corps commander, and Reynolds, the 18th Illinois' 5th Division commander that they had command of Wilder's 2nd Brigade.[51] The 98th Illinois and other brigade units worked closely with Col Long’s Cavalry brigade, while the unmounted 75th Indiana operated with Reynolds' other regular infantry. On Tuesday, U.S. units entered McMinnville, occupied by pickets of Morgan's Brigade with both sides claiming the other left the field.[52] Rosecrans clearly stated that he wanted the force to engage and destroy the Rebel cavalry, but this was not accomplished.[53] Reynolds and Wilder were successful in sacking the town and its stores of supplies. Wilder destroyed or captured the train depot, 600 blankets, several thousand pounds of bacon, 200 bales of cotton, a cotton factory, two mills, the courthouse, some private homes. He also captured 200 prisoners, and a railroad train.[54] All three sorties generally failed to decisively engage or deter Confederate cavalry forces, aside from temporarily driving them from the various towns.[40] On the second and third tasks, the brigade performed very well.

Of the three missions given to the brigade on the three sorties, pursuit and destruction of the enemy was the most difficult and dangerous especially with three of the regiments still untested in combat while the other two, destroying/confiscating supplies/resources and rounding up horses and tack were easier in comparison.[55] Whatever the reason, Wilder focused on the latter two and complied with that portion of Rosecrans’ orders. In addition to the destruction in McMinnville noted above, Wilder went back to Murfreesboro with 678 horses and mules.[56] The contradicting commands to Long and Reynolds may have played a role in the failure to destroy the enemy in McMinnville.[57] A soldier in Reynolds' infantry wrote that they did not pursue the Confederates was that “...the officer in command of the advance would not allow the men to go ahead of him in pursuit...” and Reynolds admitted in his after-action report that he did not allow a pursuit due to the exhaustion of his men and horses.[58][59]

After nine days, the division returned to Murfreesboro entering and dismounting on Wednesday, April 29. A week later, May 6, the 75th Indiana exchanged places in the 1st Brigade of the 4th Division with the 123rd Illinois who immediately began the mounting process.[60] Combat veterans like the 17th Indiana had seen combat, the 123rd Illinois had fought at the Battle of Perryville, where 36 men were killed in action and 180 wounded.[61] The men of the untested 72nd Indiana and 98th Illinois still had yet to prove themselves on the battlefield and trained hard to be ready when called upon.[62] Throughout the month, the 98th and the other regiments went out on foraging expeditions to find horses and equipment for the 123rd Illinois as well as upgrading their own horses and gear. By mid-May, the AoC's shipment of Spencers arrived, and the brigade was fully engaged in learning to maintain and shoot the new rifles.[60] On May 23, Funkhouser took the 98th Illinois on a reconnaissance to the McMinnville and Manchester Railroad (M&MRR) front, making contact with the enemy's pickets, killing two and wounding four.[60] At the end of the month, Sunday, May 31, the 98th Illinois officially exchanged their Austrian Lorenz rifle-muskets for their new Spencers.[63]

Armed with their new rifles, the 98th joined a brigade-level scouting/raid mission in June back to Liberty on Monday, June 4. There they attacked two regiments of Brig. Gen. Wharton’s cavalry, the 1st Kentucky and 11th Texas.[64] Lasting Monday evening into Tuesday, June 5, the 98th Illinois and its brigade drove them out of town and captured 20 prisoners and five wagons.

By mid-June, the brigade had had a chance to try out its new capabilities against the enemy. By then, all the Spencers had been issued, and the men had familiarized themselves with it. The 98th Illinois soldiers and their brigade mates soon realized the great advantages the breech-loading repeating rifle held over the muzzleloader, and they exuded confidence in themselves, their leaders, their new tactics, and their treasured new weapons.[65] The bulk of the logistical effort to mount everyone was complete, although throughout the summer the 98th Illinois like the other mounted infantry would continually seek to find better horses than the one they were riding.

As Rosecrans now began setting up for his awaited spring offensive, his AoC now had a lethal, mobile strike force to stop Confederate raiders, however, Rosecrans instead used the 98th Illinois and its brigade mates in the cavalry mission as raiders. From Wilder's own reports, he deemed this mission to be his primary goal while glossing over his opportunities to deal a serious blow to any Confederate cavalry force,[66] a fundamental shift from the mounted infantry's initial primary purpose, protecting supply lines by stopping Confederate cavalry raids.[65]

On Wednesday, June 10, the 98th Illinois attacked the enemy at Liberty, driving their rear guard of 150 men to Snow's Hill. In preparation for his upcoming campaign, Rosecrans sent Wilder's brigade, Tuesday, June 16, to Dark Bend.[67]

By the middle of June, the 98th Illinois had completely transformed from infantry afoot to mounted infantry.[65]The regiment was highly mobile and working well as mounted infantry. Every man was mounted and had all equine paraphernalia necessary.[67] The regiment's members had gradually learned the complicated drill necessary for horse units, how to pack for long expeditions, and how to care for their animals. The same applied to the brigade as a whole. A down side to the transition to horseback, however, increased the required quantity need for food, new horses, and supplies to operate.[68] Constant foraging for feed and the soldiers continual effort to better their equipment and mounts left a trail everywhere the brigade went. The 98th Illinois and the rest of the brigade had changed greatly from how they were when Wilder took command the prior December 1862.[69]

The 2nd Brigade's new mobility gave Rosecrans and his subordinates a capability to send the brigade to a crucial point on a battlefield much more rapidly than regular infantry.[69] Rosecrans could react to a developing battle situation more quickly with mounted infantry. The 98th Illinois’ and its colleagues’ Spencers were only slightly out-ranged by the regular infantry's rifle-muskets contrary to the equally highly mobile cavalry whose carbines were outranged by infantry armed with modern rifle-muskets.[69] The 98th Illinois and the rest of Wilder's brigade's increase in firepower was deemed to more than compensate for the slightly shorter range. The new, improved capabilities of the still untested 98th Illinois and 72nd Indiana plus the combat proven 123rd Illinois and 17th Indiana would soon be tested.[70]

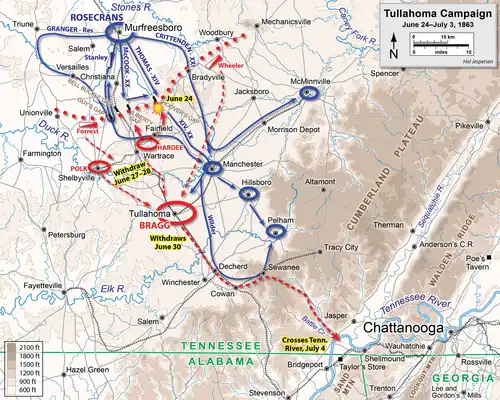

The Tullahoma campaign

On June 2, Halleck telegraphed Rosecrans threatening to send some of his troops to support Grant if he did not move on Bragg. After polling his subordinates,[71] he pushed back. On Tuesday, June 16, Halleck gave an ultimatum demanding an immediate movement forward. When Rosecrans responded that the AoC would be moving within five days, Halleck relented.

On Tuesday, June 23, Rosecrans deployed forces to feign an attack on Shelbyville while massing forces against Bragg's right.[72] His troops moved out toward Liberty, Bellbuckle, and Hoover's Gaps through the Highland Rim (near Beechgrove, Tennessee).[73] Early on Wednesday morning, Rosecrans reported that the Army of the Cumberland had begun to move against Bragg.[74] That morning at 3:00 a.m., in pouring rain that would persist for 17 days,[75] the 98th Illinois moved out from Murfreesboro on the macadamized Manchester Pike as part of Wilder's spearhead for Reynolds’ division in Thomas’ corps.[76][77] and made for Hoover's Gap. The brigade showed the advantage of their speed despite the weather by reaching the gap nearly 9 miles (14 km) ahead of Thomas's main body.

Hoover's Gap

Once at the north end of the gap Wilder's orders were to attack through the gap to seize the narrow part located midway down the gap.[78] Once there he was to wait for Reynold's infantry to come up before advancing further. Intelligence had reported that Bate's brigade of Stewart's division defended the top of the gap.

Coming up the paved road at 10:00 a.m., brigade scouts surprised pickets of the 1st Kentucky Cavalry Regiment in camp outside the entrance of the gap.[79][80][note 7] After skirmishing briefly and withdrawing under pressure, the rebels were unable to reach the gap before the better-fed horses of the Lightning Brigade. The Kentuckians fell apart as a unit and, unluckily for the Confederates, failed in their cavalry mission to provide intelligence of the Union movement to their higher headquarters.[82]

The 98th Illinois lined up on the right flank as the brigade drove the 1st Kentucky through the entire 7 miles (11 km) length of Hoover's Gap.[83] The regiment and its mates reached the narrow part of the gap at 12:00 p.m. Wilder was quickly on the scene and, unlike previously thought, he found the summit unoccupied and his soldiers could see Bate's camp in the valley below 2 miles (3.2 km) to the east of Garrison Fork, about 3 miles (4.8 km) southwest of Beech Grove. Brigade scouts soon reported the remainder of the 1st Kentucky Cavalry were rapidly fleeing their position on the Garrison Fork of the Duck River just south of the gap.[84]

Despite Reynolds’ orders to fall back to his infantry, which was still 6 miles (9.7 km) away, Wilder determined at that moment to seize the entire length of the gap [84] On reaching the terminus of the gap Wilder established a defensive position to prevent the Confederates from retaking the gap. Wilder then sent word to Reynolds that he could and would hold the gap until Reynolds could bring up the infantry.[85] At the other end, the 98th Illinois and its comrades were met with artillery fire and found out that they were outnumbered four-to-one.[86][43]

Wilder dismounted his troops and prepared to hold the gap despite Reynolds’ orders to retreat.[87] Eight companies of the 98th Illinois were kept in reserve with one section of Rodmans and one section of the mountain howitzers. The other two companies of the 98th Illinois entrenched on the east side of the Manchester Pike to secure the brigade's left. The 72nd Indiana entrenched with its left across the pike from the two 98th Illinois companies with one section of the mountain howitzers. To its right, Wilder put two sections of the Rodmans on a hill in the center of the line, supported by the entrenched 123rd Illinois. On his right, he put the 17th Indiana entrenched on the hills south of the gap on the brigade's right flank, determined to hold its position..[88] Unknown to Wilder, it would be some time before Bate responded because as yet he was unaware of Wilder's presence.[86][43]

Although Bate was close to Hoover's Gap and retreating Confederate cavalry rode past his position without alerting him to the U. S. army's presence. Instead, the Kentucky troopers rode on to the divisional commander, Stewart, a further 1 mile (1.6 km) west at Fairfield (and roughly 5 miles (8.0 km) from the gap's southern entrance). At 2:00 p.m., Stewart ordered Bate to advance to Hoover's Gap.[89] Stewart also ordered Johnson's brigade to be ready to move to Bate's assistance if necessary.[90]

Bate moved towards Hoover's Gap, guided by elements of the 1st Kentucky Cavalry. Bate's direction of advance, parallel to Wilder's line of battle, with the high ground on his left.[89] Moving northeast to push back what he thought was Federal cavalry, Bate detached two of his regiments to move along lateral roads to protect his flanks, and continued toward the gap, now outnumbered by the 98th Illinois and its brigade, with only three of his five regiments (700 men).[91]As he approached Hoover's Gap, the pickets began to skirmish. Both Wilder and Bate perceived a threat to their flank. Wilder, whose line faced south, saw the Rebels advancing from his right (west) and pulled the 98th Illinois and his reserve artillery up to extend his right. Bate, who was advancing generally east, saw Wilder's men in the hills on his left front (north), and ordered an attack on Wilder's right in an attempt to prevent Wilder from further enhancing his position along the high ground overlooking Bate's advance.[92] Confederate artillerymen killed two of Lilly's men and the horses from one of the mountain howitzers. Lilly's battery returned fire effectively and forced the Confederate artillery to reposition.[81]

Starting at 3:30 p.m., Bate launched three determined, piecemeal attacks to dislodge Wilder but the heavy fire from Wilder's Spencers pushed Bate's infantry back after an hour-long engagement. The volume of fire caused Bate to believe he faced a "vastly superior force" and he thus established defensive positions.[93] Bate counterattacked throughout the late afternoon but could not dislodge the 98th Illinois and its brethren. When Wilder received orders to fall back through the gap, he refused claiming he could hold his ground.[43]

Meanwhile, Johnson's brigade arrived and now Bate and Johnson planned a final attack on Wilder.[43] Bate's brigade, supported by Johnson's brigade and some artillery, assaulted Wilder's position, but they were driven back by the concentrated fire of the Spencers, losing 146 killed and wounded (almost a quarter of his force) to Wilder's 61.[93] Due to the heavy volume of fire he received from the brigade, Bate initially thought he was outnumbered five-to-one.[92] By 7:00 p.m., Stewart ordered Johnson to relieve Bate's brigade and sent Bate to the rear to reorganize.[93]

Colonel James Connolly, commander of the 123rd Illinois, wrote:

As soon as the enemy opened on us with their artillery we dismounted and formed line of battle on a hill just at the south entrance to the "Gap," and our battery of light artillery was opened on them, a courier was dispatched to the rear to hurry up reinforcements, our horses were sent back some distance out of the way of bursting shells, our regiment was assigned to support the battery, the other three regiments were properly disposed, and not a moment too soon, for these preparations were scarcely completed when the enemy opened on us a terrific fire of shot and shell from five different points, and their masses of infantry, with flags flying, moved out of the woods on our right in splendid style; there were three or four times our number already in sight and still others came pouring out of the woods beyond. Our regiment lay on the hill side in mud and water, the rain pouring down in torrents, while each shell screamed so close to us as to make it seem that the next would tear us to pieces. Presently the enemy got near enough to us to make a charge on our battery, and on they came; our men are on their feet in an instant and a terrible fire from the "Spencers" causes the advancing regiment to reel and its colors fall to the ground, but in an instant their colors are up again and on they come, thinking to reach the battery before our guns can be reloaded, but they "reckoned without their host," they didn't know we had the "Spencers," and their charging yell was answered by another terrible volley, and another and another without cessation, until the poor regiment was literally cut to pieces, and but few men of that 20th Tennessee that attempted the charge will ever charge again. During all the rest of the fight at "Hoover's Gap" they never again attempted to take that battery. After the charge they moved four regiments around to our right and attempted to get in our rear, but they were met by two of our regiments posted in the woods, and in five minutes were driven back in the greatest disorder, with a loss of 250 killed and wounded.[94]

Further attacks by the Bates and Johnson were also repulsed and,after a long day of combat at 7:00 p.m., the brigade's morale was uplifted by the arrival of a fresh battery at the gallop, which meant the XIV Corps were close behind. A half hour later, infantry from Rousseau and Brannan's divisions arrived at the gap to secure the position against any further assaults.[95] Thomas, shook Wilder's hand and told him, "You have saved the lives of a thousand men by your gallant conduct today. I didn't expect to get to this gap for three days."[96] Rosecrans also arrived on the scene, and instead of reprimanding Wilder for disobeying orders, likewise congratulated him.[97]

The Chattanooga and Chickamauga campaign

As part of that brigade, it performed admirably in the Tullahoma[98][99] and Chickamauga campaigns. Its superior firepower[100] due to its Spencers was found to allow it to take on an enemy that outnumbered them on several occasions and triumph. Also, the rapidity of movement afforded by their mounts gave them a rapid response ability that could take and maintain the initiative from the rebels[101]This combat power prevented much larger Confederate units from crossing a bridge on the first day of Chickamauga[101][102][103] and stopped the left column of the Bragg's key breakthrough on the second day.[104][105]

1865

The regiment was mustered out on June 27, 1865, and discharged at Springfield, Illinois, on July 7, 1865.[106]

Affiliations, battle honors, detailed service, and casualties

Organizational affiliation

The 98th Illinois Volunteer Infantry Regiment was organized at Centralia, IL, and served with the following organizations:[5]

- 40th Brigade, 12th Division, Army of the Ohio

- November 1862, 2nd Brigade, 5th Division, Centre XIV Corps, Army of the Cumberland (AoC)

- January 1863, 2nd Brigade, 5th Division, XIV Corps, AoC

- June 1863, 1st Brigade, 4th Division, XIV Corps, AoC

- October 1863, Wilder's Mounted Infantry Brigade, AoC

- November 1863, 3rd Brigade, 2nd Division, Cavalry Corps, AoC

- December 1863, 2nd Brigade, 2nd Division, Cavalry Corps, AoC

- November 1864, 1st Brigade, 2nd Division, Cavalry Corps, Military Division of the Mississippii

List of battles

The official list of battles in which the regiment bore a part:[107]

Detailed service

1862

- Organized at Centralia, IL and mustered on September 3, 1862.

- Regiment ordered to Louisville, September 8, 1862, thence to Jeffersonville September 9, and to Shepherdsville September 19

- Moved to Elizabethtown, then to Frankfort and Versailles September 30-October 13

- March to Bowling Green, October 26-November 3

- Thence to Scottsboro November 4

- To Gallatin, TN November 26

- To Castillian Spring November 28

- To Bledsoe Creek December 14

- Operations against John Hunt Morgan in Kentucky December 22-Janary 2, 1863

1863

- Moved to Cave City, thence to Murfreesboro, TN, January 2–8

- Duty at Murfreesboro until February 2

- Expedition to Auburn, Liberty and Alexandria February 3–5

- Regiment mounted March 8

- Expedition to Woodbury March 3–8

- Expedition to Lebanon, Carthage and Liberty April 1–8

- Expedition to McMinville April 20–30

- Reconnaissance to the front May 6

- Armed with Spencer rifles May 31

- Liberty Gap June 4–10

- Tullahoma Campaign June 24-July 7

- Battle of Hoover's Gap June 24–26

- Occupation of Manchester June 27

- Decherd June 29

- Pelham and Elk River Bridge July 2

- Occupation of Middle Tennessee until August 16

- Passage the Cumberland Mountains and Tennessee River in Chickamauga Campaign August 16-September 8

- Friar's Island September 9

- Lee and Gordon's Mill September 11–13

- Ringgold September 11

- Leet's Train Yard September 12–13

- Pea Vine Ridge September 15

- Alexander's Bridge September 18

- Battle of Chickamauga September 19–21

- Operations against Wheeler and Roddy September 30-October 17

- Hill's Gap, Thompson's Cove, near Beersheeba, October 3

- Murfreesboro Road near McMinnville and McMinnville October 4

- Farmington October 7

- Sims' Farm near Shelbyville October 7

- Chattanooga-Ringgold Campaign November 23–27

- Raid on East Tennessee and Georgia Railroad November 24–27

- Charleston November 26

- Cleveland November 27

- March to relief of Knoxville and operations in East Tennessee November28, 1863, to January 6, 1864

- Near Loudon December 1

- Expedition to Murphey, NC, December 6–12

1864

- Operations in North Alabama January 23–29

- Florence, AL January 25

- Demonstration on Dalton, GA, February 22–27

- Tunnel Hill, Buzzard's Roost Gap and Rocky Face Ridge February 23–25

- Near Dalton February 23

- Atlanta Campaign May 1-September 8

- Battle of Resaca May 13–15

- Rome May 17–18

- Near Dallas May 24

- Operations on line of Pumpkin Vine Creek and battles about Dallas, New Hope Church and Allatoona Hills May 25-June 5

- Near Big Shanty July 9

- Operations about Marietta and against Kennesaw Mountain June 10-July 2

- Noonday Creek June 19-5

- Powder Springs, Lattimer's Mills, June 20

- Noonday Creek and assault on Kennesaw June 27

- Nickajack Creek July 2–5

- Rottenwood Creek July 4

- Chattahoochee River July 5–17

- Garrard's Raid to Covington July 22–24

- Siege of Atlanta July 22-August 25

- Garrard's Raid to South River July 27–31

- Flat Road Bridge July 28

- Kilpatrick's Raid around Atlanta August 20–22

- Operations at Chattahoochee River Bridge August 26-September 2

- Operations against Hood North Georgia and North Alabama September 1-November 3

- Near Lost Mountain October 4–7

- Near Hope Church October 5

- Dallas and Rome October 10–11

- Narrows October 11

- Near Rome October 13

- Near Summervllle October 1

- Little River, AL, October 20

- Leesburg October 1

- Ladiga, Terrapin Creek, October 28

- Moved to Nashville, thence to Louisville, November 2-1 and duty there refitting till December 26

- March Nashville, December 26-January 1 1865

1865

- March to Gravelly Springs, AL, and duty the until March 13

- Wilson's Raid to Macon, GA, March 1-April 24

- Summerville April 2

- Selma, AL April 2

- Montgomery April 12

- Columbus, GA, April 16

- To Macon April 20

- Provost duty at Macon until May 23

- Moved to Edgefield, TN and duty there until June, 1865

- Mustered out of federal service June 27

- Discharged at Springfield, IL, July 1865.

Total strength and casualties

The regiment suffered 30 enlisted men who were killed in action or who died of their wounds and 5 officers and 136 enlisted men who died of disease, for a total of 171 fatalities.[107]

Commanders

- Colonel John J. Funkhouser - Discharged due to wounds July 5, 1864.[3]

Armament/Equipment/Uniform

Armament

The 98th Illinois was an 1862, three-year regiment, that greatly increased the number of men under arms in the federal army. As with many of these volunteers, initially, there were not enough Model 1861 Springfield Rifles to go around so they were instead issued imported Austrian Rifle Muskets[note 8] Initially an infantry unit that served in the Army of Ohio, they then joined the Army of the Cumberland at the new year in1863. They reported the following on o0rdnance surveys:

- 4th Quarter 1862 Quarterly Ordnance Survey-259 Austrian Rifle Muskets, leaf and block sights,[109] quadrangular bayonet (.577 Cal), 25 Springfield Model 1855/1861 National Armory (NA)[note 9] and contract (.58 Cal.)[6][note 10]

- 1st Quarter 1863 Quarterly Ordnance Survey-649 Austrian Rifle Muskets, leaf and block sights, quadrangular socket bayonet (.577 Cal), 25 Springfield Model 1855/1861 National Armory (NA) and contract (.58 Cal.)[6][112]

During the spring of 1863, the regiment was converted to mounted infantry, and on May 31, it received Spencer rifles.[6] A handful of men received the Colt 5-shot revolver rifles. It was also issued Colt Model 1860 .44 "Army" pistols. They reported the following numbers of Spencers in the ordnance surveys:

- 2nd Quarter 1863 Quarterly Ordnance Survey-417 Spencer rifles, single-leaf folding sight, triangular socket bayonet (.52 Cal), 19 Colt Model 1860 (.44 Cal)[113]

- 3rd Quarter 1863 Quarterly Ordnance Survey-354 Spencer rifles, single-leaf folding sight, triangular socket bayonet (.52 Cal), 9 Colt 5-shot revolver rifles (.56 Cal)[6]

- 4th Quarter 1863 Quarterly Ordnance Survey-417 Spencer rifles, single-leaf folding sight, triangular socket bayonet (.52 Cal), 6 Colt Model 1860 (.44 Cal)[6][114]

- Issued weapons

-

Lorenz Rifle Model 1854

Lorenz Rifle Model 1854 -

M1862 Spencer rifle

M1862 Spencer rifle -

Colt Model 1855 revolving rifle

Colt Model 1855 revolving rifle

Uniforms

The 98th Illinois had enlisted to fight as infantry, and Wilder had the issue of mounting the brigade put to a vote. The men of the 98th Illinois voted to go with the change but were adamant that they wanted to move and fight as mounted infantry.[115] In March, they received new hats, standard Federal cavalry jackets trimmed in yellow (and a small amount of the prewar green trimmed mounted rifle version), and reinforced mounted trousers. The men promptly removed the yellow piping from the jackets and trousers, although some kept the green rifle trimming.[116] Like most of the western U.S. volunteers, an undecorated 1858 Hardee hat or black civilian slouch hat was the normal headgear.[115]

See also

References

Footnotes

- ^ The twenty-seven-year-old Funkhouser, had previously served as the A Company commander of the 26th Illinois Infantry Regiment during the ninety-day enlistment.[4]

- ^ Centralia lies roughly 60 miles (97 km)east of St. Louis.

- ^ A New York native, Wilder had relocated to Indiana and owned a foundry there.[13]

- ^ Meanwhile, Maj. Gen. Grant was not unhappy that Rosecrans was leaving his command as the rift between them continued to grow.[17]

- ^ The brigade was also sometimes known as the "Hatchet Brigade" because they received long-handled hatchets to carry instead of cavalry sabers.

- ^ The brigade’s other three regiments and the battery made contact elements of regular Rebel cavalry, but no decisive battle occurred, and both units left the town. Wilder had planned to cut off the enemy, but the Confederates retreated before the brigade could complete any encirclement.[49]

- ^ This regiment originally, as well as being their foes at Liberty 20 days before, was recruited by Lincoln's brother -in-law, Benjamin H Helm, who would soon fall to mortal wounds at Chickamauga.[81]

- ^ The Lorenz rifle was the third most widely used rifle during the American Civil War. The Union recorded purchases of 226,924. Its quality was inconsistent. Some were considered to be of the finest quality (particularly ones from the Vienna Arsenal), and were sometimes praised as being superior to the Enfield; others, especially those in later purchases from private contractors, were described as horrible in both design and condition. Lorenz rifles in the Civil War were generally used with .54 caliber cartridges designed for the Model 1841 "Mississippi" rifle. These differed from the cartridges manufactured in Austria and may have contributed to the unreliability of the weapons. Many of the rifles were bored out to .58 caliber to accommodate standard Springfield rifle ammunition.

- ^ In government records, National Armory refers to one of three United States Armory and Arsenals, the Springfield Armory, the Harpers Ferry Armory, and the Rock Island Arsenal. Rifle-muskets, muskets, and rifles were manufactured in Springfield and Harper's Ferry before the war. When the Rebels destroyed the Harpers Ferry Armory early in the American Civil War and stole the machinery for the Richmond Arsenal, the Springfield Armory was briefly the only government manufacturer of arms, until the Rock Island Arsenal was established in 1862. During this time production ramped up to unprecedented levels ever seen in American manufacturing up until that time, with only 9,601 rifles manufactured in 1860, rising to a peak of 276,200 by 1864. These advancements would not only give the Union a decisive technological advantage over the Confederacy during the war but served as a precursor to the mass production manufacturing that contributed to the post-war Second Industrial Revolution and 20th century machine manufacturing capabilities. American historian Merritt Roe Smith has drawn comparisons between the early assembly machining of the Springfield rifles and the later production of the Ford Model T, with the latter having considerably more parts, but producing a similar numbers of units in the earliest years of the 1913–1915 automobile assembly line, indirectly due to mass production manufacturing advancements pioneered by the armory 50 years earlier. [110][111]

- ^ The quarterly survey lacked reports from companies E, F, and H, so one can estimate from 150-250 further Lorenz or Springfield Rifled-muskets were carried by the regiment.[112]

Citations

- ^ Dyer (1908), p. 1088.

- ^ Dayton (1940), p. 4.

- ^ a b Reece (1900), p. 493.

- ^ Vance (1886), p. 356.

- ^ a b Dyer (1908), p. 1088; Federal Publishing Company (1908), p. 319; Reece (1900), pp. 515–517.

- ^ a b c d e f Baumann (1989), p. 187.

- ^ a b c d e f Van Der Linden (2023), p. 1.

- ^ Smith (2005), p. 360.

- ^ Martin (2011), pp. 178–182; Van Der Linden (2023), p. 1.

- ^ AHC, Buell (2025).

- ^ a b Powell & Wittenberg (2020), p. 14.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Reece (1900), p. 515.

- ^ Baumgartner (2007), p. 5.

- ^ Cozzens (1992), pp. 14–15; Van Der Linden (2023), p. 1.

- ^ U.S. War Dept., Official Records, Vol. 16/2, p. 595,Organization of the Army of the Ohio, October 8, 1862, pp. 591-596

- ^ Gordon (2001), pp. 119–22; Lamers (1999), pp. 171–82.

- ^ Gordon (2001), pp. 119–122.

- ^ Foote (1963), p. 80.

- ^ U.S. War Dept., Official Records, Vol. 20/1, p. 179Organization of the ... Army of the Cumberland, Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans, U.S. Army, Commanding, December 26, 1862-January 5, 1863, pp.174-182

- ^ Living History (2020).

- ^ Baumgartner (2007), p. 15; Duke (1906), p. 71.

- ^ a b U.S. War Dept., Official Records, Vol. 20/2, p. 305General Orders No.1- Numbering of the divisions and brigades of the center, Fourteenth Army Corps, January 6, 1863. pp.303-305

- ^ a b Harbison (2002), p. 1; Robertson et al. (1992), p. 47.

- ^ Harbison (2002), pp. 1–2.

- ^ Dyer (1908), p. 1089.

- ^ a b Harbison (2002), pp. 2–3.

- ^ U.S. War Dept., Official Records, Vol. 20/2, p. 326,Rosecrans to Halleck, 14 January 1863

- ^ U.S. War Dept., Official Records, Vol. 23/2, p. 34,Rosecrans to Stanton, 2 February 1863

- ^ U.S. War Dept., Official Records, Vol. 23/2, p. 74,Special Orders No. 44, 16 February 1863

- ^ U.S. War Dept., Official Records, Vol. 23/1, p. 457-461,Wilder Report (1st Bde, 4th Div. XIV Corps), 11 July 1863

- ^ Adj. Gen Indiana.Report, Vol. 3, p. 431–432.

- ^ Harbison (2002), pp. 6–7.

- ^ Harbison (2002), pp. 14.

- ^ Rowell (1975), p. 61.

- ^ a b Garrison, Graham, Parke Pierson, and Dana B. Shoaf (March 2003) “Lightning at Chickamauga.” America’s Civil War V.16 No.1.

- ^ Reece (1900), p. 516; Sunderland (1984), p. 24.

- ^ Baumann (1989), p. 237.

- ^ Harbison (2002), p. 15.

- ^ Harbison (2002), p. 20.

- ^ a b Harbison (2002), p. 21.

- ^ Baumann (1989), p. 224.

- ^ Jordan, Hubert (July 1997) “Colonel John Wilder’s Lightning Brigade Prevented Total Disaster.” America’s Civil War V.16 No.1, p. 44.

- ^ a b c d e Leigh, Phil (December 25, 2012) "Colonel Wilder's Lightning Brigade," The New York Times, p. 1.

- ^ Korn (1985), p. 21; Williams (1935).

- ^ Graf (2009), p. 311.

- ^ Dyer (1908), p. 1125; Reece (1900), p. 538.

- ^ a b Dyer (1908), p. 1088; Reece (1900), p. 516.

- ^ Harbison (2002), pp. 20–21.

- ^ Harbison (2002), p. 21; Sunderland (1969), p. 25.

- ^ Harbison (2002), p. 21; Reece (1900), p. 515.

- ^ U.S. War Dept., Official Records, Vol. 23/2, pp. 242, 248

- Rosecrans to Stanley, 16 April 1863, p.242

- Rosecrans to Stanley, 18 April 1863, pp.248-249 - ^ U.S. War Dept., Official Records, Vol. 23/2, pp. 268, 277–278

- Crook to Garfield, 23 April 1863, p.268

- Sturgis to Bowen, 25 April 1863, pp.277-278 - ^ Harbison (2002), pp. 21–22.

- ^ Harbison (2002), pp. 21–22; Reece (1900), p. 515; Rowell (1975), p. 61.

- ^ Harbison (2002), p. 22.

- ^ Rowell (1975), p. 72.

- ^ Harbison (2002), p. 23.

- ^ U.S. War Dept., Official Records, Vol. 23/1, p. 268 - Report of Maj. Gen. Joseph J. Reynolds, U. S. Army, commanding expedition, April 30, 1863, pp.267-270

- ^ Harbison (2002), p. 22; Rowell (1975), pp. 71–72.

- ^ a b c Harbison (2002), pp. 22–23; Reece (1900).

- ^ Bits of Blue and Gray.

- ^ Harbison (2002), p. 7.

- ^ Baumann (1989), p. 187; Reece (1900), p. 516.

- ^ Harbison (2002), p. 23; Reece (1900).

- ^ a b c Stuntz, Margaret L. (July 1997) “Lightning Strike at the Gap.” America’s Civil War, p. 56.

- ^ Harbison (2002), pp. 23–24.

- ^ a b Harbison (2002), p. 24.

- ^ Harbison (2002), pp. 24–25.

- ^ a b c Harbison (2002), p. 25.

- ^ Harbison (2002), p. 25; Rowell (1975), pp. 71–72.

- ^ Lamers (1999), pp. 269–271; Woodworth (1998), p. 17.

- ^ Esposito (1959), p. 108; Frisby (2000), p. 420.

- ^ Sunderland (1969), p. 74.

- ^ Korn (1985), p. 21; Woodworth (1998), p. 18.

- ^ Brewer (1991), p. 23; Eicher, McPherson & McPherson (2001), p. 496; Korn (1985), p. 29.

- ^ Brewer (1991), p. 23.

- ^ U.S. War Dept., Official Records, Vol. 23/1, p. 413Report No. 3, Organization of troops in Department of the Cumberland, 30 June 1863, p.413

- ^ Brewer (1991), p. 77.

- ^ a b NPS, Hoover's Gap, (2013).

- ^ Smith (2005), pp. 191–194.

- ^ a b Maurice (2016), p. 19.

- ^ Harbison (2002), pp. 32–33.

- ^ Reece (1900), p. 516.

- ^ a b Brewer (1991), p. 78.

- ^ Brewer (1991), p. 79.

- ^ a b Connolly (2012), p. 1.

- ^ Cozzens 1992, p. 18.

- ^ Brewer (1991), p. 80; Harbison (2002), p. 33; Kennedy (1998), p. 225.

- ^ a b Brewer (1991), p. 80; Harbison (2002), p. 33.

- ^ Brewer (1991), p. 80.

- ^ Brewer (1991), p. 81; Harbison (2002), p. 33.

- ^ a b Williams (1935), p. 183.

- ^ a b c Brewer (1991), p. 81; Harbison (2002), p. 33; Maurice (2016), p. 19.

- ^ Connolly (1959), p. 29.

- ^ Kennedy (1998), p. 225.

- ^ Connelly (1971), p. 126–27; Korn (1985), p. 24–26; Woodworth (1998), p. 21–24.

- ^ Cozzens (1992), p. 27; Leigh, Phil (December 25, 2012) "Colonel Wilder's Lightning Brigade," The New York Times, p. 1.

- ^ Robertson, Blue & Gray, Jan 2006, p. 46–50.

- ^ Sunderland (1969), p. 74; Sunderland (1984), p. 45; Kennedy (1998), p. 225.

- ^ Sunderland (1984), p. 26.

- ^ a b Robertson, Blue & Gray, Jun 2006, p. 46–50.

- ^ Robertson, Blue & Gray, Dec 2006, p. 41–45.

- ^ Robertson, Blue & Gray, Jun 2007, p. 44–47.

- ^ Robertson, Blue & Gray, Oct 2007, p. 46–48.

- ^ Jordan, Hubert (July 1997) “Colonel John Wilder’s Lightning Brigade Prevented Total Disaster.” America’s Civil War V.16 No.1, p. 48.

- ^ Dyer (1908), p. 1088; Reece (1900), p. 493.

- ^ a b Dyer (1908), p. 1088; Federal Publishing Company (1908), p. 319; Reece (1900), p. 493.

- ^ NPS, Chickamauga Battle Description, (2013).

- ^ Graf (2009), pp. 142–143.

- ^ Smithsonian, Civil War symposium, (2012).

- ^ NPS, Springfield Armory NHS, (2010).

- ^ a b Research Arsenal, Summary Statement of Ordnance, 31 December 1862.

- ^ Baumann (1989), p. 187; Graf (2009), p. 311.

- ^ Research Arsenal, Summary Statement of Ordnance, 31 December 1863.

- ^ a b Masters (2023).

- ^ Baumgartner (2007), pp. 63–64.

Sources

- "Don Carlos Buell, Biography, Significance, Civil War, Union General". American History Central. January 9, 2025. Retrieved July 25, 2025.

- Baumann, Ken (1989). Arming the Suckers, 1861-1865: A Compilation of Illinois Civil War Weapons. Dayton, OH: Morningside House. p. 237. ISBN 978-0-89029-529-8. OCLC 20662029.

- Baumgartner, Richard A. (2007). Blue Lightning: Wilder's Mounted Brigade in the Battle of Chickamauga (1st ed.). Huntington, WV: Blue Acorn Press. p. 389. ISBN 978-1-885033-35-2. OCLC 232639520.

- Brewer, Richard J, MAJ USA (1991). The Tullahoma Campaign: Operational Insights (PDF). U.S. Army Command and General Staff College Theses 1991 (Thesis Submission ed.). Fort Leavenworth, KS: Defense Technical Information Center. p. 199. OCLC 832046917. DTIC_ADA240085. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Connolly, James A. (1959). Angle, Paul McClelland (ed.). Three Years in the Army of the Cumberland: The Letters and Diary of Major James A. Connolly (1st ed.). University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0-527-19000-2. OCLC 906602437.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Connolly, James A. (2012). "Primary Sources: The Road to Chickamauga". www.battlefields.org. Washington, DC: American Battlefield Trust.

- Connelly, Thomas L (1971). Autumn of Glory: The Army of Tennessee 1862–1865 (PDF) (1st ed.). Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-0445-3. OCLC 1147753151.

- Cozzens, Peter (1992). This Terrible Sound: The Battle of Chickamauga (PDF) (1st ed.). Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-06594-1. OCLC 1147753151.

- Dayton, Aretas Arnold (1940). Recruitment and Conscription in Illinois During the Civil War (PDF). An abstract of a thesis (PhD, History thesis). Urbana, IL: University of Illinois. Retrieved July 23, 2025.

- Duke, Basil Wilson (1906). Morgan's Cavalry (PDF) (1st ed.). New York, NY & Washington, DC: Neale Pub. Co. p. 441. OCLC 35812648.

- Dyer, Frederick H. (1908). A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion (pdf). Des Moines, IA: Dyer Publishing Company. p. 1088. hdl:2027/mdp.39015026937642. LCCN 09005239. OCLC 1403309. Retrieved October 25, 2024.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Eddy, Thomas Mears (1865). The Patriotism of Illinois (PDF). Vol. I (1st ed.). Chicago, IL: Clark & Company. p. 642. LCCN 02012789. OCLC 85800687. Retrieved April 14, 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Eddy, Thomas Mears (1866). The Patriotism of Illinois (PDF). Vol. II (1st ed.). Chicago, IL: Clark & Company. p. 734. LCCN 02012789. OCLC 85800687. Retrieved April 14, 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Eicher, David J.; McPherson, James M.; McPherson, James Alan (2001). The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. New York City: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-1846-9. OCLC 892938160.

- Esposito, Vincent J. (1959). West Point Atlas of American Wars. New York City: Frederick A. Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8050-3391-5. OCLC 60298522. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Federal Publishing Company (1908). Military Affairs and Regimental Histories of New York, Maryland, West Virginia, And Ohio (PDF). The Union Army: A History of Military Affairs in the Loyal States, 1861–65 – Records of the Regiments in the Union army – Cyclopedia of battles – Memoirs of Commanders and Soldiers. Vol. III. Madison, WI: Federal Publishing Company. p. 319. hdl:2027/uva.x001866814. OCLC 1086145633.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Foote, Shelby (1963). Fredericksburg to Meridian. The Civil War: A Narrative. Vol. 2. New York, NY: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-74468-5. OCLC 1026467383.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Frisby, Derek W. (2000). Heidler, David S.; Heidler, Jeanne T. (eds.). Tullahoma Campaign. Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History. Vol. IV. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. –2733. ISBN 978-0-393-04758-5. OCLC 317783094.

- Garrison, Graham; Pierson, Parke & Shoaf, Dana B. (March 2003). "Lightning at Chickamauga". America's Civil War. 16 (1). Historynet LLC: 46–54. ISSN 1046-2899. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- Gordon, Leslie J. (2001). ""I Could Not Make Him Do As I Wished": The Failed Relationship of William S. Rosecrans and Grant". In Woodworth, Steven E. (ed.). Grant's Lieutenants: From Cairo to Vicksburg. Modern War Studies. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. pp. 109–128. ISBN 978-0-7006-1127-0. OCLC 316864104. Retrieved July 25, 2025.

- Graf, John F. (2009). Standard Catalog of Civil War Firearms (1st ed.). Iola, WI: Gun Digest Books. p. 255. ISBN 978-1-44022-470-6. LCCN 2008937702. OCLC 775354600.

- Hallock, Judith Lee (1991). Braxton Bragg and Confederate Defeat, Volume 2 (1st ed.). Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-585-13897-8. OCLC 1013879782.

- Harbison, Robert E, MAJ USA (2002). Wilder's Brigade in the Tullahoma and Chattanooga Campaigns of the American Civil War (PDF). U.S. Army Command and General Staff College Theses 2002 (Thesis Submission ed.). Fort Leavenworth, KS: Defense Technical Information Center. p. 122. OCLC 834239097. DTIC_ADA406434. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Jared, Grace Heminger (2008). "Story of Corporal William". Bits of Blue and Gray: An American Civil War Notebook. San Francisco, CA: Jayne McCormick. Archived from the original on May 14, 2008.

- Jordan, Hubert (July 1997). "Battle of Chickamauga: Colonel John Wilder's Lightning Brigade Prevented Total Disaster". America's Civil War. 10 (3). Historynet LLC: 44–49. ISSN 1046-2899. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- Kennedy, Frances H., ed. (1998). The Civil War Battlefield Guide (Kindle) (2nd ed.). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Co. ISBN 0-395-74012-6. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- Korn, Jerry (1985). The Fight for Chattanooga: Chickamauga to Missionary Ridge. The Civil War. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books. ISBN 978-0-8173-9185-0. OCLC 34581283.

- Lamers, William M. (1999). The Edge of Glory: A Biography of General William S. Rosecrans, U.S.A. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-2396-6. OCLC 40542924.

- Leigh, Phil (25 December 2012). "Colonel Wilder's Lightning Brigade". The New York Times.

- "History of Wilder's Brigade". www.oocities.org/wildersbrigade. Wilder's Brigade Mounted Infantry Living History Society. 30 April 2020.

- Martin, Samuel J. (2011). General Braxton Bragg, C.S.A. (Kindle) (2013 Kindle ed.). Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-5934-6. OCLC 617425048.

- Masters, Dan (April 1, 2023). "How Wilder's Brigade Got Their Lightning". Dan Masters' Civil War Chronicles. Retrieved July 19, 2025.

- Maurice, Eric (2016). "Send Forward Some Who Would Fight": How John T.Wilder and His "Lightning Brigade" of Mounted Infantry Changed Warfare. Graduate Thesis Collection. Indianapolis, IN: Butler University. p. 129. Retrieved July 19, 2025.

- McWhiney, Grady (1991). Braxton Bragg and Confederate Defeat, Volume 1 (1st ed.). Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-8173-0545-1. LCCN 91003554. OCLC 799285151.

- Powell, David A.; Wittenberg, Eric J. (2020). Tullahoma: The Forgotten Campaign That Changed the Civil War, June 23 - July 4 1863 (Kindle ed.). Havertown, PA: Savas Beatie. ISBN 978-1-61121-505-2. OCLC 1223086530.

- Reece, Jasper Newton (1900). Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Illinois (1900-1902) (PDF). Vol. V. Springfield, IL: Phillips Bros., State Printer. pp. 493–517. OCLC 1052542476. Retrieved April 4, 2020.

- "Research Arsenal". Research Arsenal. Retrieved September 12, 2023.

- "Research Arsenal". Research Arsenal. Retrieved September 12, 2023.

- Robertson, William Glenn, Dr.; Shanahan, Edward P., LTC USA; Boxberger, John I., LTC USA & Knapp, George E., MAJ USA (1992). Battle of Chickamauga, 18-20 September 1863 (PDF). Staff Ride Handbook (1st ed.). Fort Leavenworth, KS: Combat Studies Institute, US Army Command and General Staff College. p. 185. OCLC 464265609. Retrieved August 3, 2025.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Robertson, William Glenn (2010). "Bull of the Woods? James Longstreet at Chickamauga". In Woodworth, Steven E. (ed.). The Chickamauga Campaign (Kindle). Civil War Campaigns in the West (2011 Kindle ed.). Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 978-0-8093-8556-0. OCLC 649913237. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- Robertson, William Glenn (January 2006). "The Chickamauga Campaign: The Fall of Chattanooga". Blue & Gray Magazine. XXIII (136). Columbus, OH: Blue & Gray Enterprises. ISSN 0741-2207.

- Robertson, William Glenn (June 2006). "The Chickamauga Campaign: McLemore's Cove - Bragg's Lost Opportunity". Blue & Gray Magazine. XXIII (138). Columbus, OH: Blue & Gray Enterprises. ISSN 0741-2207.

- Robertson, William Glenn (December 2006). "The Chickamauga Campaign: The Armies Collide". Blue & Gray Magazine. XXIV (141). Columbus, OH: Blue & Gray Enterprises. ISSN 0741-2207.

- Robertson, William Glenn (June 2007). "The Chickamauga Campaign: The Battle of Chickamauga, Day 1". Blue & Gray Magazine. XXIV (144). Columbus, OH: Blue & Gray Enterprises. ISSN 0741-2207.

- Robertson, William Glenn (October 2007). "The Chickamauga Campaign: The Battle of Chickamauga, Day 2". Blue & Gray Magazine. XXV (146). Columbus, OH: Blue & Gray Enterprises. ISSN 0741-2207.

- Rowell, John W. (1975). Yankee Artillerymen: Through the Civil War with Eli Lilly's Indiana Battery. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 978-0-87049-171-9. OCLC 1254941.

- Smith, Derek (2005). The Gallant Dead: Union and Confederate Generals Killed in the Civil War (Kindle) (2011 Kindle ed.). Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-4872-8. OCLC 1022792759. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- Starr, Stephen Z. (1985). The War in the West, 1861-1865. The Union Cavalry in the Civil War. Vol. III (1st ed.). Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-1209-0. OCLC 769318010.

- Stuntz, Margaret L. (July 1997). "Lightning Strike at the Gap". America's Civil War. 10 (3). Historynet LLC: 50–57. ISSN 1046-2899. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- Sunderland, Glenn W. (1969). Lightning at Hoover's Gap: the Story of Wilder's Brigade (1st ed.). London, UK: Thomas Yoseloff. ISBN 0-498-06795-5. OCLC 894765669.

- Sunderland, Glenn W. (1984). Wilder's Lightning Brigade and Its Spencer Repeaters. Washington, IL: Bookworks. ISBN 99968-86-41-7. OCLC 12549273.

- Terrell, William Henry Harrison, Adjutant General (1866). Roster of Officers [incl.] Indiana Light Batteries 1861-1865 (PDF). Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Indiana. Vol. III. Indianapolis, IN: Samuel R. Douglas, State Printer. pp. 431–432. OCLC 558004259. Retrieved 2020-04-19.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Thomas, Edison H. (1985). John Hunt Morgan and His Raiders. Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-1-306-18437-3. OCLC 865156740.

- Tucker, Glenn (1961). Chickamauga: Bloody Battle in the West (Kindle) (2015 Kindle ed.). Indianapolis, IN: Bobbs-Merrill Co. ISBN 978-1-78625-115-2. OCLC 933587418. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - U.S. National Park Service. "NPS Chickamauga Battle Description". nps.gov. U.S. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2013-09-13. Retrieved September 14, 2017.

- U.S. National Park Service. "NPS Hoover's Gap Battle Description". nps.gov. U.S. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2013-09-13. Retrieved September 14, 2017.

- U.S. National Park Service. "NPS Springfield Armory National Historic Site". NPS.gov. National Park Service (US Govt). Retrieved 13 September 2010.

- U.S. War Department (1887). Operations in Kentucky, Middle and East Tennessee, North Alabama, and Southwest Virginia. Jun 10-Oct 31, 1862. – Part II - Correspondence, etc. The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Vol. XVI-XXVIII-II. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. hdl:2027/coo.31924077730228. OCLC 857196196.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - U.S. War Department (1887). Operations in Kentucky, Middle and East Tennessee, North Alabama, and Southwest Virginia. Nov. 1, 1862-Jan. 20, 1863. – Reports. The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Vol. XX-XXXII-I. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. OCLC 857196196.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - U.S. War Department (1887). Operations in Kentucky, Middle and East Tennessee, North Alabama, and Southwest Virginia. Nov. 1, 1862-Jan. 20, 1863. – Reports. The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Vol. XX-XXXII-II. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. hdl:2027/coo.31924077699696. OCLC 857196196.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - U.S. War Department (1889). Operations in Kentucky, Middle and East Tennessee, North Alabama, and Southwest Virginia. January 21 – August 10, 1863. – Reports. The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Vol. XXIII-XXXV-I. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. hdl:2027/coo.31924077699720. OCLC 857196196.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - U.S. War Department (1889). Operations in Kentucky, Middle and East Tennessee, North Alabama, and Southwest Virginia. January 21 – August 10, 1863. – Reports. The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Vol. XXIII-XXXV-II. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. hdl:2027/coo.31924077722985. OCLC 857196196.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - U.S. War Department (1899). Operations in Kentucky, Southwest Virginia, Tennessee, Mississippi, North Alabama, and North Georgia. August 11-October 19, 1863. – Part I Reports. The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Vol. XXX-XLII-I. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. OCLC 857196196.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - U.S. War Department (1899). Operations in Kentucky, Southwest Virginia, Tennessee, Mississippi, North Alabama, and North Georgia. August 11-October 19, 1863. – Part II Reports. The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Vol. XXX-XLII-II. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. OCLC 857196196.

- U.S. War Department (1899). Operations in Kentucky, Southwest Virginia, Tennessee, Mississippi, North Alabama, and North Georgia. August 11-October 19, 1863. – Part III Union Correspondence, etc. The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Vol. XXX-XLII-III. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. OCLC 857196196.

- Van Der Linden, Frank (October 9, 2023). "General Bragg's Impossible Dream: Take Kentucky". American Battlefield Trust. Retrieved July 25, 2025.

- Vance, Joseph W. (1886). Report of the adjutant general of the state of Illinois ... Containing reports for the years 1861-66. Springfield, Ill.: H.W. Rokker. p. 356. OCLC 679324399. Retrieved August 6, 2025.

- Williams, Samuel Cole (1935). "General John T. Wilder" (PDF). Indiana Magazine of History. 31 (3). Indiana University Department of History: 169–203. ISSN 0019-6673. JSTOR 27786743. Retrieved November 15, 2021.

- Woodworth, Steven E. (1998). Six Armies in Tennessee: The Chickamauga and Chattanooga Campaigns (Kindle) (2015 Kindle ed.). Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-9813-2. OCLC 50844494. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- Merritt Roe Smith (9 November 2012). Northern Weapons Manufacturing during the Civil War; keynote address of the 2012 Smithsonian Institution's Technology and the Civil War symposium. C-SPAN – via C-SPAN.