1893 Spanish general election

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

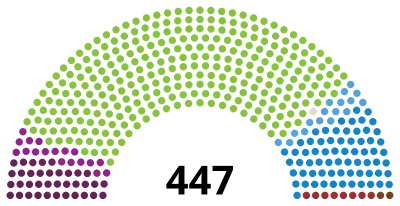

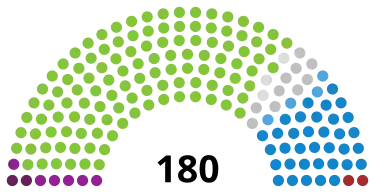

All 447 seats in the Congress of Deputies and 180 (of 360) seats in the Senate 224 seats needed for a majority in the Congress of Deputies | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Registered | 4,072,776 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Turnout | 2,786,216 (68.4%) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A general election was held in Spain on Sunday, 5 March (for the Congress of Deputies) and on Sunday, 19 March 1893 (for the Senate),[a] to elect the members of the 6th Restoration Cortes. All 442 seats in the Congress of Deputies—plus five special districts—were up for election, as well as 180 of 360 seats in the Senate.

Since the Pact of El Pardo, an informal system known as turnismo was operated by the monarchy and the country's two main parties—the Conservatives and the Liberals—to determine in advance the outcome of elections by means of electoral fraud, often achieved through the territorial clientelistic networks of local bosses (the caciques), ensuring that both parties would have rotating periods in power. As a result, elections were often neither truly free nor fair, though they could be more competitive in the country's urban centres where caciquism was weaker.

In this election, the ruling Liberal Party of Práxedes Mateo Sagasta secured a large majority in the Cortes, granting him the required parliamentary support for a new "turn" in power. This came following the downfall of Antonio Cánovas del Castillo's Conservative government in December 1892 as a result of an internal split by former minister Francisco Silvela over the issue of political regeneration. The election also saw a strong performance by pro-republican parties, which went on to win in the two main Spanish cities—Madrid and Barcelona—and secure over 10% of the seats in the Congress.

Background

The Spanish Constitution of 1876 enshrined Spain as a semi-constitutional monarchy, awarding the monarch the right of legislative initiative together with the bicameral Cortes; the capacity to veto laws passed by the legislative body; the power to appoint senators and government members (including the prime minister); as well as the title of commander-in-chief of the armed forces.[4] The monarch would play a key role in the turno system by appointing and dismissing governments, which would then organize elections to provide themselves with a parliamentary majority. This informal system allowed the two major political parties at the time, the Conservatives and the Liberals—characterized as oligarchic, elite parties with loose structures dominated by internal factions, each led by powerful individuals—to alternate in power by means of electoral fraud. This was achieved by assigning candidates to districts before the elections were held (encasillado), then arrange their victory through the links between the Ministry of Governance and the territorial clientelistic networks of provincial governors and local bosses (the caciques), excluding minor parties from the power sharing.[5][6]

The 1890–1892 government led by Antonio Cánovas del Castillo was characterized by the preservation of the political and legal reforms made by the previous Liberal government and a protectionist economic policy—seeing the approval of the "Cánovas tariff" to imports, aimed at protecting large Castilian farmers and Catalan textile manufacturers from the competition of American wheat and English fabrics.[7] The government fell apart as a result of governance minister Francisco Silvela breaking out of the Conservative Party in November 1891 over a lack of political regeneration—self-evidenced in the unveiling of administrative irregularities and corruption in the City Council of Madrid—but also because of an internal strife with long-time rival Francisco Romero Robledo, who had returned to the Conservatives' fold following the failed experience of his Liberal Reformist Party.[8][7] In addition, Cánovas' tenure had been plagued by peasant and anarchist rebellions—such as the Jerez uprising or an attempted plot to plant explosives in the Cortes parliament building—with labour conflicts, strikes and protests being commonplace.[9] The government's repression of these movements was frequently regarded as disproportionately severe, which would in turn lead to an increase in anarchist violence throughout the 1890s.[10]

Following Cánovas' resignation in December 1892, Práxedes Mateo Sagasta of the Liberal Party was tasked by Queen Regent Maria Christina with forming a new government and holding a snap election. Shortly before the election, Sagasta's government passed several decrees softening the requisites for being eligible to vote in the overseas territories of Cuba and Puerto Rico, as well as a reorganization of the electoral districts in the latter that saw the creation of several multi-member constituencies.[11][12][13]

Overview

Electoral system

The Spanish Cortes were envisaged as "co-legislative bodies", based on a nearly perfect bicameral system.[14] Both the Congress of Deputies and the Senate had legislative, control and budgetary functions, sharing equal powers except for laws on contributions or public credit, the first reading of which corresponded to Congress, and impeachment processes against government ministers, in which each chamber had separate powers of indictment (Congress) and trial (Senate).[15][16] Voting for each chamber of the Cortes was on the basis of universal manhood suffrage and censitary suffrage, respectively:

- For the Congress, it comprised all national males over 25 years of age, having at least a two-year residency in a municipality and in full enjoyment of their civil rights.[17][18][19] In Cuba and Puerto Rico, voting was on the basis of censitary suffrage, comprising males of age fulfilling one of the following criteria: being taxpayers with a minimum quota of $5 in Cuba and $10 in Puerto Rico—following a 1892 reform—per territorial contribution or per industrial or trade subsidy (paid by the time of registering for voting); having a particular position (full academics in the royal academies; members of ecclesiastical councils, including parish priests; active public employees with a yearly salary of at least $100; unemployed and retired public employees; general officers of the Army and Navy exempt from service, and retired military and naval chiefs and officers; and reporters, chamber secretaries and court clerks of higher courts); painters and sculptors awarded in national or international exhibitions; or those meeting the two-year residency requirement, provided that an educational or professional capacity could be proven.[11][20][21]

- Voters were required to not being sentenced—by a final court ruling—to perpetual disqualification from political rights or public offices, to afflictive penalties not legally rehabilitated at least two years in advance, nor to other criminal penalties that remained unserved at the time of the election; neither being legally incapacitated, bankrupt, insolvent, debtors of public funds, nor homeless.[17][20]

- For the Senate, it comprised archbishops and bishops (in the ecclesiastical councils); full academics (in the royal academies); rectors, full professors, enrolled doctors, directors of secondary education institutes and heads of special schools in their respective territories (in the universities); members with at least a three-year-old membership (in the economic societies of Friends of the Country); major taxpayers and Spanish citizens of age, being householders residing in Spain and in full enjoyment of their political and civil rights (for delegates in the local councils); and provincial deputies.[22]

The Congress of Deputies was entitled to one member per each 50,000 inhabitants, distributed among the provinces of Spain.[23][24] 116 seats were distributed among 34 multi-member constituencies and elected using a partial block voting system: in constituencies electing eight seats or more, electors could vote for no more than three candidates less than the number of seats to be allocated; in those with more than four seats and up to eight, for no more than two less; and in those with more than one seat and up to four, for no more than one less.[25] The remaining seats—326 for the 1893 election—were allocated to single-member districts and elected using plurality voting.[26][27] Additionally, literary universities, economic societies of Friends of the Country and officially organized chambers of commerce, industry and agriculture were entitled to one seat per each 5,000 registered voters that they comprised, which resulted in five additional special districts.[28]

As a result of the aforementioned allocation, each Congress multi-member constituency was entitled the following seats:[11][26][29][30]

| Seats | Constituencies |

|---|---|

| 8 | Madrid |

| 6 | Havana |

| 5 | Barcelona, Palma |

| 4 | Santa Clara, Seville |

| 3 | Alicante, Almería, Badajoz, Burgos, Cádiz, Cartagena, Córdoba, Granada, Jaén, Jerez de la Frontera, La Coruña, Lugo, Málaga, Matanzas, Mayagüez(+2), Murcia, Oviedo, Pamplona, Pinar del Río, Ponce(+2), San Juan Bautista(+2), Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Santander, Santiago de Cuba, Tarragona, Valencia, Valladolid, Zaragoza |

For the Senate, 180 seats were elected using an indirect, write-in, two-round majority voting system.[31][32] Voters in the economic societies, the local councils and major taxpayers elected delegates—equivalent in number to one per each 50 members (in each economic society) or to one-sixth of the councillors (in each local council), with an initial minimum of one—who, together with other voting-able electors, would in turn vote for senators.[33] The provinces of Álava, Albacete, Ávila, Biscay, Cuenca, Guadalajara, Guipúzcoa, Huelva, Logroño, Matanzas, Palencia, Pinar del Río, Puerto Príncipe, Santa Clara, Santander, Santiago de Cuba, Segovia, Soria, Teruel, Valladolid and Zamora were allocated two seats each, whereas each of the remaining provinces was allocated three seats, for a total of 147.[34][35][36] The remaining 33 were allocated to special districts comprising a number of institutions, electing one seat each—the archdioceses of Burgos, Granada, Santiago de Compostela, Santiago de Cuba, Seville, Tarragona, Toledo, Valencia, Valladolid and Zaragoza; the six oldest royal academies (the Royal Spanish; History; Fine Arts of San Fernando; Exact, Physical and Natural Sciences; Moral and Political Sciences and Medicine); the universities of Madrid, Barcelona, Granada, Havana, Oviedo, Salamanca, Santiago, Seville, Valencia, Valladolid and Zaragoza; and the economic societies of Friends of the Country from Madrid, Barcelona, Havana–Puerto Rico, León, Seville and Valencia.[35][37]

An additional 180 seats comprised senators in their own right—the monarch's offspring and the heir apparent once coming of age; grandees of Spain with an annual income of at least 60,000 Pt (from their own real estate or from rights that enjoy the same legal consideration); captain generals of the Army and admirals of the Navy; the Patriarch of the Indies and archbishops; and the presidents of the Council of State, the Supreme Court, the Court of Auditors, the Supreme Council of War and Navy, after two years of service—as well as senators for life appointed directly by the monarch.[38]

The law provided for by-elections to fill seats vacated in both the Congress and Senate throughout the legislature's term.[39][40]

Eligibility

For the Congress, Spanish citizens of age, of secular status, in full enjoyment of their civil rights and with the legal capacity to vote could run for election, provided that they were not contractors of public works or services, within the territorial scope of their contracts; nor holders of government-appointed offices and presidents or members of provincial deputations—during their tenure of office and up to one year after their dismissal—in constituencies within the whole or part of their respective area of jurisdiction, except for government ministers and civil servants in the Central Administration.[41][42][43] A number of other positions were exempt from ineligibility, provided that no more than 40 deputies benefitted from these:[44][45]

- Civil, military and judicial positions with a permanent residence in Madrid and a yearly public salary of at least 12,500 Pt;

- The holders of a number of positions: the president, prosecutors and chamber presidents of the territorial court of Madrid; the rector and full professors of the Central University of Madrid; inspectors of engineers; and general officers of the Army and Navy based in Madrid.

For the Senate, eligibility was limited to Spanish citizens over 35 years of age and not subject to criminal prosecution, disfranchisement nor asset seizure, provided that they were entitled to be appointed as senators in their own right or belonged or had belonged to one of the following categories:[46][47]

- Those who had ever served as senators before the promulgation of the 1876 Constitution; and deputies having served in at least three different congresses or eight terms;

- The holders of a number of positions: presidents of the Senate and the Congress; government ministers; bishops; grandees of Spain not eligible as senators in their own right; and presidents and directors of the royal academies;

- Provided an annual income of at least 7,500 Pt from either their own property, salaries from jobs that cannot be lost except for legally proven cause, or from retirement, withdrawal or termination: full academics of the aforementioned corporations on the first half of the seniority scale in their corps; first-class inspectors general of the corps of civil, mining and forest engineers; and full professors with at least four years of seniority in their category and practice;

- Provided two prior years of service: Army's lieutenant generals and Navy's vice admirals; and other members and prosecutors of the Council of State, the Supreme Court, the Court of Auditors, the Supreme Council of War and Navy, and the dean of the Court of Military Orders;

- Ambassadors after two years of service and plenipotentiaries after four;

- Those with an annual income of 20,000 Pt or were taxpayers with a minimum quota of 4,000 Pt in direct contributions at least two years in advance, provided that they either belonged to the Spanish nobility, had been previously deputies, provincial deputies or mayors in provincial capitals or towns over 20,000 inhabitants.

Other causes of ineligibility for the Senate were imposed on territorial-level officers in government bodies and institutions—during their tenure of office and up to three months after their dismissal—in constituencies within the whole or part of their respective area of jurisdiction; contractors of public works or services; tax collectors and their guarantors; debtors of the State; deputies; local councillors (except those in Madrid); and provincial deputies for their respective provinces.[48]

Election date

The term of each chamber of the Cortes—the Congress and one-half of the elective part of the Senate—expired five years from the date of their previous election, unless they were dissolved earlier.[49] The previous Congress and Senate elections were held on 1 and 15 February 1891, which meant that the legislature's terms would have expired on 1 and 15 February 1896, respectively. The monarch had the prerogative to dissolve both chambers at any given time—either jointly or separately—and call a snap election.[50][51] There was no constitutional requirement for concurrent elections to the Congress and the Senate, nor for the elective part of the Senate to be renewed in its entirety except in the case that a full dissolution was agreed by the monarch. Still, there was only one case of a separate election (for the Senate in 1877) and no half-Senate elections taking place under the 1876 Constitution.

The Cortes were officially dissolved on 5 January and 4 February 1893, with the dissolution decree setting the election dates for 5 March (for the Congress) and 19 March 1893 (for the Senate) and scheduling for both chambers to reconvene on 5 April.[52][53]

Results

Congress of Deputies

| ||||

| Parties and alliances | Popular vote | Seats | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | |||

| Liberal Party (PL) | 298 | |||

| Liberal Conservative Party (PLC) | 67 | |||

| Republican Union (UR) | 36 | |||

| Possibilist Democratic Party (PDP) | 18 | |||

| Silvelist Party (PS) | 17 | |||

| Traditionalist Communion (Carlist) (CT) | 8 | |||

| Integrist Party (PI) | 2 | |||

| Independents (INDEP) | 1 | |||

| Total | 447 | |||

| Votes cast / turnout | ||||

| Abstentions | ||||

| Registered voters | ||||

| Sources[54][55][56][57][58][59][60][61][62] | ||||

Senate

| ||

| Parties and alliances | Seats | |

|---|---|---|

| Liberal Party (PL) | 118 | |

| Liberal Conservative Party (PLC) | 35 | |

| Possibilist Democratic Party (PDP) | 6 | |

| Silvelist Party (PS) | 4 | |

| Republican Union (UR) | 2 | |

| Traditionalist Communion (Carlist) (CT) | 2 | |

| Independents (INDEP) | 3 | |

| Archbishops (ARCH) | 10 | |

| Total elective seats | 180 | |

| Sources[a][63][64][65][66][67][68] | ||

Maps

-

Election results by constituency (Congress)

Election results by constituency (Congress) -

Election results by constituency (Senate)

Election results by constituency (Senate)

Distribution by group

| Group | Parties and alliances | C | S | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PL | Liberal Party (PL) | 275 | 107 | 416 | ||

| Constitutional Union of Cuba (UCC) | 11 | 9 | ||||

| Unconditional Spanish Party (PIE) | 11 | 1 | ||||

| Basque Dynastics (Urquijist) (DV) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| PLC | Liberal Conservative Party (PLC) | 52 | 30 | 102 | ||

| Constitutional Union of Cuba (UCC) | 11 | 4 | ||||

| Unconditional Spanish Party (PIE) | 4 | 1 | ||||

| UR | Progressive Republican Party (PRP) | 14 | 1 | 38 | ||

| Federal Republican Party (PRF) | 9 | 1 | ||||

| Autonomist Liberal Party (PLA) | 7 | 0 | ||||

| Centralist Republican Party (PRC) | 6 | 0 | ||||

| PDP | Possibilist Democratic Party (PDP) | 19 | 6 | 25 | ||

| PS | Silvelist Party (PS) | 16 | 4 | 21 | ||

| Unconditional Spanish Party (PIE) | 1 | 0 | ||||

| CT | Traditionalist Communion (CT) | 8 | 2 | 10 | ||

| PI | Integrist Party (PI) | 2 | 0 | 2 | ||

| INDEP | Independents (INDEP) | 1 | 2 | 4 | ||

| Basque Dynastics (Urquijist) (DV) | 0 | 1 | ||||

| ARCH | Archbishops (ARCH) | 0 | 10 | 10 | ||

| Total | 447 | 180 | 627 | |||

Notes

- ^ a b c Senate elections in the provinces of Canaries and Lérida and in the overseas territory of Puerto Rico were postponed to 26 March 1893.[1][2][3]

- ^ Results for PL (100 deputies and 40 senators) and M (8 deputies and 1 senator) in the 1891 election.

- ^ Results for PLC (284 deputies and 114 senators) and PLR (17 deputies and 8 senators) in the 1891 election.

- ^ Results for PRP (12 deputies and 0 senators), PRF (5 deputies and 0 senators) and PRC (2 deputies and 0 senators) in the 1891 election.

References

- ^ "Resultado de la elección de senadores verificada ayer en la provincia de Lérida". National Library of Spain (in Spanish). El Imparcial. 30 March 1893. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- ^ "En Canarias". National Library of Spain (in Spanish). El Día. 1 April 1893. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- ^ "En Puerto Rico han sido electos senadores". National Library of Spain (in Spanish). La Época. 1 April 1893. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- ^ Constitution (1876), arts. 18, 22, 41, 44 & 51–54.

- ^ Martorell Linares 1997, pp. 139–143.

- ^ Martínez Relanzón 2017, pp. 147–148.

- ^ a b De la Santa Cinta, Joaquín (23 August 2017). "Presidentes del Consejo de Ministros durante la Regencia de María Cristina de Habsburgo-Lorena: Vuelve Antonio Cánovas del Castillo". El Correo de Pozuelo (in Spanish). Retrieved 4 May 2023.

- ^ Maestre Rosa 1973, pp. 208–212.

- ^ Yeoman 2019, pp. 53–60.

- ^ Tone 2006, p. 230.

- ^ a b c Roldán de Montaud 1999, p. 275.

- ^ Royal Decree of 27 December (I) (1892)

- ^ Royal Decree of 27 December (II) (1892)

- ^ Constitution (1876), arts. 18–19 & 41.

- ^ Constitution (1876), arts. 38, 42 & 45.

- ^ "El Senado en la historia constitucional española". Senate of Spain (in Spanish). Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- ^ a b Law of 26 June (1890), arts. 1–2.

- ^ García Muñoz 2002, pp. 106–107.

- ^ Carreras de Odriozola & Tafunell Sambola 2005, p. 1077.

- ^ a b Royal Decree of 27 December (I) (1892), tit. III, art. 12–18.

- ^ García Muñoz 2002, p. 107.

- ^ Law of 8 February (1877), arts. 1–3, 12–13 & 25.

- ^ Constitution (1876), arts. 27–28.

- ^ Royal Decree of 27 December (I) (1892), tit. I, arts. 1–4.

- ^ Law of 26 June (1890), art. 22.

- ^ a b Law of 26 June (1890), trans. prov. 1, applying Law of 28 December (1878), art. 2, applying Law of 1 January (1871), art. 1.

- ^ Decree of 1 April (1871), arts. 2–3.

- ^ Law of 26 June (1890), art. 24.

- ^ Royal Decree of 27 December (II) (1892), arts. 1–2, applying Royal Decree of 18 December (1890), art. 1.

- ^ Rules modifying constituency boundaries:

- Ley fijando la división de la provincia de Vizcaya en distritos para la elección de Diputados a Cortes y la de aquellos en secciones (PDF) (Law). Gaceta de Madrid (in Spanish). King of Spain. 21 March 1883. Retrieved 3 August 2025.

- Ley dividiendo la provincia de Guipúzcoa en distritos para la elección de Diputados a Cortes (PDF) (Law). Gaceta de Madrid (in Spanish). King of Spain. 23 June 1885. Retrieved 6 May 2023.

- Ley dividiendo el distrito electoral de Tarrasa en dos, que se denominarán de Tarrasa y de Sabadell (PDF) (Law). Gaceta de Madrid (in Spanish). Regent of the Kingdom p.p King of Spain. 18 January 1887. Retrieved 6 May 2023.

- Ley fijando la división de la provincia de Álava en distritos electorales para Diputados a Cortes (PDF) (Law). Gaceta de Madrid (in Spanish). Regent of the Kingdom p.p King of Spain. 10 July 1888. Retrieved 6 May 2023.

- ^ Constitution (1876), art. 20.

- ^ Law of 8 February (1877), arts. 21–22 & 53.

- ^ Law of 8 February (1877), arts. 1 & 30–31.

- ^ Law of 8 February (1877), art. 2.

- ^ a b Law of 9 January (1879), arts. 1–3.

- ^ "Real decreto determinando el número de Senadores que habrán de elegirse en cada una de las provincias con motivo de las próximas elecciones" (PDF). Gaceta de Madrid (in Spanish) (184). Agencia Estatal Boletín Oficial del Estado: 23. 3 July 1881.

- ^ Law of 8 February (1877), art. 1.

- ^ Constitution (1876), arts. 20–21.

- ^ Law of 8 February (1877), arts. 56–59.

- ^ Law of 26 June (1890), arts. 73–76.

- ^ Constitution (1876), arts. 29 & 31.

- ^ Law of 26 June (1890), arts. 3–5.

- ^ Royal Decree of 27 December (I) (1892), arts. 5–8.

- ^ Law of 7 March (1880), arts. 1–4.

- ^ Law of 31 July (1887).

- ^ Constitution (1876), arts. 22 & 26.

- ^ Law of 8 February (1877), art. 4.

- ^ Law of 8 February (1877), arts. 5–9.

- ^ Constitution (1876), arts. 24 & 30.

- ^ Constitution (1876), art. 32.

- ^ Law of 8 February (1877), art. 11.

- ^ Real decreto declarando disuelto el Congreso de los Diputados (PDF) (Royal Decree). Gaceta de Madrid (in Spanish). Regent of the Kingdom p.p King of Spain. 5 January 1893. Retrieved 18 August 2025.

- ^ Real decreto declarando disuelta la parte electiva del Senado, y mandando que las Cortes se reúnan en Madrid el día 5 de Abril próximo (PDF) (Royal Decree). Gaceta de Madrid (in Spanish). Regent of the Kingdom p.p King of Spain. 4 February 1893. Retrieved 18 August 2025.

- ^ López Domínguez 1976, pp. 472–507.

- ^ Armengol i Segú & Varela Ortega 2001, pp. 655–776.

- ^ "Las elecciones en provincias". National Library of Spain (in Spanish). La Época. 7 March 1893. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ^ "Los nuevos diputados". National Library of Spain (in Spanish). El Correo Español. 7 March 1893. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ^ "Las elecciones en provincias". National Library of Spain (in Spanish). El Heraldo de Madrid. 7 March 1893. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ "Diputados electos". National Library of Spain (in Spanish). La Correspondencia de España. 8 March 1893. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ^ "Diputados probables". National Library of Spain (in Spanish). El Siglo Futuro. 8 March 1893. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ "La Iberia". National Library of Spain (in Spanish). El Liberal. 8 March 1893. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ "Las elecciones. Diputados proclamados". National Library of Spain (in Spanish). El Día. 10 March 1893. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ "Elección de senadores en provincias". National Library of Spain (in Spanish). La Correspondencia de España. 20 March 1893. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ "Elección de senadores". National Library of Spain (in Spanish). El Día. 20 March 1893. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ "Los nuevos senadores". National Library of Spain (in Spanish). El Imparcial. 20 March 1893. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ "Elecciones de senadores". National Library of Spain (in Spanish). El Liberal. 20 March 1893. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ "Elección de senadores". National Library of Spain (in Spanish). La Unión Católica. 20 March 1893. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- ^ "Elección de senadores". National Library of Spain (in Spanish). El Siglo Futuro. 20 March 1893. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

Bibliography

- Ley mandando que los distritos para las elecciones de Diputados a Cortes sean los que se expresan en la división adjunta (PDF) (Law). Gaceta de Madrid (in Spanish). Regent of the Kingdom. 1 January 1871. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- Decreto mandando se verifiquen en Puerto Rico las elecciones ordinarias de Senadores y Diputados a Cortes (PDF) (Decree). Gaceta de Madrid (in Spanish). King of Spain, at the behest of the Minister of Overseas. 1 April 1871. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- Constitución de la Monarquía Española (PDF) (Constitution). Gaceta de Madrid (in Spanish). King of Spain. 30 June 1876. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- Ley electoral de Senadores (PDF) (Law). Gaceta de Madrid (in Spanish). King of Spain. 8 February 1877. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- Ley electoral de los Diputados a Cortes (PDF) (Law). Gaceta de Madrid (in Spanish). King of Spain. 28 December 1878. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- Ley dictando reglas para la elección de Senadores en las islas de Cuba y Puerto Rico (PDF) (Law). Gaceta de Madrid (in Spanish). King of Spain. 9 January 1879. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- Ley enumerando los empleos con los cuales es compatible el cargo de Diputado a Cortes (PDF) (Law). Gaceta de Madrid (in Spanish). King of Spain. 7 March 1880. Retrieved 15 August 2025.

- Ley reformando el art. 4º. de la ley de Incompatibilidades (PDF) (Law). Gaceta de Madrid (in Spanish). Regent of the Kingdom p.p King of Spain. 31 July 1887. Retrieved 15 August 2025.

- Ley electoral para Diputados a Cortes (PDF) (Law). Gaceta de Madrid (in Spanish). Regent of the Kingdom p.p King of Spain. 26 June 1890. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- Real decreto disponiendo que mientras no se publique nueva ley Electoral rija en la isla de Cuba la división en circunscripciones y distritos para la elección de Diputados a Cortes aprobada en el Congreso en la forma que se expresa (PDF) (Royal Decree). Gaceta de Madrid (in Spanish). Regent of the Kingdom p.p King of Spain, at the behest of the Minister of Overseas. 18 December 1890. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- Real decreto disponiendo la forma en que se han de verificar las elecciones de Diputados a Cortes en las islas de Cuba y Puerto Rico (PDF) (Royal Decree). Gaceta de Madrid (in Spanish). Regent of the Kingdom p.p King of Spain, at the behest of the Minister of Overseas. 27 December 1892. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- Real decreto declarando subsistente la división territorial para elecciones de Diputados a Cortes en las islas de Cuba y Puerto Rico, establecida por Real decreto de 18 de Diciembre de 1890 (PDF) (Royal Decree). Gaceta de Madrid (in Spanish). Regent of the Kingdom p.p King of Spain, at the behest of the Minister of Overseas. 27 December 1892. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- Fernández Almagro, Melchor (1943). "Las Cortes del siglo XIX y la práctica electoral". Revista de Estudios Políticos (in Spanish) (9–10): 383–419. ISSN 0048-7694. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- Maestre Rosa, Julio (1973). "Francisco Silvela y su liberalismo regeneracionista". Revista de Estudios Políticos (in Spanish) (187): 191–226. ISSN 0048-7694. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- López Domínguez, José María (1976). Elecciones y partidos políticos de Puerto Rico: 1809-1898 (PDF) (Thesis) (in Spanish). Vol. 1. Puerto Rico: Complutense University of Madrid. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- Martorell Linares, Miguel Ángel (1997). "La crisis parlamentaria de 1913-1917. La quiebra del sistema de relaciones parlamentarias de la Restauración". Revista de Estudios Políticos (in Spanish) (96). Madrid: Centro de Estudios Constitucionales: 137–161.

- Martínez Ruiz, Enrique; Maqueda Abreu, Consuelo; De Diego, Emilio (1999). Atlas histórico de España (in Spanish). Vol. 2. Bilbao: Ediciones KAL. pp. 109–120. ISBN 9788470903502.

- Roldán de Montaud, Inés (1999). "Política y elecciones en Cuba durante la restauración" (PDF). Revista de Estudios Políticos (in Spanish) (104): 245–287. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- Armengol i Segú, Josep; Varela Ortega, José (2001). El poder de la influencia: geografía del caciquismo en España (1875-1923) (in Spanish). Madrid: Marcial Pons. pp. 655–776. ISBN 9788425911521.

- García Muñoz, Montserrat (2002). "La documentación electoral y el fichero histórico de diputados". Revista General de Información y Documentación (in Spanish). 12 (1): 93–137. ISSN 1132-1873. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- Carreras de Odriozola, Albert; Tafunell Sambola, Xavier (2005) [1989]. Estadísticas históricas de España, siglos XIX-XX (PDF) (in Spanish). Vol. 1 (II ed.). Bilbao: Fundación BBVA. pp. 1072–1097. ISBN 84-96515-00-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015.

- Tone, John Lawrence (2006). "The Monster and the Assassin". War and Genocide in Cuba, 1895-1898. University of North Carolina Press. pp. 225–239. ISBN 9780807830062.

- Martínez Relanzón, Alejandro (2017). "Political Modernization in Spain Between 1876 and 1923". Annales Universitatis Mariae Curie-Skłodowska, Sectio K. 24 (1). Madrid: Maria Curie-Skłodowska University: 145–154. doi:10.17951/k.2017.24.1.145. S2CID 159328027.

- Yeoman, James Michael (2019). Print Culture and the Formation of the Anarchist Movement in Spain, 1890–1915 (PDF). Routledge. pp. 53–66. ISBN 978-1-00-071215-5.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)